“In my 20 years working in the industry I have never been asked if I have a degree; the only thing that really matters is the quality of your portfolio”

“In my 20 years working in the industry I have never been asked if I have a degree; the only thing that really matters is the quality of your portfolio”

Internet penetration in Kenya has grown so rapidly over the past decade that the country has been dubbed the “Silicon Savannah”. In 2009, a submarine fibre optic cable linking Mombasa to the rest of the world was launched, and construction of “Kenya Vision 2030” is now underway – a £11.2bn, 5000-acre technology city expected to create around 60,000 jobs in the IT sector.

Household tech names such as Google, Intel, Microsoft, Nokia, and Vodafone all have a presence in Kenya, and, says 27-year-old German photographer Janek Stroisch, “young entrepreneurs are seizing this opportunity as a chance to make change”. “Hundreds of youths have used the internet to launch start-up companies to try to create jobs for themselves,” he adds, “because sadly there aren’t enough to go around.”

Antonin Kratochvil has been suspended from the VII Photo Agency, pending an investigation into accusations he sexually harassed female photojournalists in the agency. The allegations were made in an article written by Kristen Chick for the Columbia Journalism Review, which contends that sexual harassment is widespread in photojournalism, and cites Kratochvil as just one example.

The report includes quotes from photographer Anastasia Taylor-Lind, a one-time member of VII, stating that Kratochvil physically groped her at a VII Annual General Meeting in Paris in 2014. “She says she was approached by founding member Antonin Kratochvil, a well-known photojournalist who has won three World Press Photo first prizes over his long career,” the article reads. “Taylor-Lind was wearing a long skirt, and said she stood with a group of people near a window during a break from the meeting.

“Without warning, Kratochvil slid his hand between her buttocks, she says, and pushed it forward until he was touching her vagina over her clothing. He held his hand there for several seconds, she says. She froze until he removed his hand and then she walked away.”

“If you live in Russia, you’re taught to love your family, and love your nation. It’s part of your life and education, we even have classes teaching patriotism at school,” says Alexander Anufriev, whose new project takes a closer look at what makes a modern Russia.

The idea for Russia Close-up came while he was studying at The Rodchenko Art School in Moscow, and starting to feel disillusioned with documentary photography. “At the time, it was important for me to tell stories and for them to be the truth, but it started to feel like a little bit of a lie,” he explains. “Even if you’re trying to be totally objective, it is always a bit subjective.

“I stopped shooting for six months, and I was about to quit photography, but then I thought, ‘What if I tried to be completely subjective?’ So I cropped the images very tightly, and included only the elements I wanted to show. It was a farewell to convention.” Unconventional it may be, but the series has already had some success, exhibited in Cardiff, Sydney, and Saint Petersburg, and winning third place in the Moscow Photobookfest Dummy book award.

Nadia Shira Cohen has won the $10,000 Women Photograph + Getty Images grant for her work on the abortion ban in El Salvador – and the five grants of $5000 awarded by Women Photograph with Nikon have gone to Tasneem Alsultan, Anna Boyiazis, Jess T. Dugan, Ana Maria Arevalo Gosen, and Etinosa Yvonne Osayimwen.

Nadia Shira Cohen’s series Yo No Di a Luz documents the effect that the complete ban on abortion in El Salvador has had on women – particularly on those forced to give birth to children conceived as a result of rape. “Doctors and nurses are trained to spy on women’s uteruses in public hospitals, reporting any suspicious alteration to the authorities and provoking criminal charges which can lead to between six months to seven years in prison,” writes Shira Cohen. “It is the poorer class of women who suffer the most as doctors in private hospitals are not required to report.

“Talking to people in Gaza, you realise how much the drones are burrowed into their daily lives,” says Daniel Tepper, an American photographer who has been researching and documenting the production and militarisation of drones in Israel since the 2014 conflict in Gaza.

In Arabic, unmanned aircrafts are referred to as ‘zenana’, local slang for the buzzing of a mosquito; in English ‘drones’ take their name from the male honeybee, and the monotonous hum it makes in flight. The Israeli military pioneered the use of drones in combat, employing the technology during the 1982 Lebanon War, and since then people in Gaza have become accustomed to the insidious noise of drones, sounding so close “they could reside beside us”, as Dr. Atef Abu Saif writes in his first-hand account of the 2014 conflict, The Drone Eats With Me. “It’s like it wants to join us for the evening and has pulled up an invisible chair,” he adds.

Despite this familiarity, what’s most scary about the drones is the fact it’s always unclear why they’re out – if they’re doing surveillance, if they’re armed, or if they’re about to strike. During the summer of 2014 the people of Gaza lived under constant surveillance, so much so you couldn’t distinguish a star or a satellite from a drone at night, says Vittoria Mentasti, an Italian photographer who experienced the conflict while reporting on it. According to Hamushim, a human rights group based in Gaza, drone warfare was responsible for almost a third of the 1543 civilian casualties in the 2014 war.

“I’ve spent so many hours on end in the dark, listening to loud music and just watching people, trying to see who I can take photos of and sussing out the environment” says Lionel Kiernan, “my work is a recording of what we can see with the naked eye in these constantly repetitive environments”.

At 21, Kiernan is the youngest photographer, and only Australian, to ever be shortlisted for the MACK First Book Award. After graduating from the Photography Studies College in Melbourne in 2017, Kiernan was nominated this year for his first major body of work documenting Melbourne’s nightlife scene, At Night.

“I was the first to move to New Brighton, and it was by sheer chance,” says Tom Wood. “I studied fine art part-time [a Fine Art Painting BA at Leicester Polytechnic], then went back to the car factory where I had worked before. Then I found a job as a photo technician at the poly [now Wirral Metropolitan College, where he went on to teach], and we moved there in September 1978.”

Thus began a golden age for photography in New Brighton, which lasted until 2003 when Wood moved to his current home in North Wales. In the intervening 25 years, Ken Grant also lived in New Brighton from 1992-2002, studying for a spell at Wirral Met, and Martin Parr was based just 20 minutes away from 1982-1985. Between them the three photographers created a huge body of work on the seaside town, which is based just across the River Mersey from Liverpool in North England.

Paul Kooiker’s latest photobook, Nude Animal Cigar, is a peculiar hybrid made up of variations on the three themes revealed in the title. It’s as if the weirdest and most beautiful nudes, mournful animals and mysterious still lifes of cigar butts have been picked out from photography’s 176- year history. But although the images look old- fashioned, they have all been made within the past five years by this contemporary Dutch artist. Applying sepia filters to all the images, he lends the series a vintage and melancholy feel, and by virtue of the treatment knits this motley trio of monochrome motifs together.

“My work is successful if it is about looking, and about photography,” says Kooiker in his studio, located in a quiet street on the southern periphery of downtown Amsterdam. “Ultimately, my work is about looking, and looking is the ultimate act of voyeurism. It makes the work accessible, as everybody is able to recognise himself in this act. It also leaves the viewer confused. What I want to achieve is to make the public feel accessory to the images they witness.”

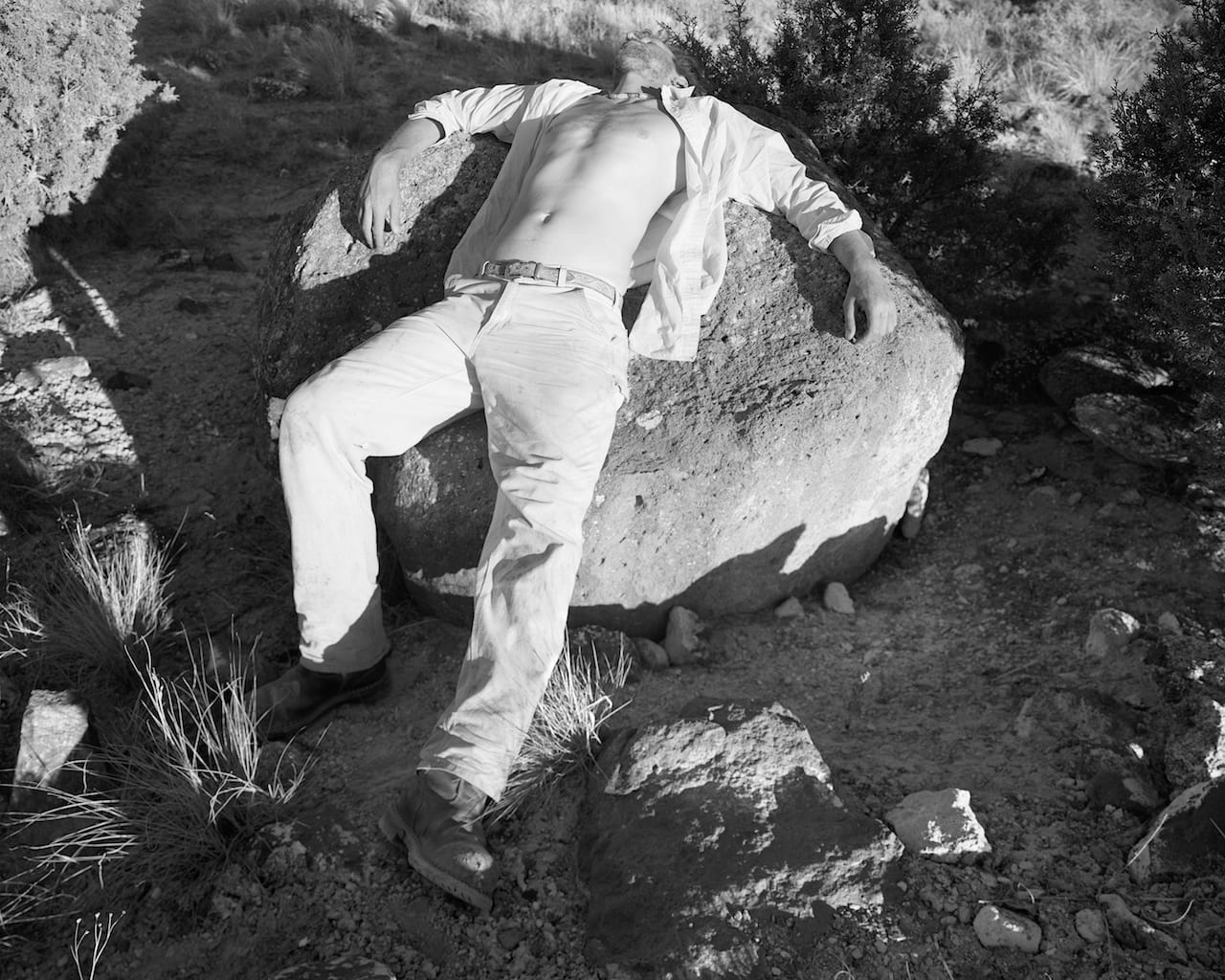

“What’s more American, iconic, and masculine than a cowboy?” asks Kristine Potter. “There is so much control within the military, so I wanted to pivot to a more lawless, unpredictable form of masculinity”.

Coming from a long line of military men on both sides of her family, Potter has long been interested in broadening the spectrum of permissible masculinity. After completing The Gray Line, a project that looks at young male cadets, she started to think about forms of masculinity other than that familiar from her youth.