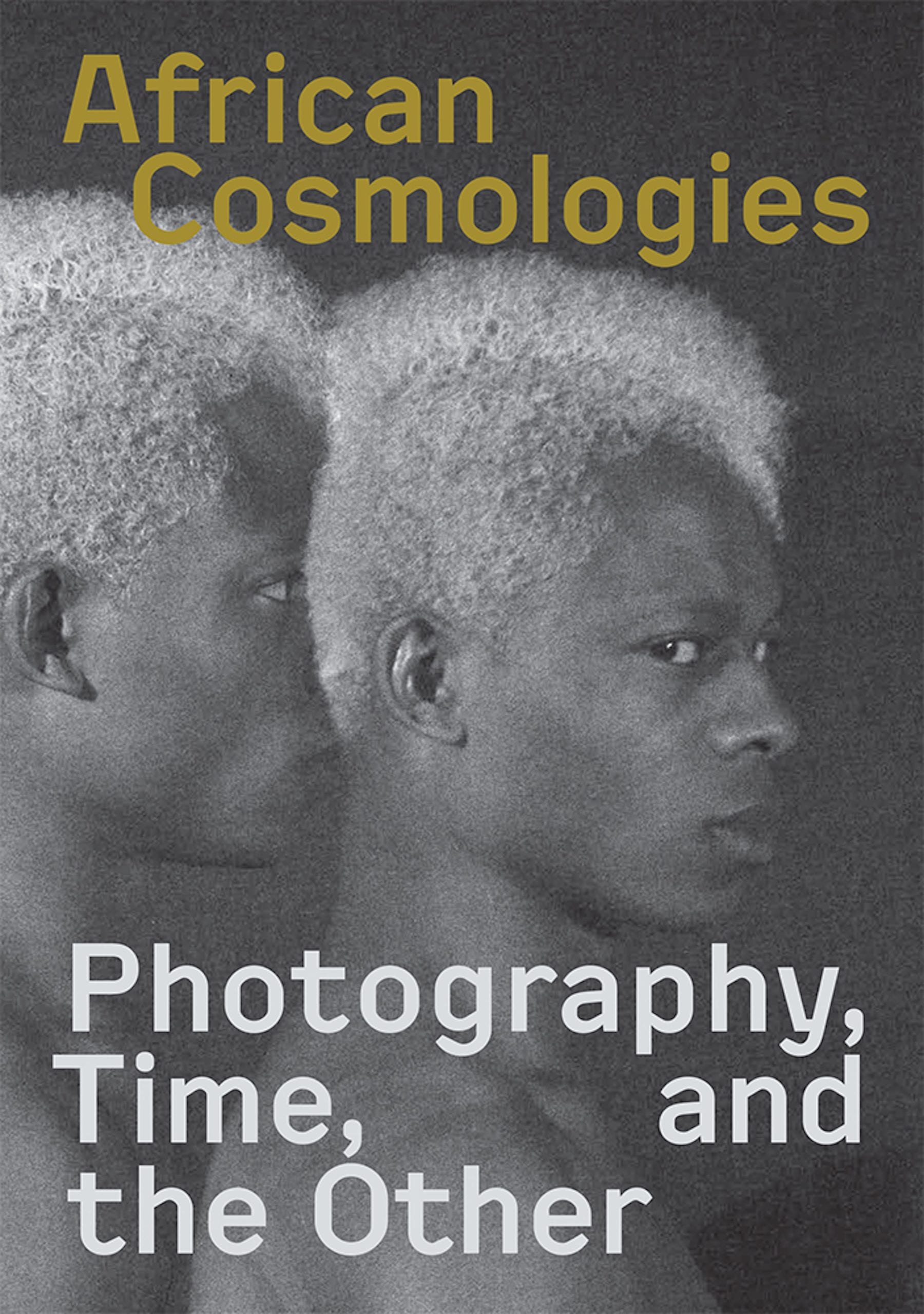

African Cosmologies — Photography, Time, and the Other

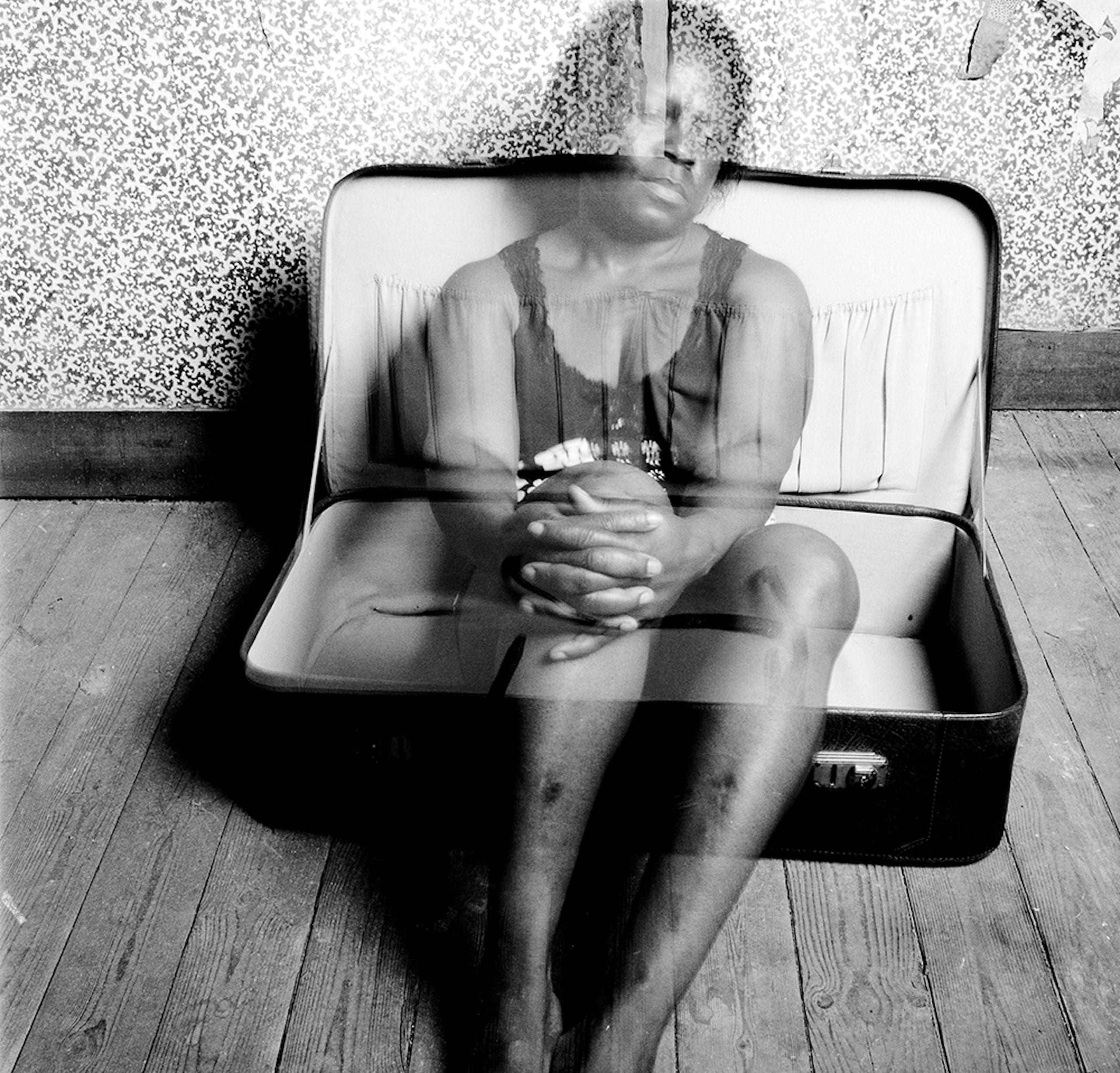

BC1-ND-FC: By and by, I Will Carry this Burden of Hope, till the Laments of my Newborn is Heard #2, 2017. From the series Blazing Century 1, Niger-Delta/Future-Cosmos, 2011–17. © Wilfred Ukpong.

Source: