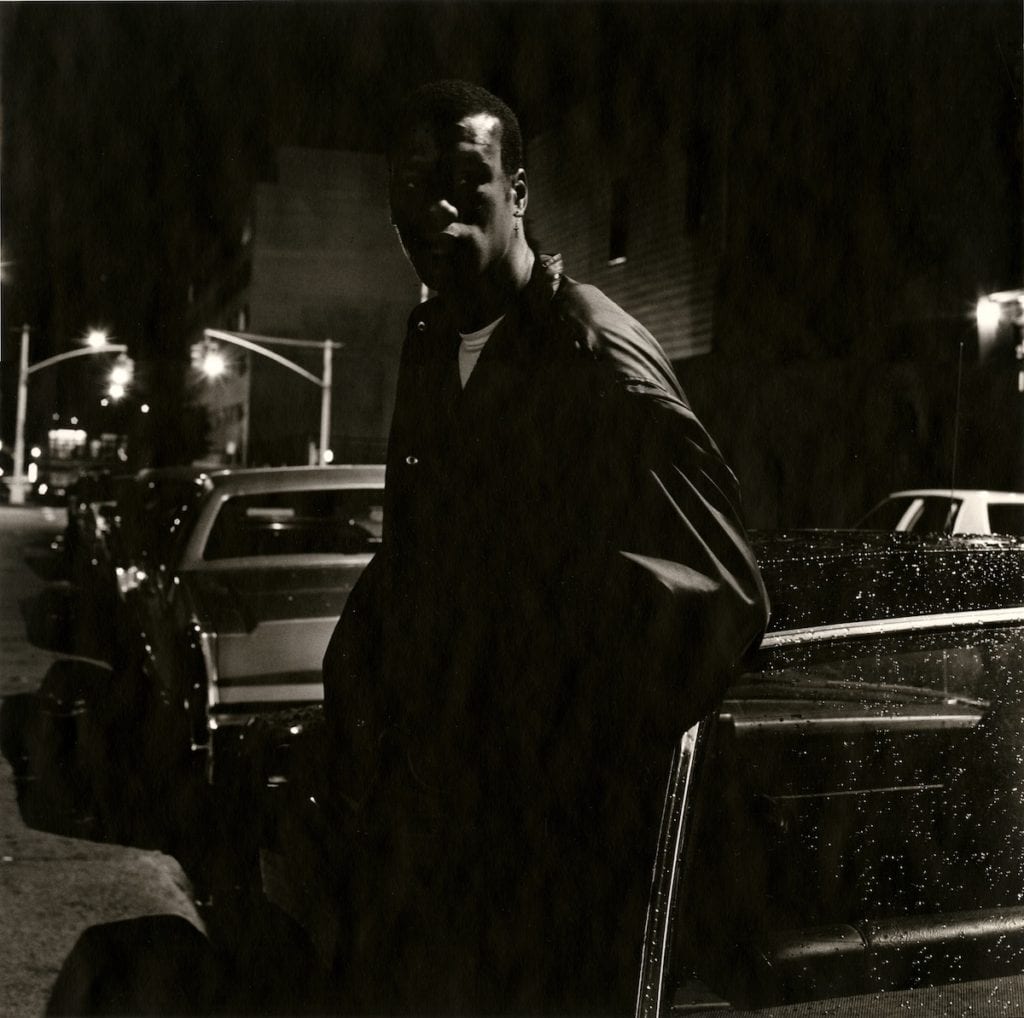

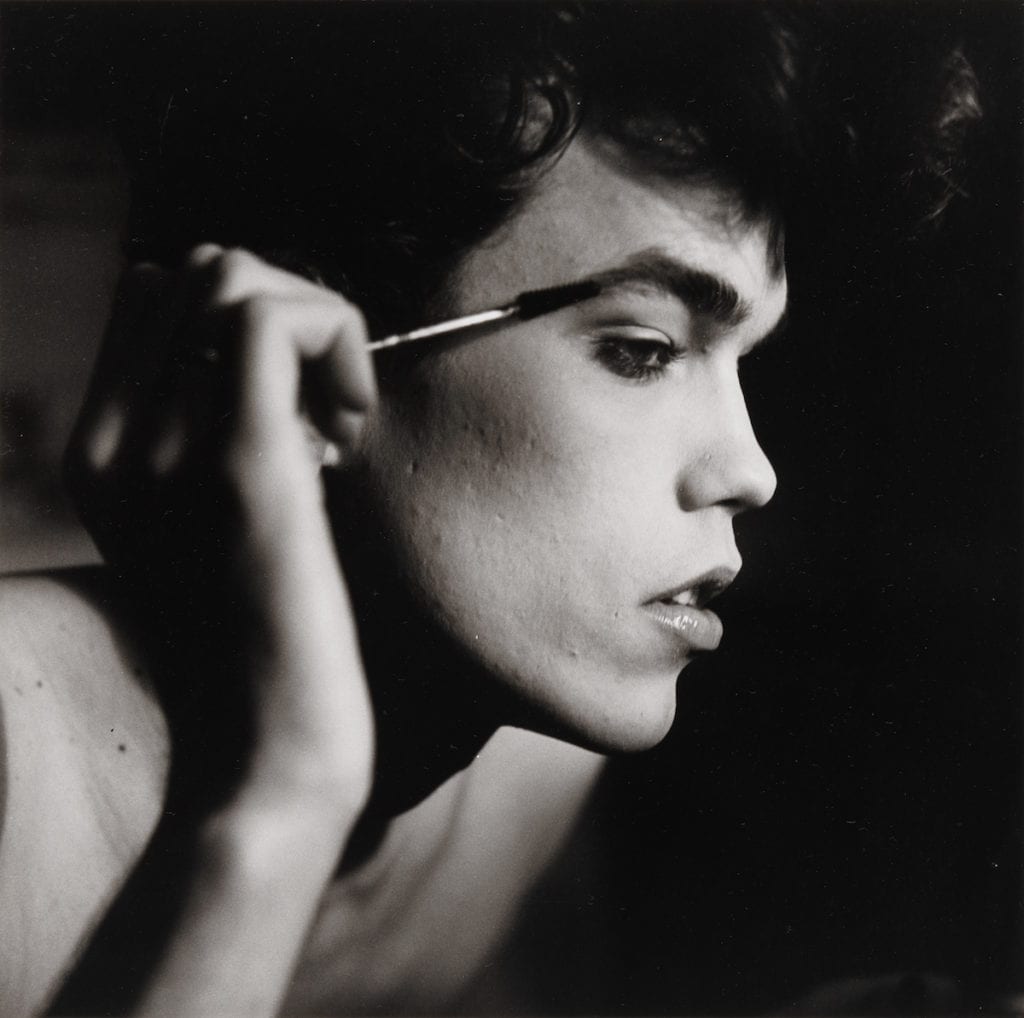

Peter Hujar was a central figure in the downtown-bohemian-scene of New York City, which emerged at the end of the 1960s and flourished until the advent of the AIDS epidemic in 1980. Intellectuals Susan Sontag and Fran Lebowitz were among his friends, along with fellow artists Paul Thek, Andy Warhol, and David Wojnarowicz. Hujar photographed his companions and other acquaintances — men, women, drag queens, transgender people — often at his low-rent loft on 12th Street, Second Avenue, above the Eden theatre. His powerful black-and-white portraits crystallise and celebrate their sitters, and a selection of these, alongside several landscapes, are on show in Peter Hujar: Cruising Utopia — an online exhibition at Pace Gallery that runs until 28 July 2020.

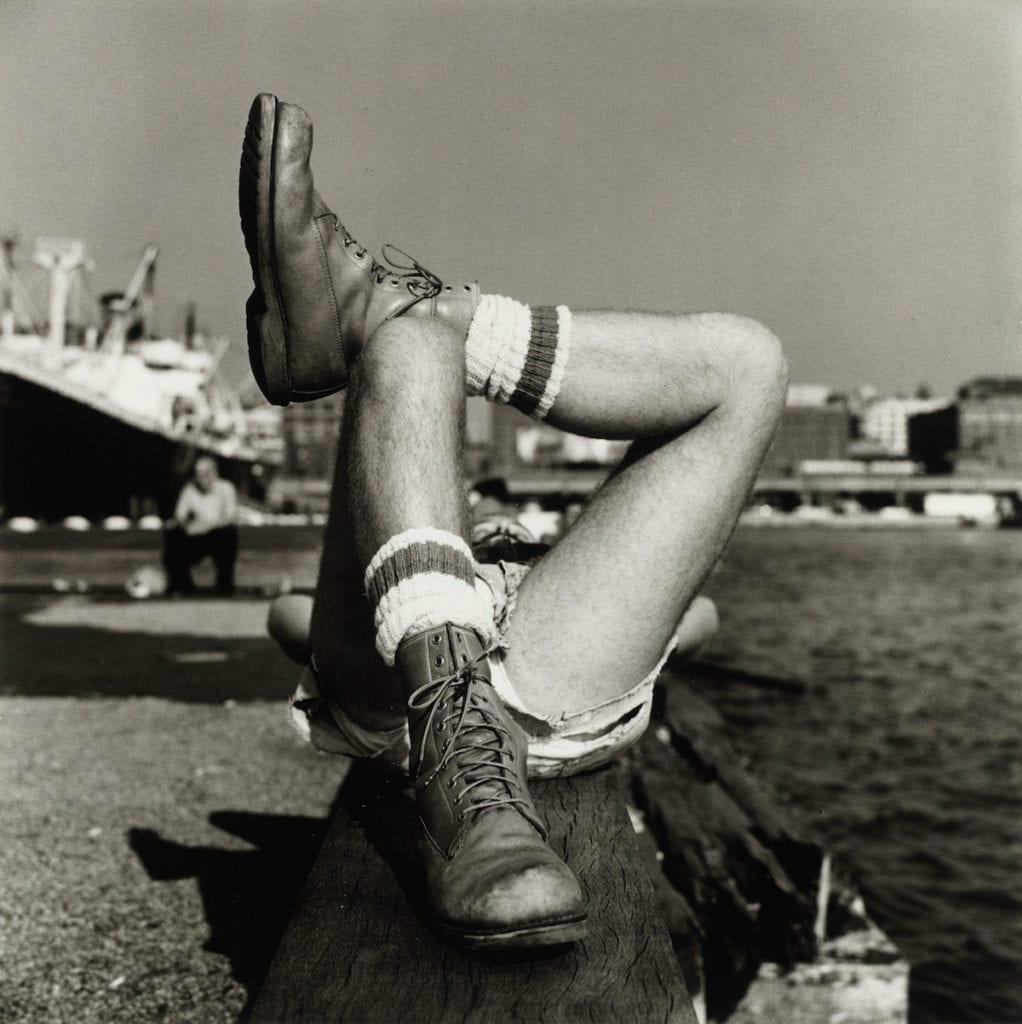

The 19 exhibited photographs — some iconic, others rarely seen — were taken between 1966 and 1985: a significant period for queer counter-culture in New York City. The 1969 Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village marked the advent of the modern gay rights movement: prefacing the formation of gay rights organisations, a more activist LGBTQ civil-rights movement, and the conception of annual pride marches. Hujar partook and captured the flourishing post-Stonewall scene, which emerged in downtown New York City during the 1970s and early-80s. He photographed evocative portraits and landscapes: in one a man relaxes at the Christopher Street Pier — a famous cruising spot on the Hudson River — while, in another, Hujar hones in on the impassioned embrace of two men — Jay and Fernando — dressed in leather.

Sexuality seeps through all of Hujar’s work. Whether it’s a subtly alluded to through an image of the Westside Parking Lots — a location emblematic of sexual activities, further amplified by a barely-visible advertisement for leather captured on a building in the distance — or overtly depicted, as with an image of the artist Paul Thek masturbating on a striped couch; his eyes closed and head thrown back in pleasure. “I can think of few other photographers in which sexuality is as much a constituent part of how the photograph came into being,” explains Oliver Shultz, curatorial director at Pace Gallery, New York.

In 1970, Hujar shot the photograph for the now-iconic “Come Out!” poster for the Gay Liberation Front — a movement founded to champion the queer community in the aftermath of the Stonewall uprising. “Hujar was not directly involved in politics — he was not out there protesting; that was not his way of engaging,” says Shultz, “but he did date a guy called Jim Fouratt who was a civil-rights activist, and participated in the Stonewall uprising along with Hujar.” Fouratt would help found the Gay Liberation Front and Hujar also became involved; a year after the Stonewall Uprising he organised the taking of this photograph. The image is not densely-populated — homosexuality was still illegal — however, visually, it brings the queer community out of the domestic realm and other covert spaces, into the public sphere: “It is a famous moment in the history of gay rights in America,” continues Shultz, “and it is interesting that Hujar plays a visible role in that.”

“Somehow the water has a personality — it is like he is treating its surface as a face”

Oliver Shultz

The intimacy with, and between, his subjects, which weaves through Hujar’s oeuvre, has always been a defining element of his work: Hujar famously said: “I want people to feel the picture and smell it”. And this element resonates particularly strongly now during a pandemic when touch has become such a loaded and dangerous thing. “One of the images in the exhibition shows Jay and Fernando – two men in leather — locked in this incredibly passionate kiss, and, at least for me, I cannot help but look at that image and think about what it means to be proximate to other bodies in an era of contagion and fear around contagion,” reflects Shultz.

Hujar is well-known for his portraits of the illustrious members of New York’s downtown scene. Less-known, however, are his photographs of the landscapes of New York City, including those of its piers — emblems of the cruising culture of that period. “They are very closely tied to the logic of the studio portraits in a way because Hujar treats all his subjects as though they are sitting for portraits,” says Shultz, “even when he is photographing an empty parking lot or the surface of the water.” Hujar’s photographs of water are compelling, capturing the curves and ripples of its surface and transforming them into sculptural entities: “Somehow the water has a personality” continues Shultz, “it is like he is treating its surface as a face”. The exhibition, by no means comprehensive, does, however, draw such parallels across Hujar’s work: tracing the connections between his portraiture and street-photography — genres that are often treated as distinct.

Despite this prolific documentation of LGBTQ life, Hujar published just one book during his lifetime: Portraits in Life and Death. The publication, which garnered mostly negative reviews, blends images of the artist’s friends from 1974 and 75, juxtaposed with several photographs of catacombs in Palermo, Italy, taken over a decade earlier. Life accompanies death: a dichotomy, which is uncanny in its foreshadowing of the 1980s AIDs-epidemic that ravaged Hujar’s circle, the LGBTQ community at large, and ultimately claimed the artist’s life in 1987. In the book’s foreword, Susan Sontag professes, almost prophetically: “Photography … converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also — wittingly or unwittingly — the recording-angels of death … In … this selection of Peter Hujar’s work, flesh and moist-eyed friends and acquaintances stand, sit, slouch, mostly lie — and are made to appear to meditate on their own mortality.”

Fittingly, the final image of the exhibition depicts David Wojnarowicz: hollowed cheeks sucked in as he drags on a rolled-up cigarette. Hujar met Wojnarowicz — who was twenty-years his junior — in a bar in the East Village in 1981; the pair were briefly romantic, before becoming close friends. Hujar mentored Wojnarowicz, inviting him to live at his loft on Second Avenue and Wojnarowicz remained by Hujar’s side as the photographer slowly passed-away from AIDs. “David was the final chapter of Peter’s life,” says Shultz, “one can see the possibility, the generativity, and the generousness of that relationship and how much it could have been.” It is that sense of unrequited hope and opportunity, which is captured in the exhibition’s title: Cruising Utopia — a reference to a book by José Esteban Muñoz of the same name, which posits the notion of queerness as an imagining of a possible future, and thus a kind of utopian project. “The image of David signifies the plenitude of possibility, which is still embedded in the body of work that emerged from six years of closeness between the two artists — a relationship that ended in tragedy as they both died of AIDs-related illnesses,” continues Shultz.

Despite the richness and significance of his practice, Hujar was largely overshadowed by his contemporaries, Richard Avedon and Diane Arbus, and, although they were younger like him, Nan Goldin and Robert Mapplethorpe. “It is complicated, however, a lot of it has to do with him and his personality … there was never a critic or curator who wanted to show Hujar’s work who he did not hang-up on,” says Shultz. He had few substantial solo shows, and unlike his peers, received little press attention. It was only posthumously that Hujar’s work captivated the renown it holds today, and to celebrate that legacy, Pace Gallery and The Peter Hujar Archive will donate 10 per cent of all sales from Cruising Utopia to the NYC AIDS Memorial — a memorial honouring the more than 100,000 New Yorkers who have died of AIDS, as well as providing care for the ill, fighting discrimination, and lobbying for medical research.

Ultimately, Hujar’s rich archive carries historical and contemporary significance: bearing witness to an important period in the ongoing fight for LGBTQ rights and providing a tomb of inspiration for photographer’s working now and in the future: “The diversity of the world that is captured is so powerfully conveyed through these photographs, and that is, I think, what gives them their staying power,” says Shultz.

Peter Hujar: Cruising Utopia is on show in Pace’s online gallery until 28 July 2020.