Portrait of Humanity provides photographers with the chance to share portraits of everyday life around…

Portrait of Humanity provides photographers with the chance to share portraits of everyday life around…

Portrait of Humanity is a unique photography award. Seeking images that capture life across the…

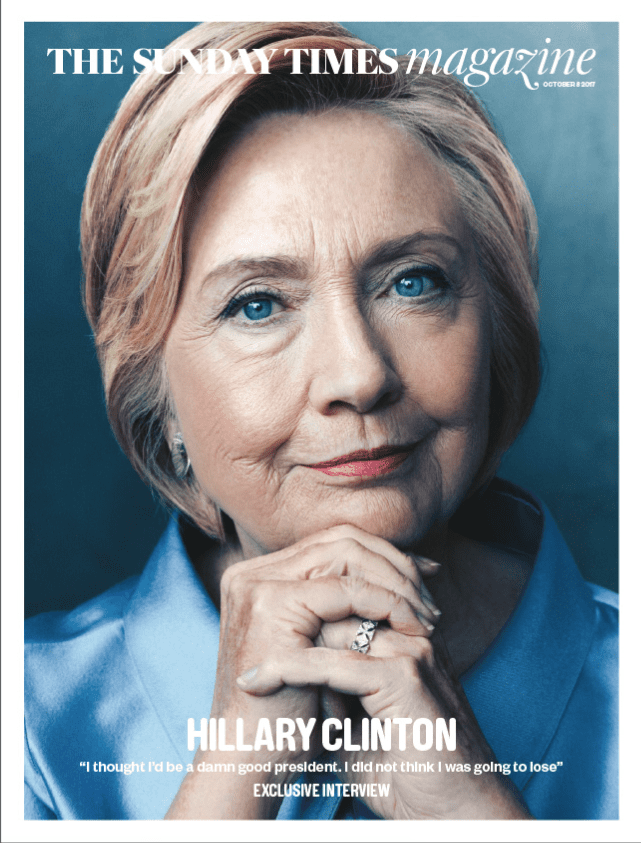

David Levene has spent many years photographing for The Guardian, and in particular for their…

Nelson Morales was seven years old when he saw a Muxe for the first time. Seeing an individual he didn’t identify as a woman proudly wearing a tiny swimsuit, fluffy feather boa and glistening sequins at a local festival, he was “shocked”, he says.

But Morales was growing up in the city of Oaxaca, central Mexico, where the Muxes are regarded as a third gender – assigned male at birth but interested in codes of dress and behaviour associated with femininity, often from a young age. Asked to photograph the Muxes community, Morales soon found himself liberated by them.

He continued to photograph the Muxes – and himself – for eight years, hoping to capture the complexity of their lives and to confront his own identity as he joined their community. His book, Musas Muxes, is published by Mexican collective Inframundo.

In the city of Oaxaca, the Muxes are regarded as a third gender. They are assigned male at birth, but from a young age they dress and behave in ways associated with the female gender.

One day, Morales was asked by a friend to photograph this gender-fluid community, and soon he found himself liberated by them. Over eight years he photographed them, and himself, hoping to capture the complexity of the Muxes lives, while confronting his own identity in the sensual and challenging space of the Muxes.

Our followers voted Iranian photographer Hossein Fardinfard’s image as their favourite of the recent Guardian…

The paradox of otherness is at the core of Maria Sturm’s You don’t look Native to me. Her subjects belong to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, the largest tribe in the region with around 55,000 members, with their name taken from the Lumber River of Robeson County. Starting in 2011, Romania-born, Germany-raised Sturm spent time in Pembroke, the economic, cultural and political centre of the tribe, photographing their daily lives. It opened up questions about visibility, identity and stereotype in the US, where Native Americans are romanticised yet often dismissed. Many tribes remain officially unrecognised, though the sense of identity within the communities is very strong.

On her first visit, Sturm was struck by two aspects. “One was that almost everyone I talked to introduced themselves with their names and their tribe. The other was the omnipresence of Native American symbolism: on street signs, pictures on walls, on cars, on shirts and as tattoos.” She attended powwows (where leaders pray to Jesus, another surprise to Sturm) and spent time with locals.

In the first of our interviews with BJP International Photography Award 2019’s judges, we meet…

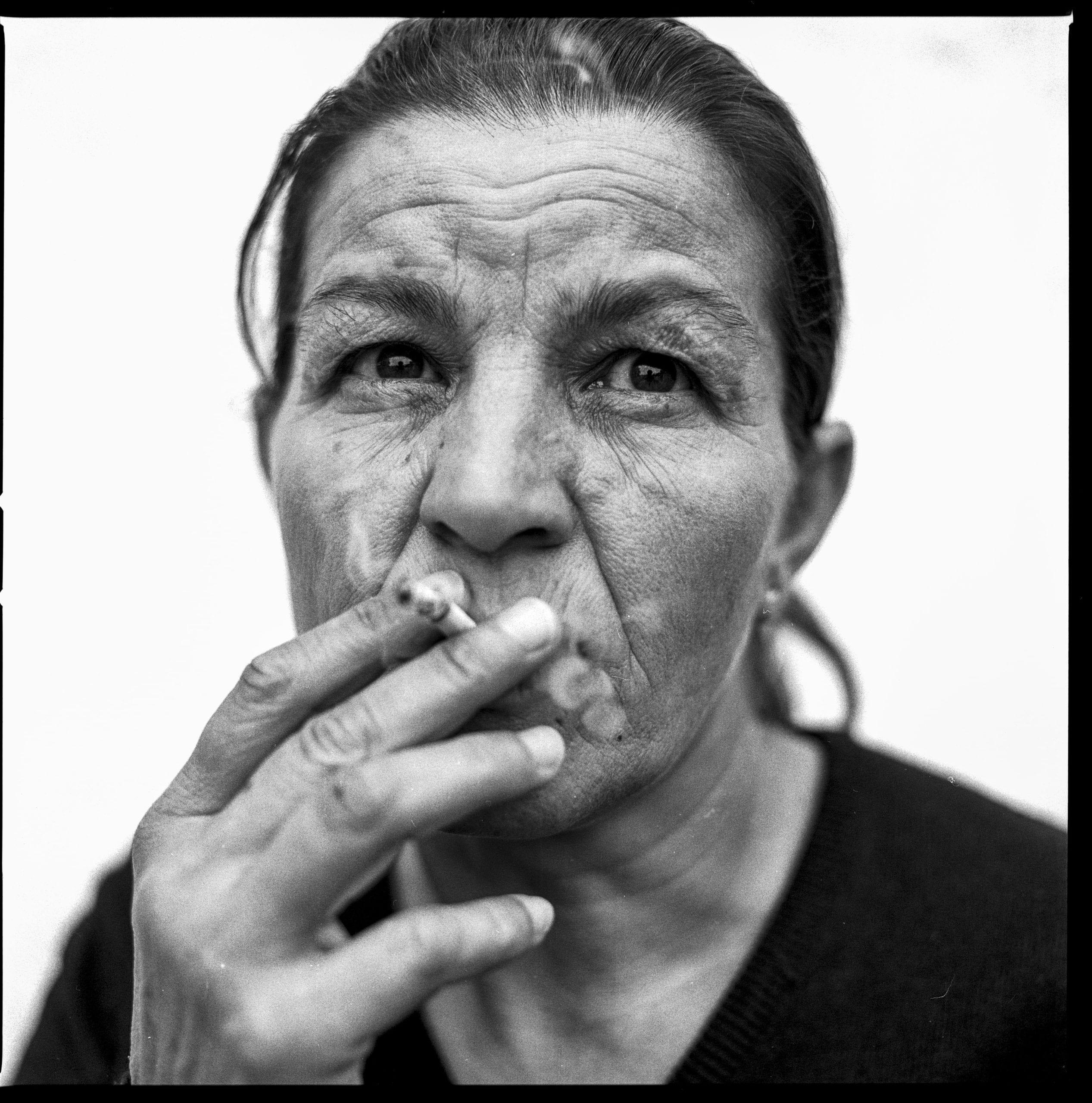

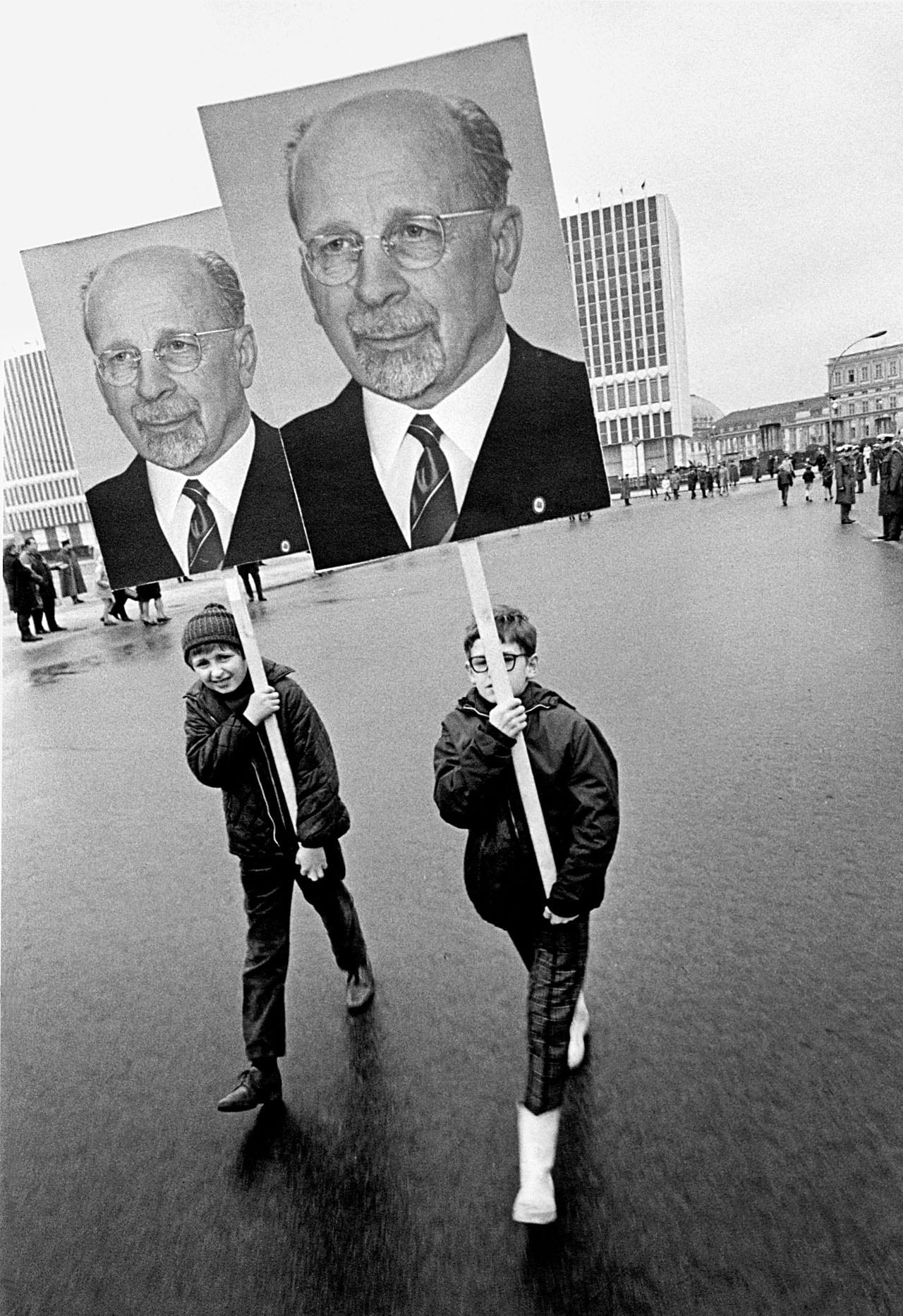

“This book….does not – and this I must emphasise – document life in the GDR [German Democratic Republic]. Rather, it shows how I saw this country and the people who lived here,” writes Roger Melis in the introduction to his book In a Silent Country, now published for the first time in an English edition.

“When selecting the photographs for this volume, I placed no demands on myself, and certainly did not try to comprehensively depict working and living conditions in the GDR,” he later adds. “…they focus on the everyday, and not on the spectacular. In my photographs, I only rarely attempted to capture a decisive, unrepeatable moment. The moments I always searched for were the ones in which whatever was special, unusual or temporary about people and things had dropped away, revealing the core of their being, their essence.”

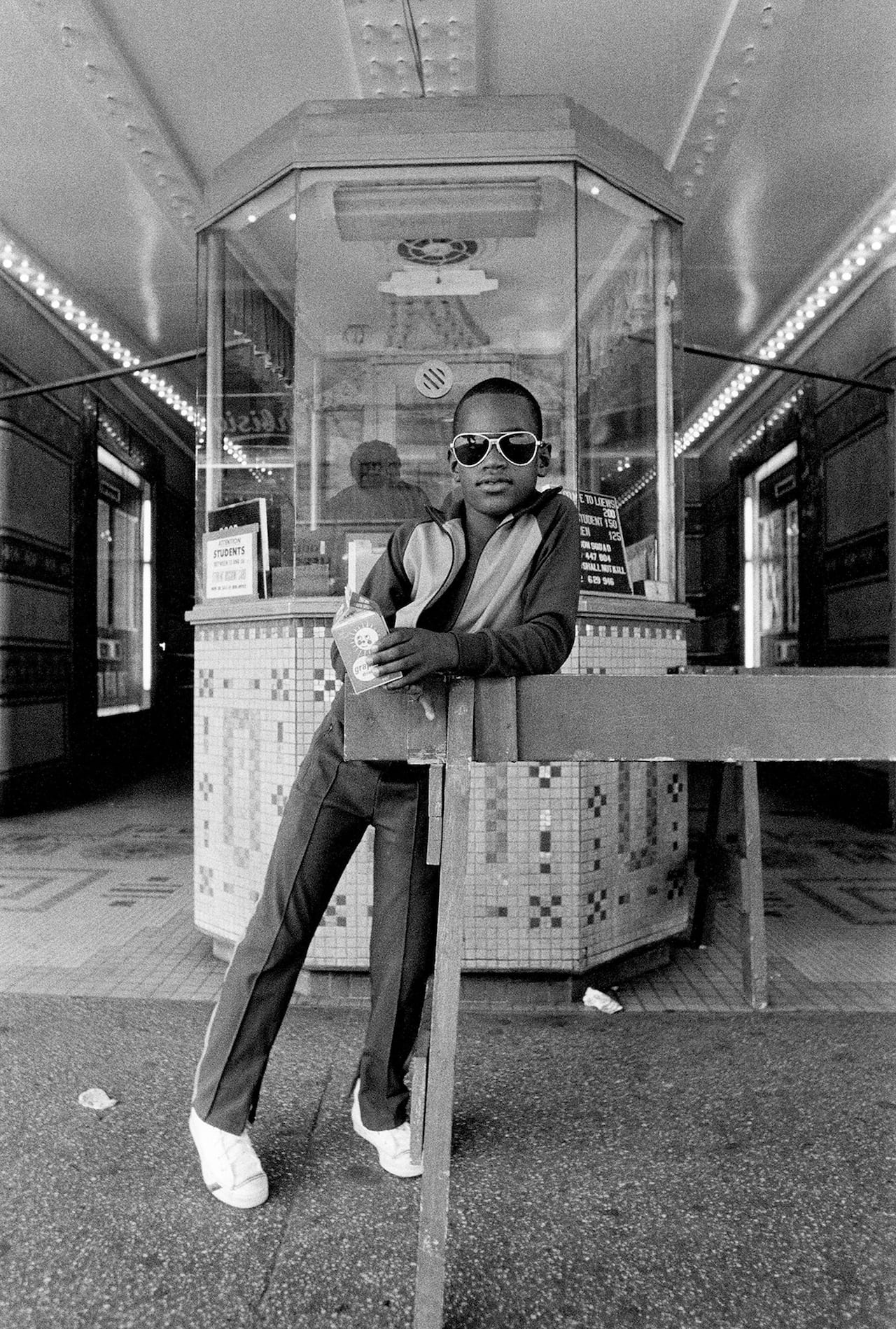

For over 40 years, American photographer Dawoud Bey has been photographing people from groups too often marginalised in the USA, seeking out stories overlooked by conventional and stereotypical portrayals.

Born and raised in New York, Bey began his career in 1975 at the age of 22. For five years he documented the neighbourhood of Harlem – where his parents grew up, and which he often visited as a child – making pictures of everyday life. This series, along with three more of his projects, is on show this month at the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto, Canad