“A festival is about taking risks,” says Louise Clements, founder and director of Format International Photography Festival, which returns this year to celebrate its ninth edition. “Festivals can come and go, but to sustain something for so many years, you have to work out how to make it valuable for its participants and its audience, by giving people something to work towards.”

The city of Derby, in the UK’s post-industrial Midlands, is not large, but over the last 15 years the biennial event has helped place it on the cultural map. Over the course of each festival some 100,000 visitors will gather there – the city’s compact size lending it some advantages. “Derby is small, like Arles [whose 50-year-old Rencontres photography festival remains the blueprint], so there is this critical mass-like feeling,” says Clements. “People are likely to bump into each other, see our bags and totes – the guides see and integrate them, for example, when we work with the local microbreweries.”

Having visited and collaborated with a number of blockbuster festivals throughout her career, Clements notes that their uniqueness of place, and their social context, are crucial to understanding longevity and success. “Where it doesn’t work is when locations are too spread out, and there are too many exclusive events that separate the audience. Quad [the arts centre that is the epicentre of the festival’s programme] has been working to help understand how an audience ebbs and flows, and how those dynamics work. We host people and make them feel welcome, especially our international guests, who we hope will become part of our network, and who don’t know their way around. It’s a meeting place.”

She adds: “I need to know what it feels like as a general visitor, as a participating artist and special guest, to make sure that everyone has the best possible encounter with our programmes.”

By shunning exclusivity and working hand-in-hand with the local community and local industries, the atmosphere of the festival creates a universal dialogue. Youth clubs and schools even pre-empt the festival theme by working it into their curriculum. “We want the festival to be interesting to everyone,” insists Clements. “Photography is a very democratic medium; even the most complex conceptual iterations of it can be articulated to diverse audiences.”

Everything outlined in the main programme is free to attend, including a series of talks and panel discussions. For the professionals, the opening week is a concentration of carefully-curated activities, including a Brexit Breakfast with American collector William Hunt and photographers Brian Griffin and Lottie Davies (Format opens two weeks before the UK is due to exit the EU), international portfolio reviews, exhibition openings, performances, and the Photo Book Market, curated once again by Polycopies founder Sebastian Arthur Hau.

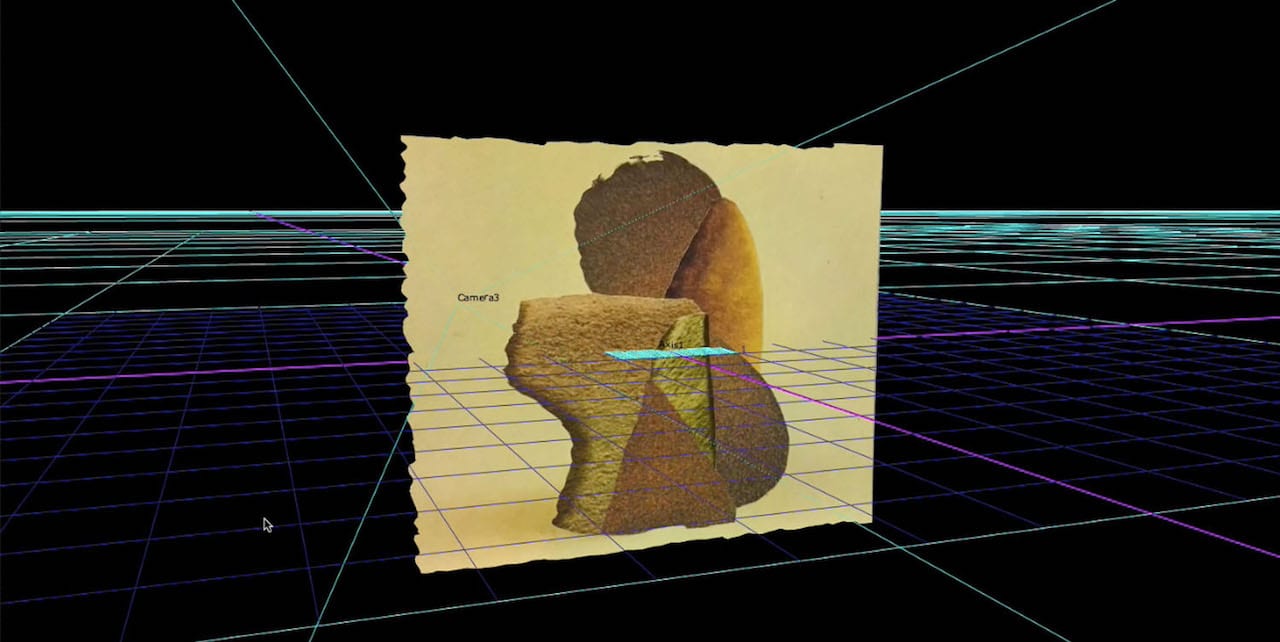

The festival’s theme always investigates some aspect of contemporary life, while at the same time reflecting current trends and approaches in photography – the exhibitions hopefully serving as both a mirror of the times, and a critique. This year’s theme, Forever/Now, is broad, but to unpack it we can begin with the familiar conversation around the gradual yet definitive move towards the imperative use of archiving photography digitally, alongside the many advancements in artificial intelligence and personal communications that now shape our view on the world. It is something that has been widely discussed, and many photographers are embracing new strategies to interpret these cultural and scientific shifts.

But, of course, Forever/Now is not merely a debate about the shift from analogue to digital, it is rather a discussion about the wider implications of the transition and how images are now disseminated and consumed. This year’s edition, as explained in the accompanying catalogue, considers the changing role the medium plays in recording a moment to preserve a “visual memory of the past”. Today, with our smartphones and the almost unlimited availability of storage space in the cloud, we are obsessed with recording every compulsion. Yet, “the immortality photography proffers can quickly sour when digital anonymity becomes virtually impossible to obtain,” the essay reads. “The eruption of selfies and Instagram is contradicted by campaigns around the right to be forgotten.”

As ‘Forever’ looks at the trace we leave behind, the ‘Now’ concentrates on the message. While, in the past, the photograph was seen as truth, even evidence, imagery today no longer deserves such orthodoxy by default. The phenomenon of fake news has put a name to a new sphere where the lines between fact, fabrication and myth are blurred. Definitions of ‘post-truth’ and ‘crooked’ documentary, as defined by Lucy Soutter in the 2007 critical essay, Crooked Photography: Pictorialism and Surrealism, are now commonly understood terms. “The challenge of the photographer is how to establish their message in the now and stop it being transitory,” says the catalogue. Soutter’s writings underpin the theme; her unpacking of the move towards a ‘crooked’, expressive form of photographic enquiry, in which the classic documentary narrative no longer complies to the rules of representation, instead leaning towards interpretation and suggestion.

The month-long event, which runs from 15 March to 14 April, takes over some 30 of the city’s unique venues, from the Museum and Art Gallery and its university, to pop-up venues enlisted into the festival. The lead exhibition, Mutable/Multiple, which most faithfully represents the overarching theme, is at Quad, the city-centre arts complex that initiated and runs the festival. Put together by Clements and independent curator Tim Clark, the group show brings together six projects that “fundamentally challenge documentary conventions,” says Clark. Max Pinckers will show his latest project, Margins of Excess, alongside Stefanie Moshammer’s I Can Be Her, Amani Willett’s The Disappearance of Joseph Plummer, Anne Golaz’s Corbeau, Virginie Rebetez’s Out of the Blue, and Edgar Martins’ What Photography Has in Common with an Empty Vase.

Uniting these photographers together in one space, “they represent some kind of collective self determinism,” says Clark. “As a way of engaging and creating the multiple and mutable realities of our world, they all see the documentary genre as a hybrid one. The projects bring together different approaches and different forms, so that their images shift – they’re quite promiscuous – from the informative to the theatrical, incorporating fine art, documentary and socially constructed narratives.”

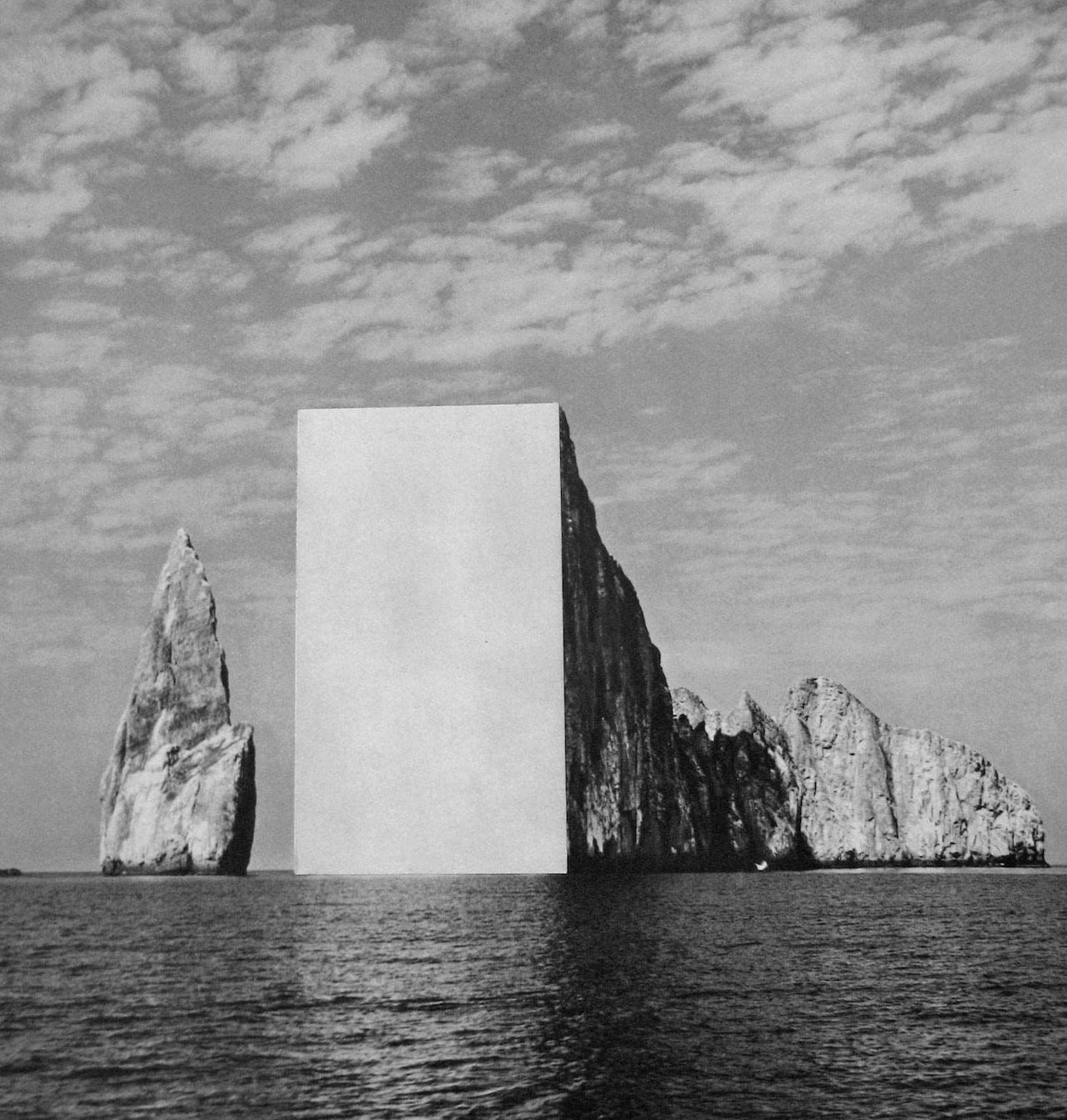

Using archival material, newspaper clippings, text and staged photography alongside more conventional documentary approaches to visual storytelling, the photographers elicit themes of disappearance, fractured backgrounds, longing, isolation and fantasy. They photograph the invisible: “the ontological level of the photographic medium – how one represents a subject that often eludes visualisation, which is absent or hidden from view – that’s a key thing,” says Clark.

For example, visualising the absence of an individual, such as the mysterious disappearance of Suzanne Gloria Lyall in 1998, which is the focus of Rebetez’s work. On the other hand, what if disappearing is the intention? This is the subject explored by Willett, who imagines tracing the movements of a hermit – Joseph Plummer – who lived 200 years ago. “They’re all working, to a certain extent, with a documentary impulse,” says Clark.

“A lot of them build in self-awareness that critiques that method, and when storytelling they offer narrative portals to the imagination. They recognise the documentary character of photographs, but only as a conventional idea, I’d say, or as a point of departure. They all posit an argument that insists on the ambiguity of the photographic evidence, and they embrace the greater challenge of variable truths.”

Quad’s Gallery Two will host a special commission by Kensuke Koike, who featured in our BJP‘s Cool + Noteworthy issue. Known for his intricate collages, the Japanese artist will present a wallpaper-esque sculptural installation, drawing on the archives of what’s claimed to be the world’s longest-surviving photography studio, WW Winter, which is still based in Derby. Using some of the earlier prints as his source material, he takes the opportunity to meditate on the disused archive and recalibrate it under a new light. The University of Derby hosts the debut of Jack Latham’s Parliament of Owls – a quasi-investigative work looking into the secret activities of an exclusive gentlemen’s retreat, located in the middle of a redwood forest in California. This too leans towards the “ambiguous” documentary style explored by the photographers showing in Quad.

In another notable thematic group, Sixteen presents the work of 14 photographers, including Abbie Trayler Smith, Simon Roberts, Kalpesh Lathigra and Jillian Edelstein. The brainchild of Craig Easton, the project was thought up during the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum, when 16-year-olds were permitted to vote for the first time in the country’s history. Thus the multimedia project, a collection of vox pops, video and photography, collates the faces and opinions of teenagers from all around the UK, exploring their thoughts and feelings on their future, entering into adulthood and living in a world constructed for them by the older generation.

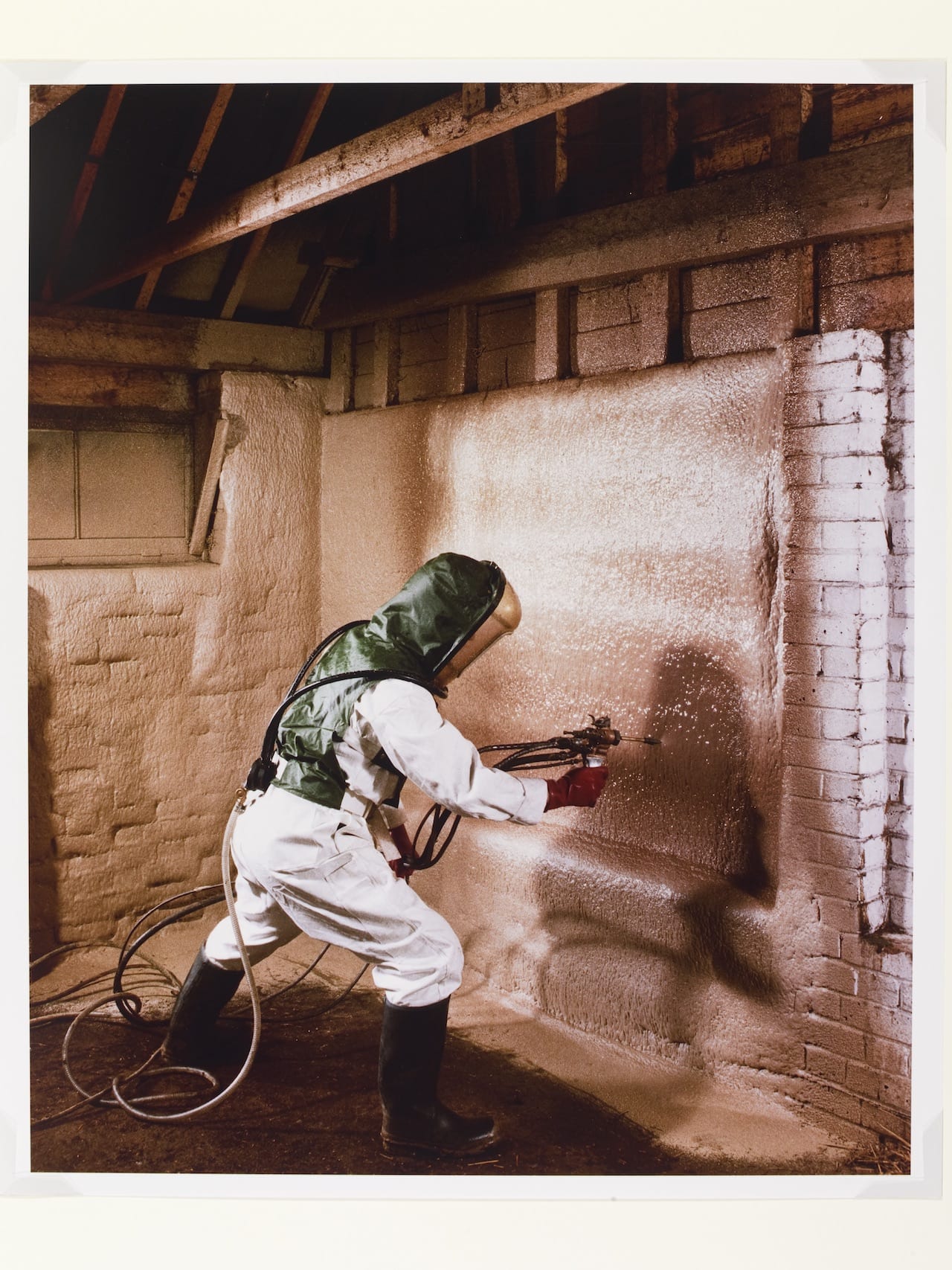

While the festival is one of contemporary photography, an exhibition of the work of Maurice Broomfield is a nod to the area’s historic importance in the story of the Industrial Revolution – the nearby Derwent Valley Mills are the birthplace of the factory system. Curated by Martin Barnes, the V&A’s senior curator of photographs, White Heat of British Industry, 1950s-60s collects images by Broomfield from both the archive housed in the London museum, and the Derby Museum and Art Gallery, where they will be displayed.

The larger prints, newspaper clippings, as well as never-before-seen contact prints highlight a period of immense change, as modern industrial advances accelerated. Here are portraits of the men and women working hands- on in the factories, shipyards, paper mills and car-makers, celebrating a community of workers that barely longer exists.

Every edition, the open call extends the invitation to new talent, receiving an impressive 657 entries by photographers from 47 countries all over the globe this year, judged by a panel of photographers and experts, featuring Brian Griffin, Peggy Sue Amison, BJP’s editorial director Simon Bainbridge, Sheyi Bankale, Wang Baoguo, Sam Barzilay, Alexa Becker, Louise Clements, Huw Davies, Christine Eyene, Yumi Goto, Frank Kallero, Erik Kessels, Kim Knoppers, Dewi Lewis and Caroline Warhurst, Lola MacDougall, Fiona Rogers and Lars Willumeit. The 54 successful projects, which will be shown in Quad’s extra gallery spaces, include works by Emily Graham, Ronghui Chen, Maria Sturm, Liza Ambrossio, Michele Palazzi, Nina Röder, Eleonora Agostini, Elena Anosova and Alexandra Lethbridge, among others.

The open call is an important part of appreciating emerging talent, and the same goes for the portfolio reviews – an integral part in the development of photographers, and nurturing the community around them. These interactions, as well as chance encounters facilitated by gathering in the walkable city of Derby, have led to fruitful collaborations and partnerships between artists. Clements explains that those who impress are always remembered – their development and progress followed over many years.

“I watch someone grow and it might take me 10 or 20 years to then decide to work with them. It’s about exposing and showing work that’s not shared too widely, but also celebrating projects that people want to see first hand,” she says. “There are many projects that I am proud to have led, featured and to have been part of, too many to mention, but generally speaking the benefit of having a sustained programme since 2004 has meant that we have seen people grow with the festival. Some young people who participated in the early days have gone on to have careers in the arts.”

Clements’ hopes for the festival are that it is inclusive of everyone, while also supporting and paying attention to each participating photographer individually. “We work towards every single artist as much as possible; there is no blanket approach to exhibiting,” she says. The same goes for the accompanying activities of the programme: “Hosting and perfecting the content of, and access to, the listings is very important – this is the frontline of the festival, which enables the programme to be a success and for all of the contributors and audiences to feel engaged. Alongside this, vision and courage when programming can enable a little to go a long way; something presented in a poor context can be an incredible highlight when presented well.

“It has always been my intention for the festival to work beyond the programme that we present, for it to be a catalyst in the cultural ecosystem that enables and encourages activity beyond our control. This was just an idea in the early days, but now it is a reality.”

Format takes places in multiple venues across Derby, UK from 14 March to 15 April formatfestival.com

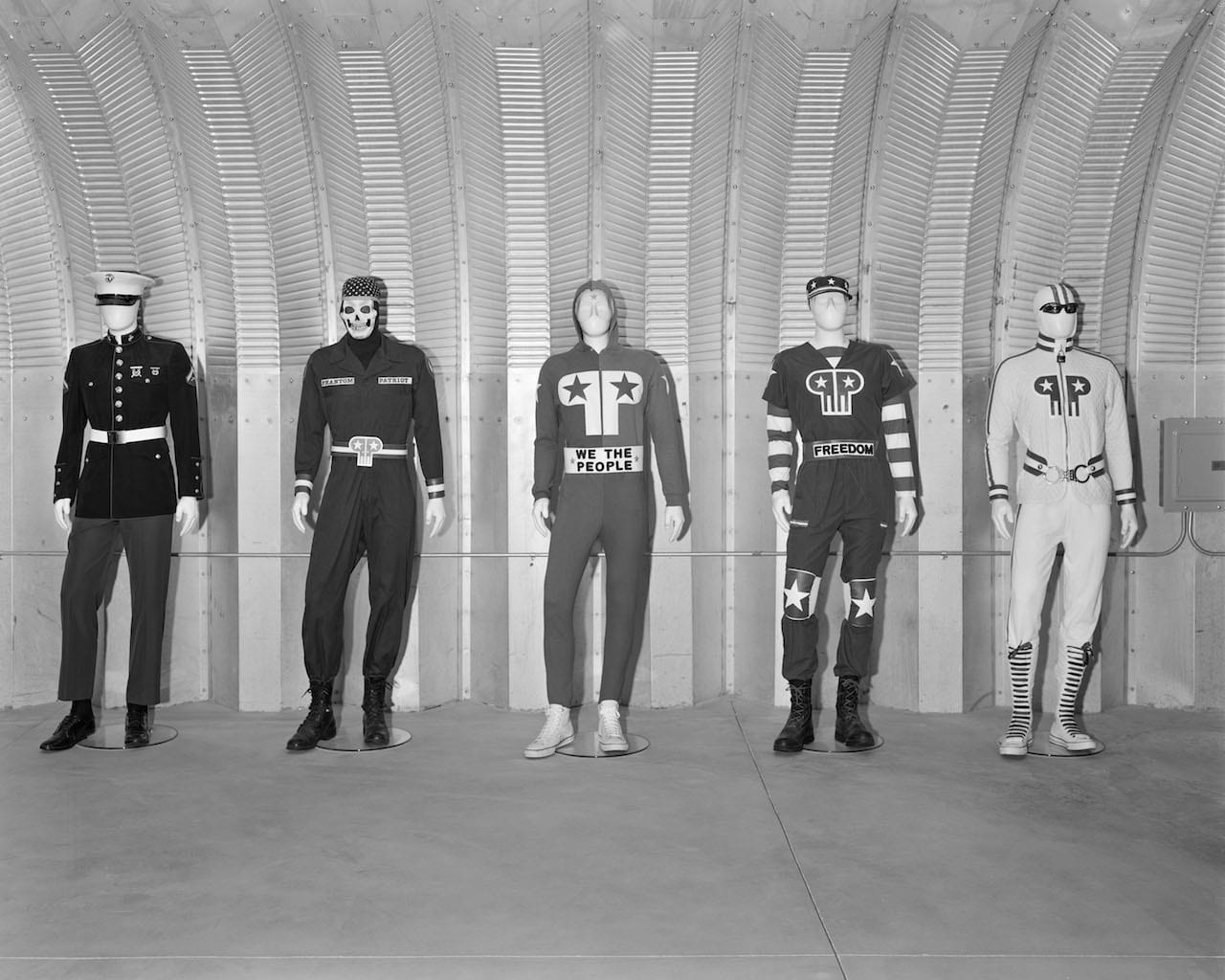

I went into these places with the intention of understanding something apart from myself, and in the process, created a picture of America that mirrors my own confusion of navigating a cultural identity that time is moving past © Garrett Grove

lmost 300 years ago, people came to colonize Siberia, then assimilated into the Evenkis (little nation) and founded a village in the taiga [the snow forest]. Katangsky District, Irkutsky region. Russia, 2016. From the series Out of the Way © Martin Godoy