“When I talked to people whose relatives had been killed, I could understand how difficult it was to forget, to go forward,” says Mariusz Smiejek. “The numbers were so huge; many families in Northern Ireland experienced it.”

More than 3600 people were killed and some 50,000 were maimed in The Troubles, in atrocities committed by both sides. The 30-year sectarian conflict officially ended in 1998 with the Good Friday Agreement but, as the Polish photographer has discovered, for some it’s proving hard to move on.

For him, the most visible sign of this struggle comes every year on 11 July, when Ulster Protestants burn huge bonfires in celebration of the 1690 Battle of the Boyne. First lit when the battle was still raging to guide British ships to shore, the bonfires subsequently became an act of commemoration. Smiejek saw them the first time he went to Belfast and, curious about the people involved, took “a few years to get close to them”.

Working with local NGOs, he discovered that many of them are relatively young, but had parents who fought in The Troubles. “It’s passed on from generation to generation,” he says.

Sectarian by nature, the bonfires always stir up trouble – and particularly so when they’re used to burn Irish flags, or other national or religious symbols, something which NGOs and people on the ground are working hard to change. “If you ask the bonfire builders why they do it, some of them reply, ‘Because they are Catholics, and for us it’s a symbol of the IRA, that’s why we burnt it [the flag]’,” says Smiejek.

“But I noticed very they had little knowledge about the history…They don’t necessarily understand what happened during The Troubles, they are basing their convictions on the stories they were told by their parents. That’s why there is still a lot of work for NGOs, youth workers and community workers, to educate the younger generation and work with them on the ground.”

www.mariuszsmiejek.com

The youngest builders on Belfast’s Upper Shankill are five or six years old; for them this is a playground and a place to hang out with friends. The most engaged constructors spend several hours a day at work; sometimes they begin mustering up materials as early as January – wooden pallets, furniture, anything which can be set on fire. Some of the bonfire structures contain many tyres, which annually triggers stormy discussions in the local media about environmental protection. Year after year community workers and NGOs work with local residents to remove tyres from bonfires. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

The youngest builders on Belfast’s Upper Shankill are five or six years old; for them this is a playground and a place to hang out with friends. The most engaged constructors spend several hours a day at work; sometimes they begin mustering up materials as early as January – wooden pallets, furniture, anything which can be set on fire. Some of the bonfire structures contain many tyres, which annually triggers stormy discussions in the local media about environmental protection. Year after year community workers and NGOs work with local residents to remove tyres from bonfires. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

14-year-old Cory is one of hundreds of youngsters in Northern Ireland who build bonfires year after year; this is his third in a row. Most of the material comes from local residents and businesses who sponsor its purchase and transport; in this case the wood has been delivered by former members of a British paramilitary organisation in Northern Belfast. Dozens of bonfires are organised in Belfast itself, out of the hundreds built in Loyalist neighbourhoods across Northern Ireland. Each such district can apply to the local City Council for financial subsidies to cover the costs of organising these events. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

14-year-old Cory is one of hundreds of youngsters in Northern Ireland who build bonfires year after year; this is his third in a row. Most of the material comes from local residents and businesses who sponsor its purchase and transport; in this case the wood has been delivered by former members of a British paramilitary organisation in Northern Belfast. Dozens of bonfires are organised in Belfast itself, out of the hundreds built in Loyalist neighbourhoods across Northern Ireland. Each such district can apply to the local City Council for financial subsidies to cover the costs of organising these events. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

Johnny (first from the left) is a youth worker and volunteer for a local organisation which brings together and supports ex-combatants in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Johnny spent two years in prison for participation in riots; upon release he decided to work with the youth of his neighbourhood. Here he meets with youngsters by a bonfire structure on Belfast’s Shankill Road, where he heads a club for bonfire-building children and adolescents. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

Johnny (first from the left) is a youth worker and volunteer for a local organisation which brings together and supports ex-combatants in post-conflict Northern Ireland. Johnny spent two years in prison for participation in riots; upon release he decided to work with the youth of his neighbourhood. Here he meets with youngsters by a bonfire structure on Belfast’s Shankill Road, where he heads a club for bonfire-building children and adolescents. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek

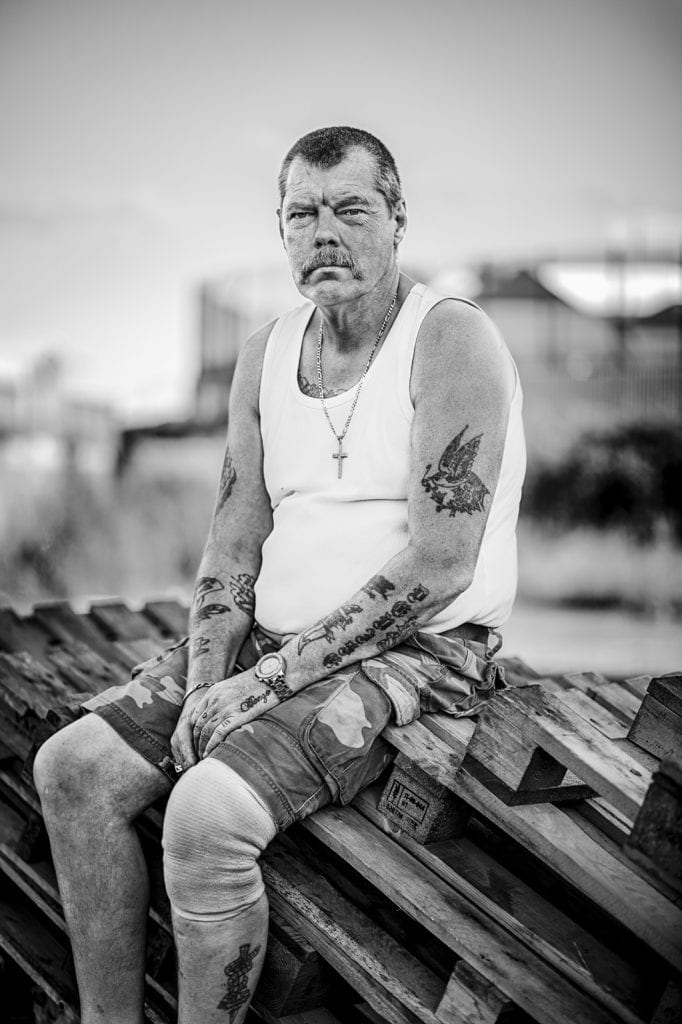

Michael, a wood collector and van driver from the Greater Shankill area, photographed after delivering another set of wooden pallets to the Conway Street bonfire. Most of the bonfire builders are between 10-30 years old, but more adults are involved with delivery, and some of them are ex-combatants. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek, courtesy of the artist

Michael, a wood collector and van driver from the Greater Shankill area, photographed after delivering another set of wooden pallets to the Conway Street bonfire. Most of the bonfire builders are between 10-30 years old, but more adults are involved with delivery, and some of them are ex-combatants. From the series Bonfires – Belfast, Northern Ireland (2015-2016) © Mariusz Smiejek, courtesy of the artist