“Given my own life story, maybe I have a bit more of an understanding of what it means to be forced out, to be on the edge of society,” says Thilde Jensen, who lived in a tent in the woods for 18 months back in 2004. “I was homeless too for a while, but for different reasons.”

At the age of 30, Jensen had developed severe Environmental Illness, also known as Multiple Chemical Sensitivity. The symptoms are wide-ranging, and can include headache, fatigue, nausea, and respiratory problems, caused by a severe sensitivity to chemical exposure – be it perfumes, detergent, or even synthetic fabrics and plastic.

Jensen wore a respirator for seven years, and was unable use her phone or laptop because she also became sensitive to electronics. For the first year and a half Jensen lived in her tent, or in the desert under the open sky. Eventually, she found an alternative treatment from Canada that targeted the illness through the brain, and in 2013 published her first book, The Canaries, about people who suffer from Environmental Illness.

“It was very disabling” says the Danish photographer over the phone from upstate New York, where she now lives in a straw-built house in the countryside. Jensen has recovered, but has to take precautions in her lifestyle, particularly when travelling. Ironically, perhaps, these factors also made it easier to photograph homeless people than many others for her next project, because they live outside and don’t use fragrances or detergents she could be sensitive to.

Titled The Unwanted, her forthcoming book is also all too relevant now, with numbers of people without homes thought to be soaring around the world. Accurate statistics are hard to collate, but in the UK, the number of people who declared themselves homeless hit a record high in 2018, and reported rates of homelessness in other countries in Europe are also rising. Jensen’s photographs were taken in the United States, but speak to the parallel experiences of over 100 million individuals worldwide, as estimated by the UN.

It all began in 2014, when Jensen met two homeless men – Reine and Lost – in Syracuse, New York. They had survived three bitterly cold winters under a small concrete ledge built beneath a highway, where icy winds would whistle relentlessly through the underpass, as if in battle with the roaring traffic overhead. “It blew me away,” says Jensen. “I got drawn into thinking about what it felt like to live outdoors, having done it myself.”

The Unwanted was shot over four years, in four American cities – Syracuse, Gallup, Las Vegas, and New Orleans – and completed with the support of a Guggenheim fellowship. Jensen is currently raising funds on Kickstarter to publish a book of the work, which will include 120 colour images, as well as a poem by Gregory George – a homeless man she met in New Orleans – and an essay by respected photography critic Gerry Badger.

Jensen was keen to shoot in Las Vegas, because she saw the city as a paradigm of capitalist America, and knew there was large homeless population there. But funding was tight, so over four one-month stints, lived out of her car without shower or laundry facilities. After a while, Jensen felt that people were beginning to look at her differently. “I was starting to be treated like someone who was not desired, who was unwanted,” she says. “I got yelled at by a guard in a parking lot”.

Jensen explains how our daily routines like showering, getting dressed, or choosing what to have for breakfast all subtly contribute to a sense of our identity. “When that disappears it gets harder and harder to keep together who you really are,” she notes.

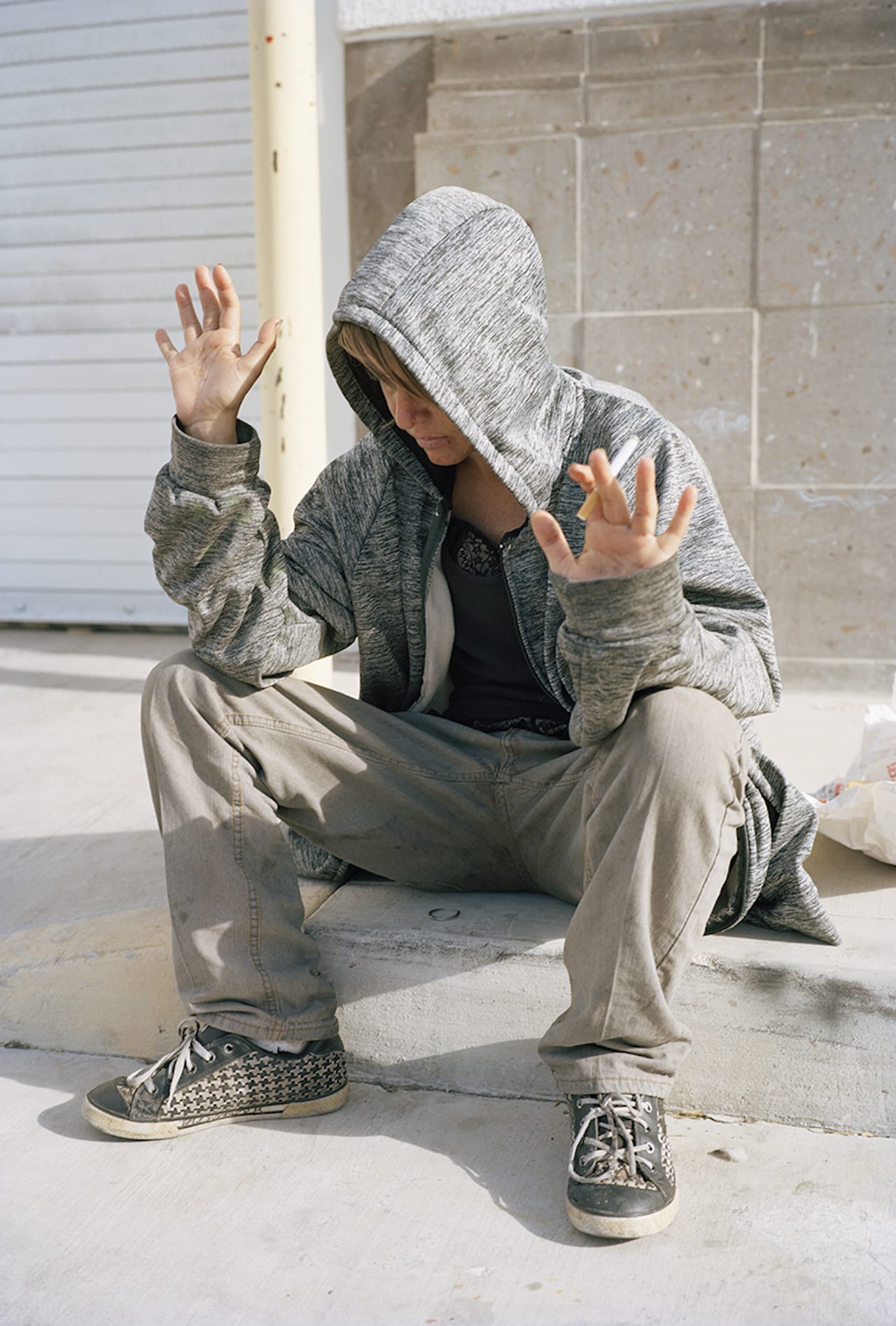

Over the four years she spent photographing and building relationships, Jensen became close with her subjects, and says she misses them now. “I think there is an honest, raw, human nakedness to people on the street,” she says. “When everything is stripped away, when you don’t have material goods, when your titles are gone, you’re just left with you. There was a realness to the interactions I had.”

But shooting vulnerable people can also invite criticism. It raises questions of whether the images are exploitative, or if the photographer truly has the license or full consent. “I think there is a fine balance, but it’s important to look,” says Jensen. “If we don’t look at them, or if we try to sanitise it, then it’s not honest to this brutal experience of being homeless.

“I didn’t want to romanticise it, or show it in a way that I felt wasn’t truthful,” she continues, using Diane Arbus as an example of a photographer who was criticised for taking images that some regard as voyeuristic from a point of privilege. “I’ve always felt that to her, they were not freaks, no more than she herself was a freak. It goes back to how we take photographs of other people. There is some part of it that is a self portrait. I can’t photograph someone who I can’t feel.”

During The Canaries project, when Jensen was running back and forth between the camera and her bathtub – naked with a respirator attached to her head – she thought back to Arbus’ photographs of the nudist camp. “The behind the scenes of those photographs would be equally interesting, because Arbus herself was walking around naked with a camera around her neck,” she laughs.

“There has to be a side of me that can understand the people I photograph. I think the licence comes from that – from being human, being open enough to have an extreme level of intimacy that allows you to feel other people and hold them in a photographic embrace. I don’t ever feel like I’m above anything that I photograph.”

Still, Jensen recognises that when she was homeless, as such, it was in a different context to the people she photographed – her life’s outcome could have been entirely different if she hadn’t had the means to support herself through her illness. “It all comes down to poverty,” she says. “Mental health and substance abuse aren’t reasons alone to become homeless.”

And though these problems were common among people she met, she adds that it was difficult to know whether their mental health issues had contributed to their homelessness, or a side effect of living on the street, “an escape to deal with the pain”.

Everyone had a different story, but one of the more common narratives Jensen encountered involved prison. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and some of those who are discharged get sent straight to a homeless shelter. On top of not having a permanent home, or a valid form of identification, a criminal record makes it even harder to get a job.

“I think a lot of people end up on the street because of neglect – whether it’s from society or from friends and family,” says Jensen. As someone who has experience of living in solitude, Jensen knows the importance of human contact and attention, and on the street, she found that it could be transformative. At first, some of her subjects were visibly agitated by her presence, but by the end they were “like different people,” she says, greeting her with hugs.

“Human connection is key for all of us. If we can create a society that treats the most vulnerable in our society better, we all benefit from that,” says Jensen. “I hope that the photographs help shed light on this experience, and these people who are out there, and I hope it does it in an honest way that gives the viewer some of the experience. I hope it lets you, even for a short period of time, feel that this could be your life.”

https://thildejensen.com Thilde Jensen is currently raising funds to publish The Unwanted https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/thildejensen/the-unwanted-1