“You know how good a flower smells when you have smelled death,” Stanley Greene once told Clement Saccomani, the managing director of the Noor agency Greene had co-founded in 2007. A cornerstone of contemporary photojournalism and storytelling, Greene died this morning, facing his disease as he faced his life – fighting.

Born in Brooklyn in 1949 to two actors, Stanley was a member of the Black Panthers and anti-Vietnam War activist as a teenager, and first got involved with art through painting. Turning to photography, he shot an epic project on San Francisco’s punk scene over the 1970s and 80s, naming it The Western Front.

After meeting W. Eugene Smith, Greene turned to photojournalism, first working as a temporary staff photographer for the New York Newsday and then starting to photograph for magazines. In 1986 he moved to Paris and began covering world events. By chance, in 1989, he was in Berlin as the Wall fell. He shot an image titled Kisses to All depicting a tutu-clad girl with a champagne bottle, which came to symbolise the sense of liberation at that moment.

In the early 1990s, Greene went to Southern Sudan to document the war and famine there for the French title Globe Hebdo (France). He travelled to Bhopal, India, again for Globe Hebdo, to report on the aftermath of the Union Carbide gas poisoning.

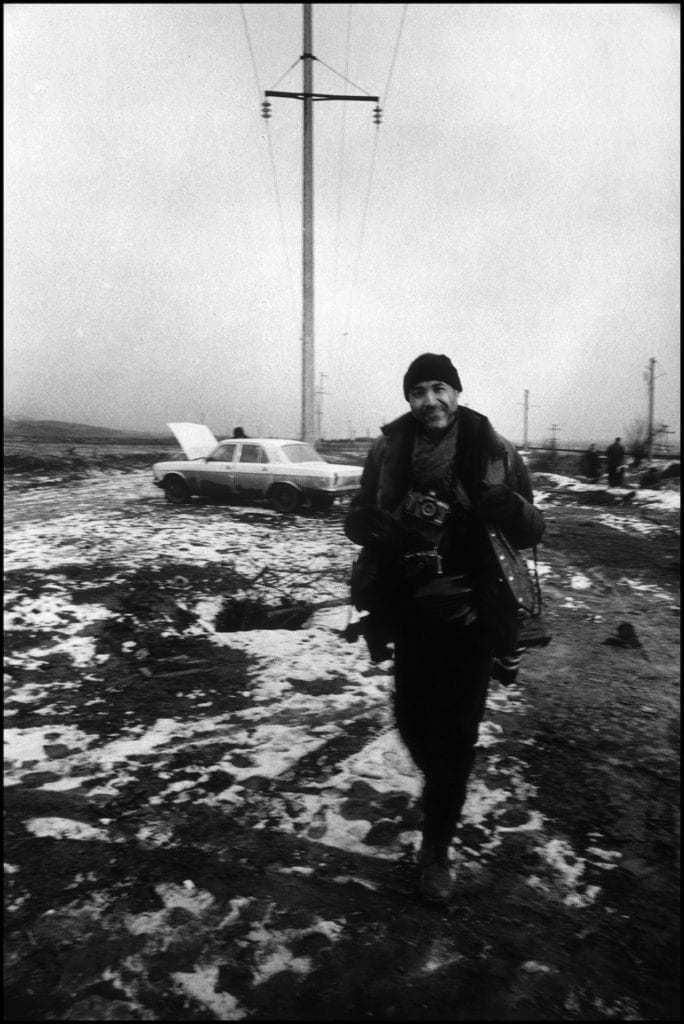

A member of the Paris-based photo agency Agence Vu from 1991 to 2007, he based himself in Moscow and worked for Liberation, Paris Match, Time, The New York Times Magazine, Newsweek, Le Nouvel Observateur, among many other international news magazines. In October 1993, he was trapped and almost killed in the Russian White House in Moscow during a coup attempt against Boris Yeltsin. He was the only Western journalist to cover the story, and two of his resulting images won World Press Photo awards.

“The first time I met him was in Perpignan – I knew his work and I bought a copy of Black Passport,” remembers Saccomani. “Two years ago he called asking if I was interested in being the agency’s new managing director. It was a great honour and of course I accepted it.

“Doing war photography was his way to resist,” Saccomani continues. “Because he truly disliked war. I think he was a believer, he had this huge faith in the future – he saw the worst of the world but defined that as a necessary pain, he told me once. He was conscious of the risks, and that his work was complicated, but he told the story that needed to be told.”

Greene received numerous awards and recognitions for his work, including the Lifetime Achievement Visa d’Or Award (2016), the Aftermath Project Grant (2013), the Prix International Planète Albert Kahn (2011), a Katrina Media Fellowship from the Open Society Institute (2006), the W. Eugene Smith Award (2004), the Alicia Patterson Fellowship (1998) and five World Press Photo awards. But for those who knew him best, his rare nature stands out as much as his work.

“Whenever you saw Stanley he would be surrounded by friends, colleagues and admirers,” says Lars Boering, managing director of World Press Photo. “It showed how popular he was – not just for his work but also for his great, unique personality. It was rare to have some time alone with him but I was lucky to have several of these moments. I loved these conversations where we discussed life, work and the world. He had a very special, stubborn, unique, funny and interesting mind of his own. We will miss him, and cherish the memories.”

“I told him a few weeks ago that my biggest regret was not to have met him earlier,” says Saccomani. “It was a privilege to meet a guy like him. He was really generous, a real, pure storyteller, a bit complicated to work with but that was his charm. He was an amazingly sweet man, who always had nice words, and we are going to miss him.”

“I remember him as one of the most classy and elegant men I ever met, a beautiful man,” Saccomani continues. “He was a great friend, a really supportive one, extremely modern and always searching for the next best picture. He was a great journalist, who always had a shot ready in advance. Almost every night he was asking me at 11 pm or midnight, ‘What’s next, what do you have in mind for the next story or the next project?’.”

https://noorimages.com/photographer/greene/