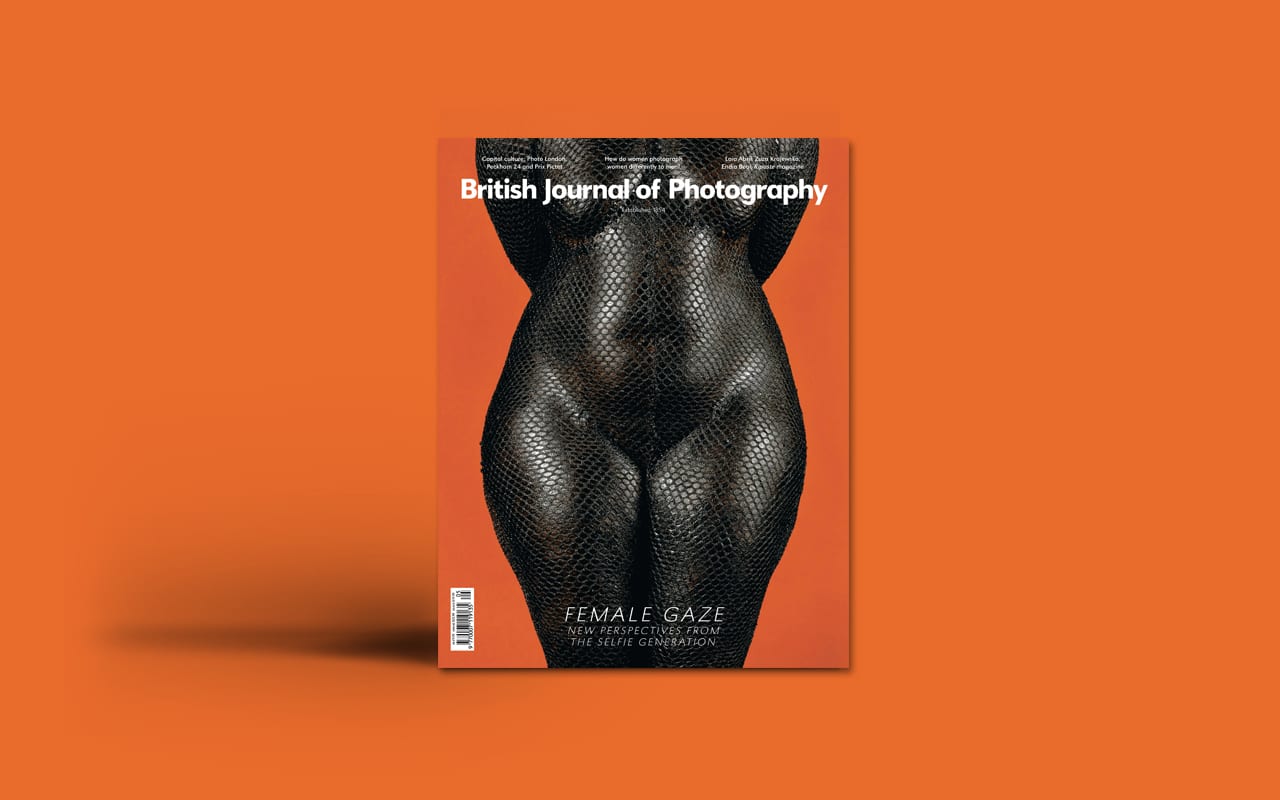

As a gift to our community during the coronavirus lockdown, we are offering our Female Gaze issue as a free digital edition

“Photography is an expression of power,” writes Charlotte Jansen in the May 2017 issue of British Journal of Photography. “The photographic act is often viewed as an assertion of masculine dominance; a predatory point-and-shoot action.”

Jansen argued that social media and the sheer power of the number of women getting behind the camera is changing all that, and affecting how we see things. Though it’s a contentious issue, Jansen confident that the female gaze is different to the male: “They see the world differently – in just as much colour and nuance. We are beginning to see that world, everywhere we look.”

Three years on, the question still remains: is she right? As a free gift to our community during the coronavirus lockdown, we are offering the chance to revisit this hypothesis in a free digital edition, available here.

Included in the issue is Endia Beal’s project Am I What You’re Looking For?, which taps into unwritten codes of the corporate ‘look’, interrogating what it means to look ‘professional’ and the extent to which black women can fit those maxims.

“At Yale University, I found myself in a place of double consciousness,” says Beal, finding herself the only black person in the 2013 cohort for the fine arts MA in photography. “I grew up in one culture and now inhabited another, becoming a mediator between these two worlds.”

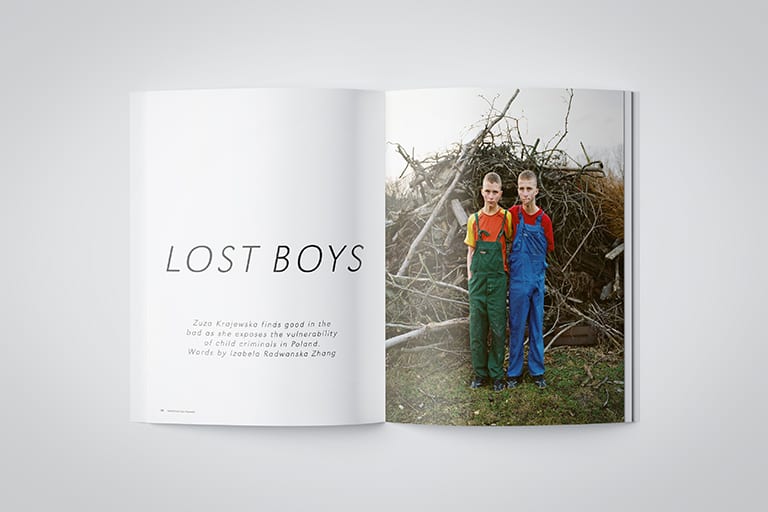

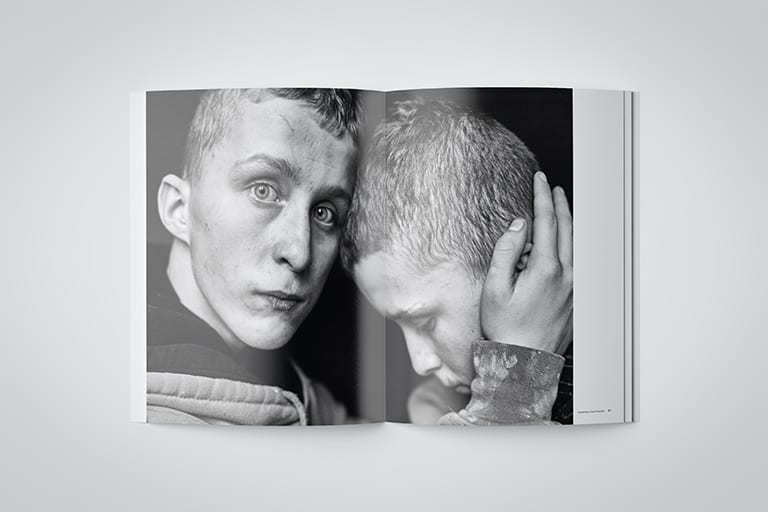

Zuza Krajewska tackled a very different topic for her project Imago, a look at the adolescent boys imprisoned for violent crimes in a youth detention centre in Poland. Spending a year on the project, she got to know the young men well – and says that being a woman helped her do so.

“It’s not that only a woman could have taken these photographs – both a man and a woman could view it under the same gaze if they let themselves,” she explains. “But it was easier for the boys to open themselves up emotionally in front of a woman than in front of a man, who, there at least, they always view as a rival.”

Meanwhile, Laia Abril tackled a contentious subject in the first chapter her ongoing look at misogyny — abortion. In particular, she looks at the repercussions of woman not having access to legal, safe or free access to the procedure – and turning to dangerous, mentally and physically scarring alternatives.

“I’m trying to visualise the history of misogyny so we don’t forget what’s in the past and don’t get too comfortable in the present,” she says. “So we take a look at things that sometimes we don’t want to – in a visual way that doesn’t make you just turn the page but makes you engage somehow and think a little bit.”

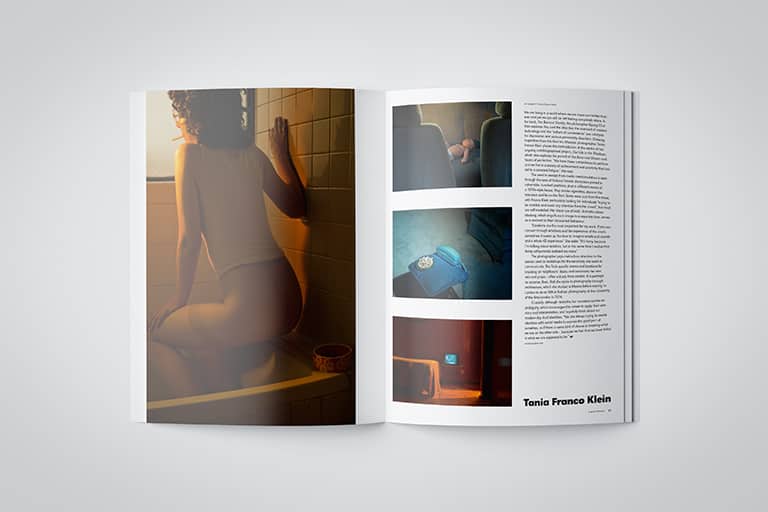

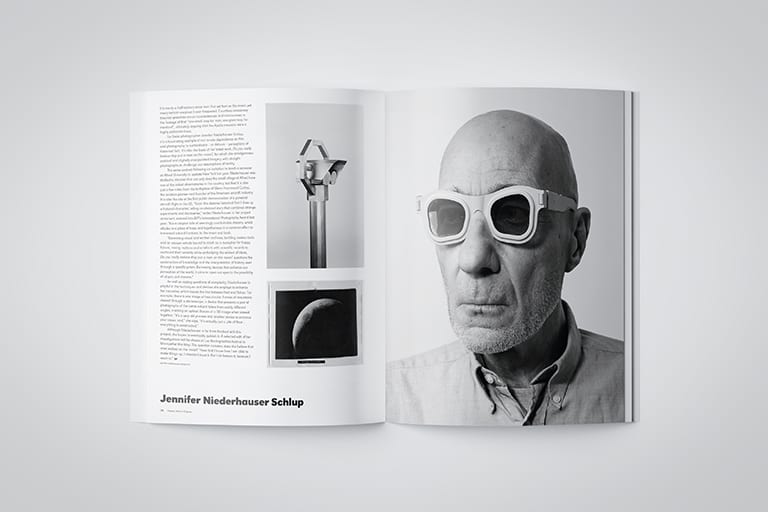

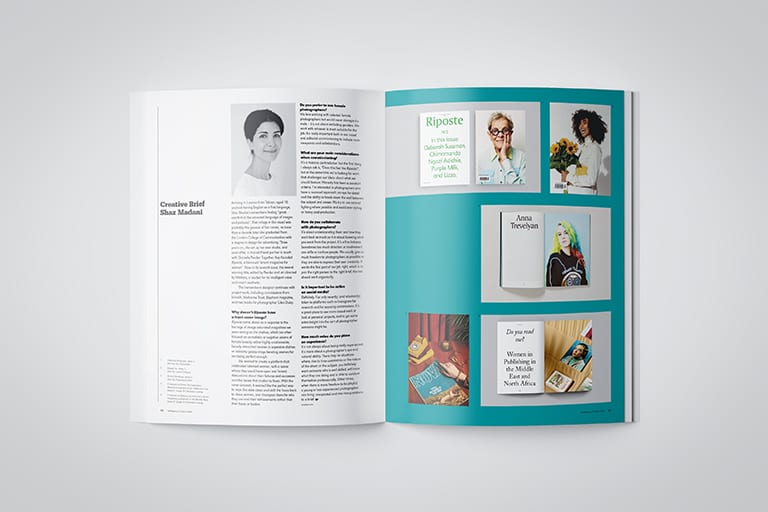

Elsewhere in the issue, we featured projects by Lena Mucha, Tania Franco Klein and Jennifer Niederhause Schlup, and spoke to Riposte art director Shaz Madani about her work on the “smart magazine for women”.