—

With the untimely passing of Michael Putland, we are indebted to the legacy he leaves behind, but his wonderful body of work does not do true justice to the man himself. I was fortunate to have known Michael for a number of years and though it may be a cliché, he was one of the only true gentlemen in the often cut and thrust world of music photography. He was kind, thoughtful, funny and always truly humble. In short, Michael was a wonderful human being whose positivity was only equalled by his passion for photography.

A regular visitor to the Getty Images archives, where much of his work is stored, Michael never failed to bring with him a box of cupcakes for the archival team. His genuine appreciation of the work we do and his complete lack of ego made him a very firm favourite here.

Michael’s recent book — The Music I Saw — is a fitting testament to his craft over six decades, and he never failed to acknowledge the great part that fellow music photographer and future business partner, David Redfern, played in developing his career. David and Michael’s paths crossed many times while covering gigs in London during the mid-to-late-1960’s, and the pair became firm friends, initially through their mutual love of jazz.

It was David who, after making the initial connections with the BBC Press Office, helped Michael gain access to the hallowed ground that was BBC Television Centre and ultimately to Top of the Pops and The Old Grey Whistle Test. In those days access to the stars was considerably easier than it is today, and Michael’s charm and impeccable manners enabled him to connect with the many of the musicians who have provided the soundtrack to our lives.

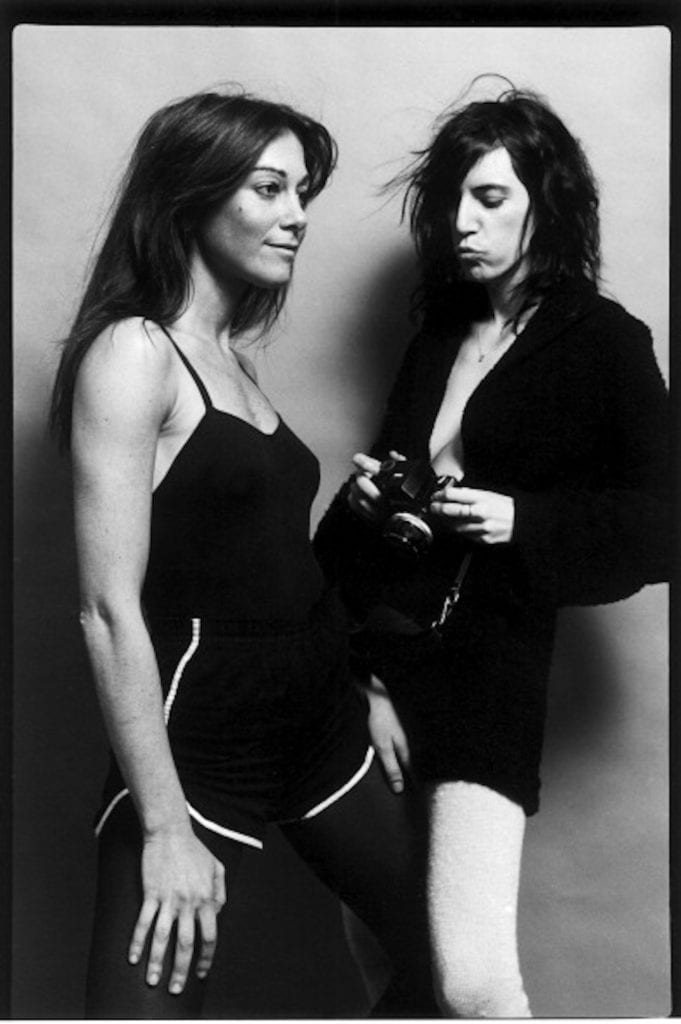

Michael innately understood that music is both an aural and visual experience and his pictures responded to the individual style of each artist he photographed, illustrating something of the music they collectively made through light, shade and colour.

Setting up his own agency Retna, New York, in 1977 enabled Michael to expand his skillset further – his energy, expertise and support for his fellow photographers was considerable – but his true calling was always the camera. He admitted to me that running a business was never part of the grand plan, so he was relieved to return solely to his first love, albeit some 30 years later than he had expected.

It should also be noted that over and above his ability with a camera, Michael was a hugely talented darkroom printer and his prints say much about his sensitivity to the medium. As he said himself, he never had a day off in the 1970s and his work ethic was legendary.

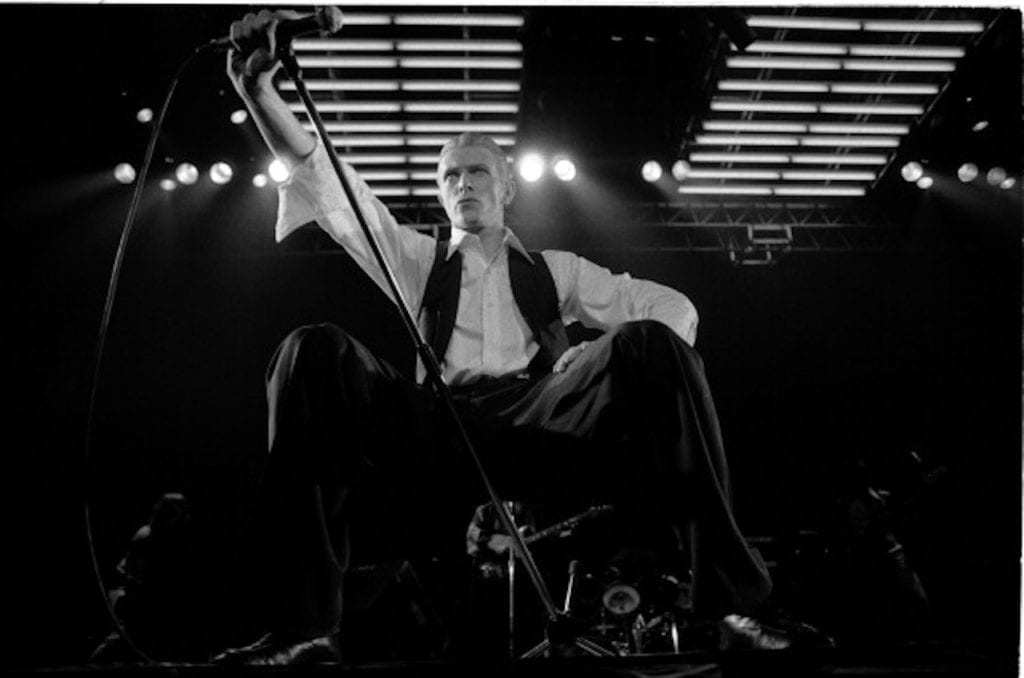

Whether covered in foam (and nearly suffocating as a result) for the Rolling Stone’s It’s Only Rock’n’Roll video shoot, or simply knocking on David Bowie’s door while he was decorating his home in Beckenham (in full Bowie regalia, paintbrush in hand), Michael was at ease with the great and good.

He developed relationships with many of the stars he shot over the years, not least Bowie whom Michael shot in 1973 at the first concert on the fabled Ziggy Stardust tour at Borough Assembly Hall in Aylesbury. There will be many in the photography business who will mourn Michael’s passing but there will be many more again who will hugely miss the man himself – unassuming, modest, always full of enthusiasm and a real passion for life.

I will never forget the look on his face when I was in New York on a business trip not long ago. I was told Michael was hosting an exhibition nearby, and on arrival tapped him on the shoulder and told him I’d flown specially from the UK to pay homage to the man and his work – he positively beamed and continued to do so even though I explained it was actually by sheer chance I was in town.

Needless to say, I will always remember that smile, that warmth, and ultimately the man behind the lens. At the comparatively young age of 72, Michael has gone to that great darkroom in the sky before his time, but the work he leaves behind will always ensure his legacy endures.

— Matthew Butson, vice president at the Getty Images Hulton Archive.

—