David Molina Gadea’s The Long Way Home began when he was on a year-long placement helping out at refugee centres in Belgium.

“It was a placement with the European Voluntary Service, which Britain will soon not be a part of any more because you just voted to leave the European Union,” the Spaniard tells me in a Skype interview a week after the Brexit vote.

“It lasts for one year. You go to another country in Europe, you do some work there, the EU pays for your travel and stay, and you learn the language. I went to an organisation in Belgium that arranges voluntary services and training courses, and one of the things they do is volunteer at some of the many refugee camps in Belgium. So I went there as a coordinator. We did activities and helped the staff paint the centres.”

“It was also about sharing and being with the refugees, who are from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and many other countries. It was about providing some distraction from the boredom of being there.”

Molina Gadea, who was born in 1991 near Barcelona, was placed in two centres, Rixensart near Brussels, and Sugny near the French border, where refugees who are seeking asylum feel a kind of limbo as they wait for their asylum applications to be processed.

The wait can last years. Rixensart has a lot of families and single mothers, but Sugny, which formed the bulk of images in his project, is the first port of call for newly arrived teenagers. It’s also “very male”.

“Sugny is in the middle of nowhere,” says Molina Gadea. “It’s literally in the woods. It’s on the border of Belgium and France and it helps teenagers, so it’s the first stop for young asylum seekers. They come here, they see social workers, and have a medical to determine if they really are a teenager. After a few months in Sugny, they’re sent to a better centre, a place where they can study, because in Belgium you have to study if you are a child.”

When Molina Gadea first started taking photographs at the camp, he wasn’t intending to make a project.

“For the first three days, I only photographed the walls because they were like a map,” he says. “I was living in rooms with refugees and there were these drawings on the walls – diaries of the centre. I remember one that was from Kosovo from a long time ago, and another that said, ‘I love You Irak.’ There was another that showed a simple drawing of a snake and a scorpion.

“In the context of the refugee centre, that has an immense meaning. So I’d photograph these walls and have dinner or go for a walk with the people in the camp. And then they’d get confident with me. At the end of the first week, we went out one evening to play basketball, and everyone was very excited and started asking me to take pictures. And that’s when I started photographing them.”

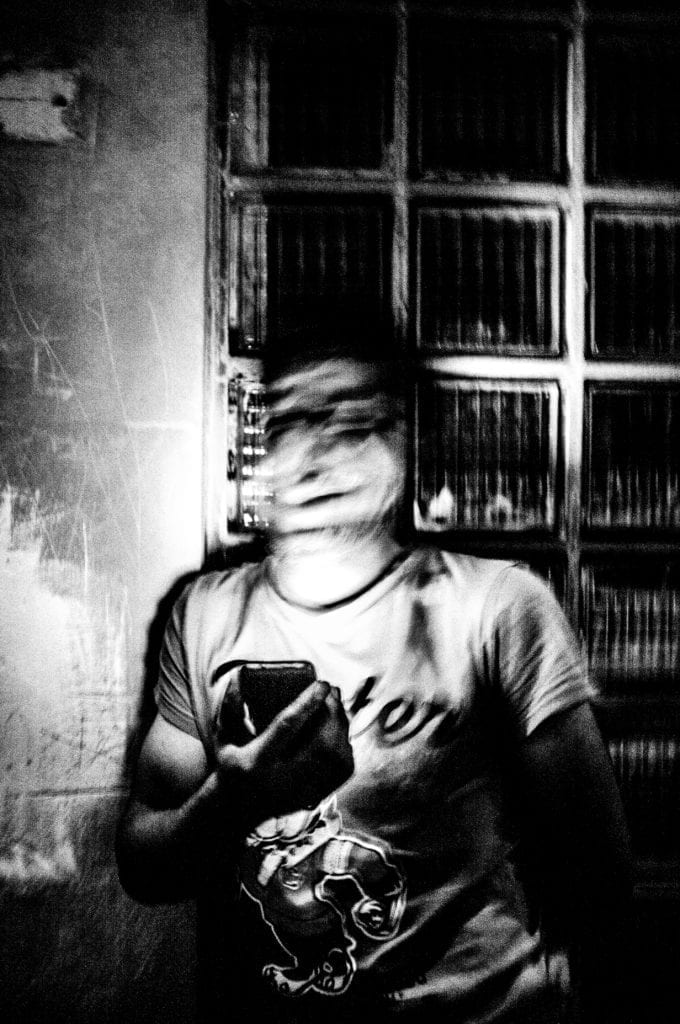

One image shows a boy with his hands raised, his mouth concealed by a flash reflected in the window. His eyes look sideways, and in the background you can see the basic layout of the camp. Another picture shows boys standing in a semi-circle on what looks like a playground. They are static: there, but not quite playing. Again, you can’t see their faces. The same effect is apparent in a picture of people standing around a fire, sparks flying, the faces barely visible, the same sense of waiting pervades. Both the anonymity and the sense of stasis are deliberate.

“People were very scared,” explains Molina Gadea. “Some people said to me, ‘You can’t show my face because I’m in danger in my country – somebody might recognise me and I don’t want them to know where I am.”

The refugees are his equals, he says, and there was no question that he would respect their wishes. “We shared rooms with them, we ate with them, we showered with them,” he says. “That’s why I didn’t make this series like a journalist – I wasn’t recording anything, I was just sharing.”

Even so, Molina Gadea was touched by the refugees’ stories – especially Immanuel’s, the boy photographed with his hands up.

“Immanuel had an amazing energy. He was in Rixensart centre as part of a big family. His father was a politician in the Central African Republic, but he was in the opposition. He was an activist and his life was in danger. Immanuel would always walk hand-in-hand with his brother Daud, going round the centre. They played with everything – with bikes, trash, they made dens. They were so playful and happy. Immanuel was eight and Daud was four.”

“But Immanuel had something different about him: he was half-adult, half-kid. In the beginning that was a shock. He was eight and he’d be talking about very harsh things, in the same way we’re talking now. Then in the next breath he’d say, ‘Let’s go and play.’ You can see sadness in their eyes, but they are not really understanding it because they have found a big family of 200 people, in a place that is full of things to do, full of places to hide.”

Molina Gadea recognises that such traumas make the refugees different to him. However, he chose not to represent these stories in favour of creating something more personal. He didn’t want to make the standard documentary report, he says, and initially was reluctant to even call his work a ‘project’.

“It didn’t begin as a project, it just began because I’m a photographer who needs to take pictures to understand the world around me,” he says. “I’m self-taught, trying to understand how to edit pictures to tell a story. I’m also trying to understand what I’m doing as a photographer.”

So it lay forgotten on the hard drive until Molina Gadea joined the 4see photo agency and was told he needed to get some work out there. “After that I entered World Press Photo and they asked me to send the raw file of one of the pictures,” he says. “That meant I was getting to the final stages of the contest, that I was up for a prize,” he believes.

“It was amazing. I was shaking. Then in the last week of the contest, they looked at the raw file and told me they could not accept my picture because it was too dark. It’s the picture of Immanuel with his hands up, which is very dark – it’s how I like to work – but it’s not acceptable according to WPP standards [which gives strict parameters on post-processing].”

All the images in the series use extreme contrast and a lot of black created in post- production, partly because that is what Molina Gadea likes, but also because he believes it communicates a message more emotionally.

“This style is about two things – what I want to say for myself, and what I want to say to others. The photography I enjoy most does this: Trent Parke, for example, and Anders Petersen, with his flash aesthetic.”

“The aesthetic is very important for me,” he continues. “Photography needs to be powerful, it needs to have something behind it. Memory works like that – the more emotional an experience, the longer it will last in your memory. And photography works like memory because if I take a picture that is strong, and is also emotionally strong, that touches you in some way, then you pay more attention and it stays with you longer.”

Despite his World Press Photo disappointment, he set about turning his collection of images into a coherent story, one that went beyond the usual representations of the ongoing European refugee crisis.

“What you usually see of refugees are people walking across borders, or people crying, but what you don’t see are pictures of what people do when they finally get to Europe,” he says. “They get really bored. For me that’s the issue. That’s the news because, depending on your age, being a refugee affects you psychologically.

“First of all, you’re stressed from your situation, then you arrive in a country where you want to work, where you might need to support people back in your country. You want to do something, but you can do nothing. There’s nowhere to go, there’s nothing to do. For me, a refugee centre is a waiting room.”

That bitter truth is reflected in his images, which focus on waiting times on the playground, by campfires, in the fields surrounding the camps, in the hallways as young refugees search for a wifi signal on their phones.

“Things like this finally came out after I finished – the diaristic nature of the walls, the boring times, the territory of somewhere like Sugny, in the middle of nowhere,” he says.

Molina Gadea has a fatalistic air when he talks about his work and the way it has to fit into a particular framework. This even extends to the fact that it has to be framed as a ‘project’, the images categorised and edited. “It became a project because everything I do now becomes a project,” he sighs.

“It became a project when I started editing the pictures. I started editing them in the centre and I thought about putting them together under a title. The title is very important – there is no project without a title. The Long Way Home puts what I was doing into context. You are talking about the trip and you are talking about what they are searching for. Without the title, there is no project.”

He also has a sense of frustration with the editing process, and the idea that there is a ‘right’ way to do it. “To be honest, I never really know how to put the pieces together,” he says.

“The edit changed many times. I sometimes wonder if there is a special secret to editing – to getting the perfect edit. I’ve asked many famous photographers to help me edit and they say, ‘Well, this photo goes with this one, and what’s the story by the way?’, and they put them in a different order and then I go home and do what I fucking want!”

For more information on the series, go here.