Art historian and film director, James Crump, reclines on a plush, crimson sofa, which appropriately compliments s backdrop of a fiery red image of land artist, Robert Smithson’s, Spiral Getty (1970). It is the devilish poster for Crump’s new film Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art.

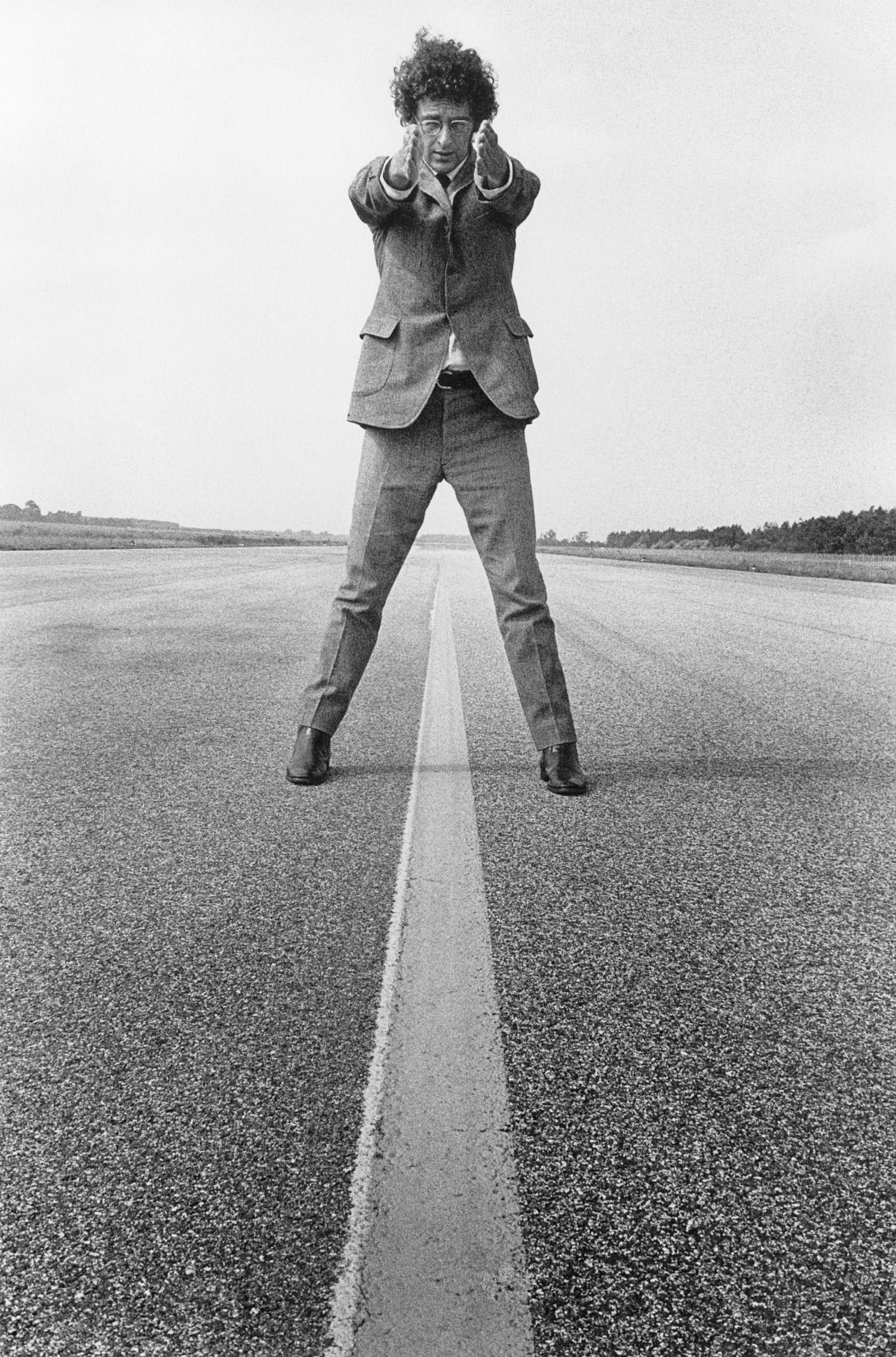

The documentary honours four pioneering figures of the earthworks movement in the 1960s and 70s; Michael Heizer, Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson and his wife, Nancy Holt.

The group are bound by their desire to make art that surpassed traditional painting and sculpture and their ambition to construct installations that encapsulated both history and modern science. They rejected the containment of the art gallery as an exhibition space, seeking a much larger canvas to work upon.

“The phrase Troublemakers comes out of my interview with Germano Celant,” says Crump of the renowned art historian interviewed in the film. “They were stirring up trouble, they were stirring up things and they were challenging traditional norms. I think the word ‘troublemaker’ is another phrase for taking up a critical position on what’s going on. Resisting the status quo.”

The film illustrates the land art movement with an in-depth examination of four of the most notable works corresponding to each artist. As we are taken through, chapter by chapter, character by character, it becomes apparent that with their immersion into the environment came a necessary understanding for the unpredictable behaviour of the ‘wild’ earth.

“The closer you get to nature, the more you realise there is a balance to be struck between tampering and land art,” Smithson explains in an old interview clip. “Nature is erratic. It is not all pastoral.”

Crump interlaces clips of archival footage and original grainy black and white photography with new wide sweeping shots of how the land art survives today, inviting us to experience the incredible scale of the isolated land sculptures, as well as how they have transformed with the passing of time and weather.

“The physical, emotional and intellectual reward that you get when you visit these sites goes beyond what anyone can describe,” says Crump. “A lot of these sites deal with perception. Perception is a huge element.”

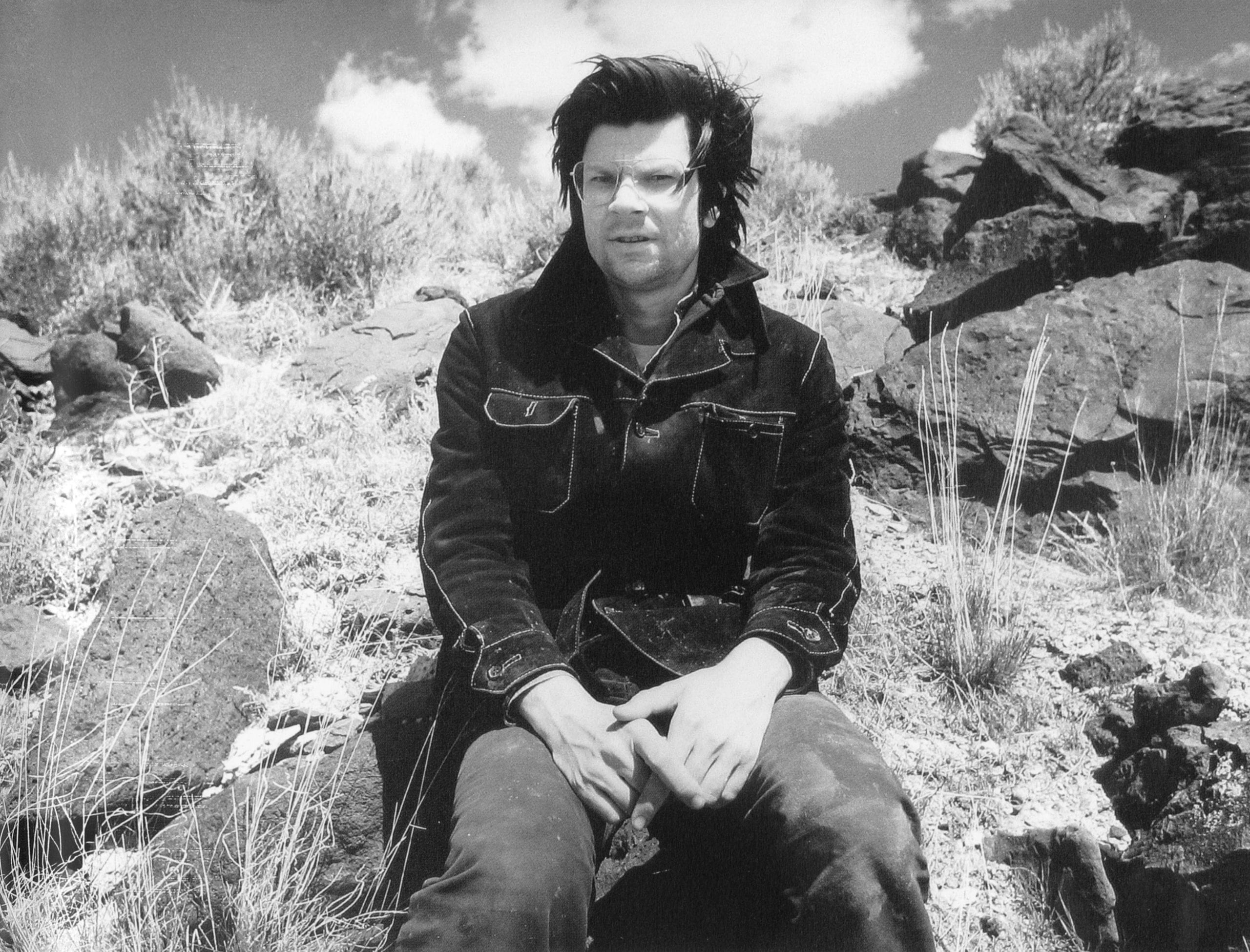

At one point, the narrative pauses on a sequence of film that leads us through Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969). The sculpture is, in the artist’s own words, an “incision” in the sandstone of the Mormon Mesa near Overton in Nevada. The camera dips in and out of the two 15 metres deep trenches, spanning some 457 metres, 9 metres wide, which sit on either side of an immense rocky canyon. Close-ups reveal large rocks that have crumbled away from the once smooth interior walls.

“Nature is slightly taking it back,” says Crump.

“I chose to use the Spiral Getty film clips by Smithson because it is a work in itself and why try to duplicate that,” the director explains. “But with Double Negative, I felt it hadn’t been shot in a way like that, so we tried to make something that was really immersive. But it was challenging to make the footage.”

Crump goes on to explain the numerous obstacles and dangers the crew encountered whilst trying to capture the perfect shots of the art works from their most regal angle.

“Having a crew inside a helicopter, shooting, and sometimes flying horizontally with a camera pointing down at the ground. It’s challenging.”

But whilst the old black and white photography of the sculptures is imperative to the telling of their story, the authors of the works rejected the medium. In the later stage of their careers, the artists became so obsessed with the aforementioned importance of perception, that the idea of displaying a photograph of their sculpture so that it could be individually interpreted by the viewer was unacceptable.

“Photography was an example of a really contentious element of land art,” says the director. “It was also to do with absolute control. Certainly with Heizer and De Maria, these artists were interested in everything about the work, from its inception, to its manifestation, to its viewership.”

Perhaps rather than immortalising their work within a still image, the land artists instead grappled with the challenge of making a permanent physical mark on the earth’s surface. Although faded, these ‘marks’ stubbornly remain and can be seen today by anyone who has the patience and ambition to find their remote locations.

“It’s part of the challenge and part of making the effort to go see these sites,” says Crump. “It’s part of the work.”

“My intention was to produce a film that was highly immersive and highly experiential. I also felt that the hyper-speculative contemporary art market deserves to have a story shared that re-discovers the spirit of these artists.

“I really want the younger generation to discover these artists, look at what they encountered and the challenges they had before them and see how they transcended those limitations.”

Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art is available to view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, and in selected cinemas across the UK, and on demand, from May 13.