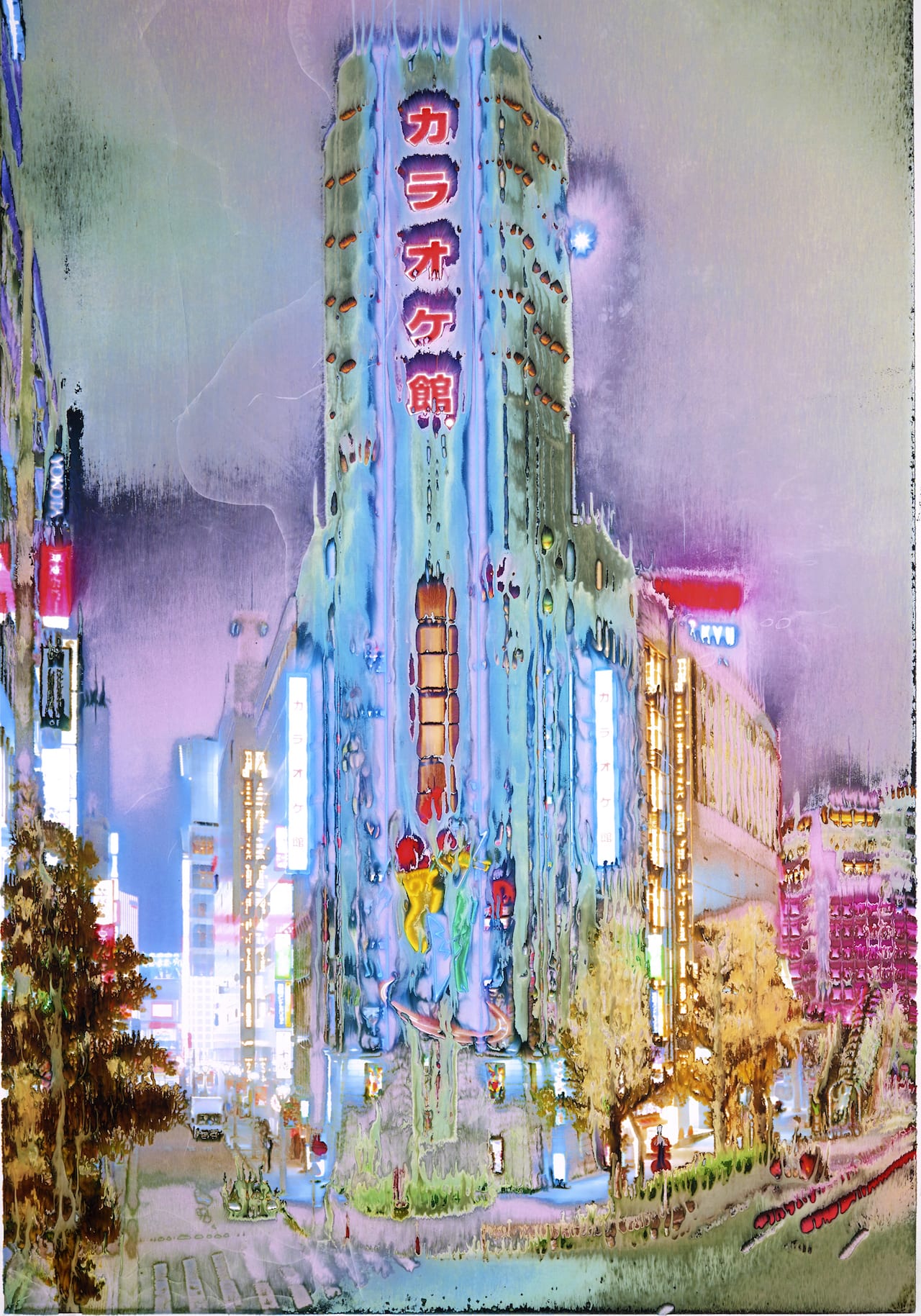

“I love how the city is in perpetual metamorphosis. It’s always moving and glowing,” says Jean-Vincent Simonet, who visited Tokyo, Japan for the first time in 2016, and quickly decided he would shoot at night. “Giving a liquid feeling to the photographs made sense to me. It reinforced the psychedelic experience of being in the city”.

People in Japan describe Tokyo as a “living entity” – not just because of the earthquakes and typhoons that regularly stir the capital, but because it is a city in constant flux. At all hours of the day and night, streams of people and cars rush down its huge neon streets, which sprawl out like tributaries into pedestrianised roads, stacked 10 stories high with shops, restaurants and karaoke bars. Vibrant city centres seem to emerge right off the back of darker inner-city suburban streets, which are all connected by colossal highways, and an elaborate train network that dwarfs most other capital cities’.