Benedict Redgrove’s earliest childhood memory is of a black-and-white television set showing footage of an astronaut walking on the moon. “I spent my whole childhood loving sci-fi, space, and rockets,” says the British photographer, who has been working on an ambitious nine-year-long project producing over 200 images of NASA’s most iconic objects and spaces. “This project originated from the enormous sense of awe and reverence that I feel towards these objects,” he says.

Now, after nine years of negotiating access, forming relationships, and intense research and investigation, Redgrove hopes to publish the images in a book, accompanied by an “experiential exhibition” in London. The photographer recently launched a Kickstarter campaign, on 20 July – the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing – with a view to have the book ready by November 2019.

Born in 1969 near Reading, England, Redgrove is a graphic designer by trade, and has spent his career “obsessing” over technology and innovation. As a photographer, he cut his teeth in the commercial sphere, shooting campaigns and editorials for clients such as BMW, Audi, Aston Martin, British Airways, but also IBM, Sky, Sony and T-Mobile. BJP first met the photographer when we featured his work, Air Cargo – The Giants of the Sky, in our January 2017 Cool and Noteworthy issue. He spoke about the project that would follow – a series on NASA, titled Past and Present Dreams of the Future.

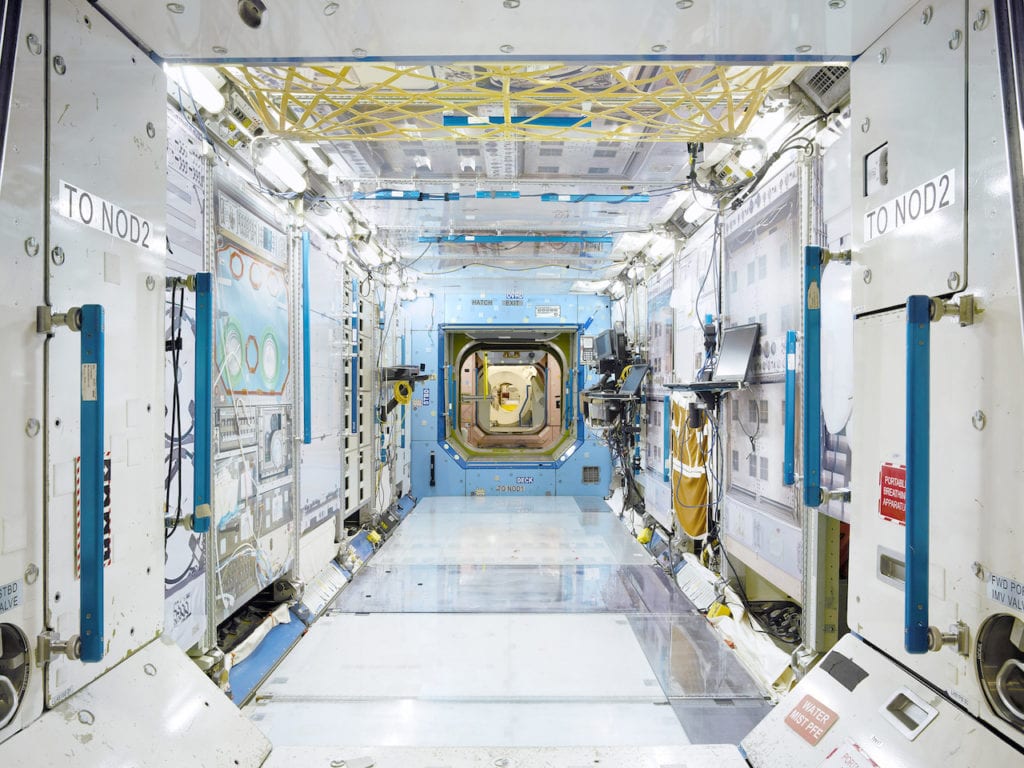

Gaining access to NASA was not easy. The first five years of the project involved finding the right people to speak to, gaining permissions, and locating the objects and spaces he wanted to photograph, such as moon rock collected on Apollo missions, or the assembly rooms where new models of spacecrafts were being constructed. Many of the 200 images came from walking around the facilities and spotting objects through the glass of locked cabinets, like the stamps that were used to label each astronaut’s belongings.

“The objects are symbols of all the things that are great in humanity: learning, exploration, and wanting to better ourselves”

Redgrove recalls the moment he came face-to-face with the last shuttle in space, Atlantis, which has orbited the Earth a total of 4,848 times. “I watched the launch of the first shuttle mission in 1981, when I was 11,” he says. “If that is what meeting a celebrity is like for some people, I understand why they can get tongue tied or shake – that’s how I felt when I saw the Atlantis.”

Redgrove was also particularly moved by the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) jetpack – the equipment that enabled Bruce McCandless II to walk in space untethered, and produce one of the most iconic images ever made in space – and Hasselblad’s lunar camera. “That really blew me away – I nearly cried,” says Redgrove, recalling the moment he opened up the back of it to reveal the cross lines that appear on the first ever photographs made on the moon.

“If that is what meeting a celebrity is like for some people, I understand why they can get tongue tied or shake – that’s how I felt when I saw the Atlantis”

The 200 images that will be included in the book were shot using some of the most advanced camera gear, including the Hasselblad 503CW and the Phase One IQ3, to enable Redgrove to capture as much fine detail as possible. One of the main reasons why Redgrove shot in “super-high-res” was so that he could print the images in large sizes for exhibition. For example, his image of the spacesuit will stand six feet and 11 inches tall, like a “god-like figure”. “A spacesuit is more than just a suit,” he says. “For me it represents the joining of man and machine. Together, they become something greater than each other. The suit gives the man the chance to explore and breathe, and the man gives the suit life.”

While smaller objects were shot against a white backdrop, larger machines and vehicles required a lengthy post-production process. Redgrove used photoshop to retouch and remove the object from the background, adding in the shadows afterwards through using reference images.

“Together, they become something greater than each other. The suit gives the man the chance to explore and breathe, and the man gives the suit life.”

“I’m a little bit on the spectrum, so if I’m in a loud space with too many things going on, it becomes an information overload,” Redgrove explains. “I tend to see things as a located object on its own. I want to locate the thing that is important and remove things that aren’t.”

The photographer likens his visual style to architectural drawings, in which buildings are often presented in solitude. When Redgrove used to work on film, he was conscious about the framing and composition, but now, with digital advancements, he can “create an image that is more like how I see things”.

Discovering the stories and history of each of the objects in Redgrove’s project is fascinating. “As much as it was a lot of work, I feel extremely privileged that they trusted me enough to let me do it,” says Redgrove. “The objects are symbols of all the things that are great in humanity: learning, exploration, and wanting to better ourselves.”

Benedict Redgrove is currently raising funds on Kickstarter to self-publish NASA – Past and Present Dreams of the Future