Twenty five years have passed since Nelson Mandela became president and apartheid was officially abolished. Ilvy Njiokiktjien’s decade-long project documents the opportunities and challenges faced by the children of the “rainbow nation”

Up until the early 1990s, the rights of people in South Africa were determined by the colour of their skin. Cities were segregated grids, where “Blacks” and “Coloureds” were required to carry legal documentation in “White” areas. Schools, workplaces and public toilets were also divided by race.

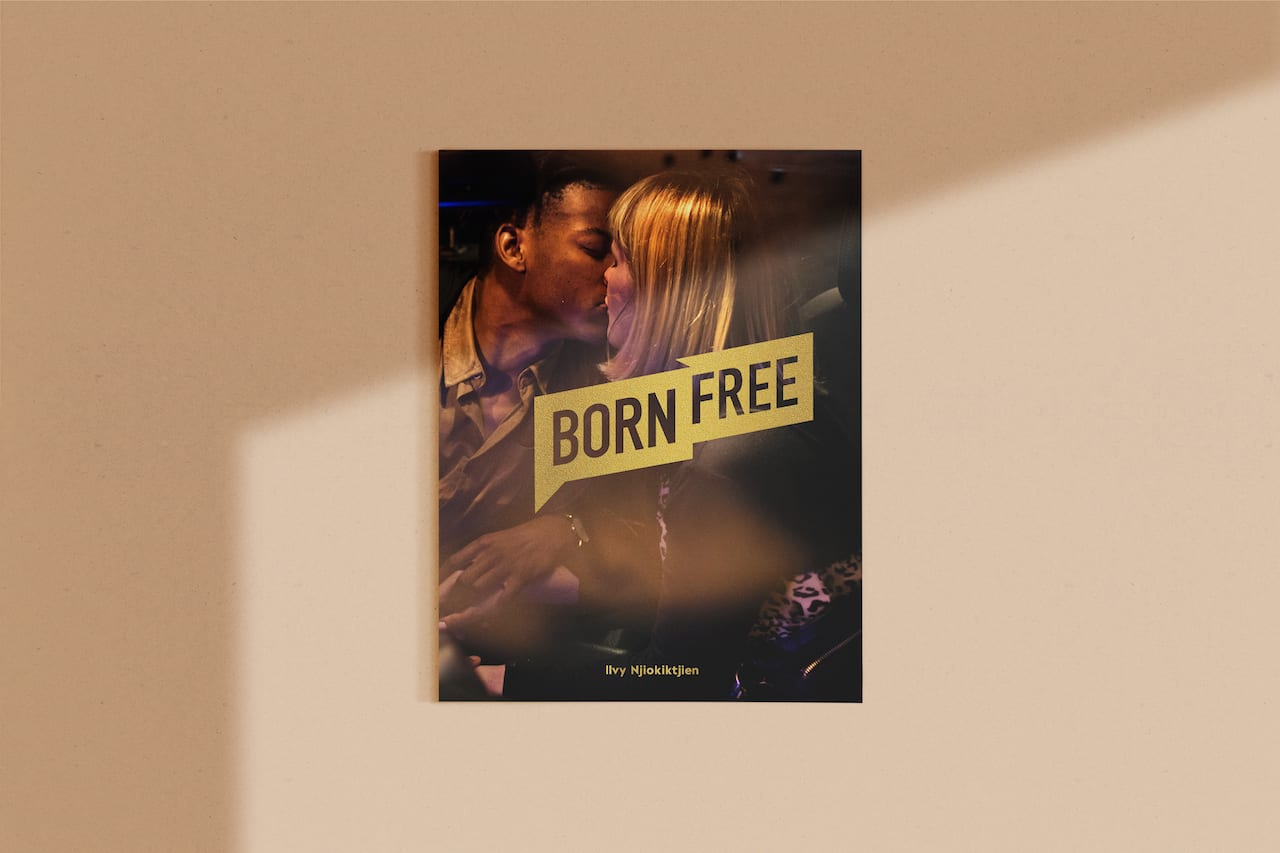

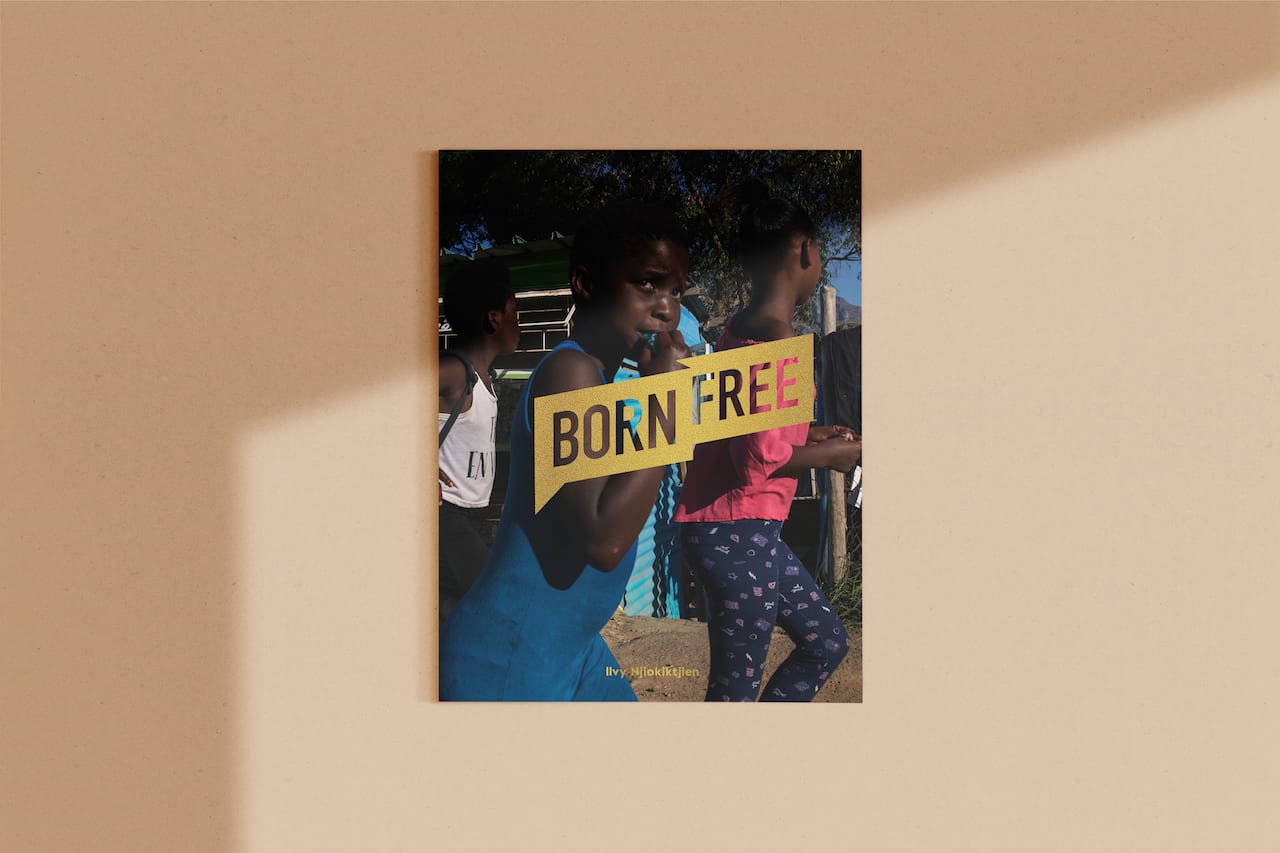

Twenty five years have passed since Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as the first black president of South Africa on 10 May 1994, and since apartheid was officially abolished. The first children born during this revolutionary period, known as the born-frees, are now coming-of-age. These young adults have been raised freely to live wherever and love whoever they wanted; they were the shining beacons of Mandela’s dreams of a “rainbow nation”.

But today, as the country votes for their sixth president since Mandela, it has become apparent that crime, poverty and corruption are still keeping many of the born-frees captive.

“Young people are disillusioned,” says photojournalist Ilvy Njiokiktjien, who has been covering South Africa for over a decade. “The atmosphere in the country is changing. When I lived there in 2004, 10 years since Mandela became president, everyone was cheerful. When I went back a few years later, I noticed the difference.”

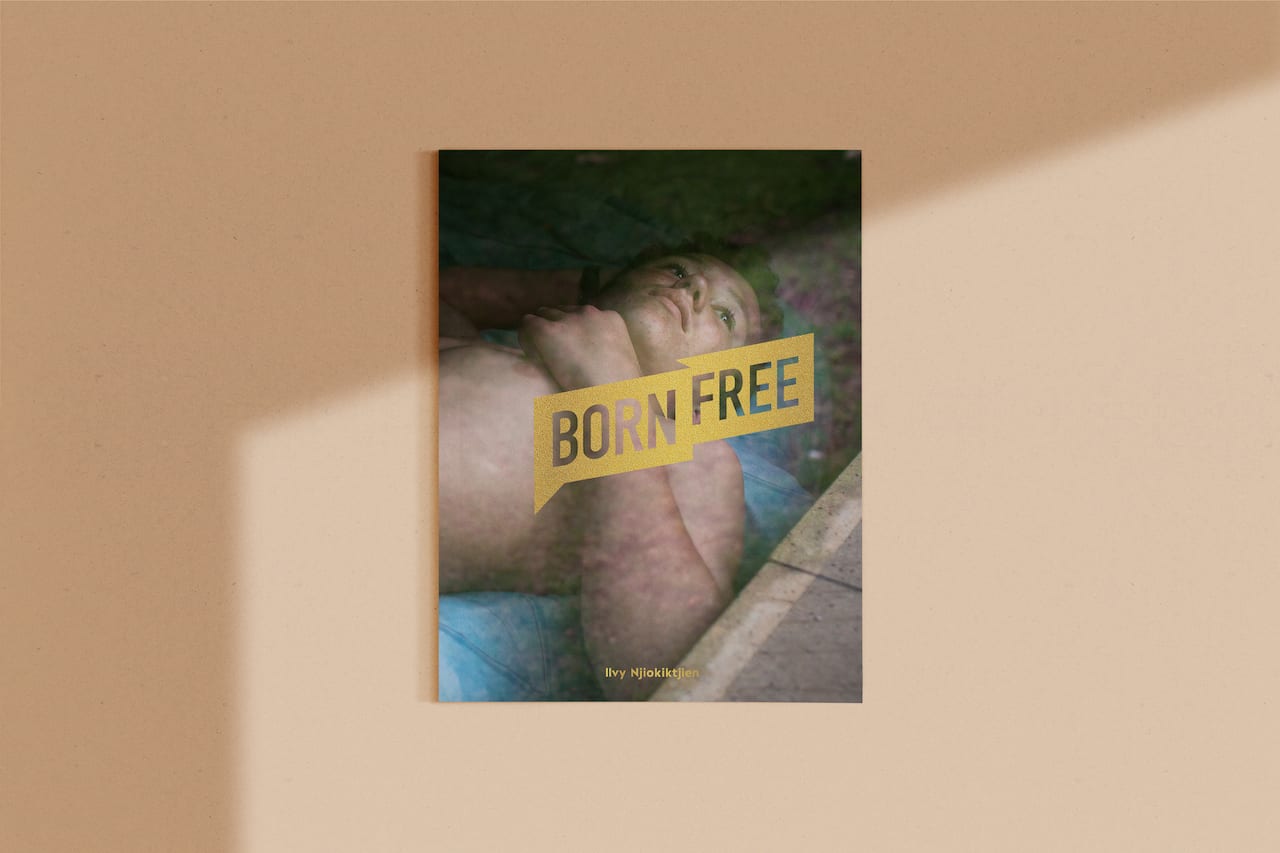

Born Free – Mandela’s Generation of Hope is Njiokiktjien’s “project of a lifetime”. Now an exhibition, photobook, an hour long documentary broadcasted on Dutch television, and a series of short films, the project combines a decade’s worth of stories about the born-free generation.

Njiokiktjien was born and raised in the Netherlands, and first went to South Africa to study in 2004. In 2007 she returned to work as an intern at South Africa’s national newspaper The Star, and later on returned to work as a freelance photographer, publishing stories for The New York Times, Der Spiegel and The Telegraph, among others. It was during this time that she became interested in youth culture, and started keeping these photographs in a separate file. “I thought one day, I’ll gather all of these photographs and make a separate project about youth.”

Over ten years, Njiokiktjien travelled to South Africa whenever she could, photographing the life of the black youth in Khayelitsha, and homelessness in Durban, where many women and children live on the street. She photographed Mandela’s funeral in 2013, followed the National Youth Orchestra on tour in Cape Town, and visited many of the previously segregated neighbourhoods. Some of the images, like her 2011 story about Kommandokorps – an extreme right-wing racist camp where teenagers are taught how to combat a perceived black enemy – were published by the press at the time, but her stories are all personally initiated.