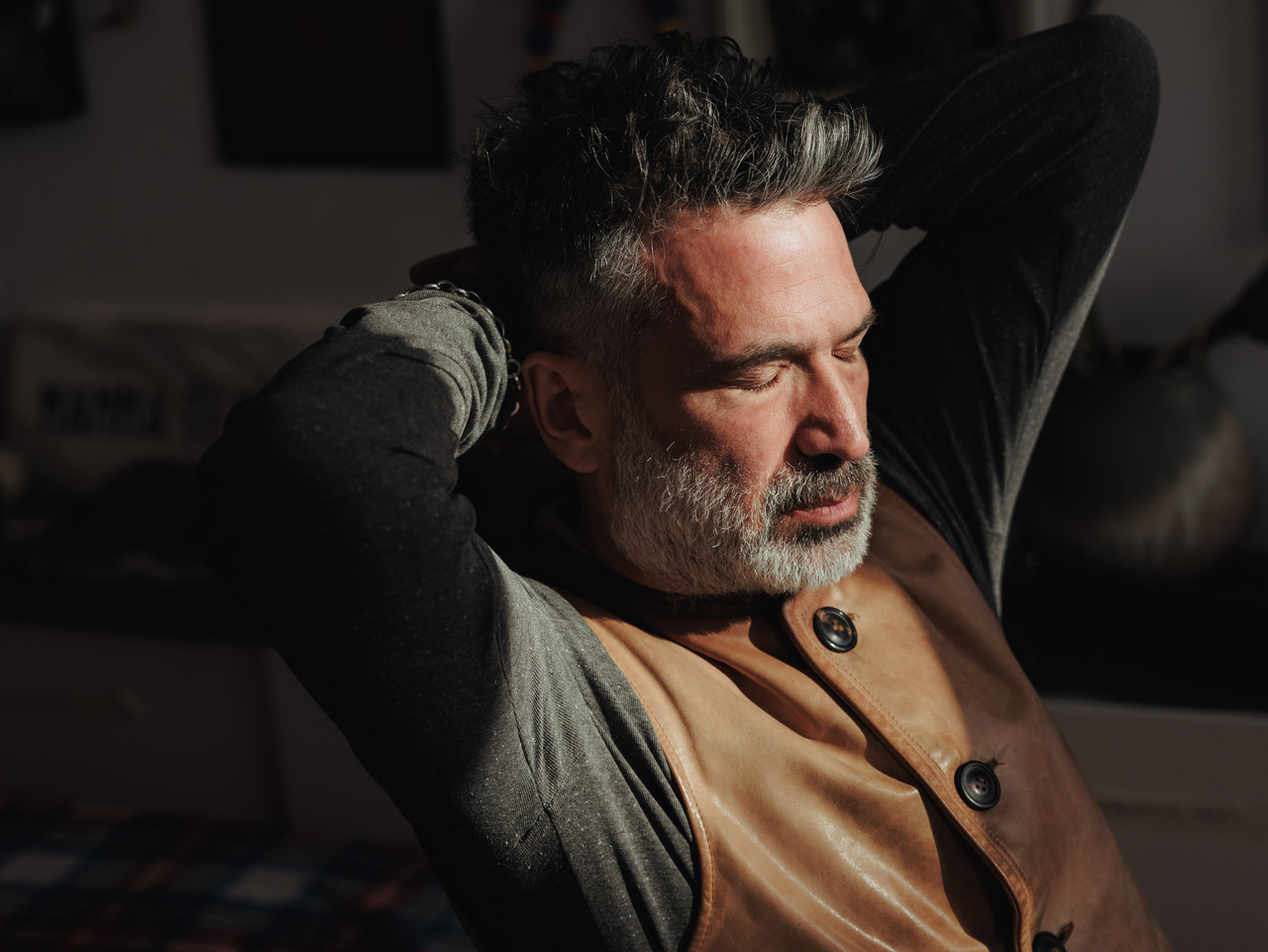

Adam Broomberg in his studio. All images © Felix Brüggemann.

Brought up in apartheid-era South Africa, Adam Broomberg’s art has always been political and remains so in the Berlin home studio in which he lives and works

In an apartment block in the Prenzlauer Berg district of Berlin, lives artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg. Formerly one half of the acclaimed duo Broomberg & Chanarin – alongside the British artist Oliver Chanarin, with whom he parted ways four years ago – Broomberg has spent his career hacking into the very source code of photography (to paraphrase the academic and founder/director of Forensic Architecture, Eyal Weizman). His work explores conflict, power and the ways in which photography intersects with the two, whether photojournalism, portraiture or footage from government surveillance cameras. Resistant to easy categorisation, his practice has taken many forms over the years, from artist books and archiving through to photomontage and performance. I am curious to see how Broomberg’s home studio reflects the ideas and methodologies that have long preoccupied him.

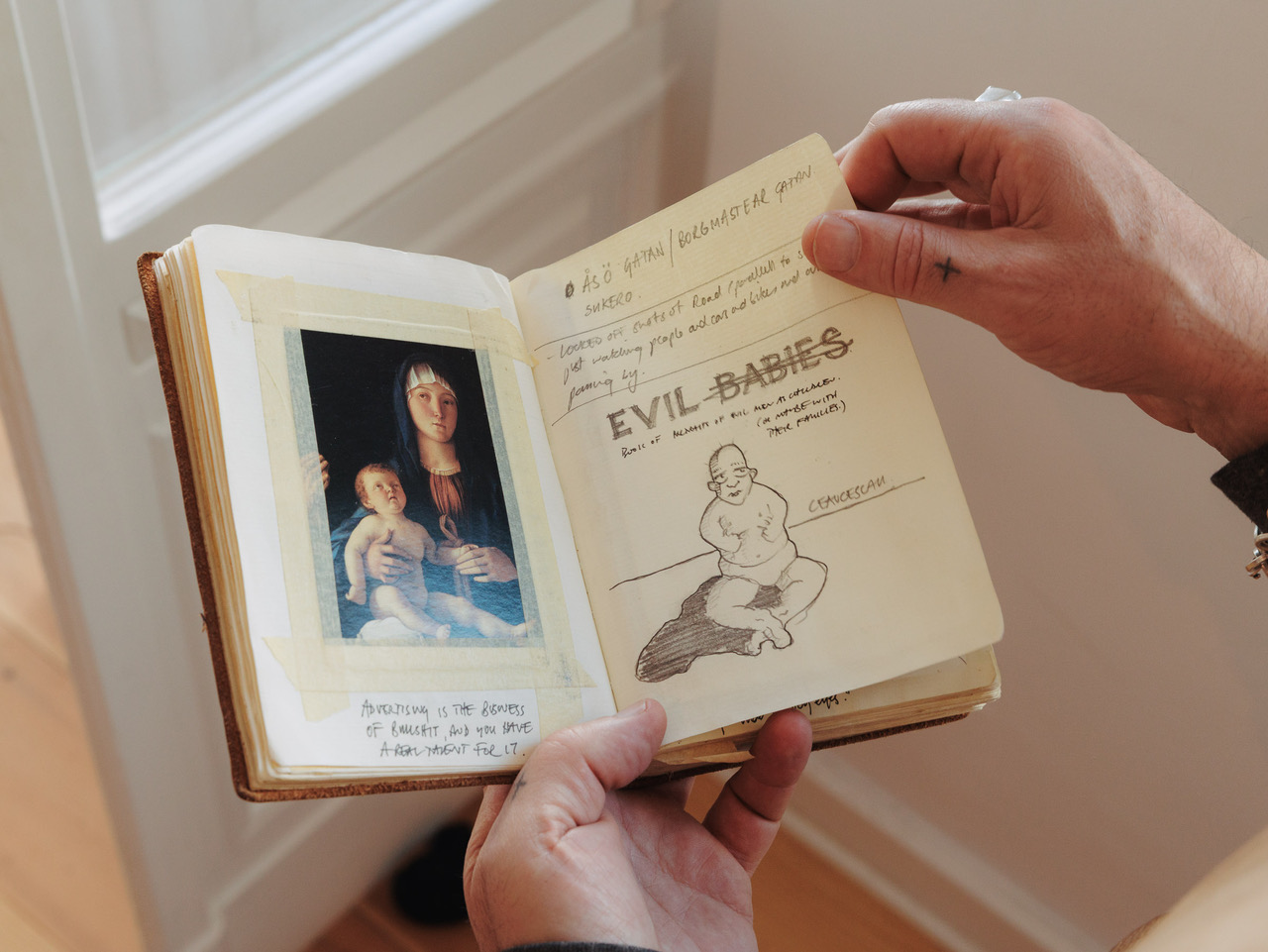

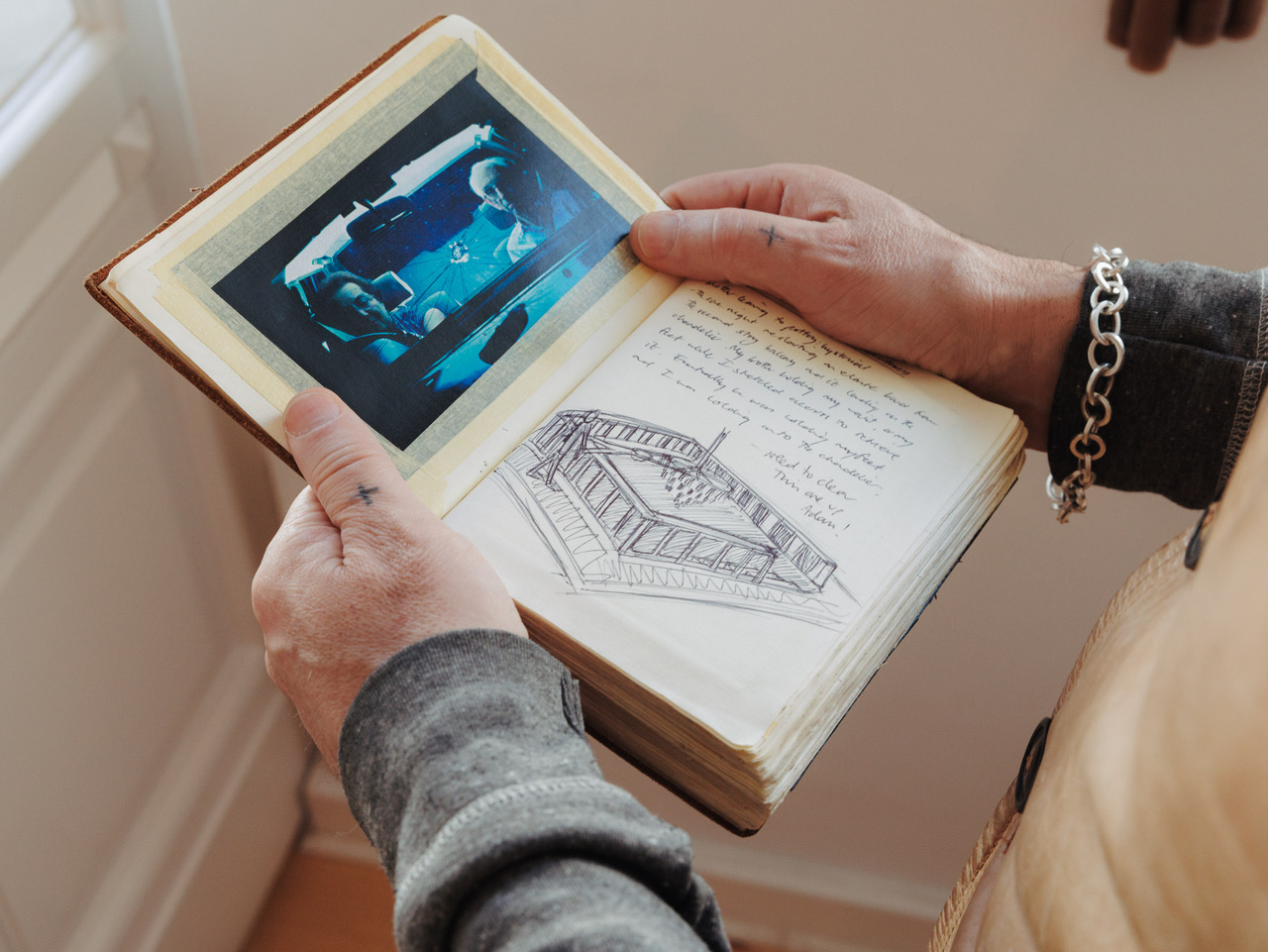

As I ascend the communal staircase, Broomberg is waiting at the front door of his apartment wearing earthy hues and a friendly smile. He is restraining a big, white, fluffy dog, who is shaking with excitement. “Sorry, he’s still a puppy,” Broomberg says as the creature leaps up, investigating my bag with the intensity of a sniffer dog. Broomberg has been working from home for the past year, abandoning his studio in favour of his living room, a quintessential Berlin wohnzimmer with wooden floorboards, white walls topped with intricate cornicing, and lots of light courtesy of a tall window and even taller balcony door. The room is comforting and characterful, strewn with an assortment of stuff – stationery, cameras, dog toys, artworks, and multiple books, including Broomberg’s own scrapbooks. “It feels good to be here,” he says. “Berlin doesn’t feel very safe to me at the moment because I’ve made myself very visible, so home feels like a hub.”

He is referring to his vocal support for Palestine, which has led to damning accusations that he – a Jewish man, whose grandparents survived the Holocaust, and who attended a Zionist school in his native South Africa – is antisemitic. In May 2023, he was arrested by German police in Berlin at a Jewish-led Nakba commemoration (marking the mass displacement of the majority of the Palestinian population in 1948); in January, he was fired from his role as a guest professor at a German art school.

“There were four or five of us who experienced the same thing, including the Mexican artist Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, whose grandparents escaped the Nazis,” he says. “These two journalists went through all our social media, took things that were seemingly ‘antisemitic’ in this German sense, and then sent them to the places we were working at, as well as to the senate. They also published an article in the right-wing press, all within a week. The institutions had to capitulate to the state – all the institutions here, including the universities, are state- funded.” It is estimated that more than 200 artists to date have had art shows or talks cancelled, funding withdrawn, or criminal charges made against them in Germany after expressing solidarity with Palestine.

Broomberg has always been political, in life and in art. He was born in 1970, at the height of apartheid in South Africa, and was active in the anti-apartheid movement from the age of 15. He left his home country in 1990 to study in London, and politics have very much informed where he has lived ever since. “After London, I went to Italy for about seven years but then Berlusconi and Lega Nord, the right wing [took over], so I moved back to London,” he says. “I was there for about 15 years, very settled, but then Brexit happened. At the same time, I got a job with Olly [Chanarin] as a professor in Hamburg, and had a show here in Berlin. At a dinner at the end of the show I said, ‘Does anyone know of a school’ – because we had two young kids – ‘and an apartment in Berlin?’ Somebody at the table knew a school, somebody else had an apartment, and a week later we arrived here with two bags – ostensibly for six months, but we’ve just stayed. Berlin felt so different to London then. But now this place…” he trails off.

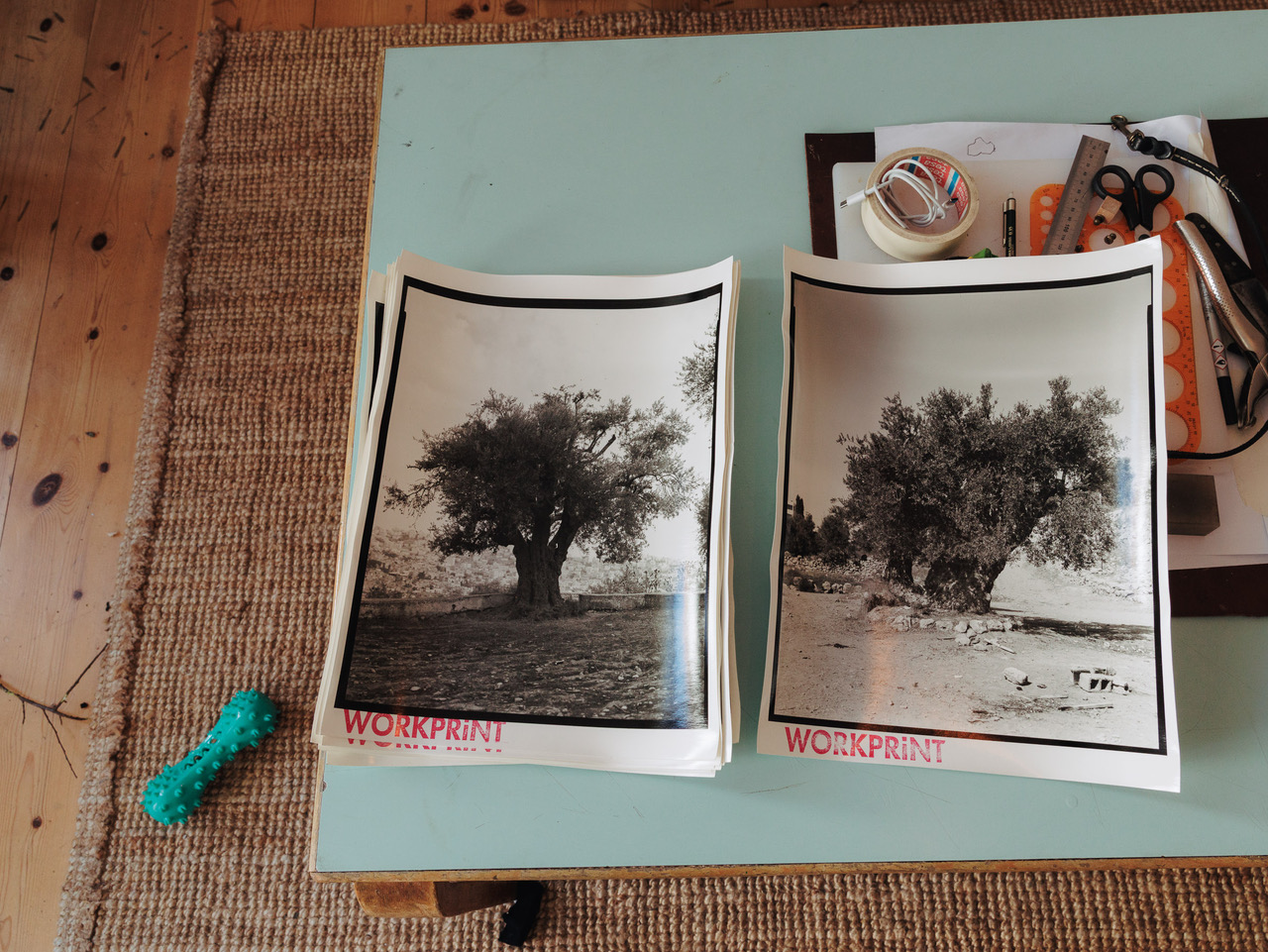

Much of Broomberg’s current output is centred around Palestine. His most recent photobook, Anchor in the Landscape, made with his former intern Rafael Gonzalez, comprises black- and-white portraits of olive trees in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Many of these are thousands of years old and stand as symbols of Palestinian identity and resilience because they are vulnerable to destruction (800,000 trees gone since 1967). It was created as part of Artists + Allies x Hebron (AAH), the NGO Broomberg co-founded with Palestinian activist Issa Amro in 2022, with the aim of confronting the ongoing oppression of Palestinian residents in Hebron by the Israeli military. A number of the original 8×10 photographs from Anchor in the Landscape featured in South West Bank – Landworks, Collective Action and Sound, the AAH-organised exhibition shown at last year’s Venice Biennale, dedicated to “works produced by artists, collectives and allies in and around the southern West Bank”.

The olive trees are the focus of other ongoing AAH projects too. With Counter-Surveillance: H2, Broomberg and co launched a counter offense to Israel’s “extensive and technologically advanced” surveillance of Palestinians by erecting a number of surveillance cameras in Palestinian olive groves in Hebron H2. Viewers can access live broadcasts of the groves via various digital platforms run by cultural institutions around the world. “It’s about using technology that’s traditionally considered ‘military’ to do something benevolent – to protect rather than destroy,” Broomberg explains. “We’ve also geolocated all the olive trees we photographed and are now working with a nano-satellite company, which has these tiny satellites that ring the Earth and deliver very high-resolution imagery of its surface every 24 hours. You can point the satellites at specific geolocations, so exactly where an olive tree is, and receive an image of it every day. It’s kind of counter archiving. And if anything happens to that tree, an alarm will go off.”

Subverting the power dynamics inherent to certain forms of photography, using the exact same forms, is nothing new for Broomberg. For the 2015 photobook Spirit Is a Bone, he and Chanarin used Russian surveillance technology to make eerie portraits of Moscow residents, in a series that reimagined August Sander’s extensive portrait of German society in the 1920s, People of the 20th Century. The same goes for Broomberg’s 2021 photobook Glitter in My Wounds, a poster for which adorns the wall between the studio’s two windows, spelling out the evocative title in red lettering.

That book was made in collaboration with the transgender activist and actress Gersande Spelsberg – who stars as its subject in multiple portraits, lit only by sunlight and mirrors – and is also a study in power disruption. “She totally directed me,” Broomberg says. “‘This is how I want to look, these are the moments I want you to capture, and if you want to try and get emotion out of me, this is how to do it’. We shot it in a day. It was really interesting; it turned the tables on the dynamic between the person photographing and being photographed.”

Collaboration seems to have remained integral to Broomberg’s practice, even since the dissolution of his most prolific working relationship with Chanarin, which was formally pronounced dead in 2021. “Definitely,” Broomberg says. “I’m hopeless with organisational or executive functional stuff so I always need to work with people to help with that. I also need to be challenged and pushed back against.”

A collaborative effort of a different kind is the room’s most lively wall, adorned with photographs, artworks and trinkets. “I have an 11-year-old son and a 15-year-old daughter, and this wall is all key memories, key things that are not only important to me but also to them,” Broomberg says with a smile. Favourite objects on the wall include the famous picture of Lee Miller bathing in Hitler’s bathtub on the day of his death. Her boots – muddy from her morning visit to the newly liberated Dachau death camp, where she had photographed the dead – are placed deliberately in frame, Broomberg points out, as is a portrait of Hitler and a statue of Venus. “It’s this performative act – it’s very radical.”

Other treasured items include a photograph of Bertolt Brecht’s chess pawn, and a picture of Broomberg’s daughter, Leni, asleep as a child. Now that she is 15, the artist says, she no longer lets him photograph her without her permission. “She’s OK with all of the pictures of her when she was little, but now she’s saying, ‘No, these are my boundaries, this is my body and you as a photographer no longer have access to it unless I give it to you’, which is amazing.”

Broomberg’s children split their time between their father’s apartment and that of their mother, the artist and architect Sarah Entwistle, who lives next door. “Honestly, I don’t think we could have created this kind of life in England,” Broomberg notes, “because I think England is still quite unforgiving in terms of what constitutes a family – this idea that it’s not broken, we’re separated parents but doing it together.”

I ask how working from home, while sharing the space with his children, has impacted his practice. “It’s kind of amazing for them to see the process, and it’s amazing for me to be present. I’m not elsewhere,” he says. “We’re always around; we’re with them but we’re also making at the same time. It’s a bit like this that you’re witnessing,” he continues, pointing to the dog, who is now playing with a plum retrieved from a bedside table. “Work has to fit in between domestic life.”

Broomberg says he misses having “a sanctified studio space, where you can totally focus”, but he adds that having one enables a certain kind of arrogance, and that abandoning that approach – like having children – has been humbling and enriching. “I’ll give you a great example,” he says, reaching for a pile of photographs of the olive trees from under his desk. “When we had these pictures hand-printed, I came back with a pile of them like this and my son came in, sat down and spent half an hour with them, really attentive. Then he said to me, ‘They’re really beautiful, papa,’ and I said, ‘Thank you’. He said, ‘No, I mean the trees’. Isn’t that perfect? I’ve done 15 books of photography, and I’ve always struggled with the notion of photography and what the meaning of it is. This was the first time I thought, ‘That’s the reason why one can do it – it’s a conduit. It’s allowing somebody else to access these things. But it’s not about me!’”

Making things that are not about him is central to Broomberg’s current practice. “Most of my work now is going between Palestine and here, a lot of planning and production, talking to people, collaborating – that’s why this space works as a studio,” he says. “Starting with my work with Gigi [Spelsberg], but mostly these past two years working with Palestinian artists, learning how to be an ally, it’s been the biggest learning curve of my life.”

Allyship has meant wrestling with and trying to counteract what he terms “the extraction value” of photography, whereby the photographer makes all the money, while the subject is left with nothing – the reason Broomberg launched his 2021 initiative, FairFoto, which uses blockchain technology to ensure subjects receive shares of the profits generated by their images. “For the Anchor in the Landscape photographs we’ve ensured that a third of the money accrued goes back into the community,” he explains. “It’s about how to make these pictures work, not for me, not for my career, not for capital, but also for the community and to bring Palestine into the public arena a bit.”

At the moment his main preoccupation is bringing the Biennale show to Berlin – to Spore Initiative, the one institution where he says “completely open dialogue can happen, because it’s privately funded”. This will open later in the year. As our conversation draws to a close, as his dog has his now-ruptured plum confiscated, I ask if Broomberg plans to leave Berlin, given all the difficulties. “A lot of people are saying to me, ‘Why don’t you leave?’ but I think it’s actually a particularly important moment to be here,” he says firmly. “There are small pockets of solidarity here in Berlin, people are getting more organised. So I’m staying here for now.”