Collaborations form a big part of some of the year’s most notable works. We have…

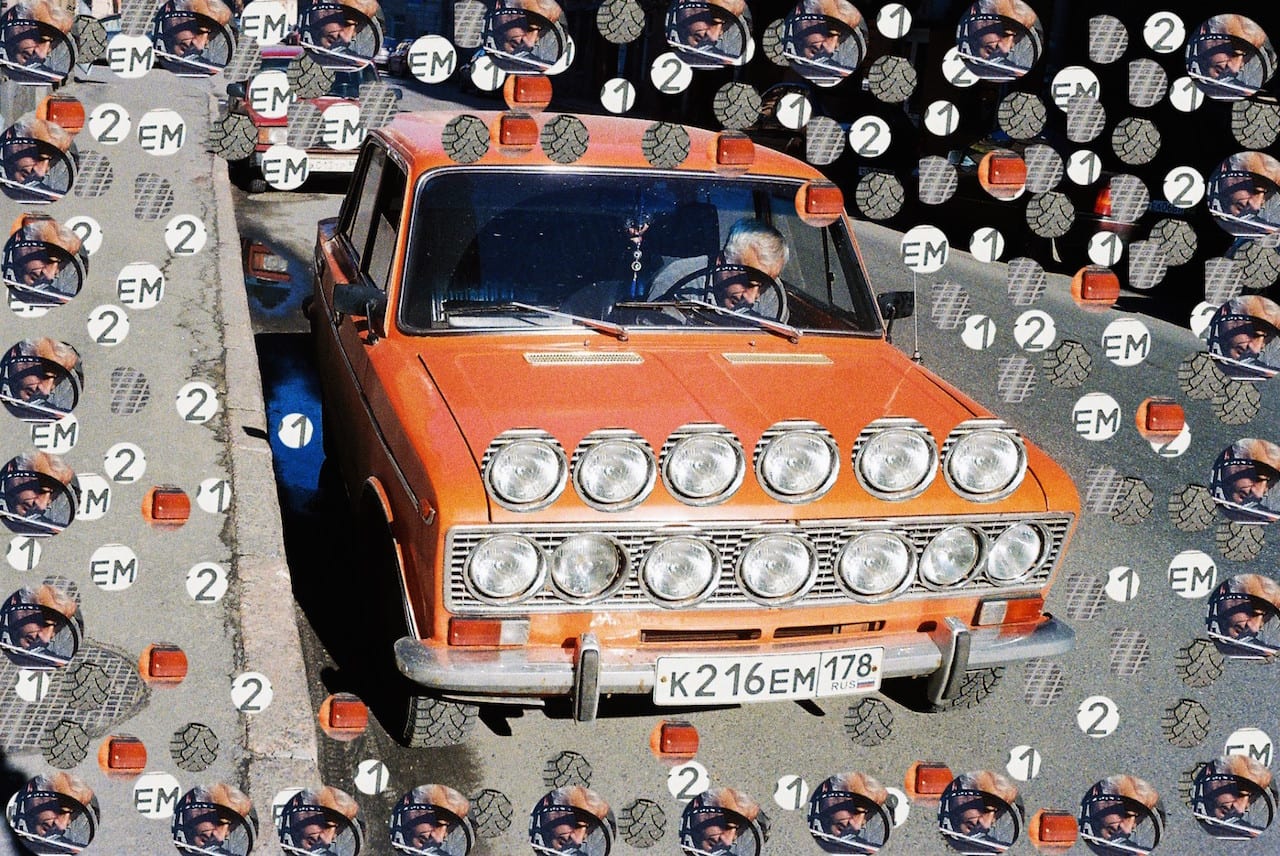

Born in 1982, Alexander Bondar grew up on the outskirts of Moscow and studied photography in the Faculty of Press Photographers at the St Petersburg House of Journalists. From 2010-2013 he took part in several workshops organised by FotoDepartment and ROSFOTO in St Petersburg, and in 2013 he started studying Photography and Time-Based Media at Jan Evangelista Purkyne University, Usti and Labem, in the Czech Republic. Bondar has shot four major photographic series, Unfit (St Petersburg, 2010-13), Pavlov’s Dog (St Petersburg, 2008-2015), No Dream To Dream (Czech Republic, 2013-2017), and Cat’s Eye (Warsaw, 2015-2016), plus another project called So Cliché (2009-2013), which uses deliberately heavy-handed retouching. He recently published Cat’s Eye and So Cliché with Zoopark Publishing Collective, a project which he set up with Tatyana Palyga in 2016. Bondar and Palyga have also published two editions of a magazine called Zoopark together, and have presented their work in Paris at Polycopies in 2016 and 2017. Bondar is represented by the FotoDepartment Gallery.

“These pictures were originally intended as a sort of ‘Fuck you’ to the Bush administration,”…

“I hate myself because I am a murderer… You can’t save me… We are a faceless, forgotten part of society…” These are just some of the intimate, often devastating thoughts of the inmates at HMP Grendon, a category B men’s facility in Buckinghamshire and Europe’s only “wholly therapeutic” prison. Their words accompany My Shadow’s Reflection, a series informed by Edmund Clark’s artist-in-residence at Grendon, which forms part of his larger body of work, In Place of Hate, on show at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham from 06 December.

It’s a commendable milestone by anyone’s standards – for 70 years, Magnum Photos has been at the forefront of documentary photography, photojournalism and visual storytelling, its members reporting on conflicts, crises and changes for humanity the world over. To celebrate Magnum’s long and rich history, the agency has devised Magnum Retold, a huge group project in which current members revisit stories by their predecessors. Photographers were invited to respond to an archival story that had influenced or inspired their practice in some way – a story that meant something to them personally, or a topical subject they wished to revisit. “There is a repository of amazing work, which is the 70-year-old legacy of these incredible photographers,” explains Magnum’s content director, Francesca Sears.

When New York-based photographer Marc Ohrem-Leclef first travelled to India eight years ago he was struck by the “small, shared moments of intimacy” that he saw men displaying towards one another in public – admiring the openness with which they made what he assumed were public displays of romantic love. “As a gay man, I was quite excited by what I thought was romantic freedom,” he says. “Men would be holding hands or leaning against each other in public. There was a connectivity that I thought was really beautiful.” He quickly learnt that things were not as he had first thought, that the men he saw were not necessarily romantically involved at all and were often just expressing friendship.

“The point is not to work out what it is, but to show how weird and wonderful the world can look from above”

Documentary images of North Korea have trickled steadily into the media landscape since the late 1990s. Since those granted access to the region are afforded little freedom to be creative, their main depictions are usually of totalitarian dictatorship, state-sanctioned ideologies, normalised militarism, and colossal architecture, all of which have become over-familiar in images of the country. This documentary déjà vu is what prompted Eddo Hartmann to pursue a multimedia project about North Korea, to act as a record for what many of us cannot see. The photographer visited Pyongyang, the country’s capital, four times between 2014 and 2017, creating thousands of large and medium format digital images of the city’s architecture and citizens. “I kept seeing images in this World Press Photo kind of style,” he explains. “I knew that if I were to go there, it would not be the way that I would take pictures, because it wouldn’t be interesting.”

For Susannah Ray to get into the centre of New York city, she must first travel over a series of bridges and waterways. Whether driving across Jamaica Bay or taking the subway from her home in Rockaway Beach, Queens to Brooklyn or Manhattan, she repeatedly finds herself captivated by the sights she encounters – the sky changing colour above the water; the birdwatchers on the shores; men fishing near a scrap metal yard, up to their waists in waders. She sees groups of people performing religious rituals, gatherings and prayers on the banks of the river. She sees more simply being. Ray’s image of New York is utterly coloured by its relationship with the water. So when she decided to create a portrait on the city, she decided to use those urban waterways to weave it all together. “The water serves so many different purposes for so many different people,” she says. “It acted as a focal point. The communal draw symbolises that idea of coexistence.”