On 11 March 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the Pacific coast of Japan unleashed a tsunami that roared through the country’s Tōhoku region, devastating its northeastern coast and killing around 20,000 people. At Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant, the waves unleashed another menace: a level seven nuclear meltdown — the world’s largest disaster since Chernobyl.

Due to concerns over the effects of radiation exposure, the government established a 30-km exclusion zone, evacuating 160,000 people. Today, almost nine years since the tragedy, roughly 50,000 people are still displaced, but there are signs of recovery. Communities further away from the power plant have been restored, rail services and roads have reopened, and, in 2017, the government began to financially incentivise residents to move back to their hometowns.

The news caught the attention of British photographer Giles Price, who was looking to document the construction of the 2020 Summer Olympics, following on from previous projects made in Rio and London. In the 2020 games, Fukushima will host one Olympic baseball match and six softball games, and on 26 March, the football stadium J-Village will initiate the Olympic torch relay. The organisers hope that the events will help to recover the region, not only from the physical and economic devastation but from the stigma that can be attached to an area affected by disaster and radiation.

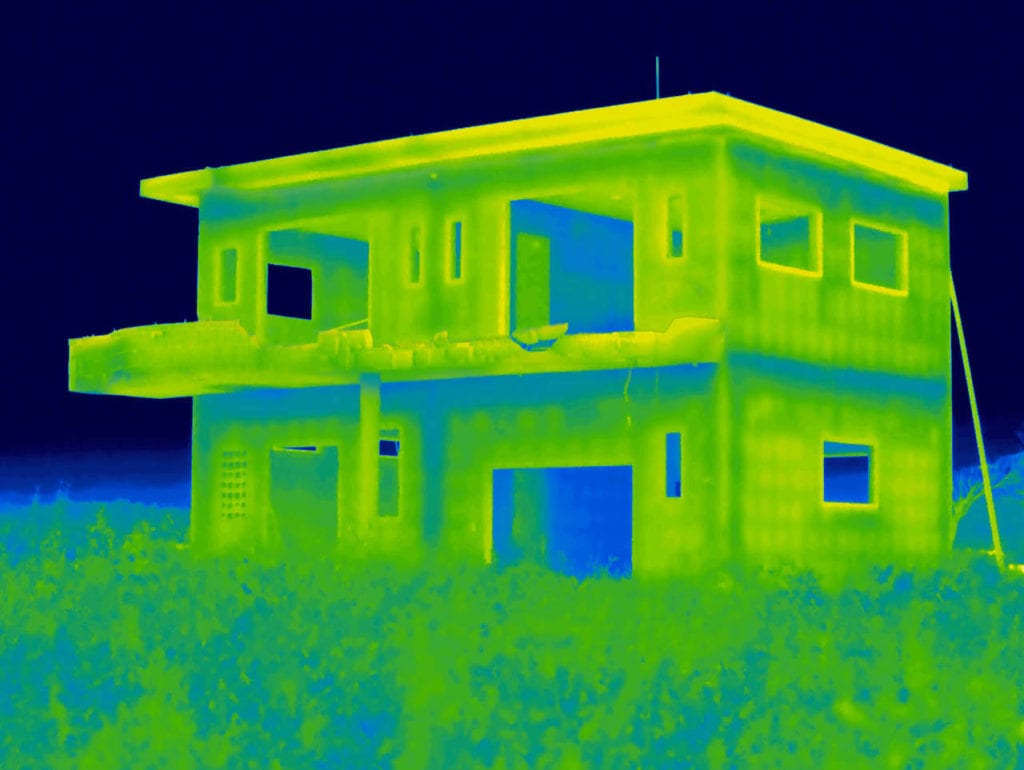

It was these invisible effects of the crisis, like the stigma surrounding radiation, that concerned Price while producing his latest book, Restricted Residence, a series of thermal images shot in Namie and Iitate: two towns that are now beginning to recover after eight years of desertion. Namie, just 10km northwest of the power plant, once had a population of over 20,000, and Iitate, a further 40km away, had 6,000 residents. Although the Japanese government ceased restrictions in April 2017, many former residents are reluctant to return, and both villages currently have only 5 per cent — around 1,000 and a few hundred respectively — of their original populations.

Price’s book includes an intriguing essay by Fred Pearce, in which the science and environmental writer introduces the term radiophobia. “Something about the invisibility of radiation, and its potential to kill silently, brings on [this] condition among many of us,” writes Pearce. “We have good reason to fear what we cannot see, or taste, or hear, or touch. If our senses offer no guide to the scale of the risk, we must assume the best or fear the worst.”

Despite the level of fear that arose from the nuclear fallout, Price asserts that in Fukushima, there have been no direct deaths from the radiation itself — with the possible exception of one plant worker who died of leukaemia shortly after the accident. The biggest cause of death was the evacuation process — around 60 elderly people died as they were rushed out of care homes and hospitals — and a surge in suicides that followed an epidemic of post-traumatic stress.

“People’s lives were uprooted overnight, livelihoods were lost, families were split up and relocated to other areas,” says Price. “The long-term health issues have turned out to be more to do with mental health.”

Over two visits to Fukushima in 2017 and 2018, Price was eager to capture how the environment had changed, both visually and non-visually. The journey there involved driving down Japan’s newly reopened National Highway 114, a major highway that connects Fukushima city in the west with coastal towns like Namie in the east. “It is the most intense fallout area, and you’re not allowed to stop the whole way,” says Price, who was instructed to keep his windows rolled up, keeping an eye on his Geiger counter, which rose and fell as it hit occasional hot spots of radiation.

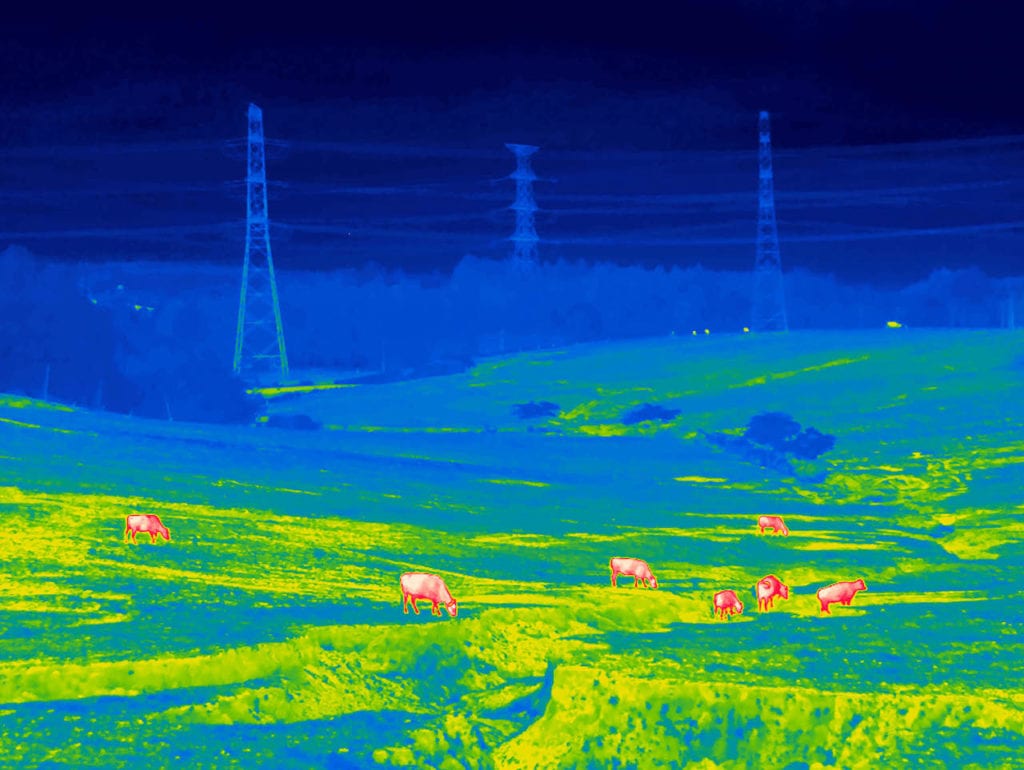

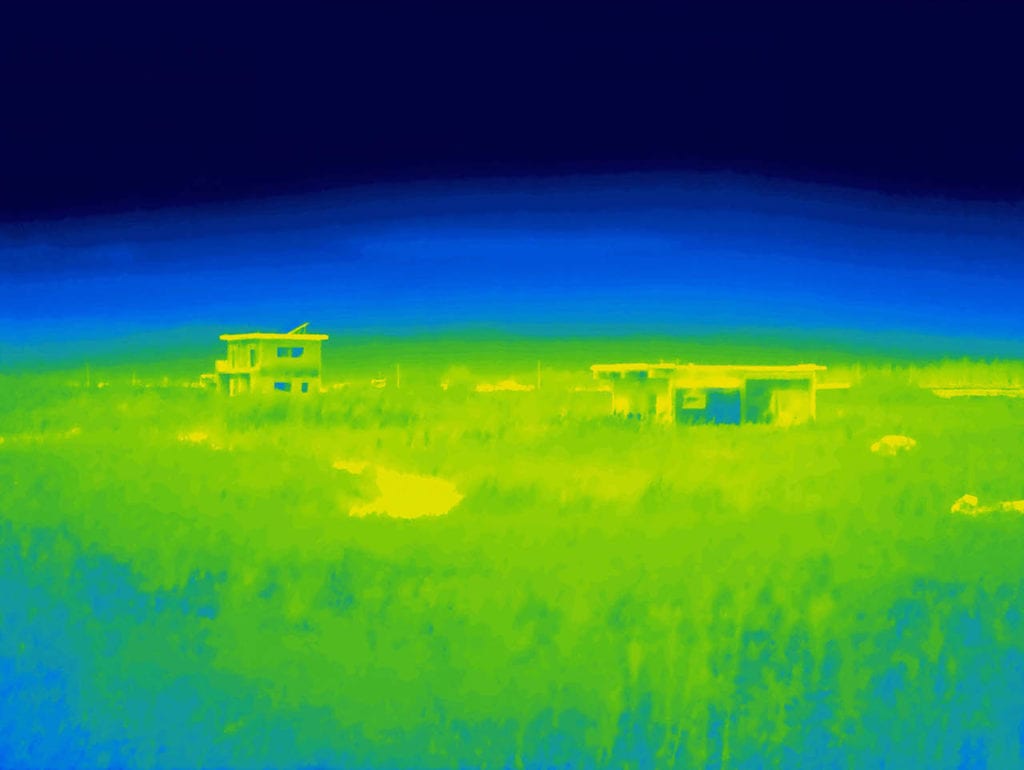

Initially, Price intended to produce diptychs: a thermal image followed by a “normal” shot of the same scene. But in the editing process, he found that there was an intensity to the thermal images that became more engaging than a static approach. “My images are not scientific, they are purely visual, but there is a conceptual link,” he explains. Thermal imaging is used to detect certain illnesses and cancers, and there is also an element of anonymity that it brings to work. This ties in with the cultural backdrop of the stigmatisation associated with radiation, as well as allowing for Price to instigate a wider conversation about non-tangible issues such as stress and mental health.

“A lot of my work revolves around thinking about how we can visually retell a narrative,” says Price. “There has been great work made in and about Fukushima in the last eight years, but to visually appropriate it in the same format is perhaps not going to engage people.”

Designed and edited by publishers Loose Joints, the book follows a circular sequence. We enter and exit through still landscapes of cold blues and greens, where leaves swallow abandoned cars and structures that remain unrepaired. Approaching the centrefold, hues of red and orange begin to fill the frame as we meet clean-up and reconstruction workers, a taxi driver, and residents who hope for a better future.

As the 2020 Olympic Games approach, Price’s book encourages viewers to rethink their own perception about environments affected by tragedy. “We all have to be aware and talk about these issues,” he says. “These images also show human resilience, and raises questions about the wider ramifications of how people live with environmental disasters everywhere.”

Restricted Residence by Giles Price is published by Loose Joints. The book launch will be taking place on 16 January at The Photographer’s Gallery bookshop, from 6 to 8pm.

—