On the day of US President-Elect Joe Biden’s inauguration, the Mexican photographer reflects on her Female in Focus 2020 winning series, conceived last year in a bid to convince American citizens to vote Trump out of office

In January 2020, a group of Hondurans organised a large migrant caravan headed for the US-Mexico border. Embarking from the northern city of San Pedro Sula — dubbed by Western news outlets as the ‘murder capital of the world’ (often with little acknowledgement of America’s connection to its gang brutality) — hundreds of Central American men, women and children boarded the vehicle in the hope that when they alighted at their destination, they could carve lives free from violence, persecution and poverty. For eight days, they travelled across Guatemala, before reaching the Suchiate River on the Mexico border.

Historically, Mexico’s President Andrés Manual López Obrador has called for safe passage in such instances. But in the spring of 2019 — following a series of threats to cut foreign aid to Central American countries unless their governments forcefully cracked down on the northern flow of undocumented migrants — US President Donald Trump stunned officials when he promised tariffs on all Mexican imports if López Obrador did not comply. The migrant caravan of January 2020 is the subject of Ada Trillo’s Female in Focus 2020 winning series; needless to say, it never reached its destination.

“My brother has lived in Mexico all his life,” says Trillo, born in Juarez, just south of the Texas border, before moving to America aged 18. “He said to me recently, ‘I never knew there was so much hate in the US.’” Trillo’s winning series, La Caravana del Diablo, follows her earlier migrant series La Bestia (2017) and La Caravana (2018), all three of which she felt compelled to document after witnessing the brazen inhumanity of migrant detention camps in her native city as a volunteer. “Some people really don’t have a lot of knowledge about Central America,” she says. “They think they’re coming here to steal their jobs or commit crimes. But they’re parents, students and children, with hopes and aspirations. They’re coming here to work. They’re coming here to contribute to society.”

“Some people really don’t have a lot of knowledge about Central America. They think they’re coming here to steal their jobs or commit crimes. But they’re parents, students and children, with hopes and aspirations. They’re coming here to work. They’re coming here to contribute to society”

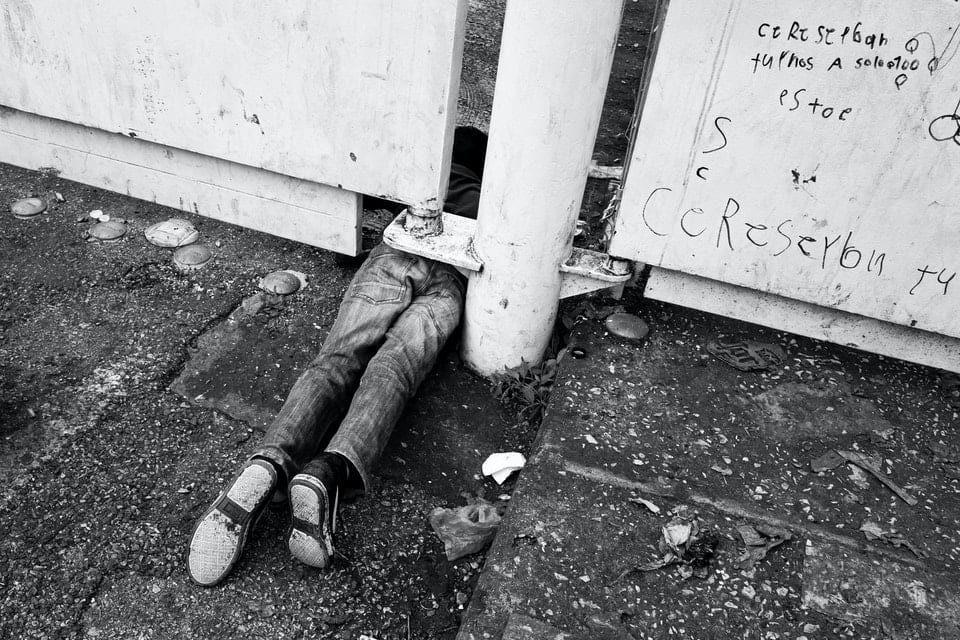

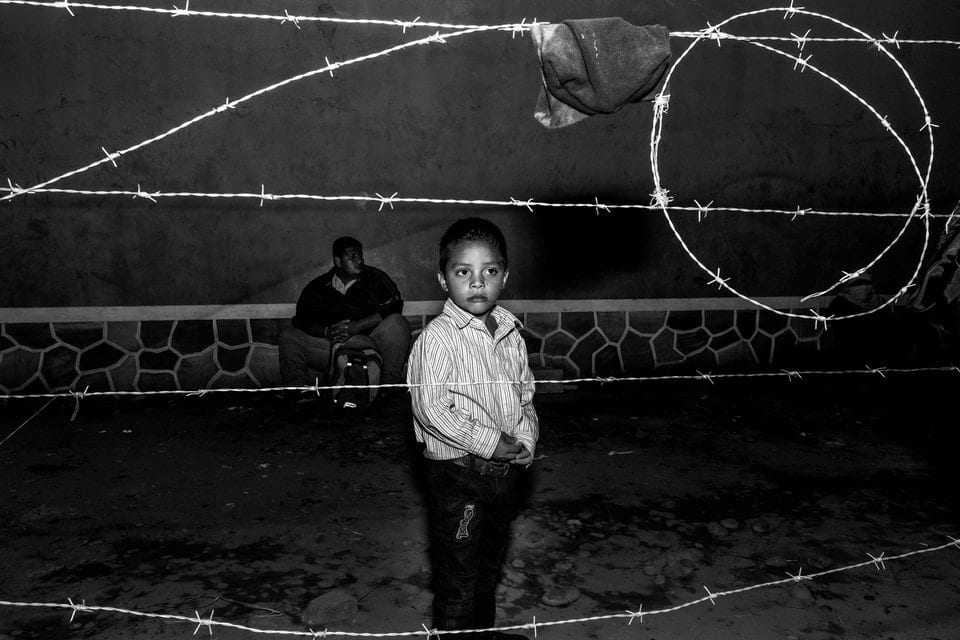

In particular, La Caravana del Diablo was conceived to highlight the devastating impacts of Trump’s anti-immigration policies on the lives of Central Americans ahead of the 2020 Presidential Election. The solemn black and white series — immersively shot by Trillo, who ate, slept and travelled with the group — captures various points on the migrants’ journey: we meet Ashley, a 27-year-old trans woman from Honduras, where murder rates for the LGBTQ+ community are among the highest in the world; 6-year-old José, waiting patiently behind a barbed wire fence at 3AM to cross the Mexican-Guatemalan border, and young Chelita, clinging to her mother amidst the chaos. Perhaps most harrowingly, the series shows the moment the caravan clashed with Mexico’s Guardia Nacional (established from former federal, military and naval police in 2019, in response to Trump’s demands) on the Suchiate River.

Splitting into two groups, the larger one was savagely tear-gassed, resulting in chemical burns and other grievous injuries. Forced to retreat, they slept in cardboard boxes on the river’s edge for two nights, before successfully crossing at 4AM — only to be cornered once more, and forcibly loaded onto buses bound for Honduras. Trillo recalls numerous group members who kept her safe: welcoming her in, finding her places to rest, holding her above water when her backpack was dragging her down. “That’s just how they are,” she says. “They become your friends. They become your protectors. And all of a sudden, you’re seeing these friends — that you slept next to, that you had dinners with, that you walked miles with — being apprehended by the military. Tear gassed. And you can’t do a thing. The only weapon you have is your camera.”

The second group amassed in the border town of El Ceibo, Guatemala, where Julio Cesar Sanchez Amaya, Mexico’s Head of Foreign Relations, welcomed migrants in groups of ten. But after a brief stay in detention centres, they were deported back to Honduras against Sanchez Amaya’s word; back to lives of extortion, impoverishment, or even death. “I’m Latina,” Trillo says, resolutely. “When I think of migrants, they’re my people. And Trump has been denying them their fundamental human rights.”

Following Trump’s fraught election defeat, still contested by many Republicans, President-Elect Biden and Mexico’s President López Obrador have committed to working together on a “humane strategy” for regional migration by addressing its root causes in Central America and southern Mexico. Moreover, in a historic shift from Trump’s anti-immigrant agenda, it was this week announced that Biden, once sworn in, will immediately ask Congress to offer legal status to an estimated 11 million “illegal” migrants in the country.

There is hope on the horizon for a more compassionate America — but with an acutely polarised population, and socio-political unrest continuing to burgeon, the path remains an unsteady one. In any case, says Trillo, “Trump’s xenophobic policies toward immigrants and asylum seekers will be felt for generations to come.”