The American photographer Francesca Woodman is regarded as a defining voice of her generation. Although she was a teenager when the main body of her work was completed, Woodman is now talked of as the Sylvia Plath of photography, both in terms of her cultural attitude and the workings of her art. Yet, unlike the poet Plath, Woodman remained almost completely unrecognised throughout her short, tragic life.

Indeed, her rejection from the established industry of the time may have contributed to her horribly sad death. In the autumn of 1980, at the age of 22, Woodman was forced to move in to her parent’s home in Manhattan after surviving a suicide attempt.

The adopted New Yorker, who had started her life in the frontier town of Boulder, Colorado, had begun to suffer from depression, in part due to the failure of her work to attract attention. She had sent her portfolio of self-portraits to magazines across New York, and been uniformly ignored. Then, an application for funding from the National Endowment for the Arts was rejected.

© Betty and George Woodman

An acquaintance wrote of her death: “Things had been bad, there had been therapy, things had gotten better, guard had been let down.”

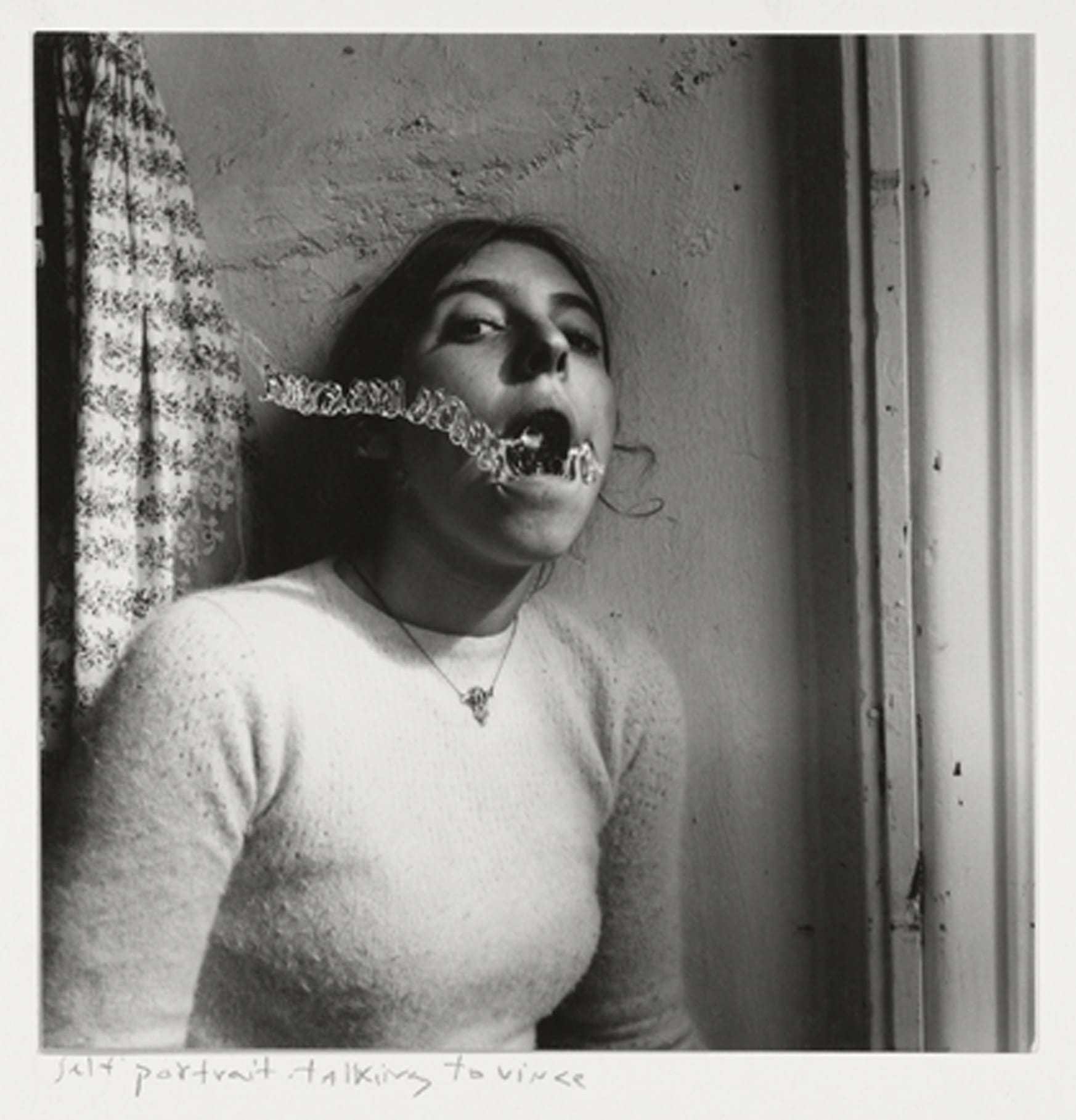

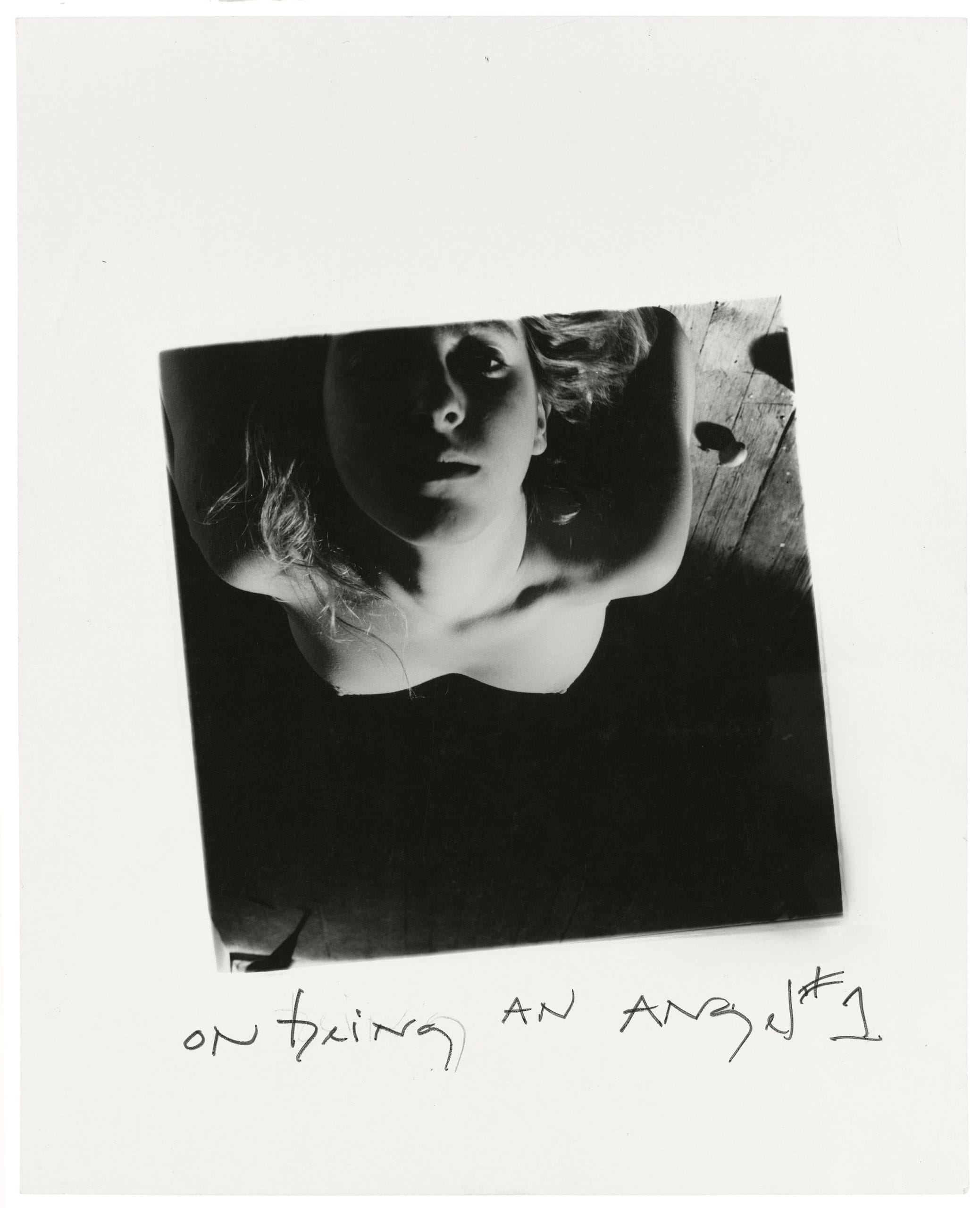

The recognition Woodman craved in life came in a rush, for she left behind an extraordinary body of work. Through largely black and white photographs, taken between 1972 and 1981, Woodman exhibited an intuitive, progressive aptitude for capturing herself and her models in rare, in-between moments – seeming at once impromptu, and yet also carefully constructed.

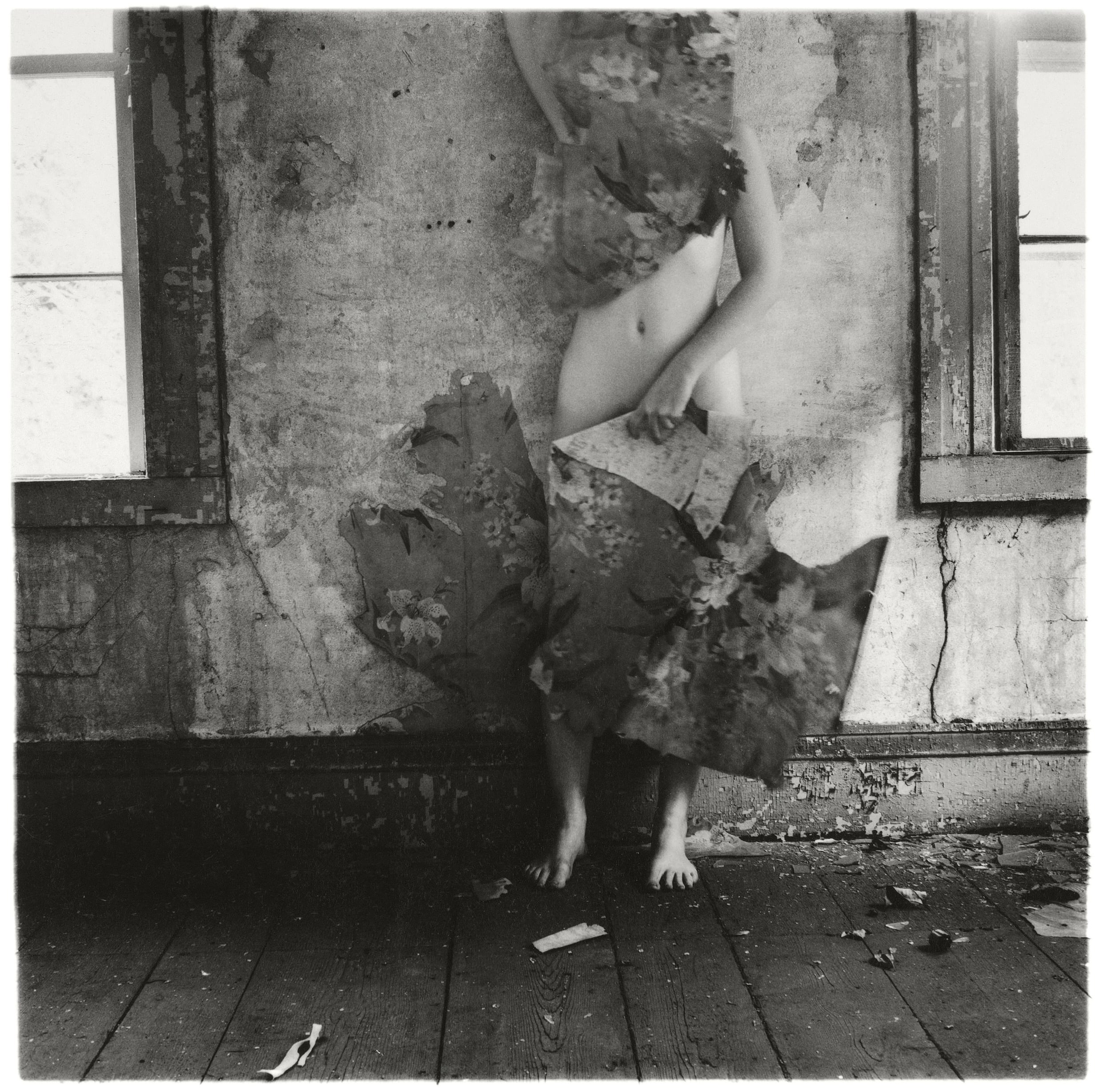

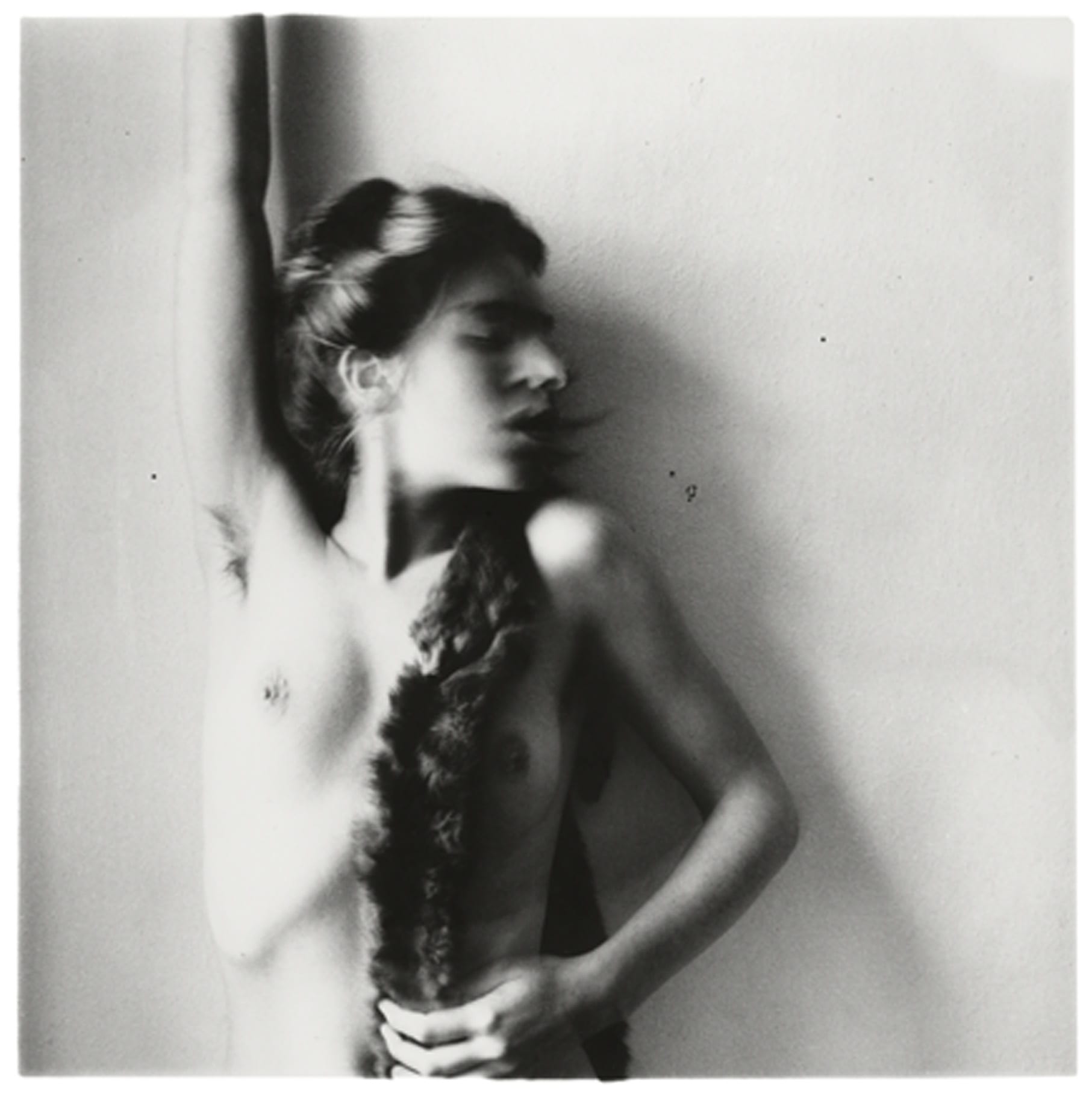

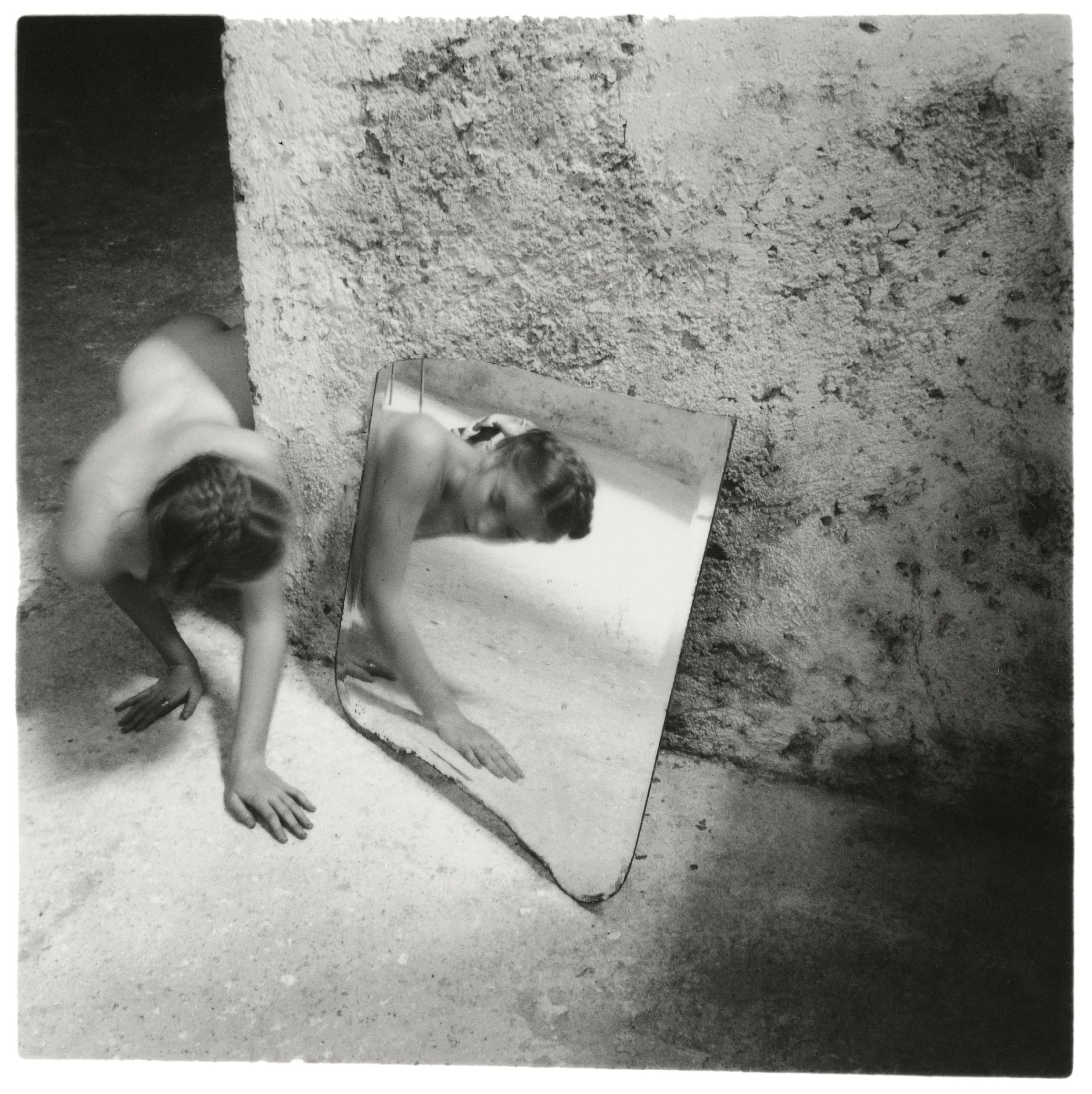

By using long-exposure techniques, slow shutter speeds and surrealist compositions, Woodman explored her subjects and set-ups with an intensity of focus and a regard for nuance rarely seen in the self-portraiture of the time – or indeed today.

© George and Betty Woodman

These themes have long been discussed by artists and art critics alike, but are perhaps even more pertinent in today’s image-conscious society, where we upload millions of self-portraits to social media every day.

Yet Woodman was hugely prolific, creating 10,000 negatives, over 800 prints, of which only 120 have ever been published or exhibited.

© Betty and George Woodman

“Francesca Woodman has been on our wish list for a long time,” says Foam curator Kim Knoppers. “She was a very gifted and talented young woman, expanding the boundaries of photography.

“From an early age, Woodman developed a signature: her body of work is very coherent, focusing on more or less one subject – herself in relation to space.

“It’s very relevant in our times to show her work. Now, we have the selfie, and people are quite obsessed with themselves – as was she. Of course, she used her body as a ‘canvas’. It’s about her, but also not about her.”

© George and Betty Woodman

Here, Woodman positions the camera above her body and pushes her chest out to emphasise the outline of her breasts. It is a photograph made to provoke, but yet it is in no way provocative.

Woodman uses her naked body. But, unlike the suggestive images familiar to us in the 21st century, her work is not primarily sexual. The viewer is instead drawn to the emptiness around her, pushed to consider not just shape of the girl, but also her performance, her position in the portrait, her process of capturing her image, the act of photography itself.

“The theme of the angel,” says Knoppers, “is as a figure that is there and also not there, because it is not human. She is, somehow, always in-between – and this in-between is very important. Woodman’s photographs are about appearance and disappearance.

“In the graveyard image, Untitled, Boulder, Colorado, 1972-75, for example, she’s disappearing in this blur of movement. She uses this technique a lot.”

© Betty and George Woodman

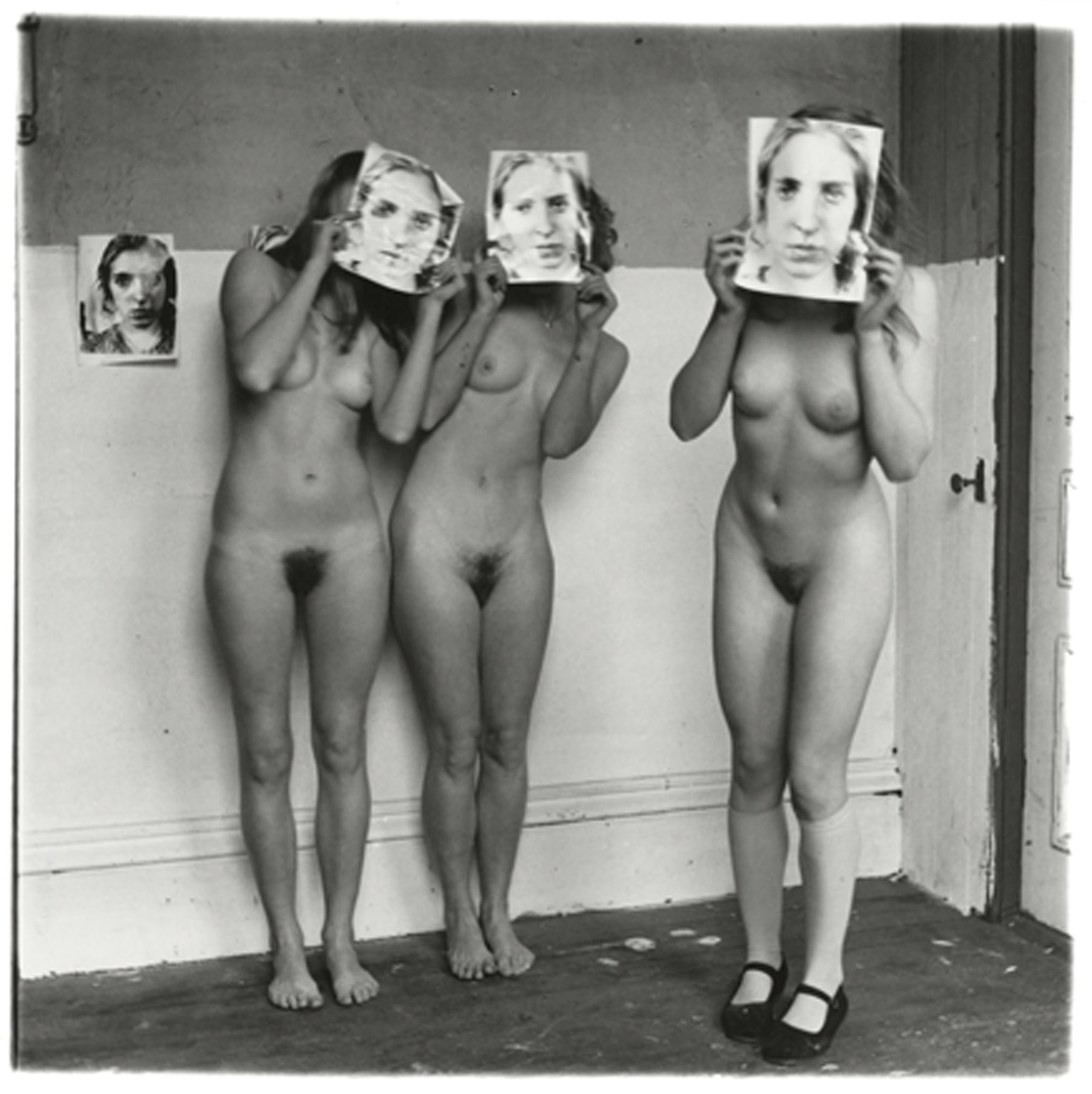

But Woodman never reveals everything: faces are blurred or masked, parts of the body hidden behind furniture, wallpaper and plants. The result is a powerful interchange between observation, self-display and mystery.

© George and Betty Woodman

“Not many people know the videos exist,” explains Knoppers, “The themes are similar to her photographs, but the video is more of a sketch. There is an even more experimental quality, but also a lesser maturity.”

© Betty and George Woodman

In one video, the viewer watches Woodman set up and shoot her well-known photograph Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976, in which she sits beside her body’s black silhouette marked onto a white-dusted floor. It’s a slow, thought-through process, but one that animates her – at the end, you hear Woodman’s voice declare: “Oh, I’m really pleased!”

Throughout her life as a photographer, Woodman showed a maturity of focus and vision perhaps best summarised by a line in her journal: “I was inventing a language for people to see the everyday things that I also see… and show them something different… Simply the other side.”

It is in her enthusiastic exploration of this other side where her enduring influence is most felt.

Find out more about the exhibition here.

All images © Betty and George Woodman, courtesy of Foam