Luce Lebart has hopped across the Atlantic Ocean to take the helm of the newly-minted Canadian Photography Institute (CPI) after five years as the collection director and curator of the Société Française de Photographie – an association founded in 1854 to celebrate and promote the then-emerging medium, and the oldest of its kind in France. The CPI fills the large gap left by the abrupt and permanent closure of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography in 2009, thanks to the support of Scotiabank, the Archive of Modern Conflict and the National Gallery of Canada Foundation. The photographic image now has a permanent home some 600 square metres large in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and the CPI has a mandate to strengthen visual culture locally, and to nurture and advocate for Canadian image production.

Luce Lebart: When I first looked into the Institute and what it promised to be, I was impressed. As someone who wants to make room for the wide array of photographic practices, approaches and genres, it struck me as a paradise since it purports to do just that. Case in point: the diversity of its collection. The National Gallery of Canada started collecting photography fifty years ago and has acquired prints by most seminal artists – Henry Fox Talbot, Eadweard Muybridge, Josef Sudek, Diane Arbus, Lisette Model, Walker Evans, and so on. Just before my new appointment, I put together an anthology of the great photographers of the 20th century for Larousse, and of the 56 images I picked, nearly all are in the holdings of the CPI.

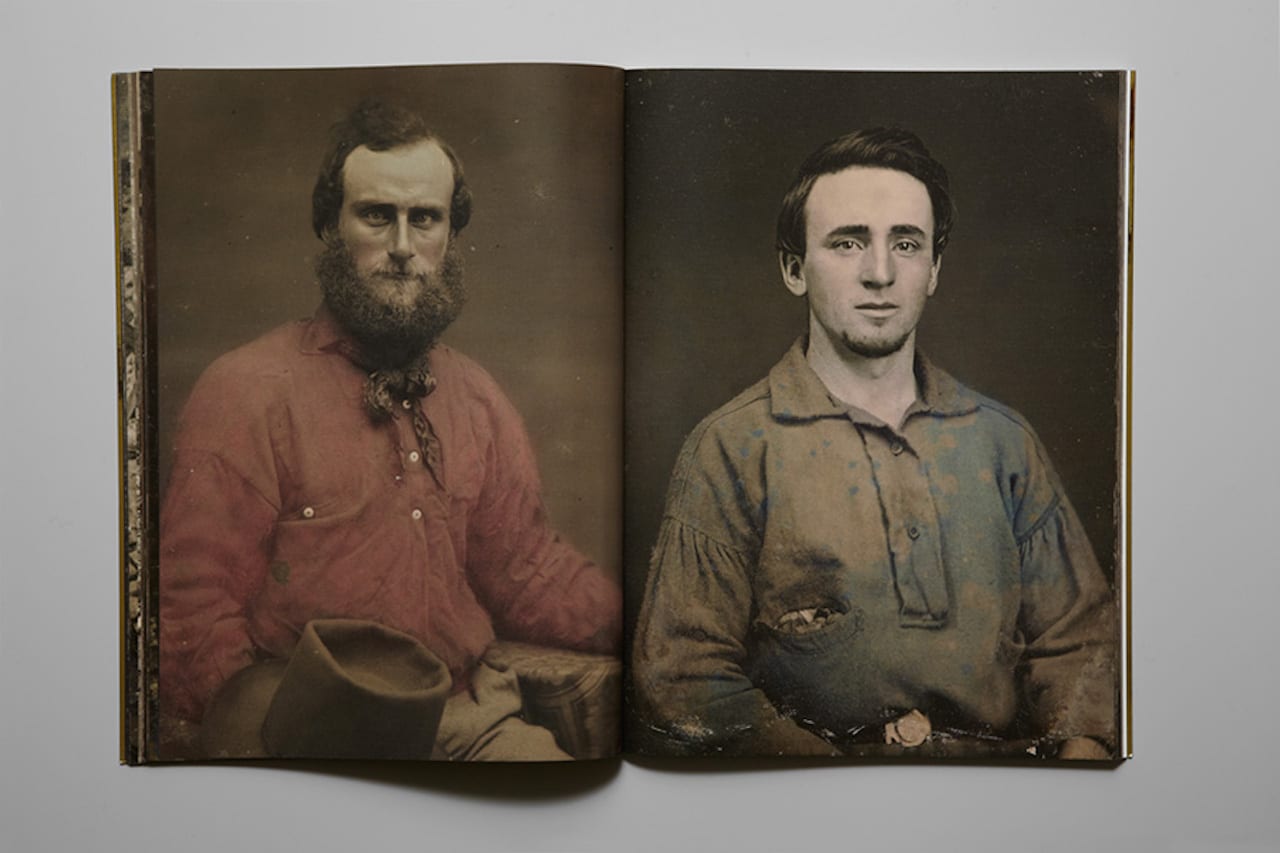

And that’s not all. We’re also the stewards of the nearly 160,000 works formerly held by the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, which includes a large selection of images from the National Film Board’s still archives, a gold mine for examining how the country’s identity was constructed, as well as works by contemporary Canadian artists. Moreover, since its creation in 2015, the CPI has received several donations – most notably from Archive of Modern Conflict, which bequeathed over 11,000 daguerreotypes, books and related objects from the Origins of Photography collection. Many of those pieces are by anonymous authors, which can be dismissed by cultural institutions that celebrate the Author.

In short, the CPI is unique in that it marries a museum-like collection with archival and vernacular holdings. That’s what excited me.

LL: Our challenges are more or less the same as those faced by any cultural institution, including finding the space to care for the works we’re entrusted with properly and devising the means to ensure their vitality. By that I mean, that the pieces ought to be seen by the public and by academics, so that they can stimulate thought and scholarship. We have to keep in mind that photography is malleable, that with time the uses and meanings of an image can shift.

With that in mind, we’ve created research fellowships and invited candidates from a range of background to apply. Our first cohort include an art historian interested in the National Film Board’s use of photography to build a national identity, a doctoral student in chemistry focusing on preserving daguerreotypes, and a researcher exploring French “primitive” photographs, amongst others.

LL: This duality guides our annual exhibition programming. While we have major shows that look at different aspects of Canadian photography, others focus on contemporary issues that also affect Canadians. For instance, the summer show was Photography in Canada 1960-2000; in the spring, we’ll be looking at 50 years of the photography collection at the National Gallery of Canada. In between, we’re focusing on broader themes that still resonate nationally, such as immigration, borders, territorial expansion, etc.

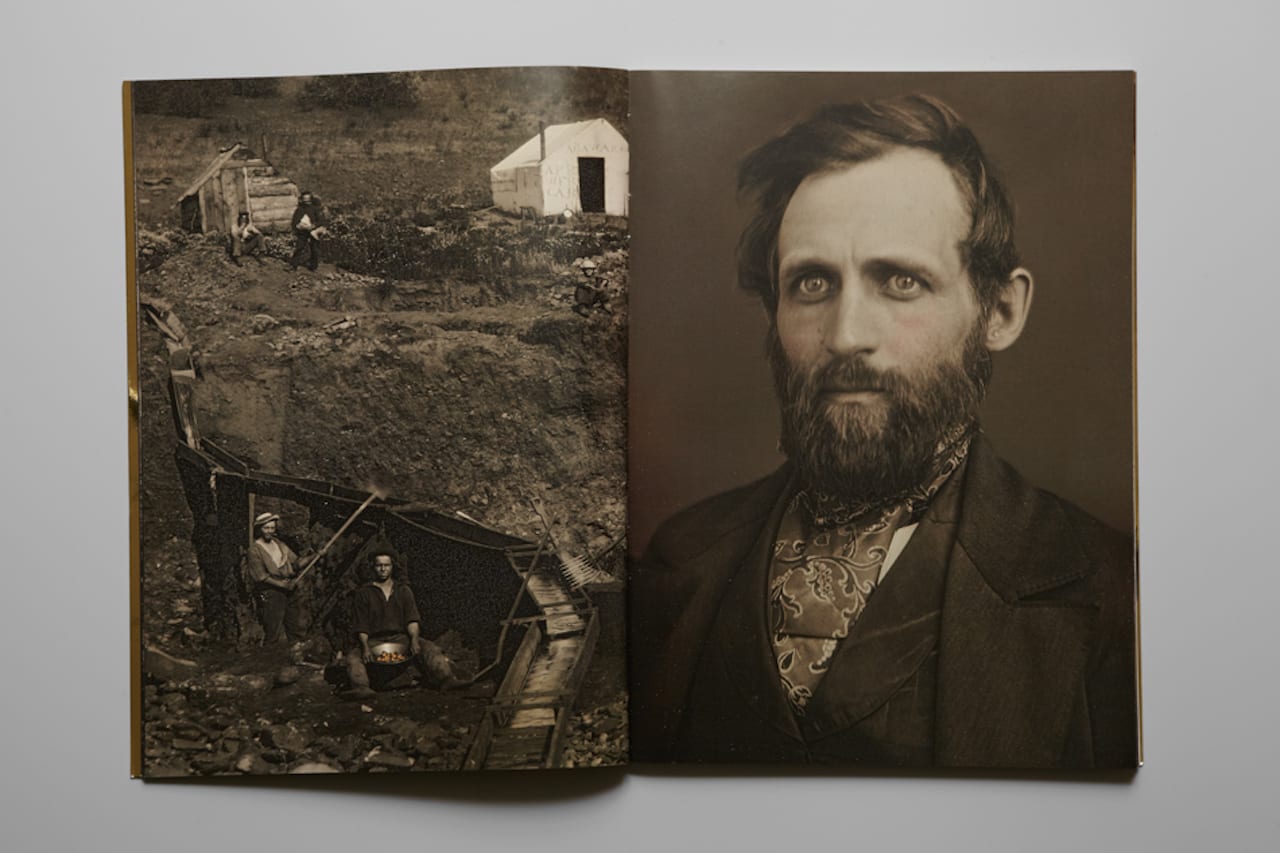

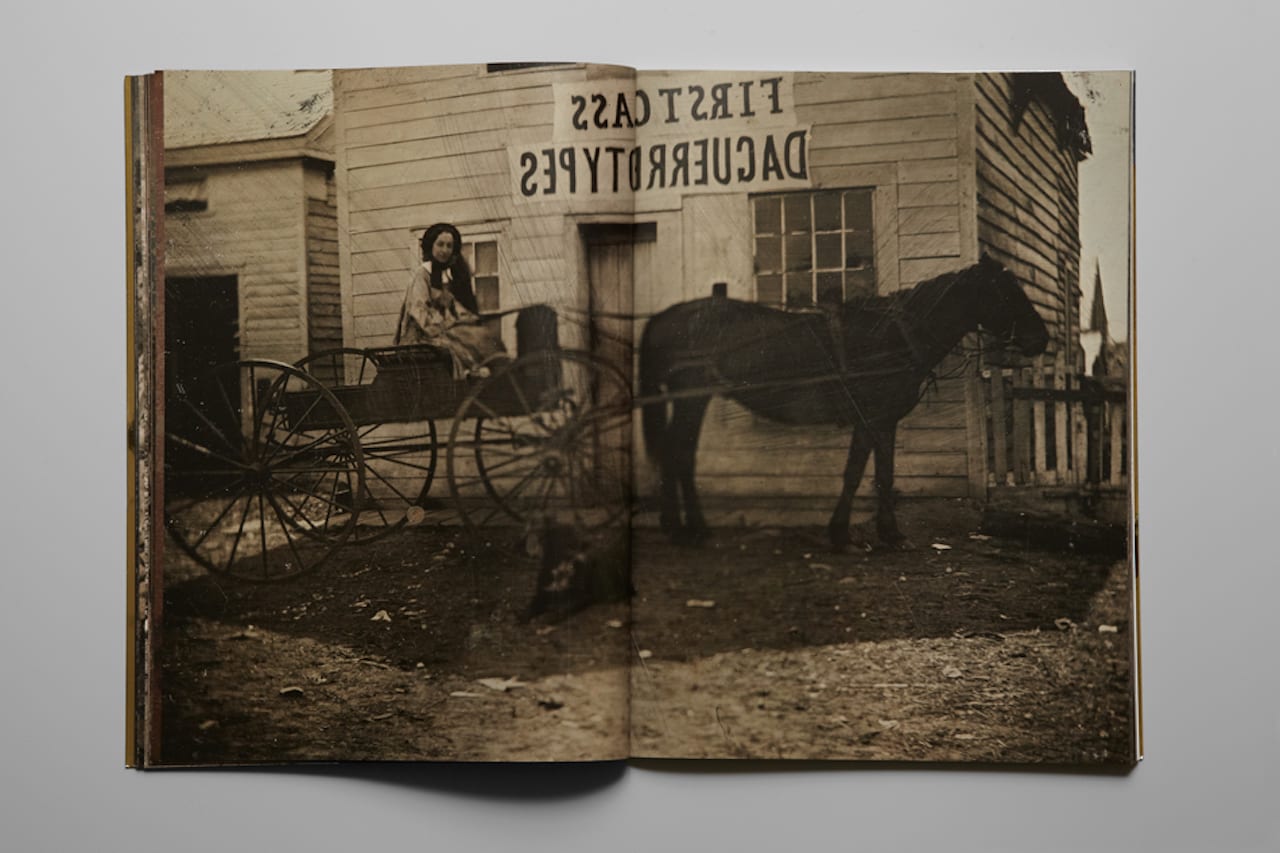

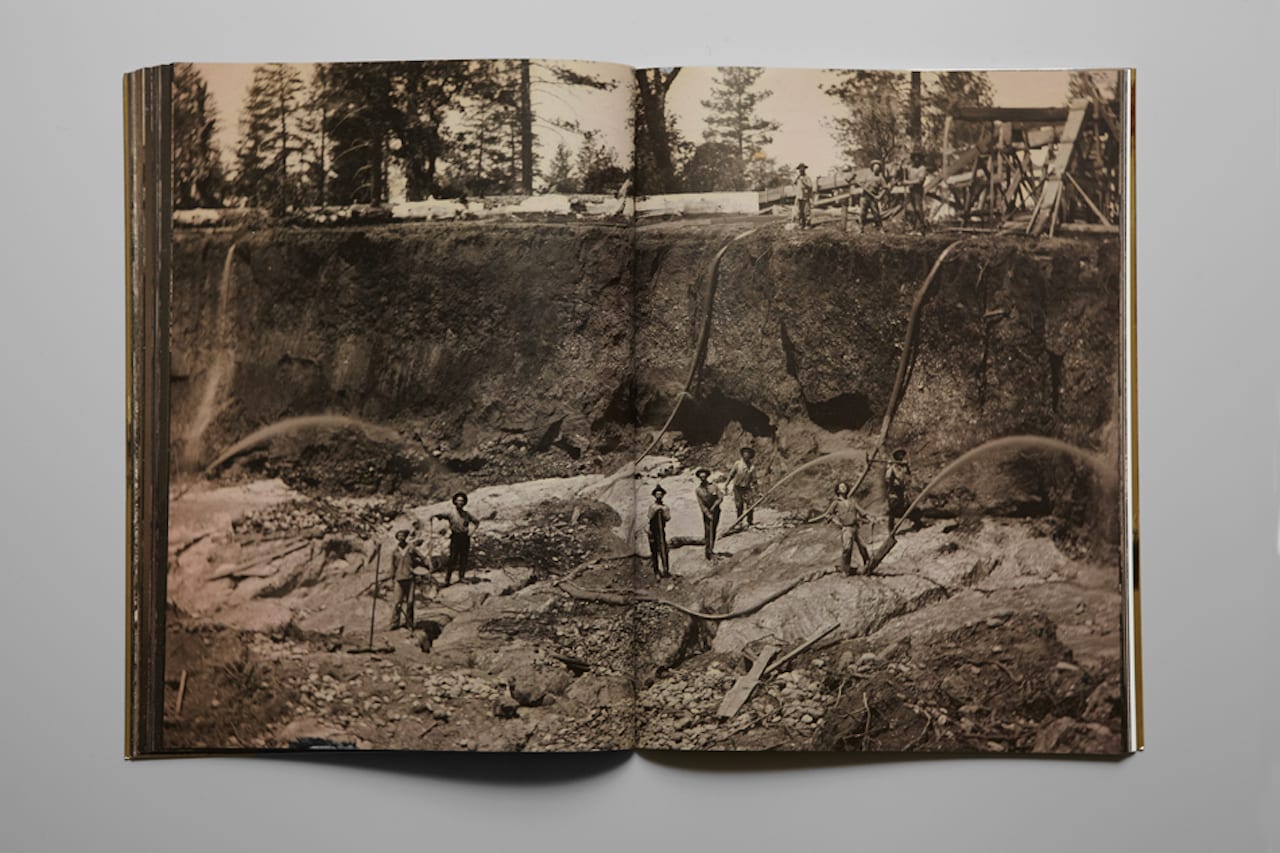

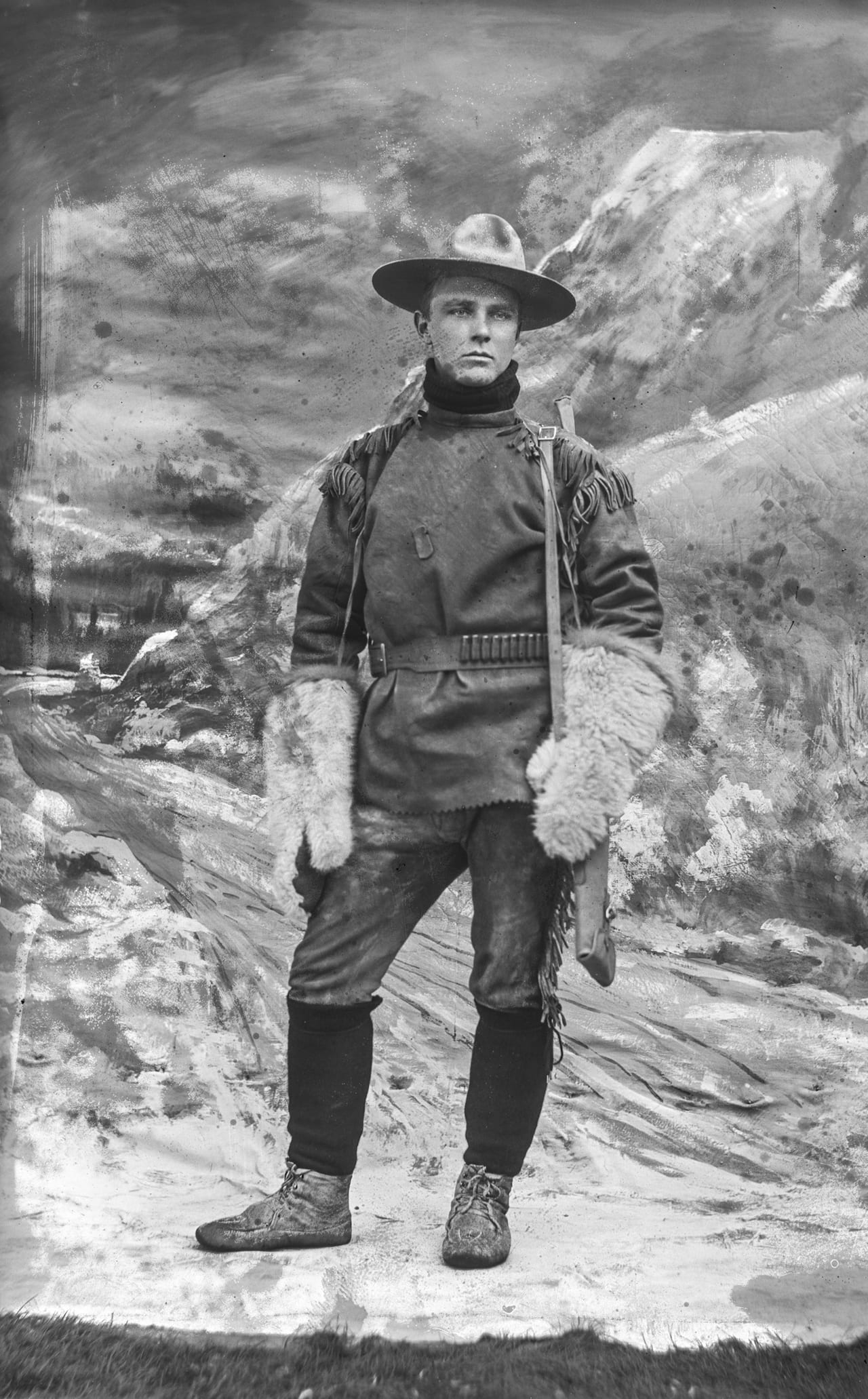

The autumn/winter exhibitions include Gold and Silver: Images and Illusion of the Gold Rush, a defining moment in the history of North America as well as photography. I once read a letter written by Samuel Morse after he visited Louis Daguerre in March 1839, in which he described the work of his French colleagues as perfected Rembrandts. When I look at the daguerreotypes of the Gold Rush, I see what he meant. The tonalities are incredible and the detail is inconceivable.

Simultaneously, we’re showing Frontera, which centres on the border between Mexico and the United States. It includes works by artists from here, Geoffrey James and Mark Ruwedel, whose practice often revolves around question of cultural landscape, as well as some made by their international counterparts – Pablo Lopez Luz (Mexico), Alejandro Cartagena (Mexico), Adrien Missika (Swiss), Kirsten Luce (USA), German Daniel Schwarz (USA). In line with that exhibition our experimental space, PhotoLab, is dedicated to young Canadian photographer Andreas Rutkauskas, who photographed the Canada-US border, inspired by the 1975 National Film Board book Between Friend/Entre Amis.

BJP: The history of photography in Canada is quite young, much like the country itself. That must be quite a departure from what you’re used to in France?

LL: Indeed, they are vastly different universes. Yet although Canada’s relationship with photography is comparatively young, it is deeply entrenched. Preparing our current exhibition on the Gold Rush, I learned that Canada, a country younger than photography itself, named cities after photographers. In the show, we’re displaying a photo album by the geologist George M. Dawson, who was mandated in 1887 to map the Yukon area. He travelled by canoe and produced sublime images akin to the road trip genre, except that instead of the road extending into the distance, you have waterways, and instead of the dashboard of a car in the foreground, you have the tip of a canoe. His name was given to Dawson City, which was the capital of the Yukon territory until the early fifties. The country is full of surprises, just like the collections of the CPI!

Gold and Silver: Images and Illusions of the Gold Rush is on show until 02 April, 2018; an accompanying book by Luce Lebart has been co-published by RVB Books and the Canadian Photography Institute, priced €38 https://rvb-books.com/book.php?id_book=176

PhotoLab 3: Between Friends, on show until 16 February 2018; Frontera: Views of the U.S.-Mexico Border, on show until 18 March, 2018. https://www.gallery.ca/cpi