In collaboration with Direct Digital – the leading international photographic equipment rental service – 1854 Media and British Journal of Photography presents Industry Insights, a series delving into the ins and outs of working in the photography industry.

From physical books that transport us to different worlds, to connections sparked at book fairs, the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy unpacks the potential of the medium

Bruno Ceschel started Self Publish, Be Happy (SPBH) in 2010, originally as a way of gathering the self-published materials that had hitherto lacked a shared space. Over the past decade SPBH has amassed a vast collection – recently acquired by the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris – and produced a publishing house, SPBH Editions. The organisation has worked with major international galleries including Tate Modern, C/O Berlin, Foam, and Aperture, and today focusses a great deal of energy into mentorship, education and running workshops online and IRL (the next is scheduled in Rome in September, pandemic permitting).

As expansive a project as it is, the through line is the community that has gathered as a result, a community that has “transcended the books themselves”, and with whom the project is in constant conversation. It is, Ceschel says, “the centre of our interest and work”. Book fairs – the NY Art Book Fair, Paris Photo’s Polycopies, and London’s Offprint, for example – are where this community amass, leafing through stacked and colourful displays, searching for treasure.

“You go back to your family, a weird, dysfunctional one,” laughs Ceschel, “but you go back. It’s the same with the art fair. You have your drunken night with people that you see twice a year; you have your romance; you see stuff”. He points out that the physical experience of the medium is central to other ways in which we experience art. A visit to the Tate is not just about the picture on the wall, but being in the space, carving out the time to use your attention in a particular way. Watching a film on a laptop is different from sitting in the cinema, quiet as the lights go down. “God, how boring is life without it?” says Ceschel. “If you take the community out of the books, it’s just not the same.”

What was the draw towards photobooks in the first place? For Ceschel, there are the familiar reasons: photography’s suitedness to the printed page, to being experienced in sequence. Also, though, it’s a way of teasing out ideas, applying order to a project which may, until the book-making stage, feel abstracted or provisional. “You have this unformed body of work, and you start figuring it out, and then you go over and over again until it becomes this really punctual and effective way to communicate ideas and emotions,” Ceschel explains.

A book is also a way of making something tangible or permanent. “We basically don’t have any record of a lot of early digital art,” says Ceschel. “A lot of artists have been working with digital material and putting it to paper, because effectively it’s the only way that we can preserve images for posterity. We haven’t figured out another effective way to do that.” A book is definitive: it exists in the world, more than a project might have if it remained a set of image files scattered across a series of hard drives. “To me, there’s an amazing thing about making this object,” says Ceschel, “and thinking that the object will exist in the world for decades to come”.

“The expectation of what a photobook looks like can be challenged, and should be challenged, at all times”

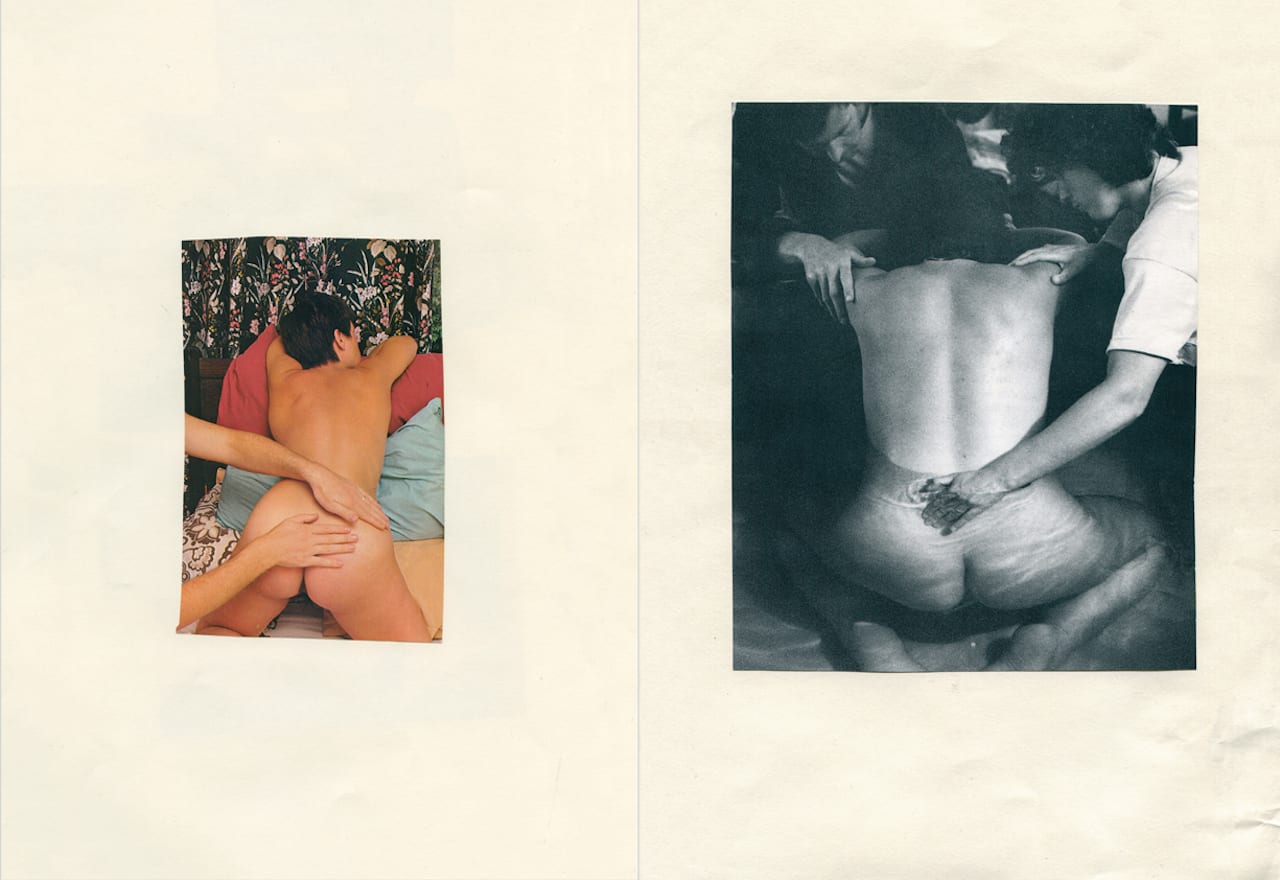

The organisation’s publishing arm, SPBH Editions, aims to expand the possibilities of the photobook. “We’ve never done archival material, or more traditional bodies of work,” explains Ceschel. “We want to expose projects that don’t find other places to exist.” He recalls working with installation artist Felicity Hammond over a period of years, considering the best way to interpret her work in book form. A trip to Venice and a chance encounter with a printer, who was making a children’s book involving cut-outs, led to the creation of Property. In a similar vein, Carmen Winant’s 2018 book My Birth used completely different material to her celebrated installation at MoMA. Ceschel is not interested in producing exhibition catalogues, or shoehorning an installation into a 2D format.

“The expectation of what a photobook looks like can be challenged, and should be challenged, at all times,” Ceschel says. “It’s interesting to see how the language of photography is changing, and how we can use it.” Making a book in which the physical form reflects the conceptual qualities of the work it contains contributes to this evolution. “There is something very powerful in creating a book that is a vision of a photographer, that doesn’t want to obey or follow any set of rules that are imposed by the market,” he reflects.

This challenge is something that Ceschel actively cultivates through the mentorship and workshops that he runs with SPBH. “You are there to facilitate this explosion of possibilities and ideas,” he says. Rather than emphasising an end result, his workshops focus on the journey, experimentation, and play. “From the beginning we say actually, this is about the ride,” he explains. “One should just let him or herself go, and explore this possibility… Part of me thinks that there are no rules. That’s the beauty of it.”

“To me, the more interesting examples of self-publishing are actually by emerging young photographers,” he continues. “I think there is an interesting energy in these publications. People further along in their career have a set of expectations about what form a photobook should take.” Young practitioners often seem to work with a certain freedom – a “beginner’s mind” of sorts – that established artists might no longer have access to. “I think the results are pretty amazing, because my favourite photobooks often are not very expensively-made objects,” says Ceschel.

Central to the SPBH cosmology is its belief in the way in which books can transport us. “Images have an incredible power,” says Ceschel. “We experience the lives of others through Instagram. Immediately you are inside a fantasy, a construct in the life of somebody else.” Ceschel’s belief in this power, and the way that visual art can provide a language which opens up possibilities, is rooted in his childhood in Italy. “I was a queer kid, and it took me ages to figure out who I was,” he recalls. Books and photographs gave him access to other languages, other worlds. “Maybe because it comes from a very personal experience, I always in a way try to facilitate that, as much as I can.”

And it’s not just accessing other parts of our current world, or other versions of a life, that is made possible by books. It’s also the construction of new worlds; different possibilities entirely that shift and glitter on the horizon of our mundane lives. “I always admire how artists actually manage to create worlds,” affirms Ceschel. “You’re suddenly in another place which is full of possibilities, hopes, sometimes challenges.” This opening up to other possibilities is especially pertinent now, of course, during the pandemic and its ongoing lockdowns. “More and more it seems that we need this portal to other possibilities – all of us,” Ceschel says. “And they should be made available to others.”