During the Wellcome Photography Prize submission period, which closes 17 December 2018, British Journal of Photography is profiling photographers who are exploring the importance of health in society and the impact health issues have on people and communities worldwide. In line with the Outbreaks category, BJP spoke to Anastasia Taylor-Lind about her project The Surge, a series on the campaign to eradicate polio in Afghanistan.

In 2013, Anastasia Taylor-Lind spent three days in Jalalabad, a city in eastern Afghanistan, photographing the campaign for polio eradication. The majority of her images were taken over a weekend during which she followed vaccinators providing polio immunisations to children under five. The outcome is a collection of quietly observant photographs that depict what she sees as “the far-reaching effect of conflict on infrastructure, community and healthcare.”

It was back in 1988 that the World Health Assembly resolved to eradicate polio. Since smallpox was eliminated in the late ‘70s, no other human disease has been extinguished. Polio, however, has come close. Today, only Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan are classified as “not polio free” by the World Health Organisation. Outbreaks of the paralysing virus are endemic to remote crisis zones: places such as Jalalabad where there is a cultural, political or geographical barrier to vaccination.

Investigating the relationship between war, disease and gender is what drives Taylor-Lind’s work. Photojournalism has historically eschewed the far-reaching effects of war, relying instead on graphic depictions of violence. Taylor-Lind’s approach, by contrast, highlights the after-effects of conflict and the less immediate impacts on communities. “This is a health story as well as a war story. When we think about people being killed in conflict and conflict-zones we think about people being blown up and shot, and of course, those things do happen, but actually the consequences and suffering of people who have war visited on them are long-term,” she explains. For the past decade, the photographer has travelled the world on commission for magazines, revealing the traumatic yet rarely covered consequences of war.

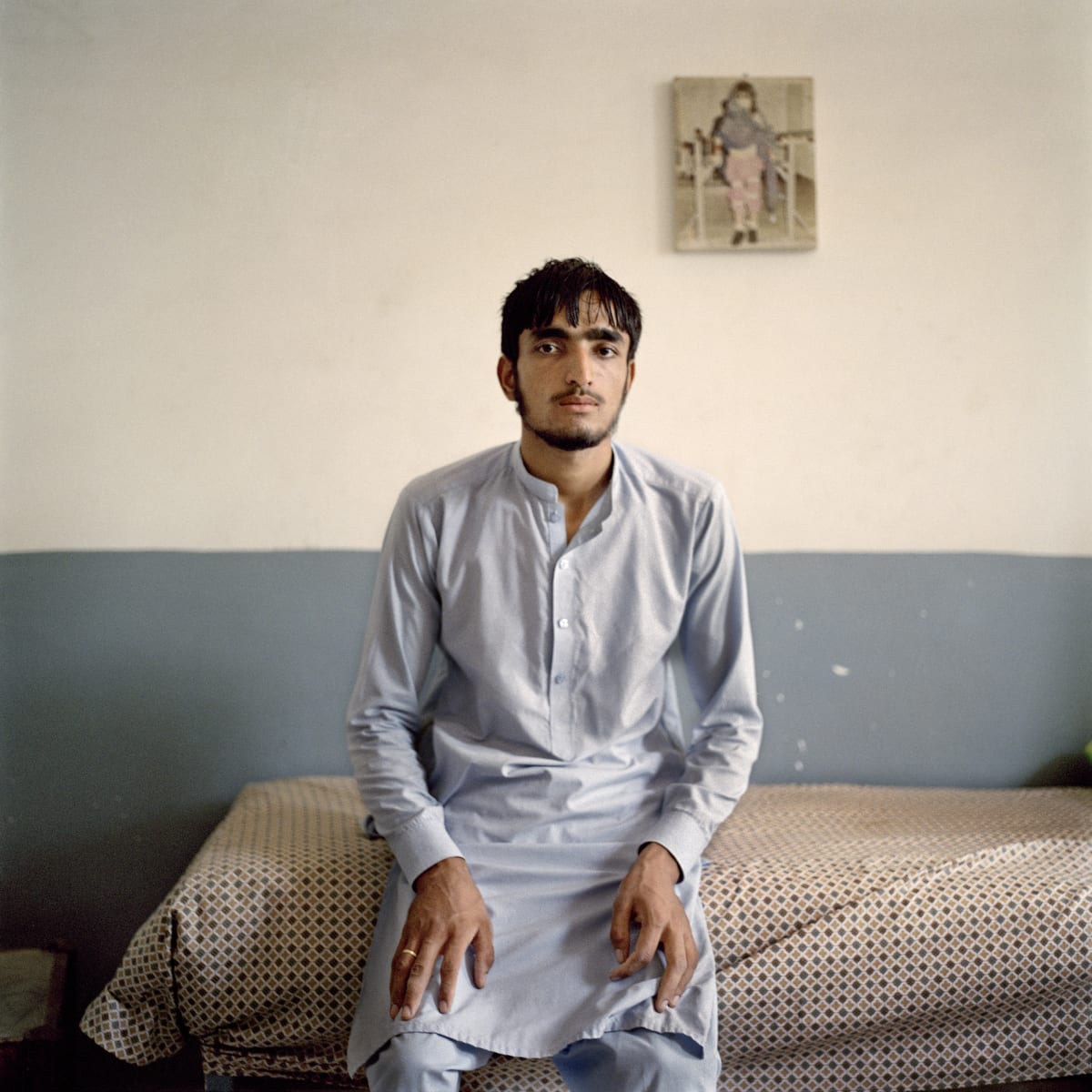

Being a female journalist worked in Taylor-Lind’s favour for this project, which involved gaining access behind closed doors. In Afghanistan, it is more acceptable for women to enter strangers homes than men. Though Taylor-Lind was travelling with a writer, driver and translator she was the only female and therefore the only one able to follow the vaccinators inside homes to meet families. “The imperative here is that they must vaccinate everyone,” she explains. Once a child had been vaccinated they would have their fingers dipped in purple ink and their front door was marked to signify the house had been immunised. Taylor-Lind went from door-to-door with different healthcare teams, entering into domestic, private spaces of people’s homes. “You don’t need to cover if you are alone with women. I was wearing a shalwar kameez but I would take off my headscarf and women would remove their burqas when there were no men present,” she says.

The fact that 22 polio vaccinators had been murdered in the months before Taylor-Lind’s arrival serves as a brutal reminder of the dangers that women face when working in the field. In order to protect themselves from the very real risk of being assassinated, most women wore their burqas for her photographs. “Two women agreed to show their faces with just a hijab but that was a negotiation and rightly so,” says Taylor-Lind.

It is this discord, this “vast chasm between a lived experience in a place and a photo that somehow tries to represent that experience,” as Taylor-Lind describes it, that makes the photographer question the limitations of photojournalism. “Do we need to see more pictures of women covered in burqas without their faces showing? What does it teach us about Afghanistan when you see pictures of women like this?” she asks. “I think that having a faceless woman may be damaging in terms of representation.”

The determination and resilience of those depicted in The Surge is palpable. Whether it is felt in the unrelenting stares of healthcare teams or the attentive faces of children receiving aid, these people remain steadfast in the face of this debilitating disease. “These are not passive women. Actually, they are pretty heroic,” says Taylor-Lind. Although her trip to Afghanistan was short, she delved into how she could go about challenging the stereotypical representation of this group. “Even though they are wearing burqas, I hope that I managed to represent these women with some dignity and agency,” she says. “I am just hoping that by holding that blind spot in my peripheral vision I can make a difference with my work.” The Surge serves as a reminder of the power of photography to provoke thought and its ability to raise awareness around outbreaks in all corners of the world.

The Wellcome Photography Prize is calling for work that will shed light on, and raise awareness about, stories of health, medicine and science. Each category winner will receive £1,250 and be featured in a London exhibition; the overall winner will receive £15,000. Entry is free and the deadline for submissions is 17 December 2018.

–

This article is supported by Wellcome Photography Prize. Please click here for more information on sponsored content funding at British Journal of Photography.