Coincidentally, several books are set to be published this year that aspire to unlock the creative impulse. The Photographer’s Playbook, edited by Jason Fulford and Gregory Halpern, Larry Fink on Composition and Improvisation (both published by Aperture), and my own title, Photographers’ Sketchbooks (Thames & Hudson), are each attempting to locate and demonstrate lessons learned by those self-starting, artistically restless types whose careers have all been about finding a way through to the next project, the next exhibition, the next book. That blend of intuition and visual intelligence that enables someone like Paul Graham, for instance, to sniff out novel approaches to age-old photographic conundrums – like what to shoot on the most familiar of city streets – is a precious and potentially acquirable skill. Graham’s essay on how to begin a new project, Photography is Easy, Photography is Difficult, written in 2009 for his students at Yale University, is available on his website and is well worth reading.

“It’s so easy it’s ridiculous. It’s so easy that I can’t even begin – I just don’t know where to start,” he writes. “After all, it’s just looking at things. We all do that. It’s simply a way of recording what you see – point the camera at it and press a button. How hard is that? And what’s more, in this digital age, it’s free – it doesn’t even cost you the price of film. It’s so simple and basic, it’s ridiculous.”

After reminding us of the egalitarian imperatives of the medium in the digital era, Graham goes on to explain the converse of this argument; namely, that with an overabundance of photography available to us all in an instant, the quest for innovation and visual novelty becomes more elusive. So what to shoot?

“The more pre-planned it is, the less room for surprise – for the world to talk back, for the idea to find itself, allowing ambivalence and ambiguity to seep in,” writes Graham. “And sometimes those are more important than certainty and clarity. The work often says more than the artist knows.”

“The more pre-planned it is, the less room for surprise – for the world to talk back, for the idea to find itself, allowing ambivalence and ambiguity to seep in,” writes Graham. “And sometimes those are more important than certainty and clarity. The work often says more than the artist knows.”

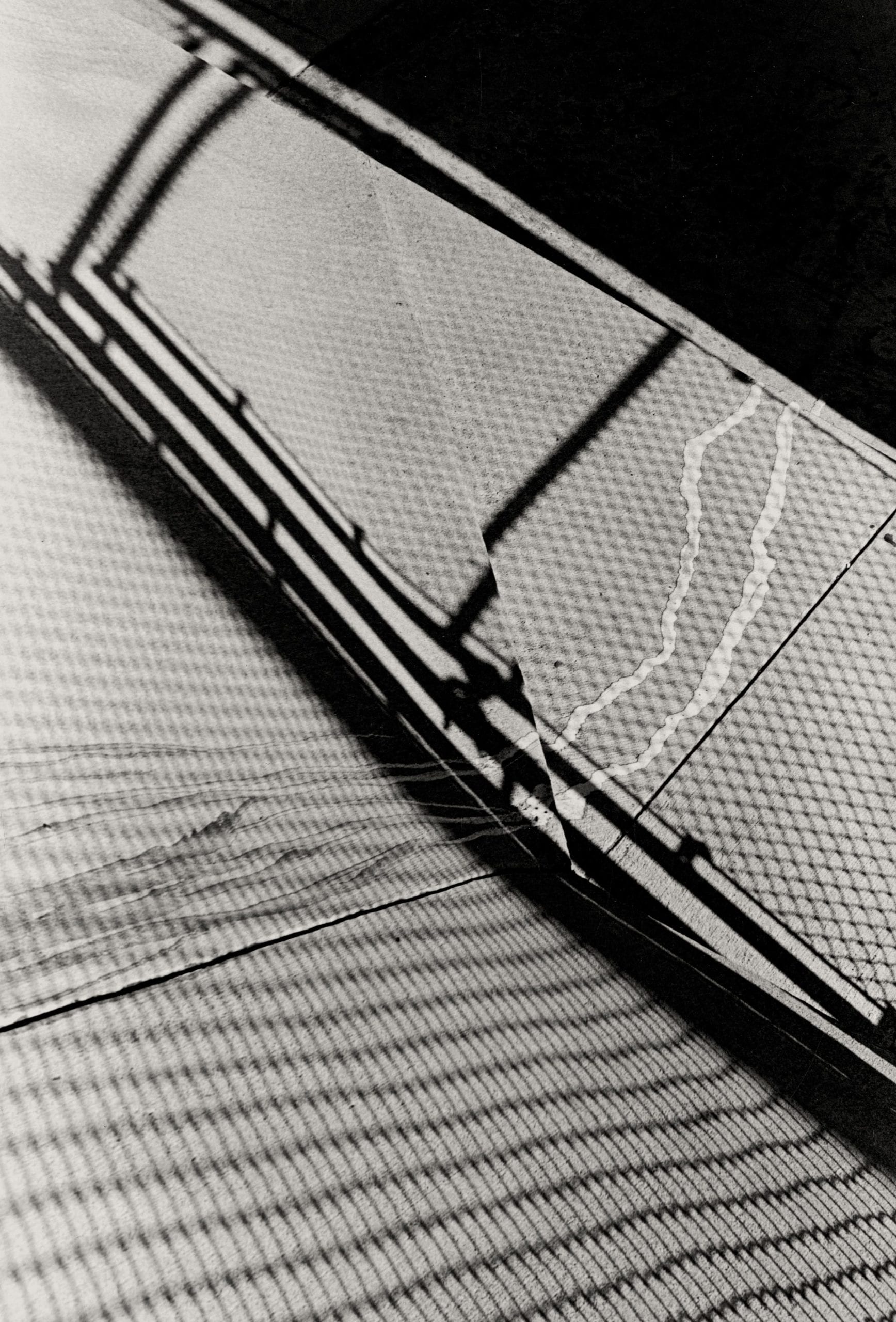

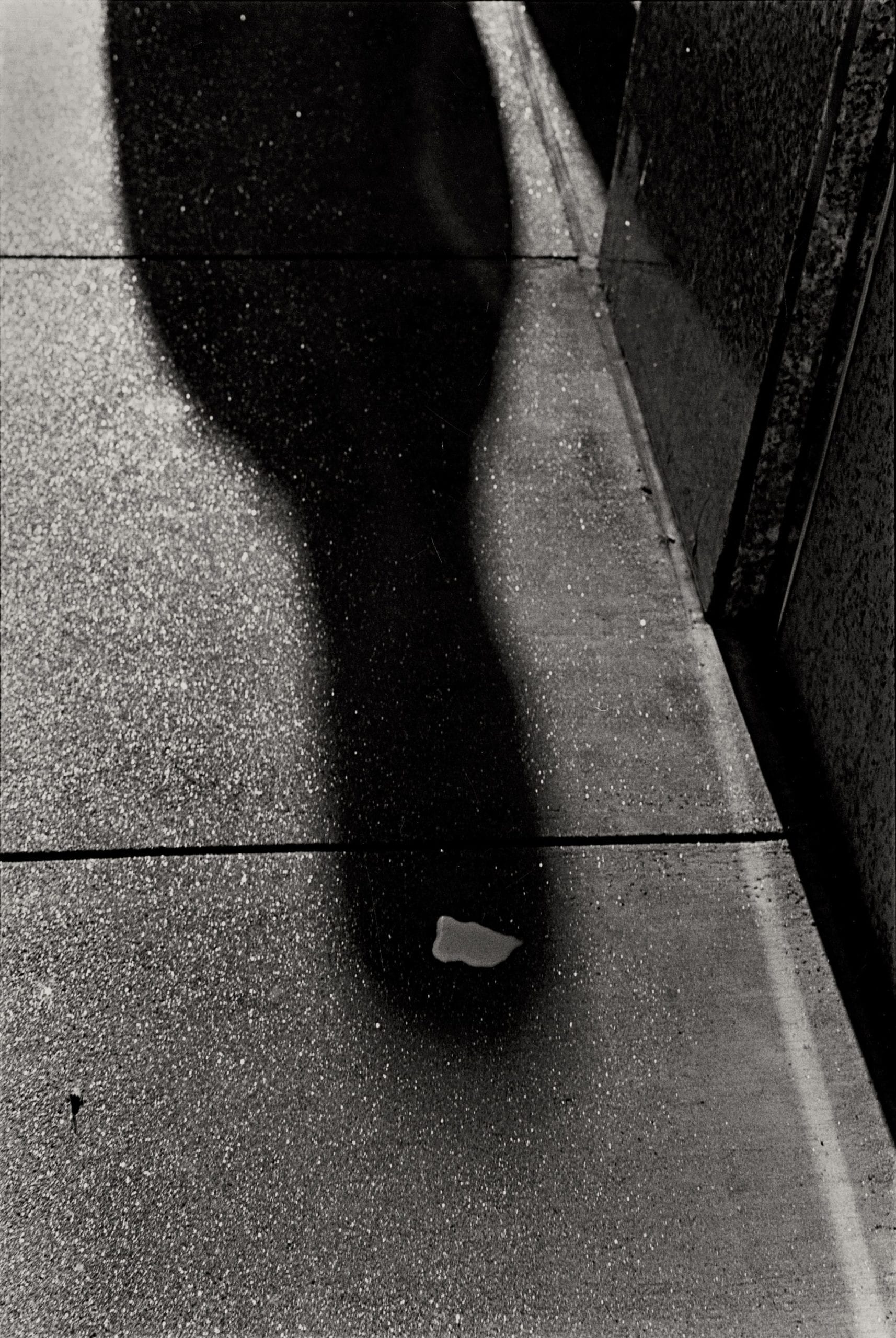

Maddock’s approach in III, which is free-wheeling and bereft of any obvious narrative, suggests that he has intuited Graham’s lesson that embracing risk and openly courting failure is a surefire way to come up with new photographic insights. “I’d spent a lot of time doing short visits to places and feeling I couldn’t work as I knew nothing about the place. I started to feel that life was too short for this attitude, that I needed to find a way to have ideas that acknowledged my ignorance and to work with that. I started to call them ‘small ideas’, and began thinking of them as something more formal and less grand [than previous projects]. In California, I realised I did know something, but that it was filmic, or culled from books, TV or other photographers and artists, and that I could say something through that. There are almost no people in III, but there’s more ‘me’. I got interested in how a fictionalised documentary approach can reach fresh truths and at the same time remain believable.”

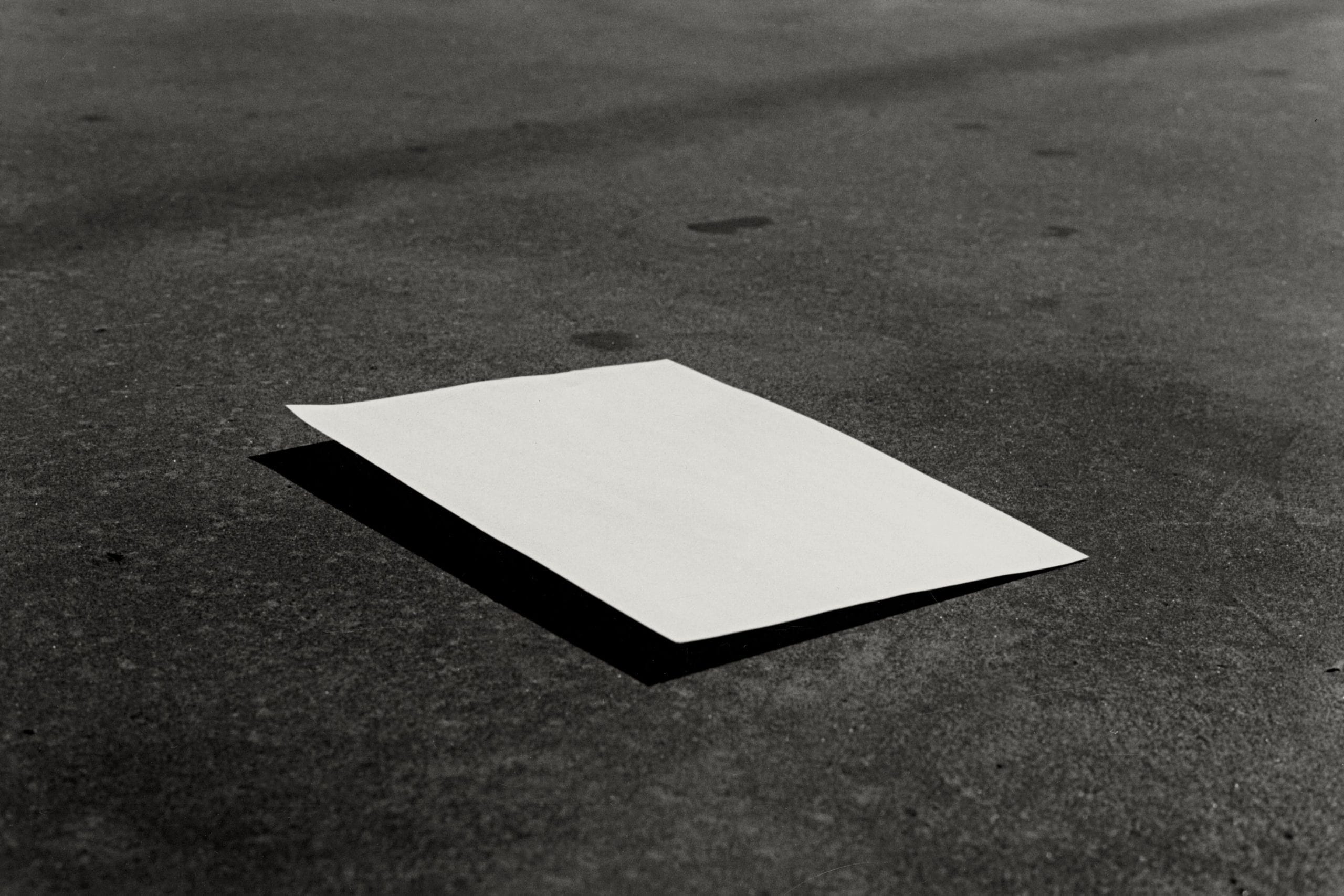

So in III we follow Maddock as he skips through California’s pockmarked city terrain, exploring its streets from the perspective of a white ping pong ball, thrown into frame this way and that, a carton of milk spilt liberally over the objets trouvés he encounters, and a blank piece of paper, the literal and metaphorical starting point of the work. Quite why he has chosen these three props and chased them around sidewalks is never made clear, but it does make for some fun and quixotic compositions.

First published in the May 2014 issue.

First published in the May 2014 issue.