A 13-day coma, four brain haemorrhages, a fractured cheekbone, a broken collarbone, a broken humerus, two collapsed lungs, several broken ribs, a cracked pelvis, a dislocated knee a shattered foot, an amputated toe and a splenectomy. After a near-fatal accident leaves you with this catalogue of injuries, you might consider a more gentle hobby than dirt biking.

“Izzy got back on [his bike] at the first opportunity – albeit with a newfound respect for safety. He continues to perform stunts and is one of the most controlled and skilled riders I’ve met. That kind of dedication, to me, demands respect,” says Murphy, whose series celebrates the prowess, passion and style of a secret and often stigmatised subculture.

“People don’t look back on the career of Evil Knievel and think of him as a menace – nor do they of any extreme sports person that risks life and injury in the pursuit of pushing the boundaries,” he adds. “These are pioneering sports people at the start of something.”

Now an award-winning photographer, renowned for his portraits of sportspeople, politicians and actors, he still finds himself drawn to “people or groups that exist on the fringes of society” in his personal work. He’s photographed surfers, eco-commune residents, and gypsy and traveller horse fairs.

He first came across the world of dirt biking in 2013 via the documentary 12 O’Clock Boys, about bikers in Baltimore, but it wasn’t until a couple of years later when he started to see dirt bikes and quads more regularly on the roads, and in the papers, that he decided to try and document the scene.

Following months and months of seeking an ‘in’, Murphy was on the verge of giving up when Izzy, of the Supa Dupa Moto’s crew, got back to him. They met for the first time at a disused air strip in south London but it was Murphy’s second encounter with dirt-biking – this time in north east London – that stuck in his mind.

“You can’t really prepare yourself for the attack on the senses: the noise of that many motorbikes, the smell of petrol, burnt rubber and weed smoke and the post-apocalyptic scene they create,” he remembers.

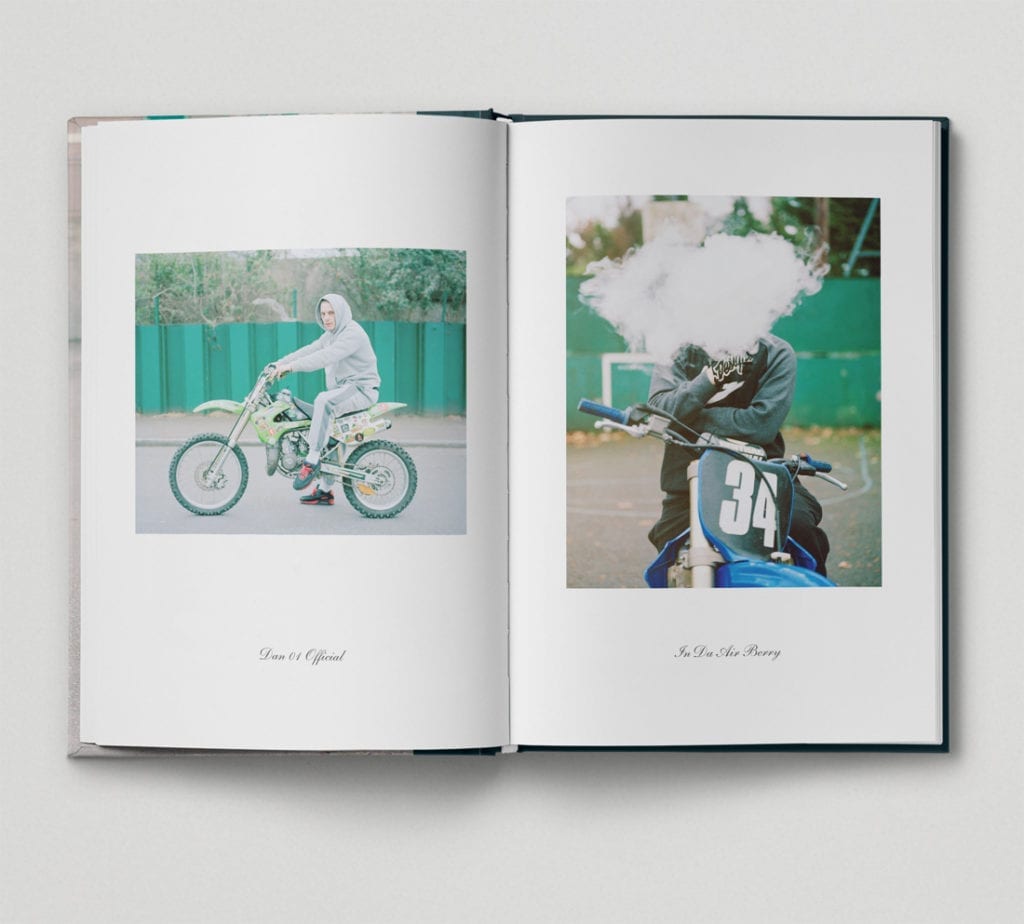

Murphy shot the project on medium format film. “I enjoy not only the aesthetic results but also the process. This was second nature when photographing the more controllable elements but extremely hit and miss when trying to capture the action. The spaces were often only a road width deep and the action was unpredictable, so trying to manually focus a hulking great medium format camera at the speeds they were travelling presented a very new challenge.”

“I look for a poetic hook,” Murphy explains. “The action to me was an important element, but the people, the style, the bikes and the marks they left behind were just as, if not more important in the telling of the story.”

“It’s seen from the outside as antisocial or even criminal, and perhaps the attack on the senses I mentioned is partly to blame for this. Seeing a masked, track-suited youth atop a noisy dirt bike isn’t perhaps the most welcoming sight,” he says. “But for these kids, this is an outlet to escape the drudgery of the inner city, a place to express themselves.”

“What I saw was a diverse group of friends, in pursuit of something that made them feel free.”

Urban Dirt Bikers is published by Hoxton Mini Press, available to purchase from today!