Çağdaş Erdoğan is known as a photographer who doesn’t take much time off. But, on 02 September last year, he decided to take a walk through his adopted home of Istanbul. He meandered across the city to the popular Kadıköy district and, with his cameraphone to hand, took a stroll through Yogurtçu Park, a picturesque tree-lined public space close to the Fenerbahçe football stadium.

Erdoğan described photographing a “parliament blue” sky against the park’s pastel greens, the cityscape of Istanbul lying in the distance, at his subsequent pretrial hearing in the city’s Çağlayan Courthouse. Erdoğan, who is 26, said to the judge: “I was taking pictures of the Yogurtçu Park because of the harmony of the colours I noticed in the moment. I didn’t see any buildings, only a fence.

“Then a man who identified himself as a policeman asked me what I was doing. I explained that I was walking around and just taking pictures. My concern was that of a photographer interested in taking a good photograph. He asked me to delete the pictures from my cellphone. I deleted the only one that I had taken.”

In Erdoğan’s frame, the police claimed, was the Millî İstihbarat Teşkilatı (MİT) building – in which the shadowy figures of Turkey’s answer to MI5, the National Intelligence Organisation, work. The policeman informed Erdoğan that in Turkey it is illegal to photograph the building in any way. As he was questioned, a car of plain-clothes police officers arrived. Erdoğan was cuffed, arrested, and loaded into the car. That sunny, solitary afternoon in Yogurtçu Park was his last taste of freedom. Erdoğan has remained in Istanbul’s Silivri prison on a pretrial detention charge, ever since.

On 13 February, he will stand trial in Istanbul accused of membership and support of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a separatist group classified as a terrorist organisation by the Turkish government. Erdoğan is of Kurdish descent, grew up in the region and, as an adult, embedded with affiliates of the PKK during the complex, multifactional conflict that has crossed the borders of Syria, Iraq and Turkey. But he did so, he claims, purely as a photojournalist intent on documenting an unseen conflict for the world’s media and without any alliance with or allegiance to any organisation. His only allegiance was to photography.

Represented by 140journos SO, a newly-formed independent photography agency based in Istanbul, Erdoğan’s images of the conflict have been published by The New York Times, Associated Press, BBC, and The Guardian, among others. During his interrogation, Erdoğan was accused of “insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Turkish flag, and state institutions”, as well as “spreading propaganda in favour of the PKK terrorist organisation,” according to a message from his lawyer, sent to friends via an intermediary. Photographs on his website and disseminated on his Facebook page were cited as evidence.

“Photographing a building is not even a crime, much less an act of terrorism,” says Robert Mahoney, deputy executive director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, a New York-based NGO that campaigns on press freedom. “Çağdaş Erdoğan is being punished for being a journalist whose work the authorities don’t want published. These preposterous charges should be dropped, and he should be freed immediately along with the scores of other journalists in Turkish jails.”

In a message sent from prison to his friends, which was passed to British Journal of Photography, Erdoğan described his arrest: “On the second day of Eid [02 September] in Yoğurtçu Park, I was taken into custody because I was taking pictures of an ‘invisible’ building which belongs to the state. I learnt the actual reason of why I was taken in custody when they took me to the police station. The pictures I have been taking for international newspapers and magazines constitute a crime.

“The pictures, which have been published primarily in The New York Times, The Guardian, and BBC, are treated in scope of ‘conducting activities in the name of a terrorist organisation’. Moreover, the counsel of prosecution presented my photos of dog fights that take place in my book Control, which has been published in London, as evidence of PKK membership.”

Turkey is currently the biggest jailer of journalists in the world, with around 73 of them currently held in the country’s prisons, according to figures from the Stockholm Center for Freedom from the start of 2018. The majority of these cases, the Center states, are at the pretrial stage of conviction. Outstanding detention warrants remain for 139 journalists. More than 900 press cards have been revoked, and more than 2,500 other journalists have lost their jobs since summer 2016. Turkey is currently listed as 155 out of 180 countries in terms of its freedom of press.

George Georgiou, a renowned British documentary photographer represented by Panos Pictures, was outspoken in his defence of Erdoğan when the news broke of his arrest, and has since been involved in co-ordinating the campaign to secure his release. Georgiou and his partner Vanessa Winship lived together for a while in Istanbul, and they retain strong relationships in the city and with its photo community. On a visit in 2015, Erdoğan sought out a meeting with Georgiou.

“He told me that he had a strong respect for the work I do. And he told me he wanted to delve deeper into his stories,” Georgiou says of their meeting. The pair developed a mentorship.

“He’s at the forefront of a new generation of Turkish photographers who have a real desire to speak truthfully in their photography,” Georgiou says. “He’s young, fearless, he has a lot of drive, and he’s earnest. [His work] doesn’t gloss over the subject. It looks at the issues. He has this very strong sense of truth and justice. He wanted to learn how to translate that feeling into his images.”

At around the same time, Erdoğan involved himself with a community of photojournalists in the city who, for various reasons, had fallen foul of the authorities. Together, they launched 140journos SO, an independent photography agency that aims to provide the Western media with objective and truthful accounts of the civil unrest and resurgent authoritarianism of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey.

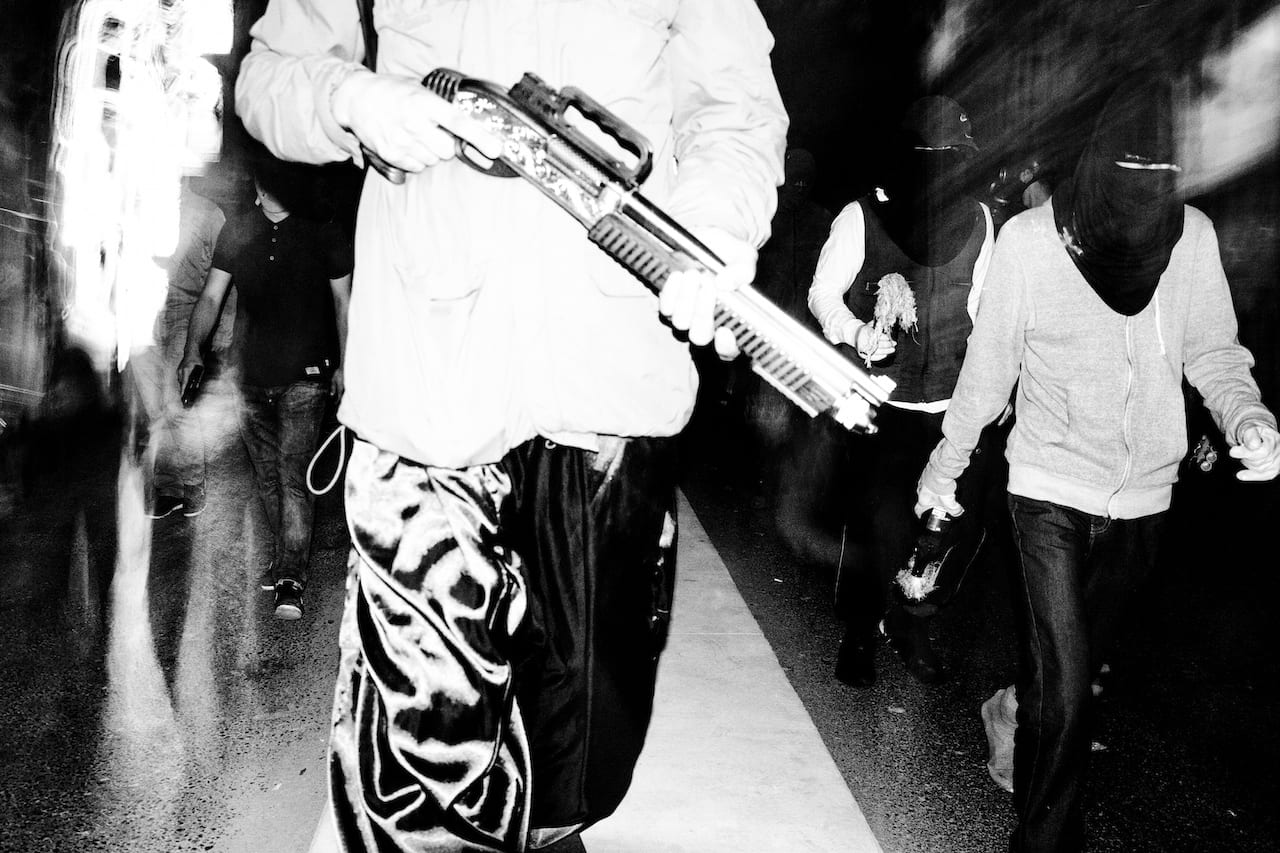

Erdoğan based himself in Gazi, an impoverished suburb of the city known for its entrenched Kurdish community, as well as its proclivity for criminal behaviour. He started to embed himself in the many countercultural communities that existed in the district. In doing so, Erdoğan quickly gained a reputation in the agency as an especially fearless and capable photojournalist. A friend talks of watching a protester throw a Molotov cocktail at an armoured water cannon during a riot in Gazi. Erdoğan ran just a metre behind with his camera, looking through the viewfinder.

His deep engagement with Gazi also helped him to develop and publish of Control, a remarkable study of what happens when certain groups are repressed by the state. The book was published by Akina Books after the owners, Alex Bocchetto and Valentina Abenavoli, met Erdoğan in a photobook workshop. They started to push him to take a more conceptual, ambient approach to his subject matter, to develop a practice rooted in photojournalistic disciplines, yet informed by contemporary sensibilities.

The publication tessellated images of illegal dog fights, what Erdoğan calls “sex parties”, and the often violent political – or at least countercultural – protests which take place among the hidden communities of Gazi. “The story of a night in Istanbul includes sex workers, dog fights, gun violence and political armed conflict,” Erdoğan wrote of Control on its release. “At first glance, these activities seem different. But once we delve deeper into these stories, we can see they are part of the same chain of motives.”

Before he was arrested, Erdoğan told Georgiou and his friends that he was aware he was being monitored. “He knew he was at risk of being arrested,” Georgiou says. “His eyes were open to that. But I think, for the sake of his reporting, he was willing to take that risk. He was willing to find those stories. That desire was there, to report what was going on in his country.”

His colleagues at 140journos SO, who prefer to remain anonymous, say that accusations of terrorism against Erdoğan could not be further from the truth. “Erdoğan abhors violence. He is totally against violence and loathes guns,” a representative says. “As a child, he has seen destruction first-hand.”

The 140journos SO collective reached out to the major publications that had published Erdoğan’s work in the wake of his imprisonment. “After his arrest, he really was expecting the photography publications he worked for to come forward,” says his friend. “He asked us to reach out to them, and we did. He thought they would give him their support, but none of them did.”

https://cagdaserdogan6.visura.co/ akinabooks.com 140journos.com

www.1854.photography/2017/09/cagdas-erdogan-arrested-in-istanbul/

www.1854.photography/2017/09/cagdas-erdogan-writes-from-his-istanbul-prison/

www.1854.photography/2017/06/cagdaserdogan/