All images © Diego Moreno

Mexican artist Diego Moreno has been working on Onán for the last 15 years, making photographs of his lovers, sometimes combining them with Catholic imagery

The body of Christ has accompanied Diego Moreno since birth. Growing up in Mexico he had a close relationship with the icon, studying its polychromatic skin and crimson blood by day and by night finding its ecstatic face fed his imagination. In Onán, Moreno’s identity and approach to the body are permeated by homoeroticism, which he says was nourished by Catholic imagery; the work is dedicated to the erotic drive that intertwines his life with Catholic aesthetics, and explores pleasure, guilt and the resurrection of his desire.

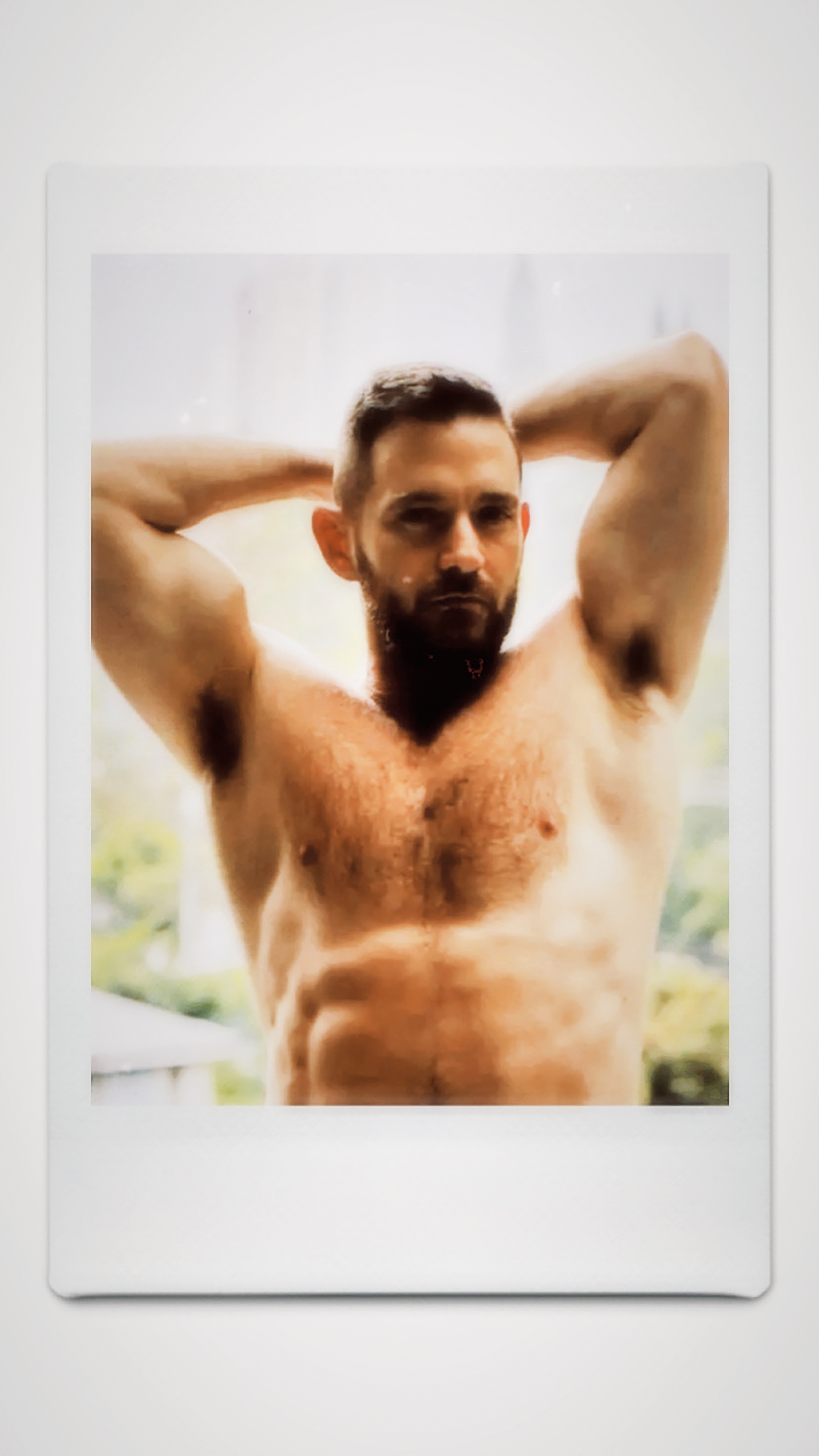

Moreno began photographing naked men in 2010 as a way to build intimacy with them, initially working in San Cristóbal de las Casas in Chiapas, a conservative society in which sin falls on difference, and where he had to secretly meet lovers in motels on the outskirts of town. Casual encounters meant an escape and, at the same time, a letter of introduction; the process of liberation was followed by a carousel of guilt. Moreno continued the project in Mexico City, and more recently in Montreux, Switzerland.

César González-Aguirre: You remember your first erotic explorations as an immersion in chaos and confusion. In this context, I can imagine the camera has been a playful tool for transforming uncertainty into a pleasurable game. What erotic roles has the camera played in this project?

Diego Moreno: I have experienced a wide range of roles and possibilities, photographing the intimate worlds of many men. Since I was a child I have been captivated by the capacity of humans to take ownership of their bodies, by changes ranging from piercings and tattoos to bodybuilding. The camera has allowed me to portray people in an intimate way, from the most basic gesture of a hug to more particular situations. Some of the men I have photographed construct characters for sexual games; they play dominant or submissive roles and use tools to inflict pleasure/pain. The camera becomes the catalyst for the most intimate, instinctive and primitive experiences.

“I have always believed in photography as an act of affection, as a route to creating deep connections with people”

CGA: Using instant photography has allowed you to establish an exchange with the men you portray, and control the circulation of the images. But the pact of trust between strangers [to take these images] is perhaps a gamble, at least in the context of a country such as Mexico. Why did you want to make Onán?

DM: I have always believed in photography as an act of affection, as a route to creating deep connections with people. These photographs are relevant to my life because they are proof of how guilt can be transformed. I grew up troubled by my sexual orientation due to religion in a conservative environment, and from an early age I was afraid of contact, of showing my emotions and the natural changes in my body. Wet dreams made me scared of being unable to control what I eventually came to accept as normal bodily processes.

My relationship with the men in my family was very painful and violent. These images take on meaning as a form of resistance, of getting to know the body through affection and desire. My photographs are proof that my relationship with men has healed over time. For years I was afraid that other men could rape me, abuse me as they did when I was a child. These photographs are evidence of the unfolding of masculinity conceived from the vulnerability of nakedness. Of living in body and soul, a story far from patriarchal violence and religious indoctrination.

CGA: While making this project, you wrote about your experiences and compiled testimonies in texts and images in a notebook. Onán began as a diary dedicated to self-confession, hidden from public gaze. Why did you decide to exhibit this personal archive?

DM: I have been working with the body for years, but I never showed this project because it caused me a lot of pain. I am someone who survived physical and sexual abuse as a child; at first I didn’t want anyone to know about that, as it revealed very intimate things about my family. But in my photobook Huésped [Hydra, 2018] and in other projects I spoke about family violence, I realised that art can help collective understanding, that these works cease to be your story and someone else can make it their own. I decided to show Onán because it becomes a testimony and a stance against the wave of phobias that minorities continue living with. It is a way of resisting and healing out loud, to prevent many others from dying in silence.

CGA: You moved to Mexico City in 2016, which allowed you to change from an identity immersed in secrecy to an exploration of the erotic. How has photography allowed you to exhume the guilt instilled by Catholicism and reclaim your body?

DM: It has been one of the main driving forces behind removing the huge web that made me unhappy for years. Photography had the power to transform my life because it helped me understand myself from the rawest place, from my body. A real body that feels and changes, that transforms and desires in ominous and unexpected ways, with its imperfect fluids and folds. Photography has been that bridge to a new paradise. Guilt is a veil that fades away every time I touch a body and envelop myself in it.

CGA: In 2021 you moved to Montreux and, because of Covid lockdowns, first connected with the city through gay dating apps. You discovered the BDSM scene, in which – as in the Catholic world – pleasure is sometimes a synonym of pain. How do the social and cultural differences between different cities manifest in the various chapters of Onán?

DM: I started taking photographs very intuitively, from a precarious position and with a lot of suspicion. I understood that not having a place to have sex was, sadly, more common than I had thought. Motels are always outside town, and you can only get to them by car. It was quite a ritual to be able to have decent, clean sex. When I moved to Mexico City, I discovered a new world, sexually speaking. Individuals had created their own meeting places; safe spaces in which it was possible to not be judged by public opinion. Over the years, the urban dynamics of cruising and sexual release, as well as online dating, have created safe and reliable places.

I moved to Switzerland and there I came to understand privilege from a sexual perspective. Each meeting place is genuinely artificial, but very well cared for, and there are strict rules of consensus, care and respect. Since I arrived in Switzerland, I have had access to PrEP [Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, used to reduce the risk of contracting HIV] and routine sexual health check-ups. There is education on LGBTQ+ issues, and all generations talk without taboo. This is a reality that remains distant from Mexico, from Chiapas.

“In Onán I paradoxically started out photographing with an instant camera; I wanted to produce unique and unrepeatable images so that, if I ever regretted taking one, I could get rid of it without leaving a trace”

CGA: In gay dating apps we can see opposite universes of anonymity and exhibitionism – in some cities, faceless user profiles reflect a conservative culture, in others profile pictures are like trophies, depicting fragments of bodies, preferably young, white and fit. Sometimes it seems like an almost fascist youth culture, in which value is placed on homogeneity and there is no place for difference. How did you play with the current uses technology allows in this project?

DM: I have focused on what I had at the time. Technically speaking, I started with digital photography – I never went into a darkroom, and I know nothing about that process.

I benefitted from the democratisation of photography, from the internet and easy access to images via cellphones. In Onán I paradoxically started out photographing with an instant camera; I wanted to produce unique and unrepeatable images so that, if I ever regretted taking one, I could get rid of it without leaving a trace. I wanted to photograph the body from a place of affection, without thinking about something technically well done. I was looking for evidence that I had been with someone else, that I had been able to build intimacy. It was a raw and easy way to preserve the memory and, at that time, a record of the change in my own body.

CGA: You began exploring your sexuality in motels on the outskirts of your hometown, San Cristóbal de las Casas; your home was a space dedicated to family and the reproduction of its values. Your identity had no place there, at least not at that point in your life. The family home and the motel are opposite spaces, the former synonymous with morality and good manners, and the latter with sin. Your project Huésped takes place within your family environment, and Onán outside of it. Are there links between the two works?

DM: The body is a trigger for desire. It can be mistreated, but it also overcomes adversity and can be a great source of affection and comfort. I photographed my maternal grandmother for more than 20 years, and I witnessed the changes in her body. I photographed her naked as a proof of the love between us, she always told me that she let me photograph her naked because she loved me. There was no other answer. The same thing happens in Onán. There are emotions that are only visible if you photograph people. In Huésped I reinterpret my family album, with all its nuances, to question family ties through the constant tension between the body and its representation. Onán brings together evidence of affection, playfulness and bonds of trust that I have with the people portrayed.

CGA: Your experiences in sex clubs and other erotic places showed you, in your own words, the primitive nature of humans and their needs. Which images have been left out of the public selection of Onán, either by your own decision or due to external factors?

DM: Photographs in which the penis is extremely exposed. But I don’t have a problem with that [exclusion], a reflection which stems from the phallocentrism which exists in the homosexual world. I think there are other, more interesting parts of the body, which are also present in the project.

CGA: You have collected religious prints and other icons for many years and, after working with your family albums in Huésped, decided to use your religious archive to reinterpret your photographs in Onán. Religious representations are collaged with the visual culture of BDSM and in this context, anonymity manifests itself in the self-censorship of those who hide their faces for moral reasons. On the other hand, there are also those who use anonymity to eroticise their bodies above their identities. What is the role of the mask in Onán?

DM: Masks are an obsession that has haunted me during my life. They are a constant symbol for understanding that your face doesn’t matter, only you matter. In BDSM practices masks are adopted as a second skin, as another possibility for transformation, and I like playing with that kind of symbolism. Masks give you the possibility to be who you want to be, even for an instant. In this project, the masks open up the possibility of identifying with the person portrayed wearing one.

CGA: Photography is always a mirror for you, a place of encounter with the other. In which photographs have you found your face, your body, when making Onán?

DM: In shadow and light. And objects and fluids are like self-portraits all the time. There is something that my gaze exerts when photographing sheets, my fluids, and my shadow in hotels. It is a genuine trace of knowing that I am there, enjoying the moment, flying over another body. Welcome to Onán, a paradise in flames.

CGA: Why did you choose Onán as the name of your project? What does this biblical character mean to you?

DM: During church visits in my adolescence, the priest emphasised that masturbation is a sin, that you must stay away from such demonic temptations. He referred to onanism as

an interruption to the act of procreation; masturbating was a perversion in which pleasure was to be punished, condemned. Years later, I had a great sexual friend named Onán, who had also had complex experiences with religion.

As a title, Onán is short and powerful. Onán is a man in a biblical passage who masturbated because he couldn’t impregnate his sister-in-law after his brother’s death. He broke the rules and was sentenced to death for rebelling. I think many of us are like him; a body and soul that public opinion condemns for disobeying the binary norms of our societies.