Protest imagery has taken on a refreshed sense of vibrancy in recent years, thanks to the rise of smartphone photography, social media and a new generation of young, politically engaged activists. But while smartphones have allowed for a wider range of representation, the rising tide of documentation has also raised all boats, including photojournalists like Natalie Keyssar who’d perhaps still be photographers in any other era. The collective appetite for dynamic photography that helps portray the raw edges of global issues has never been greater, and this sense of drama is present in Keyssar’s work, which has been seen in publications like Bloomberg Businessweek, California Sunday, The Fader and The New York Times.

Newly signed by international photo agency INSTITUTE, on her website she describes herself as “primarily [focusing] on youth culture, activism, and class”, and in recent months Keyssar has focused her lens on scenes of activism and protest around the world. We caught up with her over email to ask what compels her to cover these issues.

Your recent work has focused on the texture of protest, specifically relating to post-Chavez Venezuela and the Black Lives Matter movement. What does protest mean to you? What about it appeals to you as a photographer?

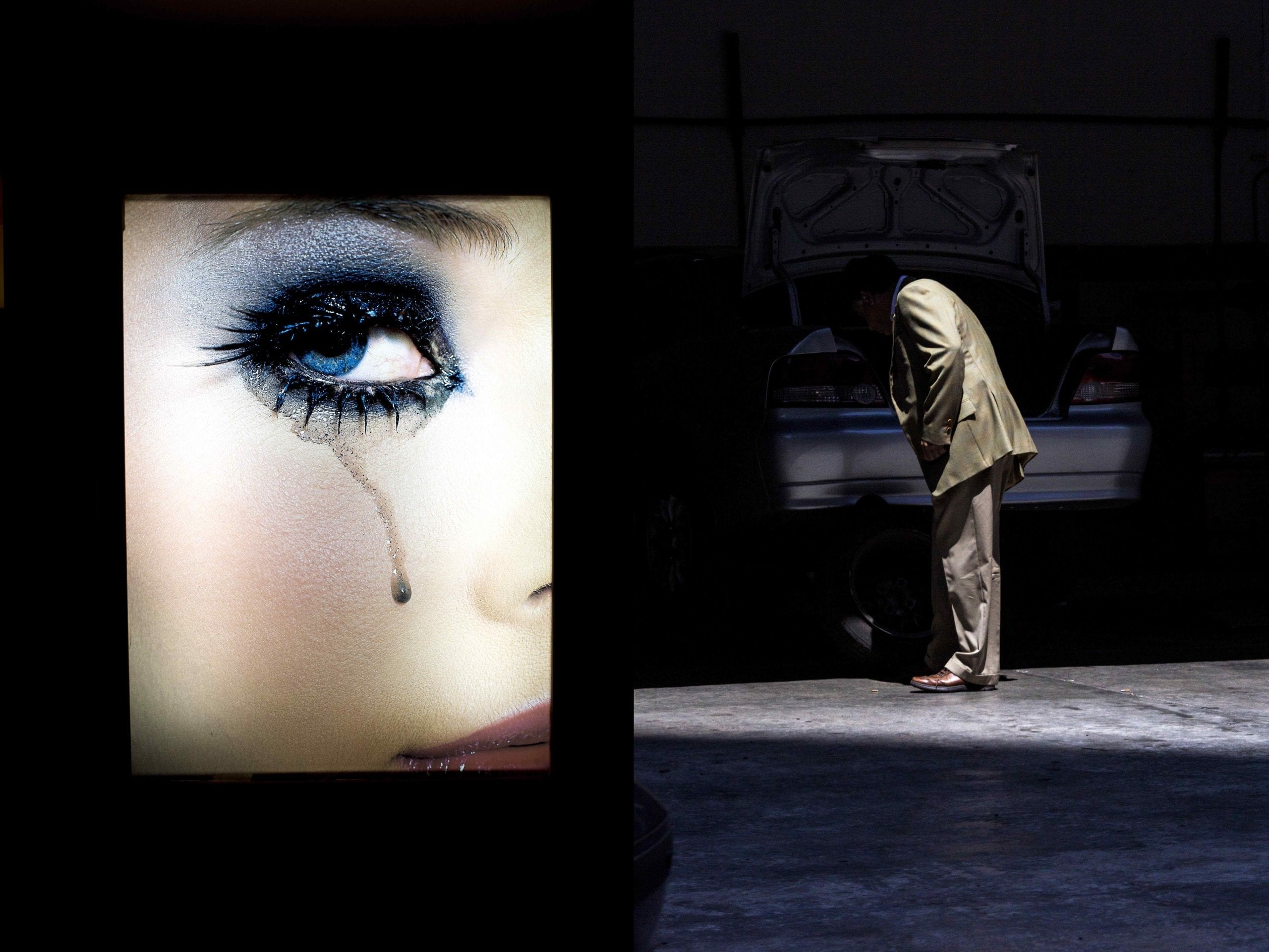

For me, protest is all about symbols. We live in a society where the structure of power can often seem intransigent – economically, legally, in terms of civil rights, etc. Protest is a symbolic interaction between the people and the state. That doesn’t mean there aren’t real consequences or real violence – in the case of Venezuela for instance, there were over 43 deaths in the 2014 protests. People are caught up in our daily routines and political protest is this phenomenon of hitting pause and challenging the status quo. In a world of social norms and social media, protest is a very real, very human interaction, where someone decides that an injustice is worth yelling about, worth standing out in the cold, maybe worth getting tear gassed – [even] worth dying for.

As a photographer I find protest to be an interesting landscape to explore issues, social change, and human rights. There are many tropes in protest photography. I’ve heard editors say “the wires have this covered” dozens of times, as though there’s only one type of image to make in a protest, pure documentation and thats it.

But the moments when activists are clashing with representatives of the state are incredibly rich and multifaceted to me. I start with the protests as the epicentre of an important issue, and began to track the issues back to their routes in various forms – trying to collect and integrate the human stories that lead to these moments where everything goes crazy – so you can put the issues in context visually. I find the ritualised interactions between police, protesters and the media really fascinating. Covering many protests makes me think about the ways they are all the same, and the ways they are each unique.

Protesters can sometimes be wary of journalists and photographers – how do you gain the trust of your subjects?

In order to gain peoples trust, you have to give them yours. That means being clear about your intentions and being willing to put in the time with your subjects to reach an understanding. I think nearly everyone, especially activists, have something to say that they want heard, so giving them an outlet for that is a pretty quick way to build a relationship. A lot of protesters value commitment and are wary of journalists that come and go quickly, but more welcoming to those that they see again and again. There’s no question that sometimes the tides can turn quickly against the media in protests for a variety of reasons (often some journalists behaving disrespectfully can really poison the well for everyone) and you have to be aware of that possibility, but I find that if i put my trust in the people then they usually return it.

Right- Police lights illuminate a tree off of West Florissant Road.

What was the biggest risk you took to get the shot?

Anyone doing this type of work is taking some risks, but I’m essentially dipping my pinky toe into the day-to-day experience of someone else. I’ve definitely had a couple of scrapes, but I have lots of colleagues whose work is far more hazardous. I choose to cover some risky situations because I’m deeply interested, I don’t have to, I’m not a protester, or a cop. I don’t live in a dangerous neighbourhood. I’m just choosing to go there for a period of time because I’m interested. So some of these situations I work in are high-risk, but I don’t think about it like that because the risks to my subjects are almost always so much higher. Being a photographer often means you need to run towards trouble and not away, but I try to keep my head very clear and calm and always be aware of the worst case scenario in my decision making.

Find more of Natalie’s work here. She is represented by INSTITUTE Artists.