Robert Frank’s The Americans greatly influenced the course of 20th and 21st-century photography. His contemporaries, and those who followed, reflect on the enduring significance of his work

Robert Frank, the influential photographer known for capturing the hardships of everyday life, died on Monday, aged 94, in Nova Scotia, Canada. He is perhaps best known for his seminal photobook The Americans, which left an indelible mark on the generations of photographers who followed. The project was unique in its refusal to romanticise. It captured the poverty and suffering of post-war America with unprecedented candidness, revealing a country ravaged by poverty, racism and the rise of consumerist culture.

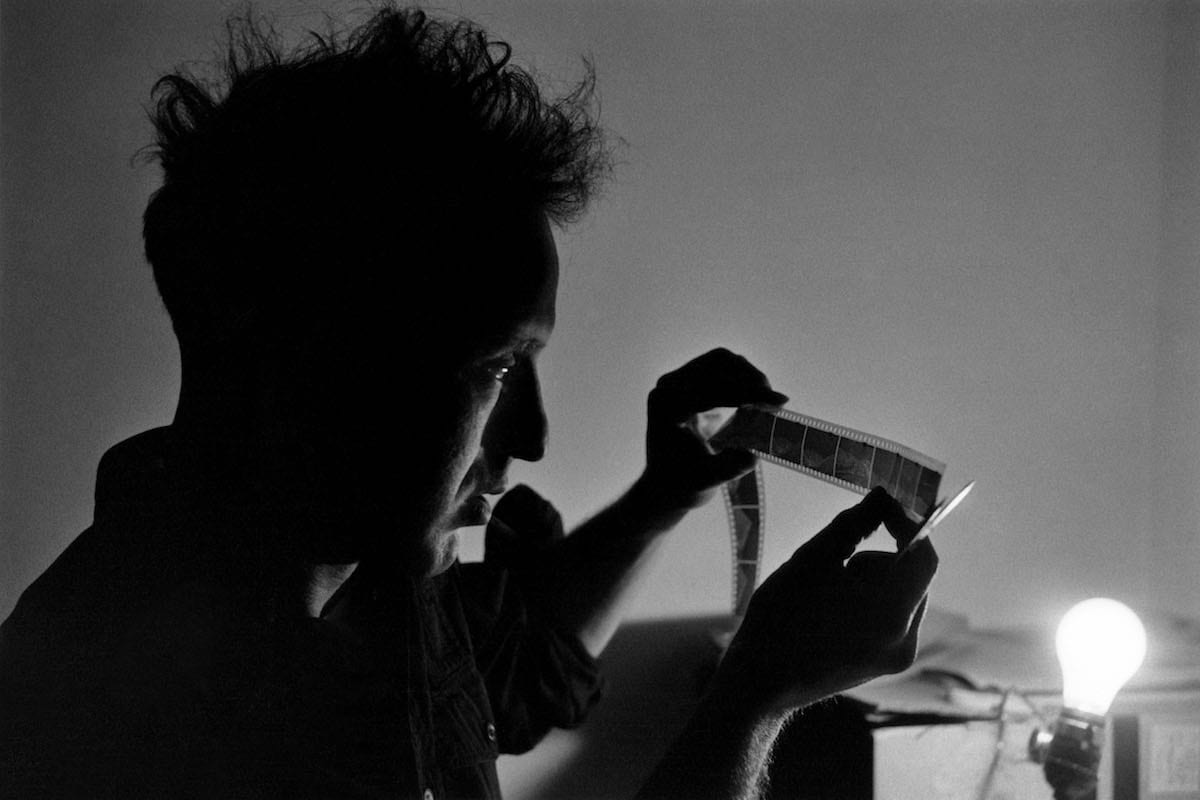

Frank was born in Switzerland on 09 November 1924 and immigrated to New York aged 23. In 1955, he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship and embarked on several road trips across the US, occasionally accompanied by his first wife, the visual artist Mary Frank, and their two children, Pablo and Andrea. Frank’s 10,000-mile road trip spanned 26 states. He shot a total of 767 rolls of film; over the course of a year, 27,000 images would be annotated, tacked to walls, ripped apart, grouped together, and eventually sequenced into a series of 83 photographs, which formed The Americans.

The book was initially released in France, in 1958, by the influential art publisher Robert Delpire; a year later, it came out in the US with an introduction by American novelist Jack Kerouac. The Americans was, and continues to be, iconic, capturing the country with unprecedented directness. Its rough and unconventional approach shaped the trajectory of 20th-century photography.

Frank strongly believed that great artists should never repeat themselves. In the sixties and seventies, he experimented with the moving image and established himself as an avant-garde filmmaker. His controversial documentary Cocksucker Blues charts the Rolling Stones’ 1972 tour of America with unfiltered candor — drug-taking, group sex, and endless backstage parties. As with The Americans, Frank refused to whitewash what he witnessed. The Stones were shocked and sought an injunction preventing its release. Eventually, it was agreed that the film would be shown only four times a year, with Frank present at each screening.

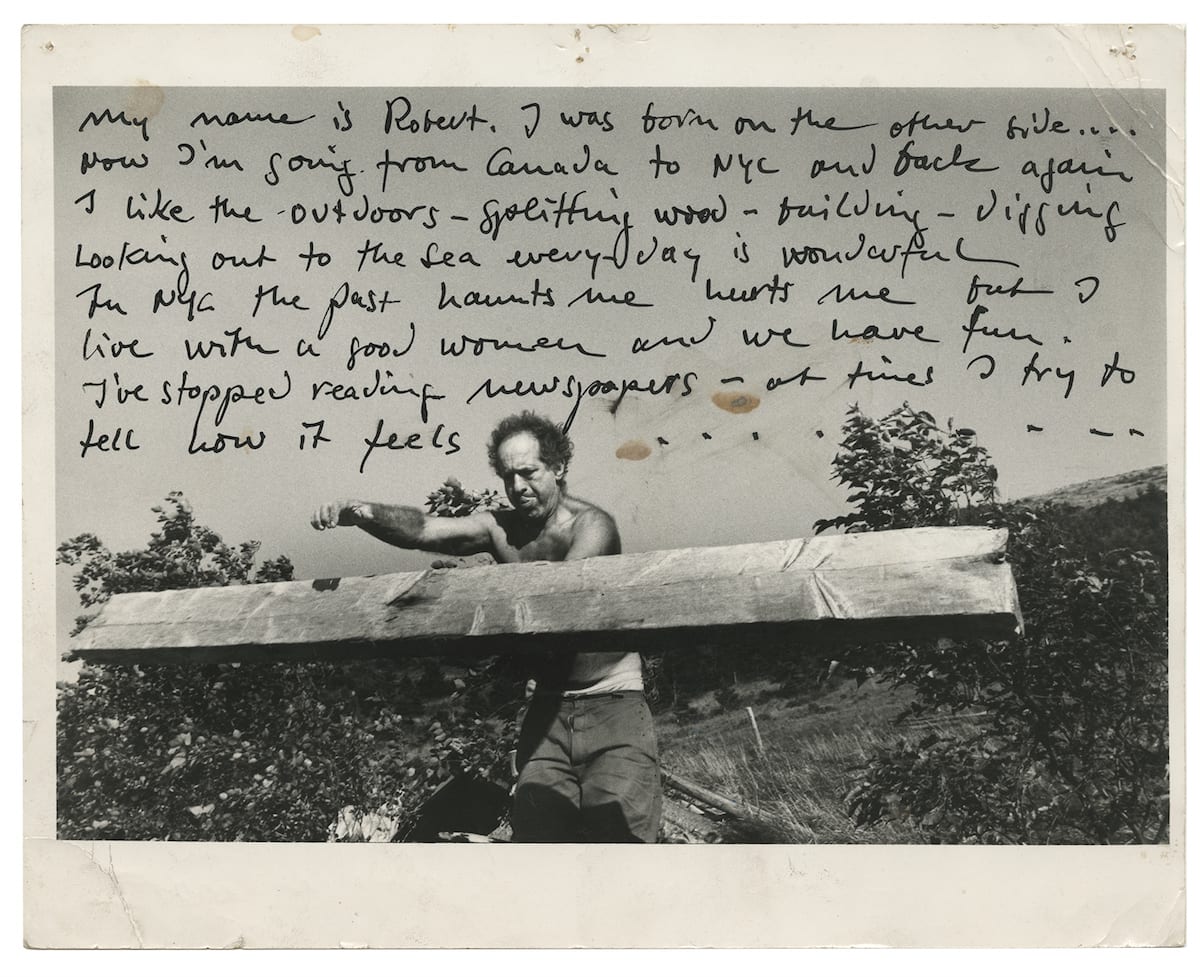

Frank had two children with his first wife; both are now deceased. He moved to Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1971, with his second wife June Leaf, who survives him.

Below, four photographers reflect on Frank’s prodigious contribution to photography and the enduring significance of his work.

Jim Goldberg

The curator Philip Brookman introduced Jim Goldberg to Robert Frank 42-years-ago when they were both featured in an exhibition he was curating. Goldberg was working on his series Rich and Poor, and Frank was a great advocate. “Robert was constantly pushing the boundaries of what an image could be and I tried to adopt that approach as well,” says Goldberg, who developed a close friendship with the photographer. Based on opposite sides of the US, the two communicated regularly by post.

“What led me to appreciate his work the most was his kinship with imperfection. Something could be out-of-focus, but it had the ability to make you feel closer to the subject, the situation. Those ‘mistakes’, which he included in The Americans, opened new doors for viewers to take, new places to look out to or look into. I appreciated those possibilities of how one could grow into imaging the world.

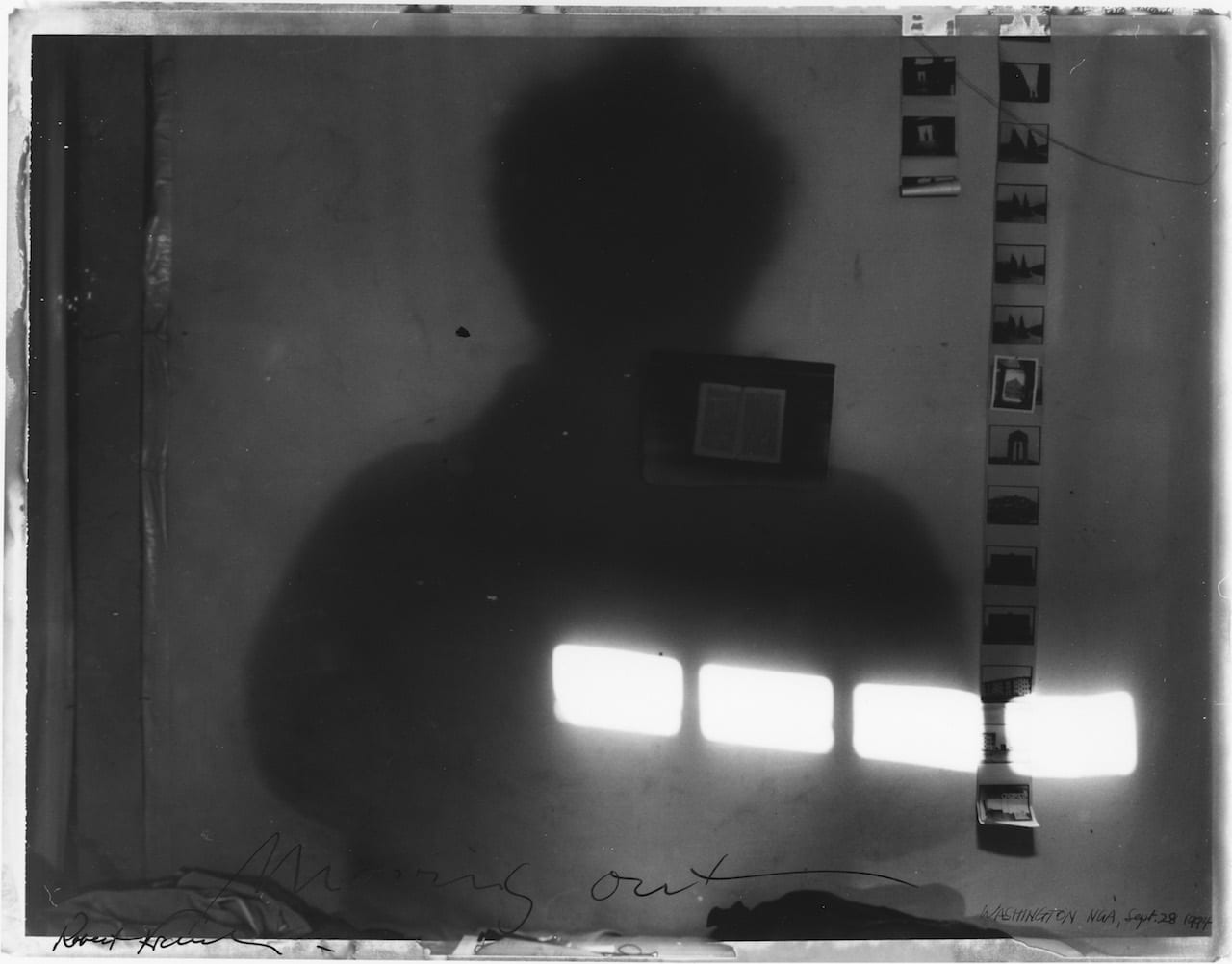

“The work that I’ve kept going back to throughout my career is The Lines of My Hand. Robert got more poetic and I grew more attached to his words and use of visual language. He was brilliant when speaking about photography, about photographs within photographs, about mundane moments, in his titles and stories.

“For all his travelling, Robert was a shy and private person. During his last few years on Bleecker Street, he would often sit outside his house and quietly watch the world go by. When it got more difficult for him to go up and down the stairs, he placed cameras, pictures, postcards, and books in different places in his home to continue to catch glimpses of surprise in every corner. In this way, he kept his mind sharp and his interest in the world strong.

“I will admire and miss him always.”

Martin Parr

“The Americans was the first photography book I ever bought,” remembers Martin Parr. “After that, I bought another 13,000. But, somehow, the first one was never beaten. It is probably the greatest photo essay ever produced and as such is a touchstone for all photographers.”

Parr purchased the second US edition after seeing a selection of images in Creative Camera, a British magazine that folded in the early 2000s. “They showed me what was possible,” he says.

Thomas Hoepker

In 1963, Magnum photographer Thomas Hoepker embarked on his first extensive road trip assignment across the US, for the German magazine Kirstall. “I had one major guiding star: Robert Frank and his book Les Americains,” says Hoepker, who was deeply moved by the publication when he saw the French edition in a bookshop in Hamburg. “At that time, no publisher in America would touch Frank’s dark and brooding pictures.

“I got quite excited when we drove out West and saw that we were near the town of Butte, Montana, on my map. Frank’s pictures from Butte had stuck in my mind and I just had to go there — quite foolishly, but worthwhile nevertheless. Butte was also good to me and gave me some decent images.

“Robert — I’m standing on your shoulders, but I can’t even reach up to your belt!”

Matt Stuart

“My father introduced me to photography, giving me two books, one by Henri Cartier-Bresson and one by Robert Frank,” says street photographer Matt Stuart. “My life changed from that point forever. My father had effectively introduced me to the Beatles and The Rolling Stones in one hit.”