Photographer and anthropologist Alegra Ally accompanied the Nenets during their seasonal migration, a tradition under threat from the climate crisis

Photographer and anthropologist Alegra Ally accompanied the Nenets during their seasonal migration, a tradition under threat from the climate crisis

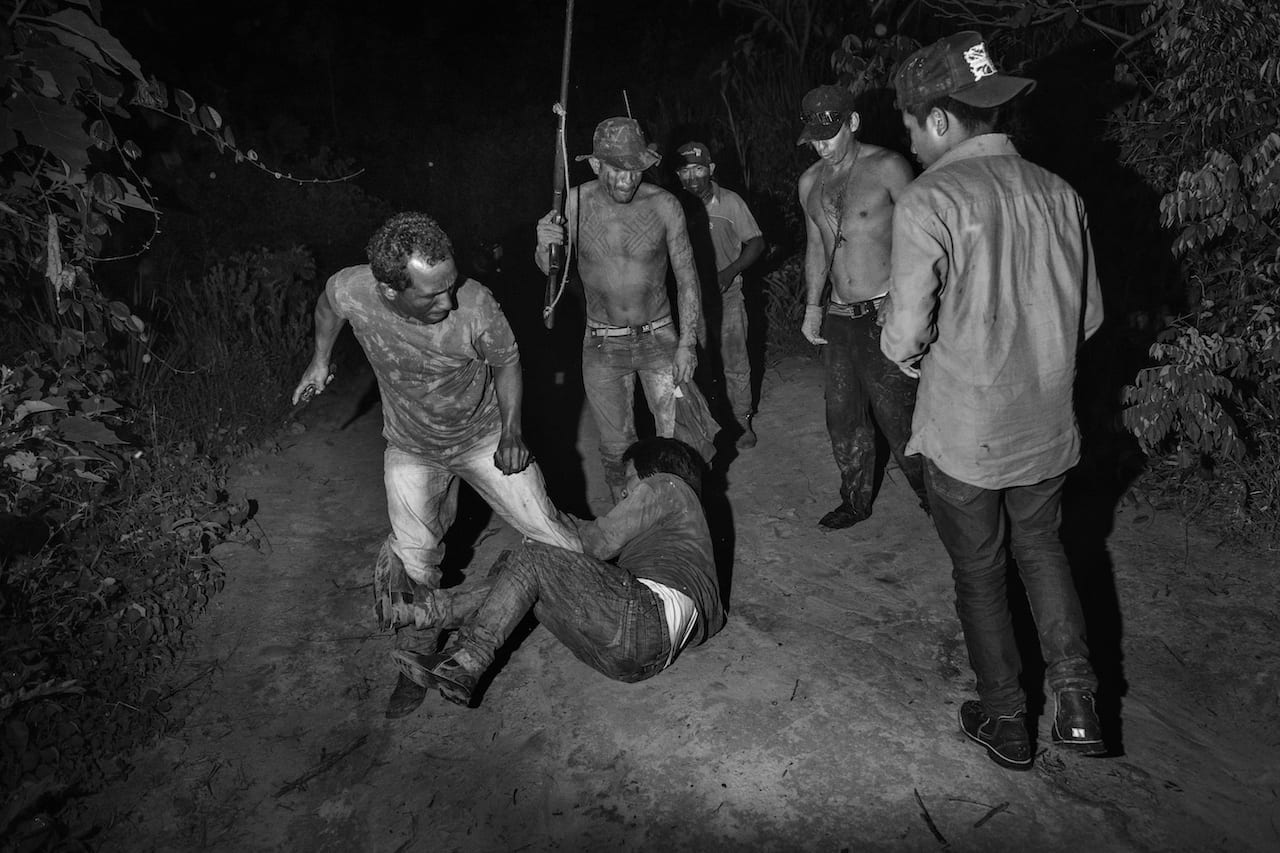

Addressing a range of issues that span deforestation, drug wars, and daily life, Tommaso Protti’s investigation into the social fabric of the Brazillian Amazon wins this year’s Carmignac Photojournalism Award

Twenty five years have passed since apartheid ended and Nelson Mandela became president. Ilvy Njiokiktjien’s decade-long project documents the opportunities and challenges faced by the children of the “rainbow nation”

“Working in Yemen is extremely difficult,” says Lorenzo Tugnoli, talking to BJP by phone from Kabul. “It’s a country where you have to navigate through various factions, and there are bureaucratic obstacles on both sides. As an example, it took us months just to get a visa.

“And even when you get access, you are not allowed to have much time. For example, after long negotiation we were allowed to go to Hodeidah, but they only let us stay for a few days. I look at my pictures in the port: I was there just for half an hour.”

Even so, Tugnoli has managed to make two extended trips to Yemen – the first for three weeks in May 2018, and the second for five weeks in November and December 2018. During those trips he travelled extensively throughout the country, crossing over the frontline and into territories held by opposing forces. Showing both the conflict and its disastrous humanitarian impact, his images have been published in a series of essays by The Washington Post, and a story pulled out of those images by Tugnoli and the director of Contrasto, Giulia Tornari, has now been nominated for the very first World Press Photo Story of the Year.

“It was a really tough story to cover, because the subject wasn’t there,” says Chris McGrath. “There was so much press there, and everyone was having the same problem – I was talking with other photographers and the Getty Images office about how to tell the story. It became every day going to the same place, standing, trying to get a picture that said something.”

The story was the disappearance of the disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi and the problem was exactly that – a Saudi Arabian journalist, author, and editor, who wrote for The Washington Post, Khashoggi had gone to the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul on 02 October 2018 and vanished. Lurid reports that he’d been killed and dismembered soon circulated, but his body has still not been found and initially, the Saudi Arabian government denied his death. There was, as McGrath says, very little to photograph.

Then on 15 October, Saudi and Turkish officials were allowed in to inspect the building, and McGrath, along with many other journalists and photographers, went along to photograph the development. “We didn’t know when the inspectors would arrive, but everyone was there,” says McGrath. “All the press was trying to get something, and this guy was holding us back.”

The Arctic circle is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, for the past five years Arctic air temperatures have exceeded all records since 1900. If temperatures continue to rise, scientists expect that the North Pole will be ice-free in summer by 2040.

Ice reflects sunlight while water absorbs it, so less ice means even higher temperatures. But the consequences of disappearing sea ice in the Arctic are more complicated than the obvious impact it has on our global climate. Less ice provides new routes for maritime shipping, and opens up new areas for the exploitation of fossil fuels, transforming the region into a strategic battleground for countries with vested interests – not to mention indigenous villages whose livelihoods are threatened by rising sea levels.

Photojournalists Yuri Kozyrev and Kadir van Lohuizen, who are both represented by NOOR, travelled through the Arctic circle, documenting the startling, and often complicated, effects of Arctic climate change. Arctic: New Frontier is the product of the ninth edition of the Carmignac Photojournalism Award, which each year funds a new investigative photo reportage on a humanitarian and geopolitical issue. An exhibition of over 50 photographs and six videos will be displayed at London’s Saatchi Gallery from 15 March until 05 May.

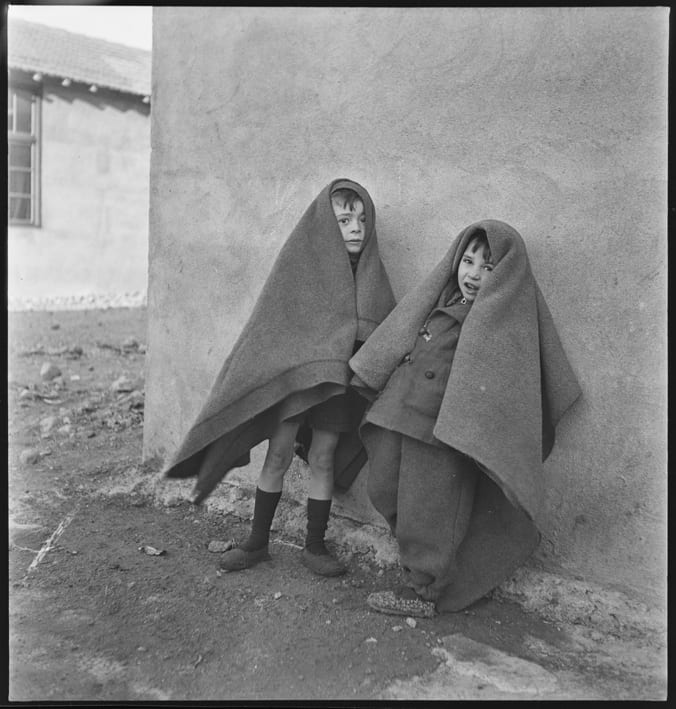

In 1939, Spanish refugees started to flee the country’s bitter civil war, in a movement that’s become known as the Retirada [the ‘withdrawal’]. More than 450,000 men, women, and children crossed the border into France in February 1939 alone, following the fall of the Second Spanish Republic and the victory of General Franco. France, anticipating the mass migration, had started to make provisions for the refugees, but underestimated the sheer numbers. Many ended up on the beaches in makeshift accommodation, and by 1940, some 50,000 had ended up in a series of camps. Diseases such as dysentery were rife, and the mortality rate high.

One of the camps was Camp de Rivesaltes, also known as Camp Maréchal Joffre. Built in 1938, near Perpignan and just 40km from the Spanish border, it had originally been intended as a military base but, following the Retirada, the French government decided to use it as an internment camp. By January 1941 was housing more than 6500 refugees though, as by then World War Two had broken out, half the camp was Spanish – the other half Jews who had fled various counties and French gypsies. In just under two years, the camp housed some 17,500 people, just over half from Spain, 40% Jewish, and 7% French gypsies.

Now in its 22nd year, the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize is awarded each year to image-makers who’ve made the biggest contribution to the medium in the previous 12 months in Europe. This year the shortlisted artists are: Laia Abril, for her publication On Abortion; Susan Meiselas, for the retrospective exhibition Mediations; Arwed Messmer, for his exhibition RAF – No Evidence / Kein Beweis; and Mark Ruwedel, for the exhibition Artist and Society: Mark Ruwedel. The winner of the £30,000 prize will be announced at The Photographers’ Gallery on 16 May 2019.

Born in Athens in 1960, Yannis Behrakis was inspired to take up photography after chancing across a Time-Life photobook as a young man. Going on to study photography in Athens and at Middlesex University in the UK, he starting work for Reuters in 1987, and by 1989 had been sent on his first foreign assignment – Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya, where he quickly made his name.

“He quickly displayed a knack for being in the right place at the right time,” reports Reuters’ site The Wider Image. “When Gaddafi visited a hotel where journalists had been cooped up for several days, a scrum of reporters crowded around the Libyan leader to get pictures and soundbites.

‘I somehow managed to sneak next to him and get some wide-angle shots,’ Behrakis wrote. ‘The next day my picture was all over the front pages of papers around the world.’”

An interview with Don McCullin is never going to be a dull affair – he is a complex man who has told the story of his life many times before. He is unfailingly polite and gentlemanly, but one detects a slightly weary tone as he goes over the familiar ground. He often pre-empts the questions with clinical self-awareness.

The story of McCullin’s rise from the impoverished backstreets of Finsbury Park in north London is one of fortuitous good luck, but it didn’t start out that way. Born in 1935, he was just 14 when his father died, after which he was brought up by his dominant, and sometimes violent, mother. During National Service with Britain’s Royal Air Force, he was posted to Suez, Kenya, Aden and Cyprus, gaining experience as a darkroom assistant. He bought a Rolleicord camera for £30 in Kenya, but pawned it when he returned home to England, and started to become a bit of a tearaway.

Redemption came when his mother redeemed the camera, and MccCullin started to take photographs of a local gang, The Guvners. One of the hoodlums killed a policeman, and McCullin was persuaded to show a group portrait of the gang to The Observer. It published the photo, and kick-started a burgeoning career as a photographer for the newspaper.