It’s a terrible shock and great sadness to be writing about Ed in the past tense. He was a great friend of mine for nearly 40 years, a man who believed passionately in the power of photography to show how people live, how they protest against the powerful and how people create things that counteract the corporate machine.

We worked together on many projects for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) and at the Half Moon Gallery and its magazine Camerawork. Ed was one of the original members of the collective at the Half Moon in Alie Street, Whitechapel, with fellow photographers Jenny Matthews, Mike Goldwater and Paul Trevor. This was to prove to be incredibly dynamic and brilliant group who curated numerous influential photographic exhibitions, many of which were by photographers who have continued to produce important work, as they have themselves.

Ed had the idea of laminating the exhibitions, at first because the roof leaked in Alie Street and plastic lamination made them waterproof. He began touring the laminated exhibitions, sending them by train in a travelling box to venues all around the country. I produced one called a Document on Chile, about the military coup in Chile, which went to youth clubs, town halls and if my memory serves me right, a launderette.

It was a fantastic way to get the work of young, socially concerned photographers out to a non-specialist audience, and the exhibitions and the Camerawork magazine have influenced how photography is viewed in society ever since. It is currently being archived and placed online by Four Corners Photo and Film.

It was a stunning exhibition, bringing out all Ed’s skills as an exhibition designer, and the photographs looked as strong and deeply sympathetic to their subjects as they did three decades ago. The Women’s Peace Camp at Greenham Common can now be seen to have had an enormous influence on mass popular protest, especially on the Occupy movement, and Ed’s work from this period has played a big part in keeping its memory alive.

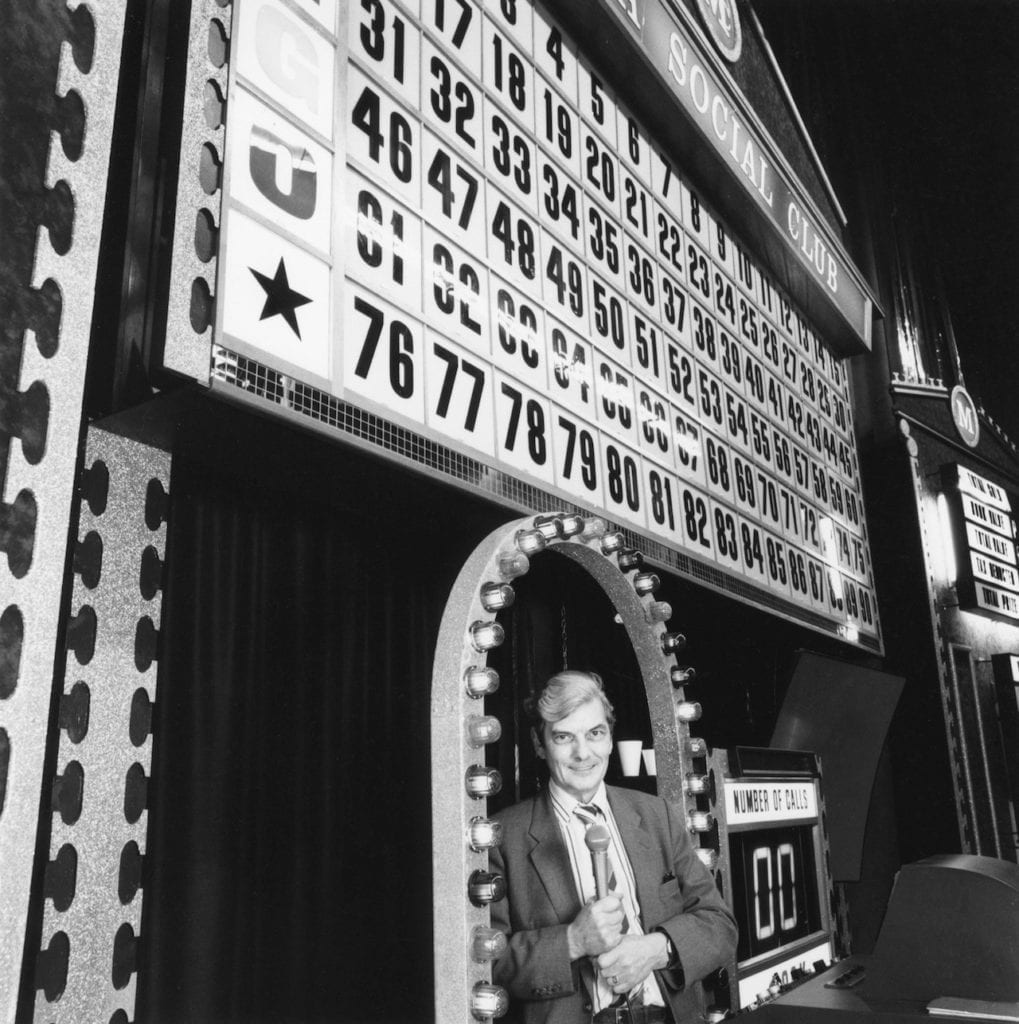

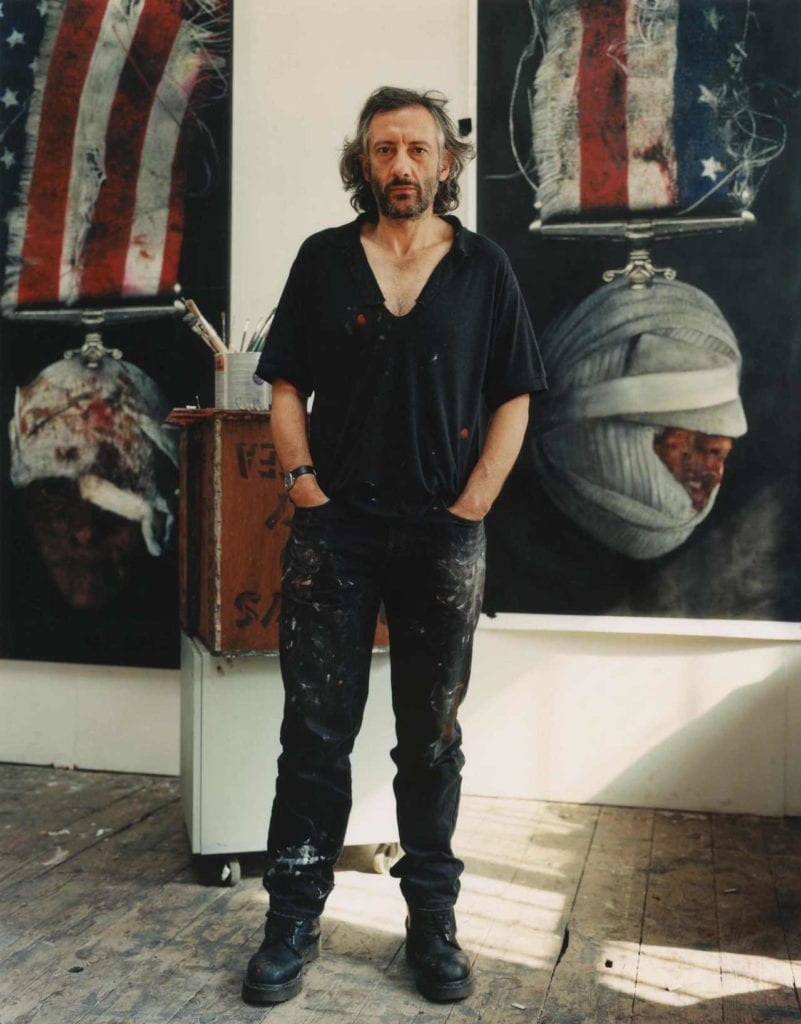

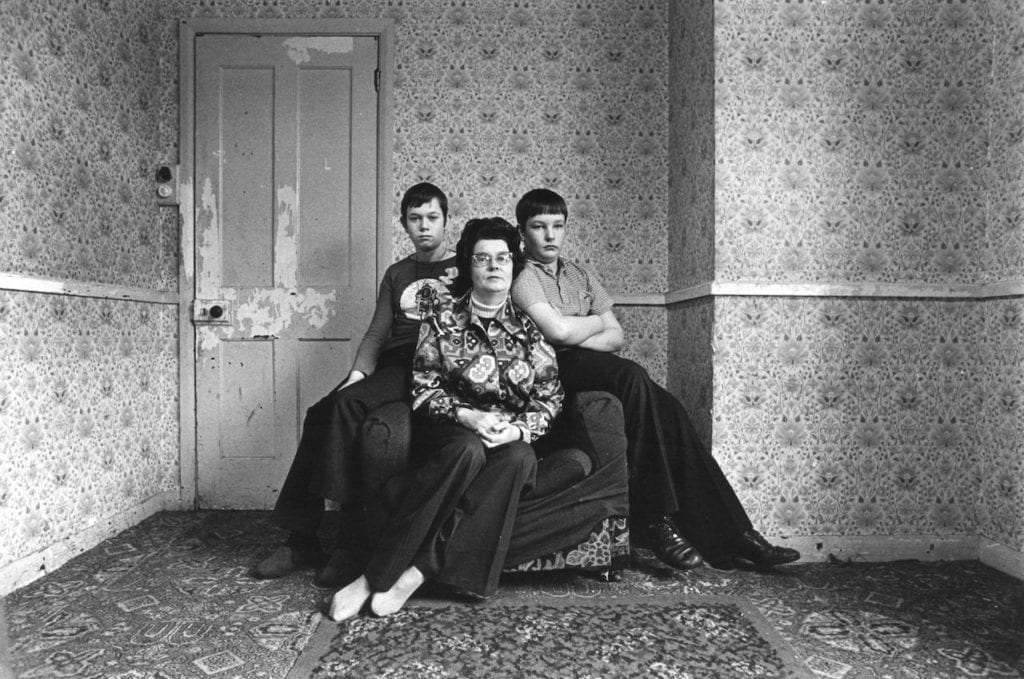

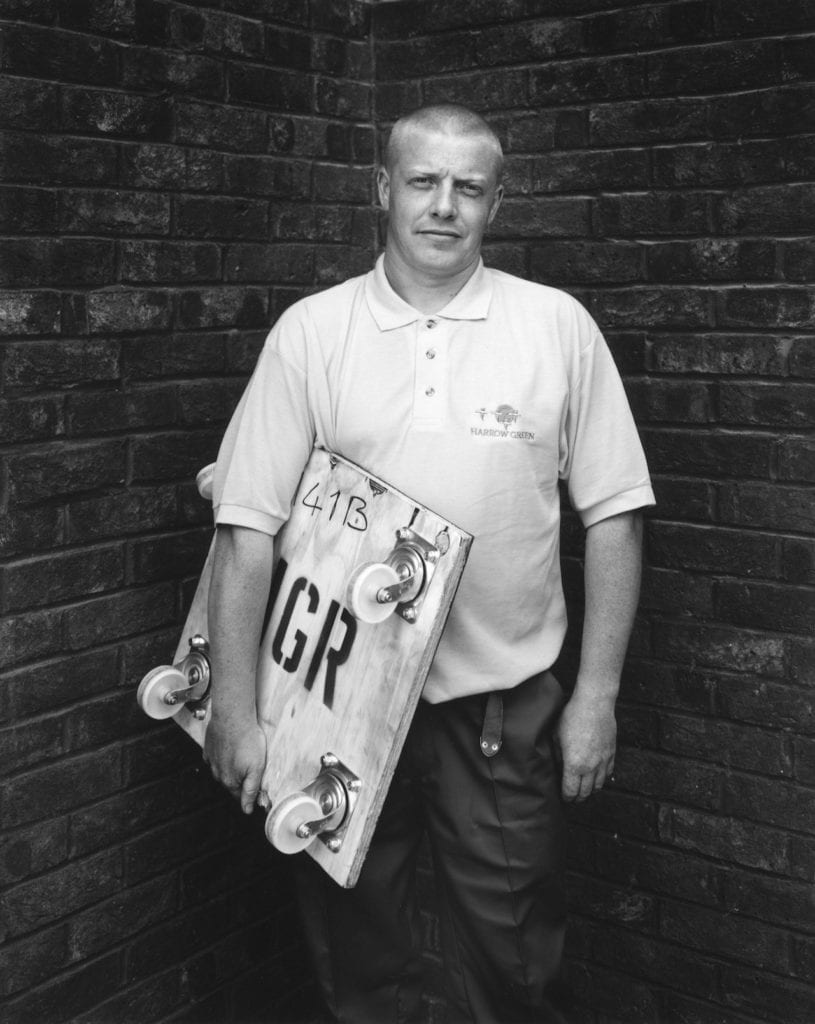

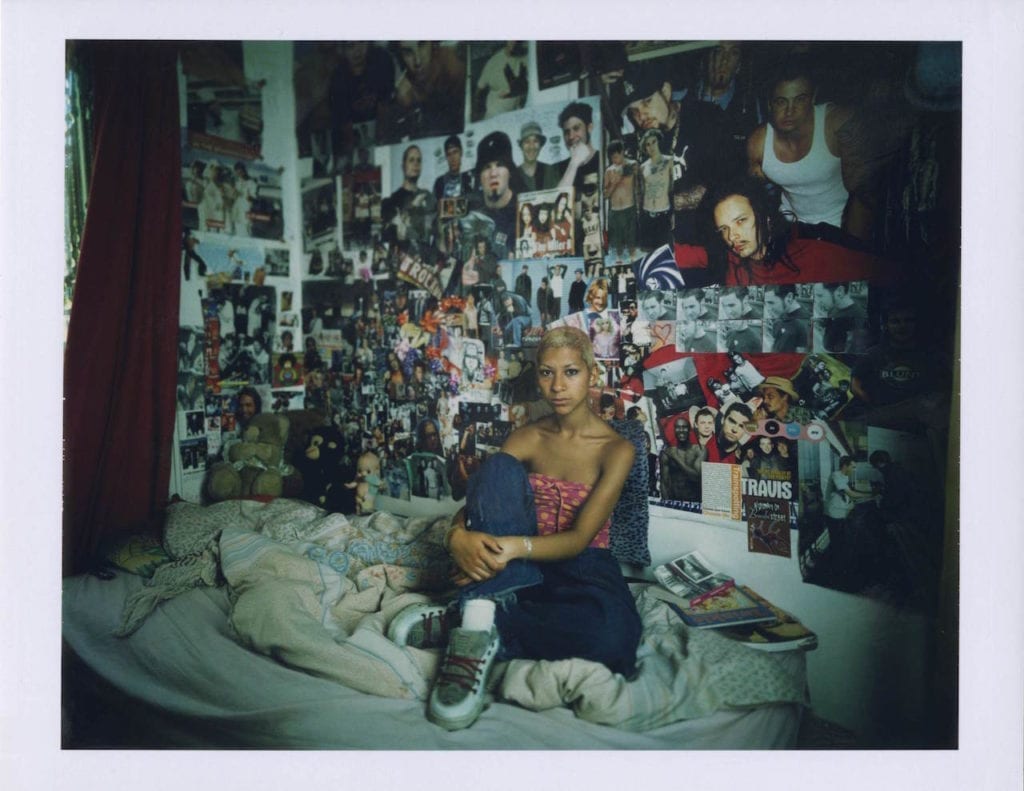

Just as Ed caught the dignity and bravery of the peace protesters, he went on to make portraits of numerous groups of people throughout his life. All his photographs exhibited his love and understanding of people in both their work and domestic settings. August Sander was Ed’s favourite photographer, and it’s the materiality and specific placing of people in their social space in Sanders’ photos that is echoed in Ed’s approach to portraiture.

He was enormously generous with his time with everybody he met, and this is reflected in his portraits. He wasn’t searching for chinks in anyone’s armour, he wanted to understand other people both in life and in his work as a photographer. When you look at all the different sets of portraits on his website www.edwardbarber.net you find that every photo is about trying to portray that person as they are, whether they are teenagers in the series 15-18: Teenagers in their Rooms or shipbuilders in Shipyard.

I taught with Ed for a period at north East London Polytechnic in the 1980s and I witnessed at close hand how he gave everything he had in terms of knowledge and encouragement to the students. He was happy to be making his way as a photographer and lecturer, rather than being desk-bound in accountancy where he started life, and this enthusiasm and openness to all stayed with him all his life.

He went on to teach at the University of the Arts London from 2003-2012, becoming the director of programmes for Fashion Photography at the London College of Fashion and running the unique BA (Hons) Fashion Photography course. In his later years he worked closely on a number of projects with his wife Danielle Inga, including Resolve: An Intimate Survey of Work.

He is survived by his wife Danielle Inga and his two daughters from previous relationships, Sonya and Nina.