Her labour-of-love seaside studio is not just a space for photographic practice, but for meeting, film-screening and so much more

Six years ago, Chloe Dewe Mathews decided to move to the British seaside town of St Leonards-on-Sea for three months. At least, that’s what she told herself. “Once I moved, I never looked back – that was it,” she remembers. Her studio sits on a tiny street tucked behind the main drag of the seafront. The unassuming blue garage doors belie the space inside: a large, bright room with a high vaulted ceiling, warm from the heat of the day, with photographic prints lining the walls.

This studio was a labour of love; the derelict space was sold as land rather than as a building such was its state of disrepair. “It was just a kind of orifice,” Dewe Mathews explains of the space which had previously been used for overnight car parking. “I was drawn to the proportions of the building, its shape, and proximity to the sea.” Transforming it into a liveable studio was a two-year project. “There was such excitement around the idea of creating a space that I could work in for many years to come,” Dewe Mathews recalls.

Educated at Camberwell College of Arts and the Ruskin School of Art, Dewe Mathews first worked in conceptual sculpture, installation and performance, before several years in the film industry eventually led her to documentary photography. “Having a fine art background made me comfortable in the studio situation, very keen to exhibit work instead of just seeing it in magazines,” she explains. This understanding – of the photograph as a physical object rather than pixels on a screen – informed the need for a studio space, one that is perhaps not immediately apparent in the context of a documentary photography practice.

“There’s a chaos around trying to operate as a photographer who makes work out of their spare bedroom,” Dewe Mathews says. Pre-studio, requests for her photographs required the labour- intensive rigmarole of opening sealed crates at a storage space on an industrial estate. “This was in an edge-of-town place, where there’s grit and sand whirling, and I’m trying to drill open these massive crates to take one of the pictures out,” she recalls.

From a practical perspective, having a space to store archives, and show prospective buyers or exhibitors her work, is indispensable. And so is having a blank wall to mock up sections of a show in advance rather than designing it on a computer, where sizing or spacing might not translate to the installation. “All the details of the way work is sequenced, the sizes, the way text relates to image – those relationships are crucial, and they make up what the final work becomes,” she says.

Space to create

“A studio creates a different type of meeting between friends and colleagues,” Dewe Mathews says, reflecting on the subtle, psychological experience of being in the space. “It’s not the same as going to the pub or to a cafe; there’s a very different atmosphere. Different conversations take place, different thoughts take place.” In the winter she hosts film nights and, post-pandemic, the plan is to run talks and workshops, as well as offering residencies. The studio as a place to gather, as a space to be shared with other artists.

The space has also allowed the photographer to separate her working life from that of her life as a mother. “I’ve felt so lucky to have done it before I had a child,” she says. “So many people talk about how your identity is compromised, squashed; you start questioning your own previous life, or your creativity. To have a space that you can return to that is just your space, where you have a sort of calm and a consistency, rather than it being a spare room at home: that’s invaluable for me.

“It’s a shame that we’re led to believe that having a studio is a luxury,” she continues. “But it’s partly because of the obscene cost of property in this country that nowadays a studio is not something that every artist and photographer has. Go back 30 or 40 years, many artists had great studio spaces in central London.”

Now, many artists cannot afford to live in London at all, let alone have an extra studio space there. “It’s a shame that’s seen as surplus to requirement. Making photographs or films, the actual shooting could take 1 per cent of the time. What makes up the rest of your working day, and what do you actually do? It’s research, it’s preparation, it’s communicating with people. To have a space to do that in is important.”

Go with the flow

The beach is a short stroll from Dewe Mathews’ studio door, and she swims in the sea every day. The ritual allows her to observe her surroundings, “having a moment to notice the colour of the sky, notice what the weather’s like”. On this particular July day, there’s a stiff breeze at the water’s edge, a hazy, potent kind of summer sky, and the English Channel – often brown – is a mild granite green.

“There is something [to the idea] that water and swimming are the perfect antidote to modern life. It’s that complete immersion and therefore separation from what exists on the other side, above the water; the chaos of life. Whether it’s the stress and complexity of work, screen time, or just a busy mind.”

It is striking how water has found its way into Dewe Mathews’ work. In Caspian, which Dewe Mathews started in 2010, the photographer explored the region around the Caspian Sea for five years. And in Thames Log she spent another five years examining different shades of human interaction with the London river. “There’s great poetry and openness and ambiguity in the element itself,” she says of water.

“So that lends itself to reflecting, or embodying human activities in different ways.” That said, Dewe Mathews’ inclination towards water has been unconscious; a spring bubbling up beneath its own momentum. “It’s funny, isn’t it?” she says. “You realise there are these currents running through.”

Having the studio as an anchor – the fixed point where all the work and materials can be gathered – also affords an artist the freedom of experimentation and the possibility of change. “I don’t see my work as staying the same,” says Dewe Mathews. “I want it to be free to move in whichever direction makes sense. So although I normally photograph somewhere else and then produce, edit or think about the work here, I also want to have the possibility of allowing it to grow.”

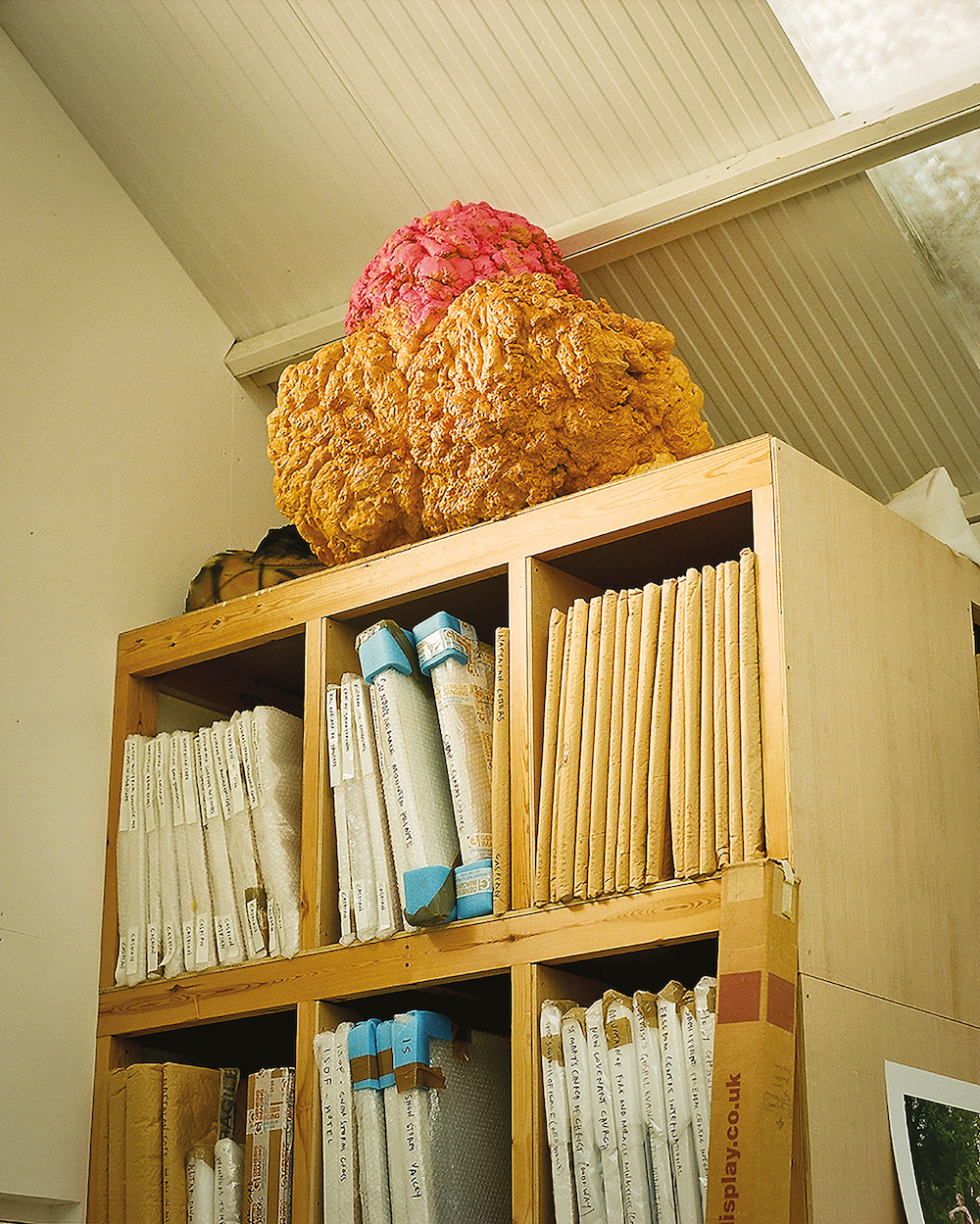

As well as photographs, Dewe Mathews makes books, films and installations. In the future she hopes to evolve her practice further. “I used to make sculpture, I used to do performances – who knows what I’ll do? Who knows what will happen? I don’t want to just set up a space that’s only for the thing I’m doing today; it’s about thinking more long- term.”

Just as the sea looks different each morning, Dewe Mathews is open to change, to transformation. “I hope I stay here for a long time,” she says. And above our heads, seagulls arc then dip to the water’s edge.