London-based artist Leah Clements is committed to building disability inclusivity into every part of her practice. Here, she discusses the importance of remote access, open resources, and mutual support

When we think about how disability is portrayed within wider society, it is often presented as something to be feared, pitied, or cured. But the experience of being a disabled or chronically ill person in the world and connecting with sick or crip communities can be an affirming, expansive and fulfilling journey.

Artist Leah Clements has done much to progress disability inclusivity in the arts. Her open access resource, Access Docs for Artists, co-created with Alice Hattrick and Lizzy Rose, provides useful information and templates on writing access riders (a document detailing a person’s access needs). Meanwhile, Clements is continually considering how her creative practice is engaged with and viewed, placing access adjustments at the forefront of all she does.

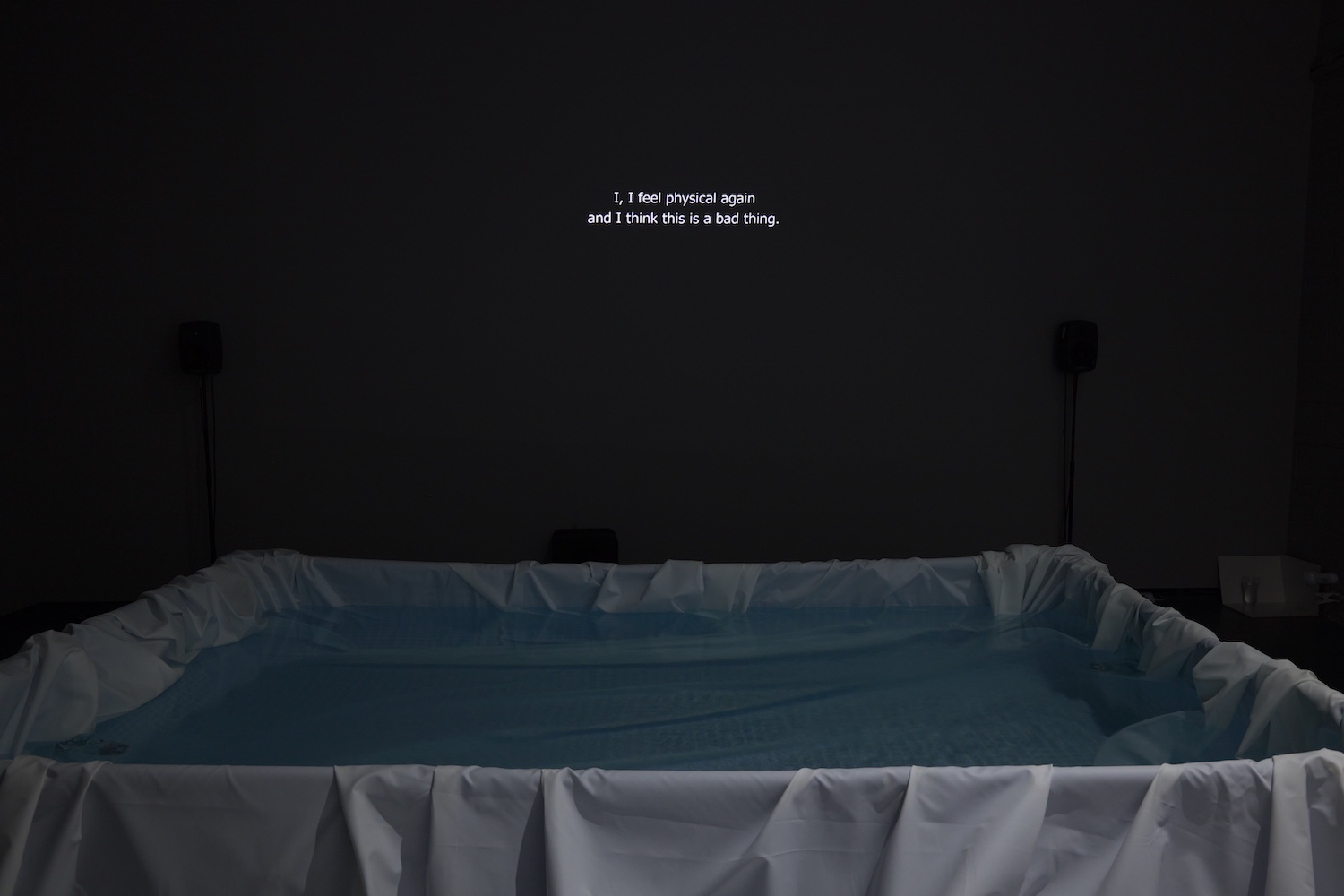

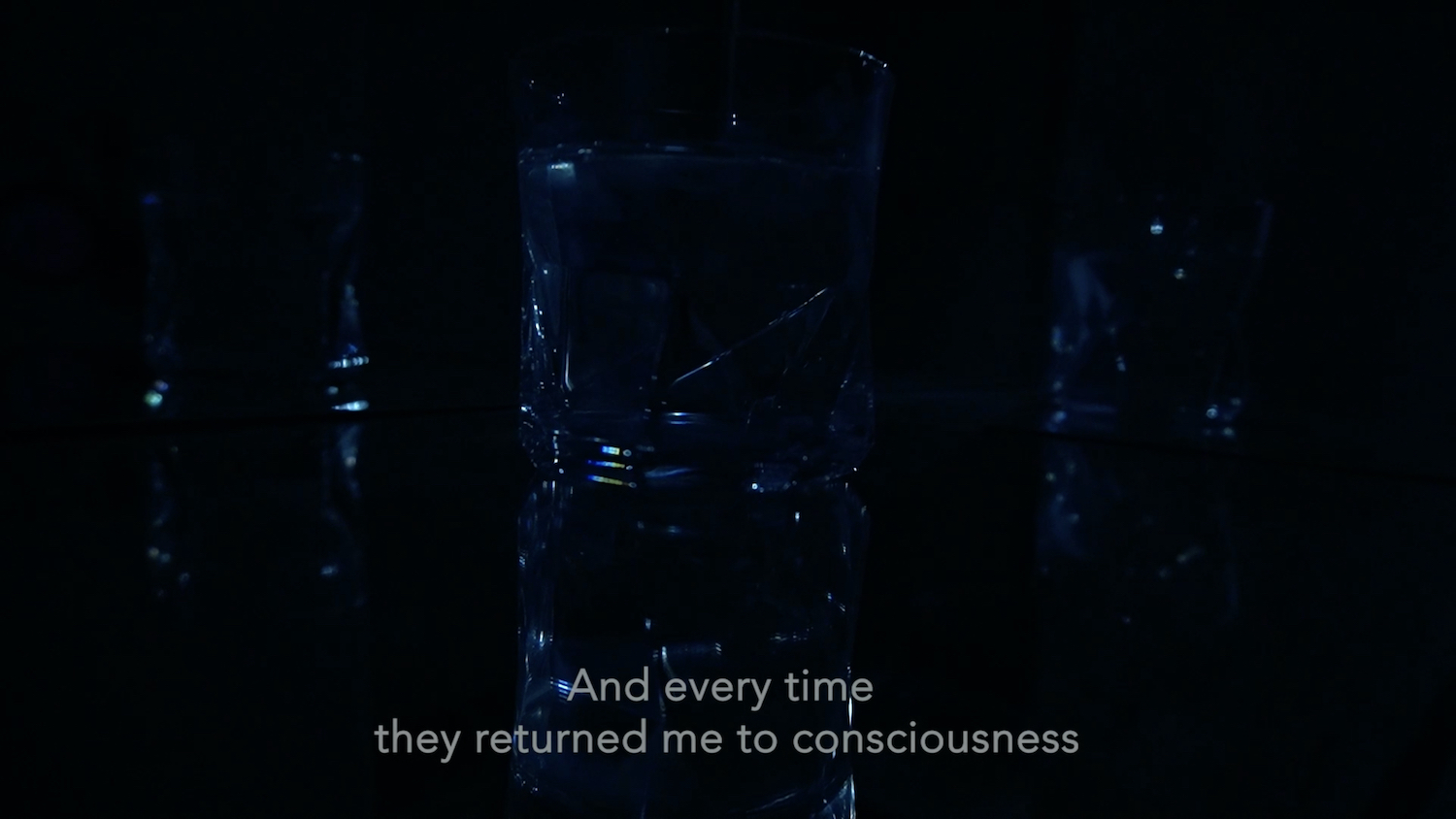

For Clements’ current exhibition, The Siren of the Deep, on show at Birmingham’s Eastside Projects, the artist re-imagines the remote viewing experience for those who cannot physically access the space. Instead of a direct visual representation of the show, Clements’ work asks: “If this exhibition were a film, what would that look like?”

Here, Jamila Prowse speaks to the artist about how we might move towards greater disability inclusivity in the arts.

Jamila Prowse: Why did you decide to make a film version of your current exhibition, The Siren of the Deep?

Leah Clements: I wanted to make a film so that people who can’t leave their house or can’t make it to the show for disability, economic, or other reasons, would still be able to see it in some way. I would have done this had Covid-19 never happened, but it feels especially important now as I’m feeling a collective sigh of disappointment from the disabled community about all of the art stuff that had gone online, but is now disappearing from the digital space to exist again only in-situ as lockdowns are ending.

I’m trying to remain tentatively hopeful that if we keep pushing then this can be rectified, and that we can continue to make art available to people at home – as so many galleries and art organisations did during Covid – building on what was created during lockdowns to do better for everyone.

JP: How do you view the relationship between art making and access adjustments?

LC: The artist Shannon Finnegan runs a workshop called ‘Alt-Text as Poetry’, and image descriptions really can be read that way. If you think about the descriptions of your images as poems, then it can become this expansive, textured, layered practice. Not all access adjustment production will be super creative and fun, and it shouldn’t all fall on the artist, especially when that artist is disabled themselves and might need more support with the production of everything around the show. Unfortunately, the responsibility often does fall on them, because disabled people usually think more about other disabled people.

BJP: What are the benefits of collectivising knowledge, and building open resources of tools to be shared within disabled communities?

Leah Clements: I have an email signature that briefly states I have a chronic illness and it might take longer for me to respond to emails, the outline of which I nicked from Alice [Hattrick], and I know other people have now nicked from me. I think of it as the digital, crip equivalent of when people used to rip cassettes in the USSR, and pass around these forbidden bootlegs that you never knew the exact origin of. It’s like a clandestine way of spreading culture – getting hold of the things you really need to thrive, in a sort of note-passing way.

There’s something about this collective pooling of knowledge and tools that re-collectivises us from our individualised pathologies or whatever medical healthcare system process we’ve been through, and makes us visible on a bigger scale. We give each other the confidence to state our needs, create our boundaries, get what we need, and we are a lot harder to ignore or dismiss when there are so many of us shouting in chorus.

I think a lot of us really want to dispel or push against any art-world notions of scarcity, which mean pitting us against one another as competitors, and to turn more towards mutual support.

Leah Clements: The Siren of the Deep is on show at Eastside Projects until 31 July 2021.