Coded bias

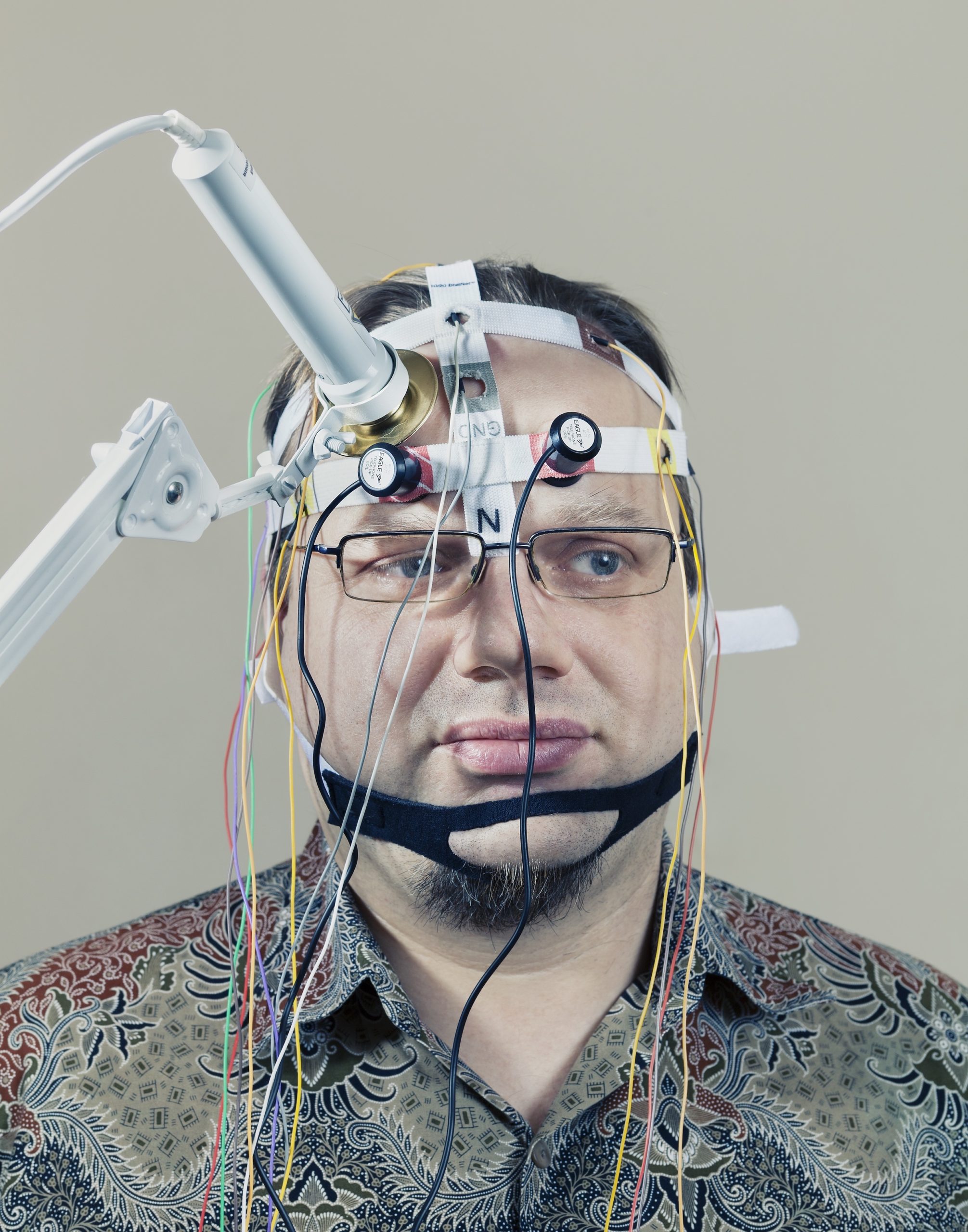

There are other dangers relating to this arm of technological innovation, specifically with artificial intelligence (AI) and its possibility to surpass the power of the human mind. From Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, to Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, dystopian visions of sentient inventions rebelling against their creators have long been explored in fictional narratives. But many experts are calling for caution. Professor Nick Bostrom [above] is the founder of the University of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute. His team of 20 researchers explore existential threats of emerging technologies to the human species. In his 2014 book, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, Bostrum states that if a machine is able to surpass the human brain in general intelligence, this new “superintelligence” could replace humans as the dominant lifeform on Earth. “We should not be confident in our ability to keep a superintelligent genie locked up in its bottle forever,” he warned in a 2015 TED talk.

It is not only hypothetical threats: the existing dangers of AI are far more insidious. Big brands and tech giants are already leveraging it in marketing campaigns, and recent reports have shown how algorithms are adopting sexist and racist biases. “All these prejudices we have as humans are built into these technologies. It could reflect our good side, but also our bad side,” says Vintiner. Fletcher adds that it is important to consider who has access to this power: “It’s very white, it’s very male, it’s very middle classed, with not much in between.” Unfortunately, most of the “big money” being pumped into AI is coming from the advertising industry and the military, Vintiner adds. The most terrifying prospect is how they will harness it when machines become more intelligent than humans. “The military and ad agencies will probably get there first. And when that happens, it’s game over.”

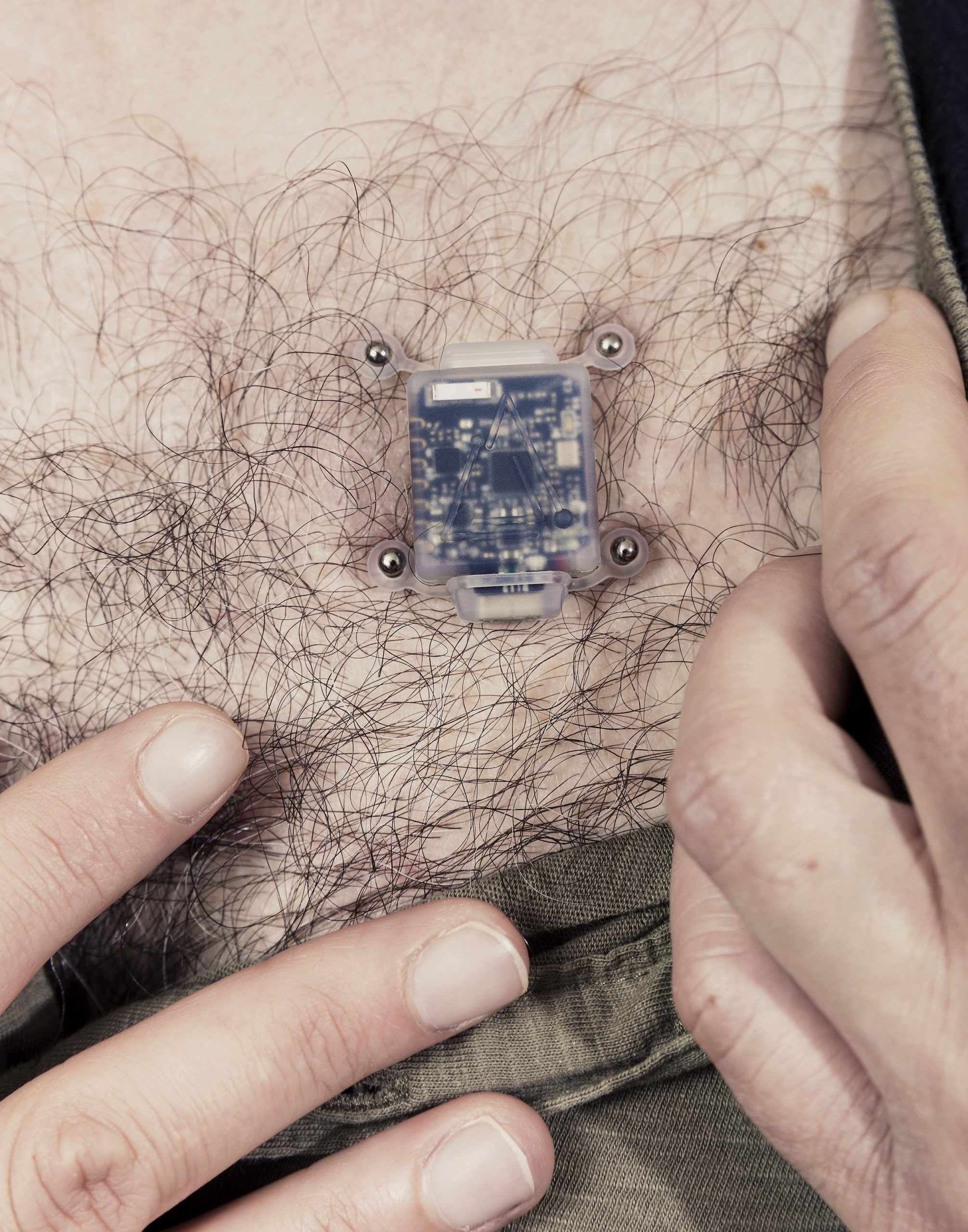

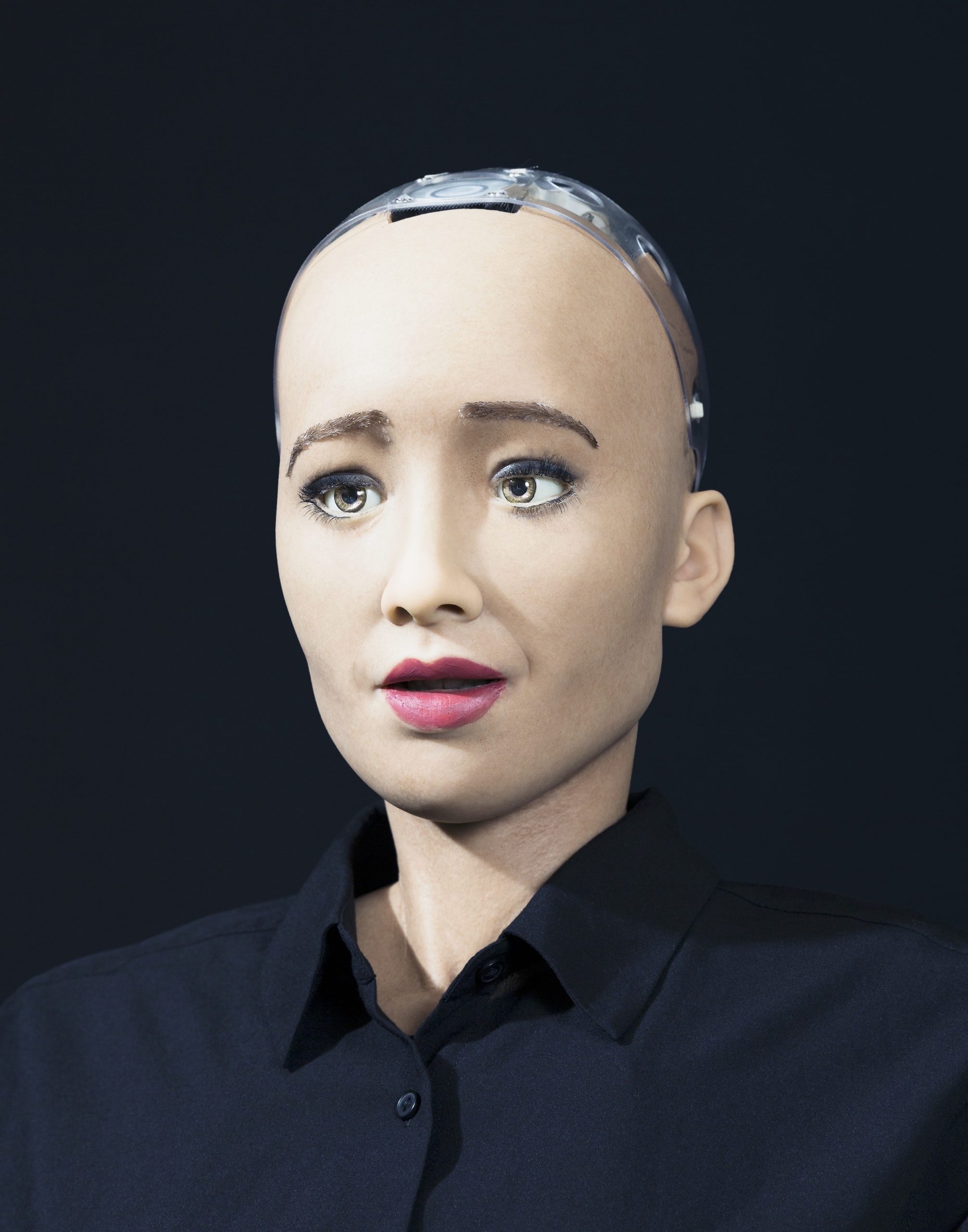

All of this has driven Fletcher to reconsider the ideas of some of the individuals they have met. Ben Goertzel is the former chief scientist at Hanson Robotics, and co-creator of the most advanced human-like robotic AI, Sophia [below]. Goertzel advocates for the potential of machine learning to enhance our lives – in the service industry, or medical care, for example. Then there is Benjamin Engel, who is in the early stages of developing a skull implant that will enable him to sense the collective mood of Twitter’s trending topics. Engel is a ‘Grinder’, a branch of transhumanists also known as ‘bio-hackers’, who practice actual implantation of cybernetic devices to boost functionality and performance. This may sound extreme, but for many transhumanists, assimilation is the next logical step in our relationship with technology, and it is not a question of if, but when these technologies will be capitalised by tech giants and pharmaceutical companies.

“We’re already participants in their capitalism, and we do it even though we’re completely cognisant of what’s going on,” says Fletcher. “Now, when I think of people like Benjamin Engel, I realise that what they’re trying to do is get an edge on it, before it’s taken out of their hands, before it’s something that is privy to the rich… They’re trying to evolve themselves before it’s not an option.”