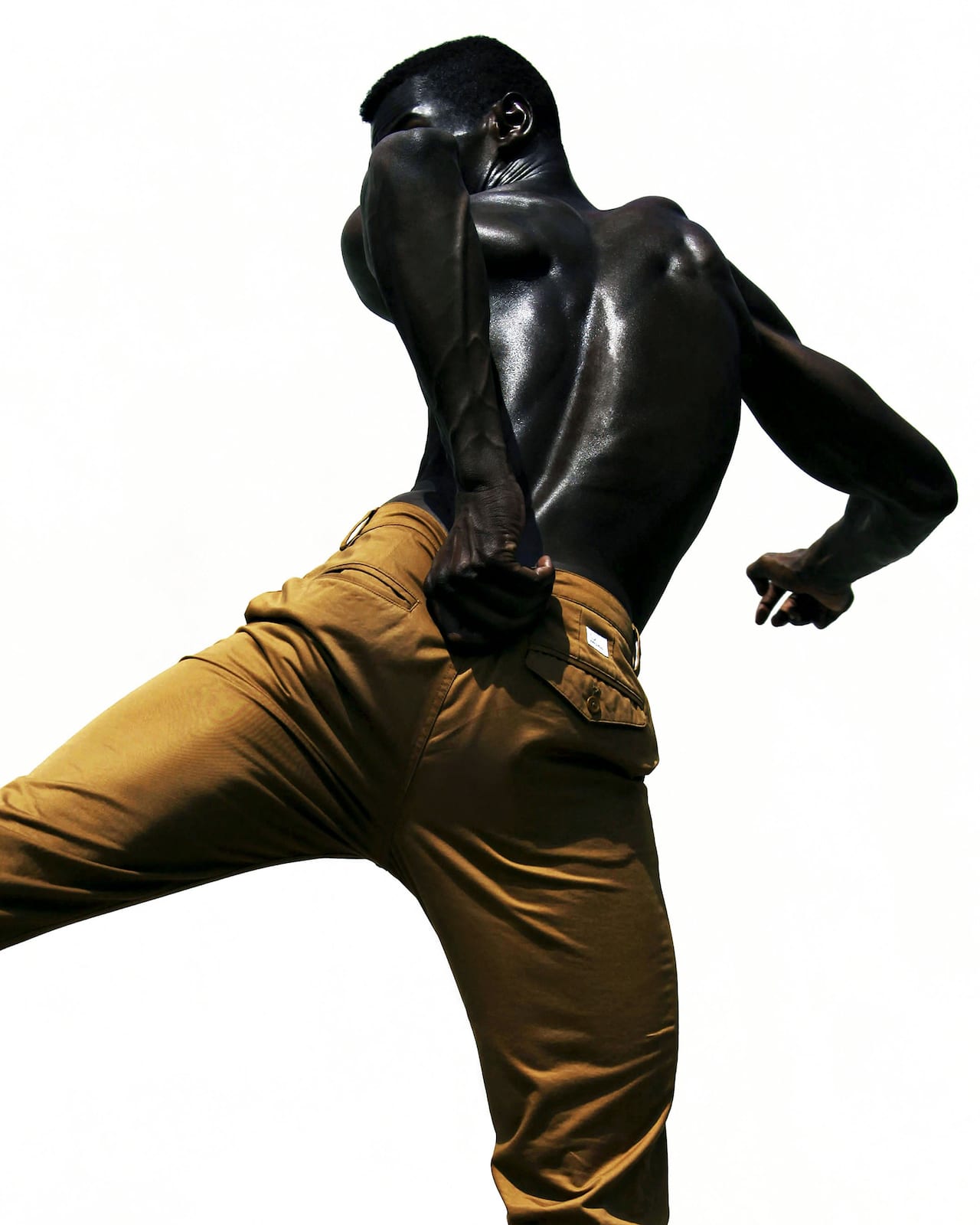

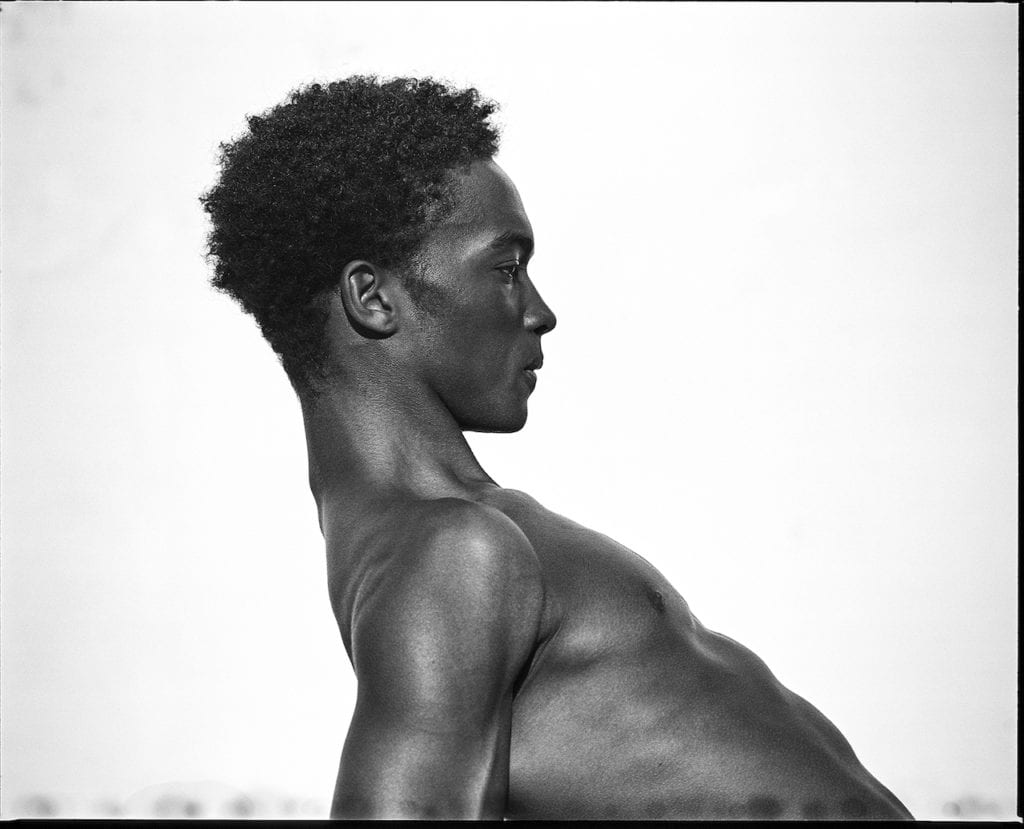

Against the backdrop of a fraught US racial climate, to behold the seminal work of Dana Scruggs — her ode to the beauty of the Black male body — is to witness a soul-stirring reclamation of power and autonomy within her subjects: a deft dismantling of the colonial gaze. The New York-based photographer’s signature handling of light and movement all but transcends the static medium, at once forceful and ethereal, dynamic and delicate. “There’s a fearfulness of Black men in American society and globally,” Scruggs has said. “I wanted to change the narrative.”

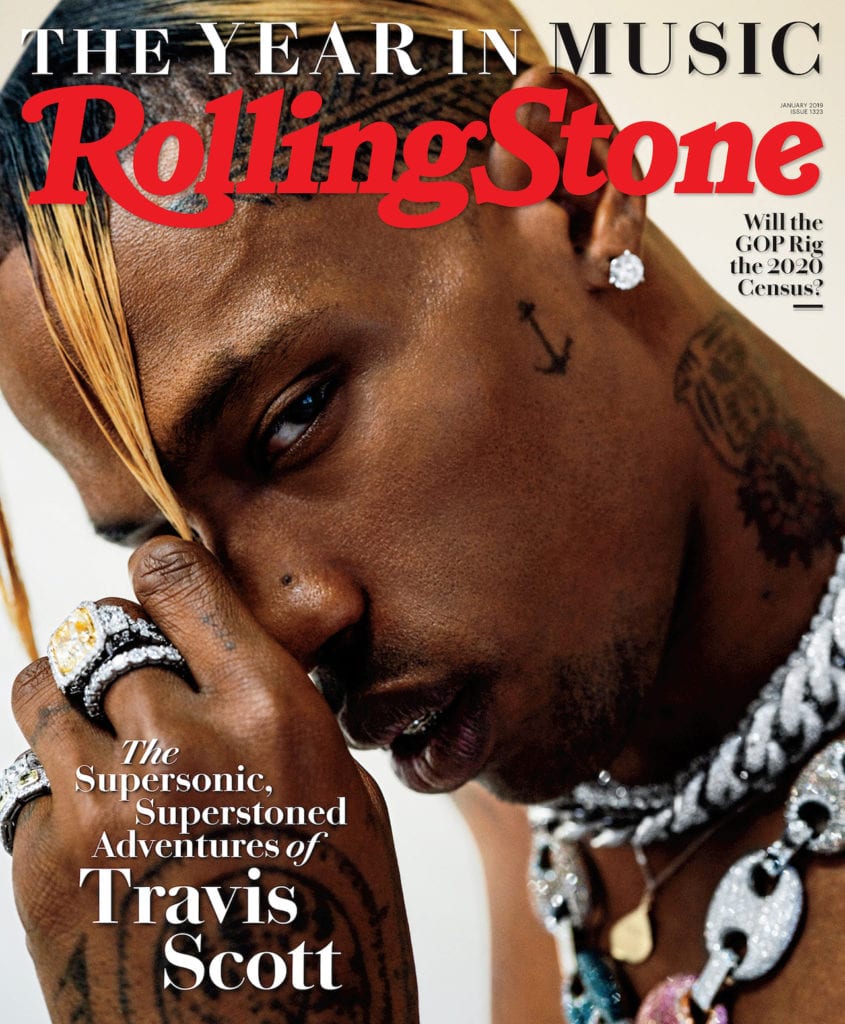

To date, Scruggs’ achievements as a photographer are historic. In 2018 she became the first Black woman to shoot an athlete for ESPN’s The Body Issue; later that year, she became the first Black person to photograph a Rolling Stone cover in the magazine’s fifty year history. She was handpicked by rapper P. Diddy to shoot his 2019 Essence cover and has lent her vision to GQ, the New York Times and beyond. But for Scruggs, shattering the ceiling was far from a straightforward manoeuvre.

“Don’t let the ‘Gram fool you,” the photographer has told her 27,000 Instagram followers. “For most people, it takes a painful amount of sacrifice to even begin to garner success.” Indeed, prior to Scruggs’ ascent, she spent close to seven years self-assigning amidst personal and professional crises. Unable to secure steady work in New York, she crowdfunded to launch SCRUGGS, a print magazine dedicated to her interpretation of the male form. Shooting and writing all the content herself, the first issue became more akin to her personal manifesto, and proved pivotal in the formation of her career.

Today, Scruggs shoots a wide range of commercial and editorial content, continuing to redress myopic depictions of the Black experience in her work. She ardently employs her platform to champion other people of colour in the industry: not simply photographers, but assistants, stylists and wider crew.

To coincide with Female in Focus 2020, British Journal of Photography caught up with Scruggs to talk perseverance, facing criticism, and “making it” in spaces of structural inequality. Crucially, the Chicago-born photographer makes the point that it lies on white industry professionals, and no one else, to educate themselves on the systems in which they are complicit — and to work to dismantle these systems for an authentically equal landscape.

—

Could you tell us how you got into photography?

I went through a period of severe depression — to the point where I couldn’t leave my house. I was living in my hometown of Chicago at the time. In order to pay my rent, I decided to start an Etsy shop to sell all of the vintage clothes and furniture that I’d accumulated in my apartment. But to sell stuff, you need to take photos. During that process, I discovered that I enjoyed photography. I didn’t think about it as a career until agencies started reaching out, asking me to test after seeing photos for my Etsy shop that I’d taken of unsigned models. Within a year I moved to New York to become a photographer full-time, although the ‘full-time’ part didn’t happen for a very long time.

Who are some of the photographers/artists that influenced you?

I love Kerry James Marshall’s work. I recently shot an editorial for Models.com that was my interpretation of some of his paintings. His use of color and light and lack of light while creating these vignettes of the everyday lives of Black people reminds me, so much, of moments in my own life with my family. Black people don’t often get to see ourselves reflected in art — especially art that has been accepted into the mainstream and created by a Black artist. That’s a powerful thing.

The work of Txema Yeste and Herb Ritts have also inspired my interest in creating work that is centered around movement, creating shapes with my subject’s bodies, and generally striving to make strong images. From very early on, that was a big concern of mine. I’ve never wanted to make work that feels passive. I’ve built my aesthetic around my subject being engaged, so that my audience will feel engaged. And most importantly, so that I will feel engaged.

How would you describe your artistic process? And what about your signature style — how has that developed?

My style developed from me shooting constantly. During my first couple of years in New York, I was shooting two to five times per week. Or shooting three or four subjects back to back if I only had one day that week to shoot. You can’t develop your style or grow as a photographer or even expect to maintain an interest in photography as a career if you’re not shooting regularly. At a certain point I was working two jobs, almost everyday, from 9am until midnight. If I had a morning off or could carve out a few hours in the afternoon, I was shooting.

For people that want to make photography their career: if you’re only shooting once a month or once every few months, then you’re not serious about being a photographer. The people that make it are the ones who don’t make excuses about not having time. They make work regardless of whether they have time or not.

SCRUGGS is a project of such beauty. You’ve said yourself that a female photographer shooting men is a rarity. It’s obviously key, too – as you’ve often spoken about – that you’re a Black woman shooting Black men. What informed your choice of subject matter for SCRUGGS?

When I moved to New York, I finally had the opportunity to shoot male models. I’d always wanted to, but Chicago had very limited options. The first time I shot a male model here, I only wanted to shoot men from that moment on — which is what ended up happening. I almost exclusively shot the male form for almost seven years. That’s what I was known for. I had almost zero interest in shooting women unless they were paying me. It’s interesting — and kind of sad — that people don’t associate me anymore with being a Black female photographer who only shoots men. I hadn’t realized how much I tied my identity with that until it was gone.

Since I was only interested in shooting men, it made sense that I would center SCRUGGS around my fascination with men and the male form. Adonis Bosso was the first model I photographed for the magazine. The work that we created together was the strongest that I’d ever made and has informed all of my subsequent work, which focused almost exclusively on the Black male form.

Being a Black woman who’s getting attention from the art world for documenting and creating art with Black men is very important because, historically, white people are given more acclaim, credibility, and funding for making work centered around — and in many cases fetishizing — Black people. Major institutions and galleries have historically ignored Black artists who create work about Black people, because these institutions have a white perspective. Consciously and unconsciously they give the white gaze more validity than the Black gaze — even if the work is mediocre and/or problematic. This is what systematic racism looks like.

You’ve spoken about the kind of criticism you’ve faced after some of these achievements — e.g. the backlash and vitriol from your momentous Rolling Stone gig. Meanwhile, as you’ve discussed, if you critique white power structures, you get called ‘angry’. How do you navigate such a staggering double bind?

When I was bullied on Instagram by a white female photographer — and her friends — after my Rolling Stone cover came out, it was just another example of how many white people constantly feel the need to center themselves when Black people start making room for ourselves in white spaces. It’s racist and it’s offensive and it needs to stop. I was called expletive names by this person. She said that I didn’t get the cover due to any talent, but rather because Rolling Stone gave it to me — so they could finally say they had a Black person shoot the cover. This wasn’t true. I knew when they offered it to me that I was the first. They didn’t know until I asked them to check their archive, after the cover had been shot. I was continuously bombarded with public and private messages from this person lambasting me because I’m one Black woman who got an opportunity that many white people have gotten before. Even after I kept asking her to stop.

I learned a lot from that experience. I learned that I can’t let other people’s uniformed and racist opinions of me and my work affect me. I also realized that due to the exposure I got from the work, I now have a responsibility to shine a light on what Black photographers go through in this industry. My hope is that people in a position to hire will start looking for talented Black people to work with, instead of going with the path of least resistance and hiring the same handful of white photographers over and over again — or realize that they may only be hiring people that look like themselves or run in the same social circles as they do. Which is another reason why Black people are isolated from success in this industry.

Just because a small number of Black photographers have become more visibly successful doesn’t mean that diversity in hiring is no longer an issue. As a matter of fact, nine times out of ten, if I didn’t hire Black assistants or suggest Black stylists and makeup artists, then I would be the only Black person on most of my sets. I’m not going to be a monolith in this industry. I’m bringing other Black people up with me.

While it’s true that we’re gradually starting to see change in the industry (i.e. more women than ever before in gatekeeper positions), it’s also true that these are predominantly white women. You’ve spoken in the past about an experience with a white female photo director during which you had to defend your approach to capturing Black narratives. How can white women in the industry be better allies to Black women photographers as we fight for a more representative landscape?

Most of the people who’ve hired me are white women. They are the industry’s gatekeepers. For the most part, I’ve worked with white women who’ve been helpful and collaborative and who see me as an equal. There have been a handful of occasions where that hasn’t been the case — particularly them seeing me, a Black woman, as an equal. A big part of that comes from many white women rarely working with a Black woman (or a Black person for that matter) who’s in a leadership position. So when I assert my opinions or my autonomy, some white women see you as being angry or aggressive. Whereas if I were a white woman, they would see me as being thoughtful and assertive.

Even the act of saying “no” to a white woman can get you labeled as difficult, or they might not hire you again, or they might unfollow you on Instagram. And I’m talking about simply saying “no” to a job offer or saying “no” when they want to use your work in ways that you feel uncomfortable with — and that they have no legal right to use in those ways. With these kinds of women, it’s like, once you say “no”, their automatic reaction is, “how dare you say no to me?” Most of them will deny, even to themselves, that their incredulousness comes from a place of white supremacy. Like I’ve often said, you don’t have to be a white supremacist to uphold white supremacy.

The word allies has been overused and underutilized in action. You shouldn’t need a title for you to say, “I’m not like those other white people”. Your actions showing that should be enough. What white women can do to not be racist or uphold racist ideals is to not be offended and belittling when a Black woman doesn’t do what you want her to do. And since white women are the gatekeepers, they should seek out and hire talented Black creatives. While they’re doing both of those things, they should use Google and the library to research how to not be racist. White people asking Black people to tell them how to not be racist is labor and exhausting and can be traumatizing. There’s plenty of information out there. Now is the time for white people to do their own work.

Do you feel hopeful about the direction the industry is headed in?

I do feel hopeful, but I also see there’s still a lot of work to be done by white gatekeepers in this industry. When I see my incredibly talented Black friends depressed and on the verge of giving up because they can’t get steady work, it’s heartbreaking. And for almost seven years, I was one of them. There are a few of us who are “making it” — but we’re the exception, not the rule.

What advice would you give to someone who’s looking to overcome obstacles brought by their race or gender in the photography industry?

I would say don’t depend on other people to give you opportunities or assisting gigs or even advice. If you’re constantly waiting on other people to help you, you’ll never move forward. I learned most of my technical skills on YouTube, I never assisted, and I never had a mentor. This happened because I was usually the only Black woman working (and working for free for that matter) in photographic spaces that were dominated by white men. They weren’t interested in connecting with me and were only interested in helping each other. I’ve definitely had help along the way — but that came after I started helping myself by creating a body of work.

It’s also important to make work that you’re excited about and that’s meaningful to you. If you’re still trying to figure out what kind of work that is — you need to be shooting more. It takes time and effort. Lastly, don’t worry about what everyone else is shooting or what’s “in fashion”. If your work looks different or “other”, that’s fantastic. The same people who told me I wouldn’t make any money or get big jobs because I was only shooting Black men are literally eating their words.

If you’re a photographer impacted by the Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, get 99% off 1854 Access Membership. That’s 7+ years of British Journal of Photography digital archive, free entry to Female in Focus (and all of our awards), plus paid commission opportunities once this crisis is over — all for just £1.