In a re-write of a letter titled Letter to a Friend About Girls, addressed to his long-term friend and Oxford contemporary Kingsley Amis, the poet Philip Larkin wrote:

Only cameras memorise her face

Her clothes would never hang among your interests.

Larkin, attempting a more cathartic dialogue with Amis, was discussing the various women who came and went throughout the years, partners who were often ridiculed or dismissed by Amis.

Whilst these words belong to an unpublished version of the poem, and were probably not meant to be seen by Amis, it reveals Larkin’s growing fatigue with Amis’s habit of condescending him, which had come to epitomise the two men’s relationship.

Larkin accepts his female partners are less attractive, less desirable, than Amis’. And yet, in writing ‘only cameras memorise her face’, Larkin, usually so apathetic, displays an ability to be both disparaging in his attitude and decisive in his willingness to preserve these women on film.

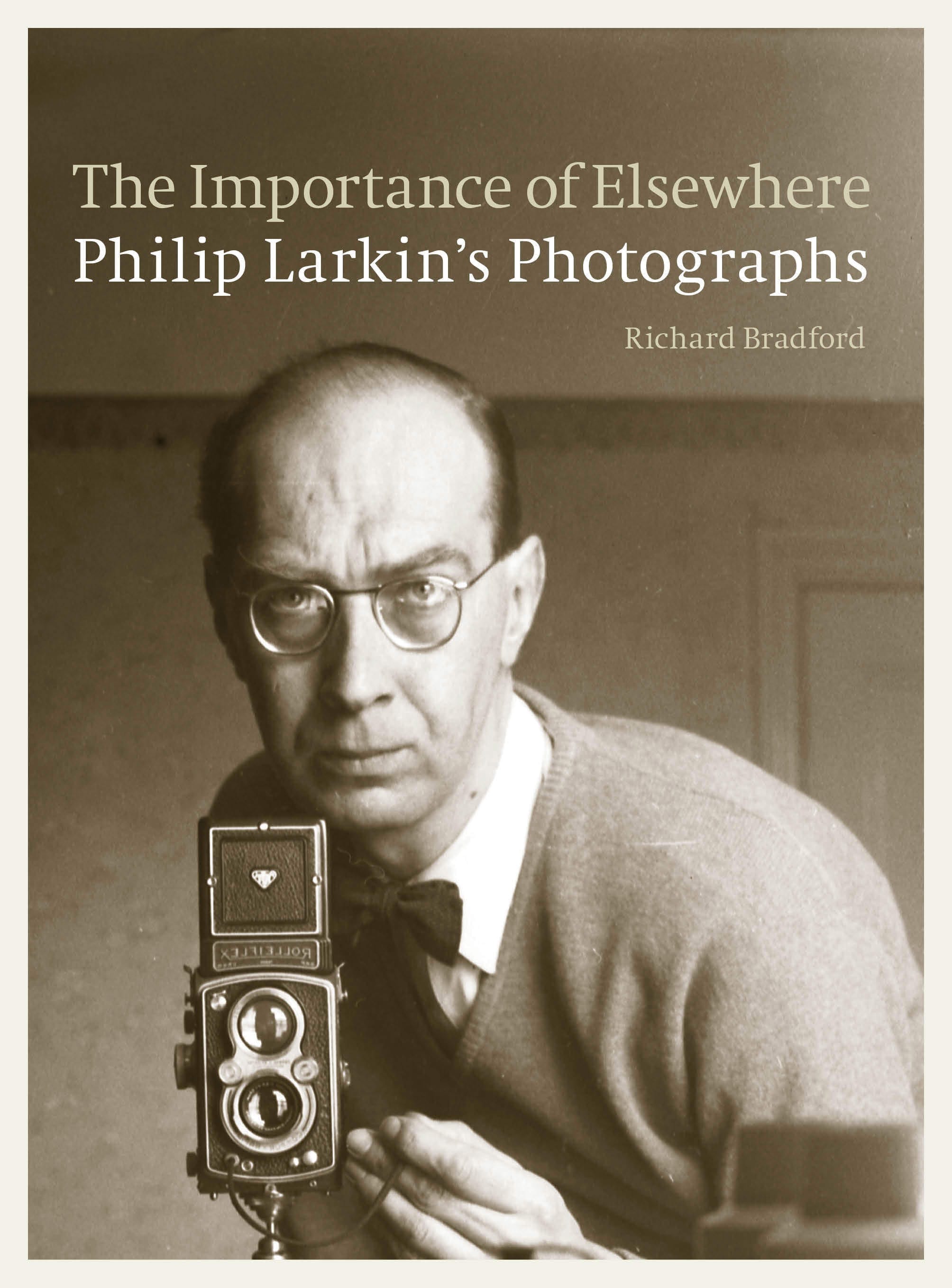

In The Importance of Elsewhere, a new photobook that explores, for the first time, Larkin’s active life as a photographer, we find a much sought after adjunct to Larkin’s provocative verse on the subject of woman and relationships, a lifetime preoccupation for a man often quoted for his misogyny.

Of Larkin’s five thousand prints and negatives kept in the archives of the Hull History Centre, in which university Larkin held his final librarian post from 1955 until his death, lecturer Richard Bradford has drawn on a selection of stills that at once uphold and challenge our preconceptions of one of the more controversial post-war writers.

Of Larkin’s five thousand prints and negatives kept in the archives of the Hull History Centre, in which university Larkin held his final librarian post from 1955 until his death, lecturer Richard Bradford has drawn on a selection of stills that at once uphold and challenge our preconceptions of one of the more controversial post-war writers.

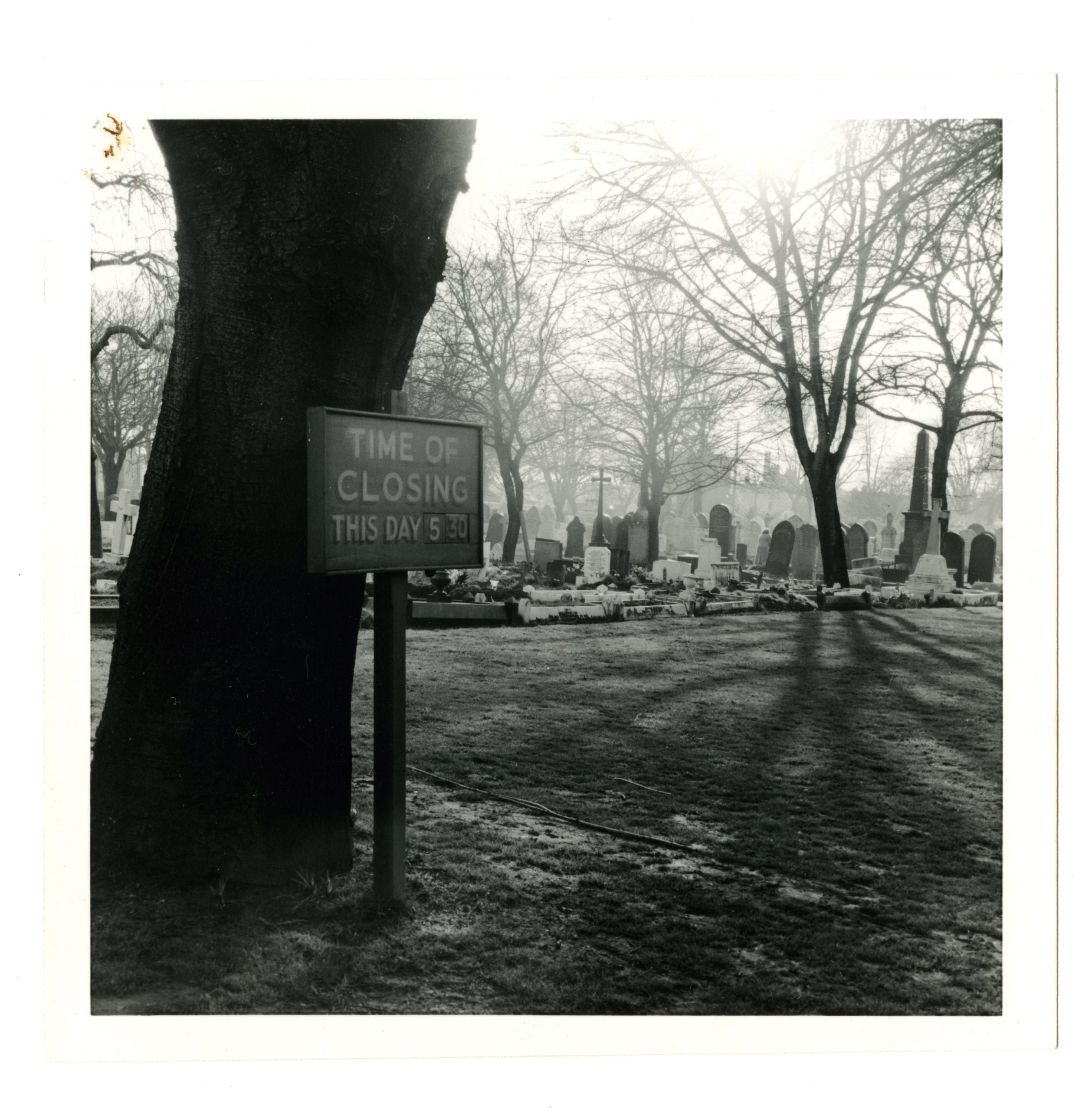

The unresolved conflict in Larkin’s photographic yearnings, as in his verse, is between life in all its mundane, inert being, and a more stylised, heightened impression of reality – an attempt to find romance in his drab surroundings and wasted days.

Monica Jones, his most trusted female confidante and intellectual equal throughout the years, is photographed in a white dress, delicately bathing in the English sun of her flowery garden in Leicester. Larkin’s relationship with Monica was anything but trouble free, and yet here she appears like a woman straight out of the pages of a D.H. Lawrence novel.

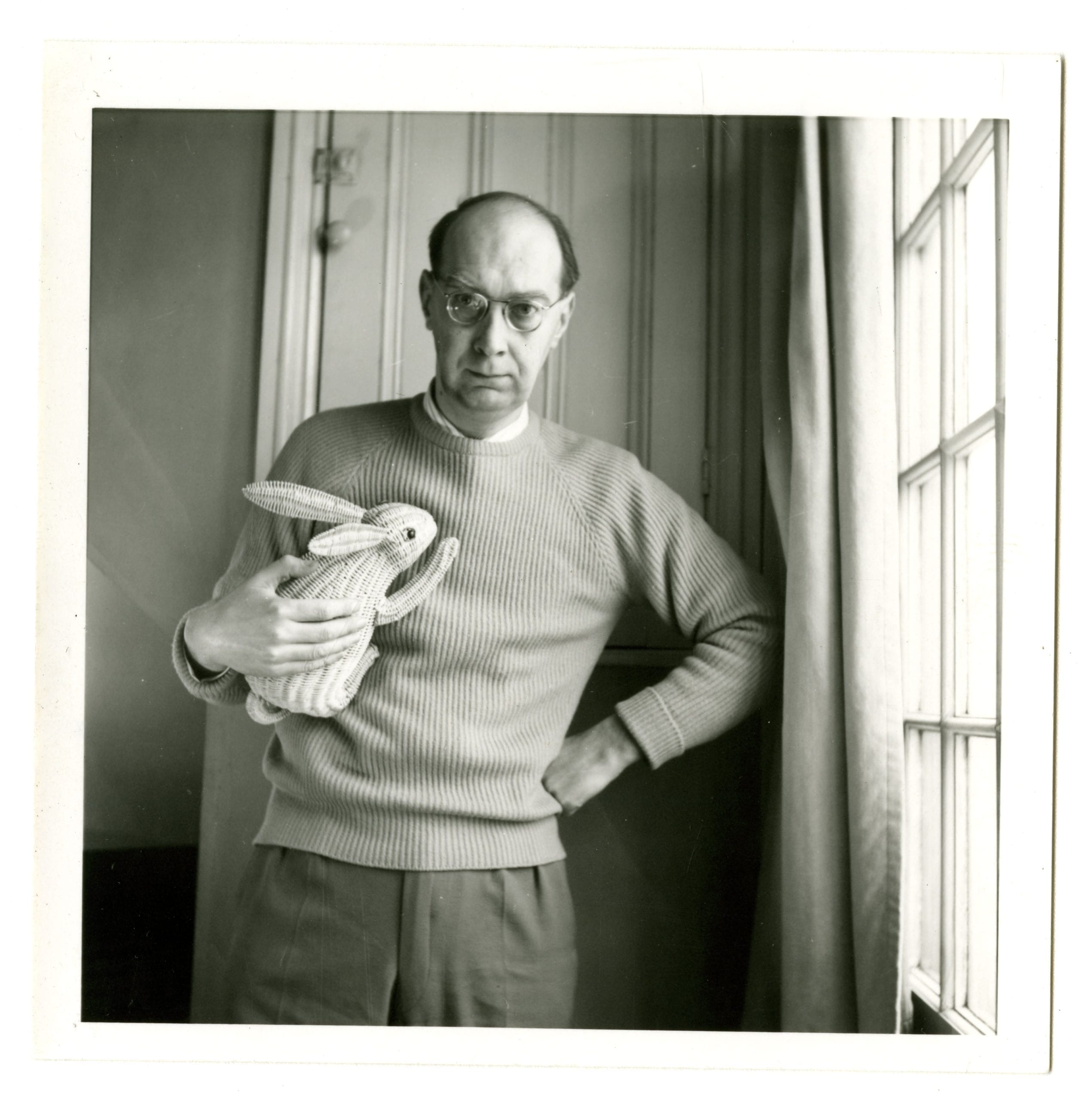

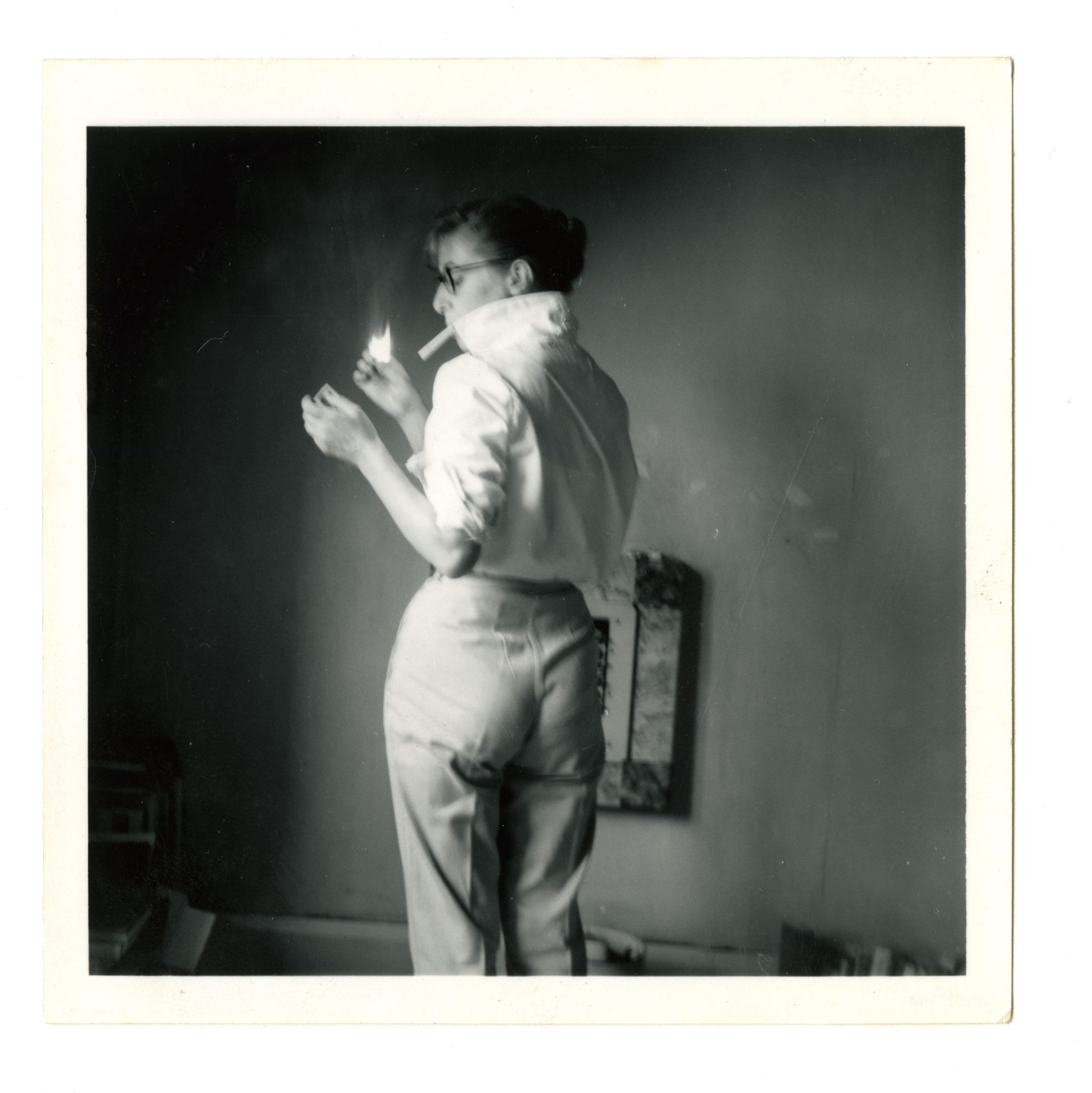

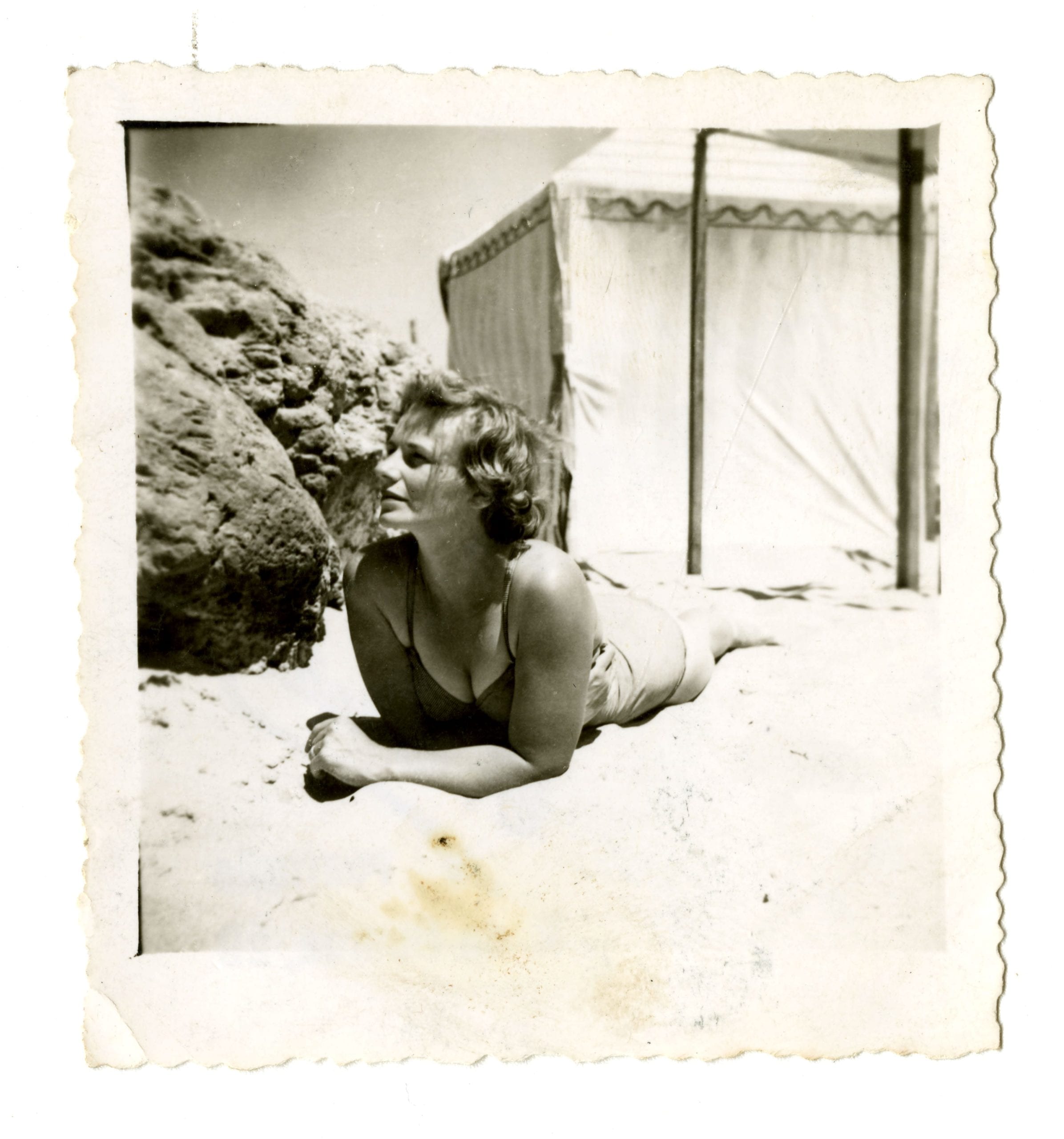

There is a quiet obsessiveness in Larkin’s portraits of his varied, often overlapping lovers. Some are almost fetishist – the same pose repeated, and presumably encouraged by Larkin, in the imitation of a 60’s Hollywood pin-up, poised on the edge of the bed or shot provocatively from behind. Others employ the same sly precision of his self-portraits – we feel the presence of the photographer through his arrangement.

One self-portrait, taken in Scotland, with Monica’s reflection visible in the window behind Larkin, feels like a particularly droll composition – a nod to all the women the man who declined the Poet Laureate kept in the shadows throughout his life.

Whilst Monica earns herself a more discerning profile in front of the camera – her combative nature and knowing stare displaying an innate confidence in having got his attention – others fare less well. Maeve Brennan, the ordinary Roman Catholic girl, is documented in less sophisticated ways, the day’s excursion often providing the backdrop to her happy and stoical poses, much as you might photograph your mother.

But it is Hilly, Amis’ long suffering wife, and occasional pen pal of Larkin, who is captured with the most complexity by the amateur photographer.

Perhaps in her domesticated and less sexualised role, Hilly is more comfortable as a subject in his Rolleiflex experiments. The dynamic gives Larkin added sight: her melancholic resignation laid bare.

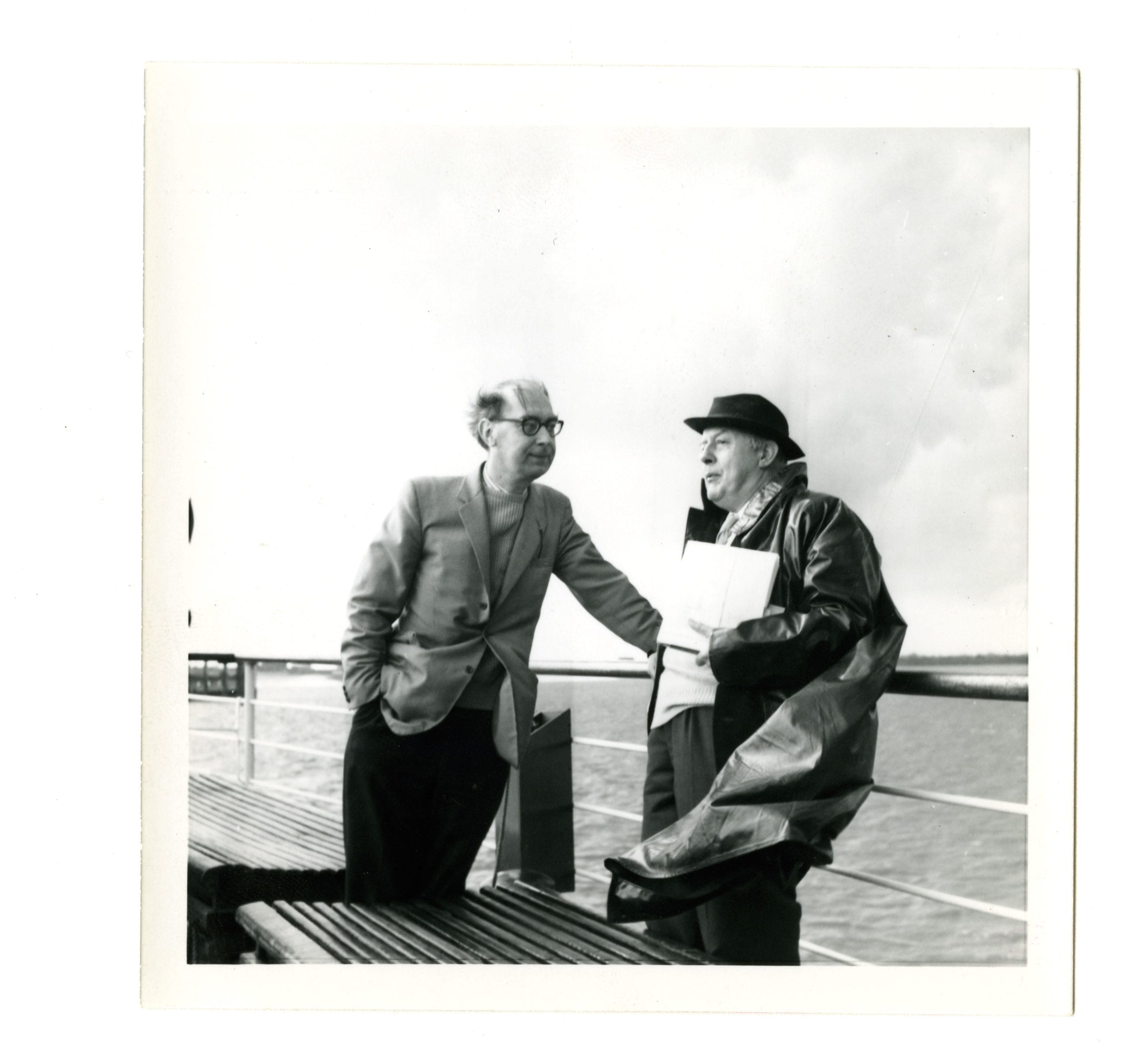

In an echo of another marital photo of friends, in which Larkin inserts himself between Patsy Strang and her cuckolded husband in a rather calculated way, Larkin stands between the Amis and Hilly in London, his hand placed on Hilly’s shoulders, at once comforting but also encouraging a strange angling away from the shot – a myopic attempt to capture the misery of her marriage, maybe, or a humane clarity on the condition of love?

He stands like the master puppeteer – one whom thinks himself invisible, possibly even above it all, perhaps not believing he’ll still be there once the photo is developed.

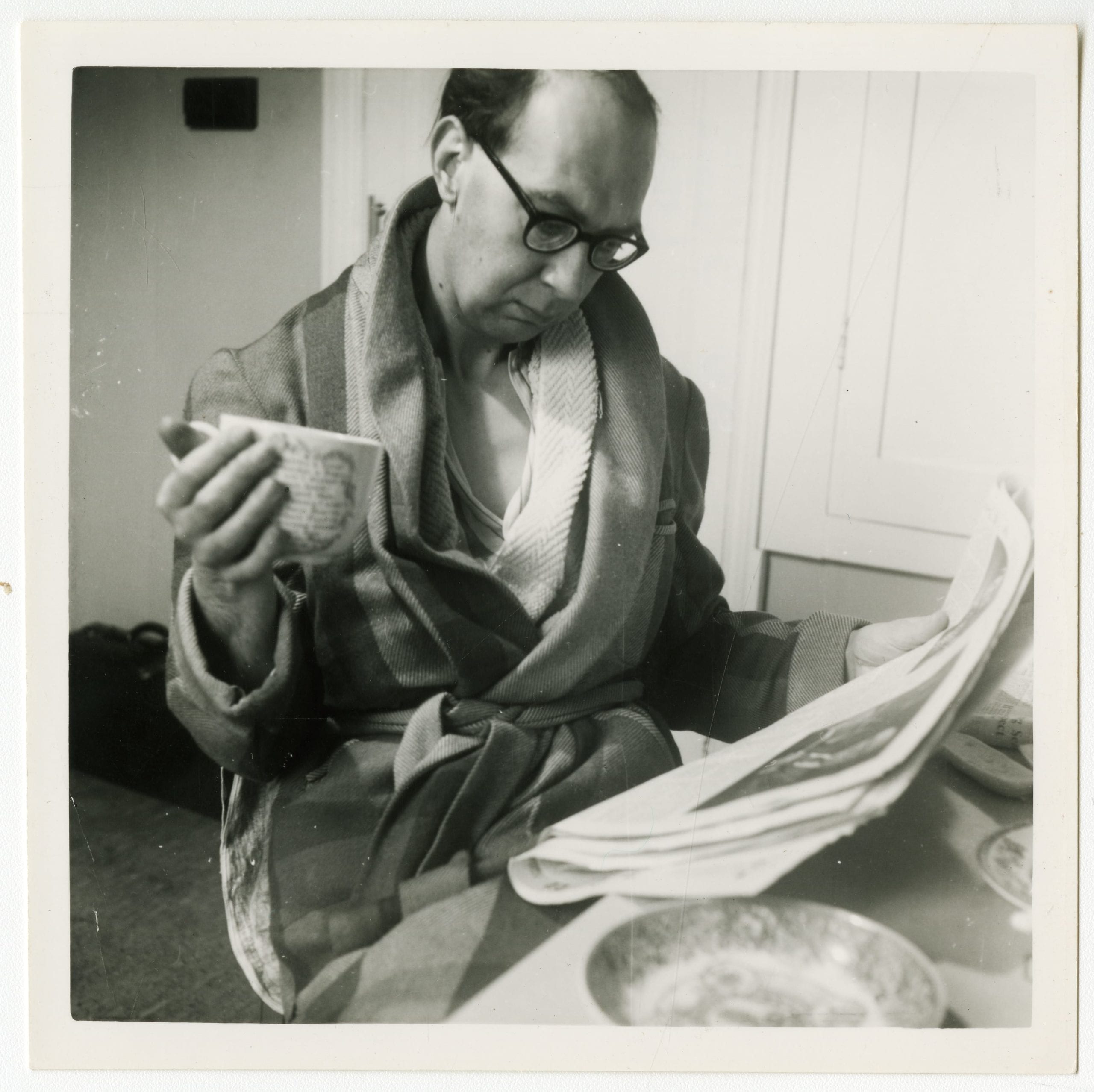

As in all his endeavours, there is an ongoing self-improvement to the work. As Mark Haworth-Booth notes in his introduction to the book: “Several prints were inscribed by Larkin with technical data and record experiments from his earlier years.”

Even in his incessant cropping, voyeuristic though it sometimes seems, Larkin is anticipating the ability to zoom; to get closer to the fleeting, the nuanced. His desire at one time to write a novel of ‘pure vision’, as told to the painter Jim Sutton, figures here too in his preparatory stage management. As Bradford writes: “Often, Larkin placed a large mirror behind the timed camera so that he could form an expression that perfectly suited his desired shift between transparency and something more enigmatic.”

Bradford suggests that Larkin turned to photography at a time when he was struggling to find his authentic voice as a writer. It certainly seems he didn’t really know who he was for a good while, his chaptered life and impermanent relationships revealing a constant need to re-define himself: at Oxford, he tried to distance himself from his parochial childhood by wearing ‘silk bows and waistcoats of equally loud hues’; on arrival in Belfast, having finally cut ties with Ruth Bowman and escaped his insincere marriage proposal, he writes: “Here no elsewhere underwrites my existence.”

The eponymous Elsewhere poem supporting the notion Larkin felt buoyed as the outsider, both creatively and personally. In all, it seems he cultivated a manageable intimacy with those around him, either sensing that prolonged exposure to the same person could stagnate his originality, or that the greatest combatants of his life might ultimately become his captors. As he wrote in the poem To My Wife:

Now you become my boredom and my failure,

Another way of suffering, a risk,

A heavier-than-air hypostasis.

The Importance of Elsewhere: Philip Larkin’s Photographs is published by Frances Lincoln