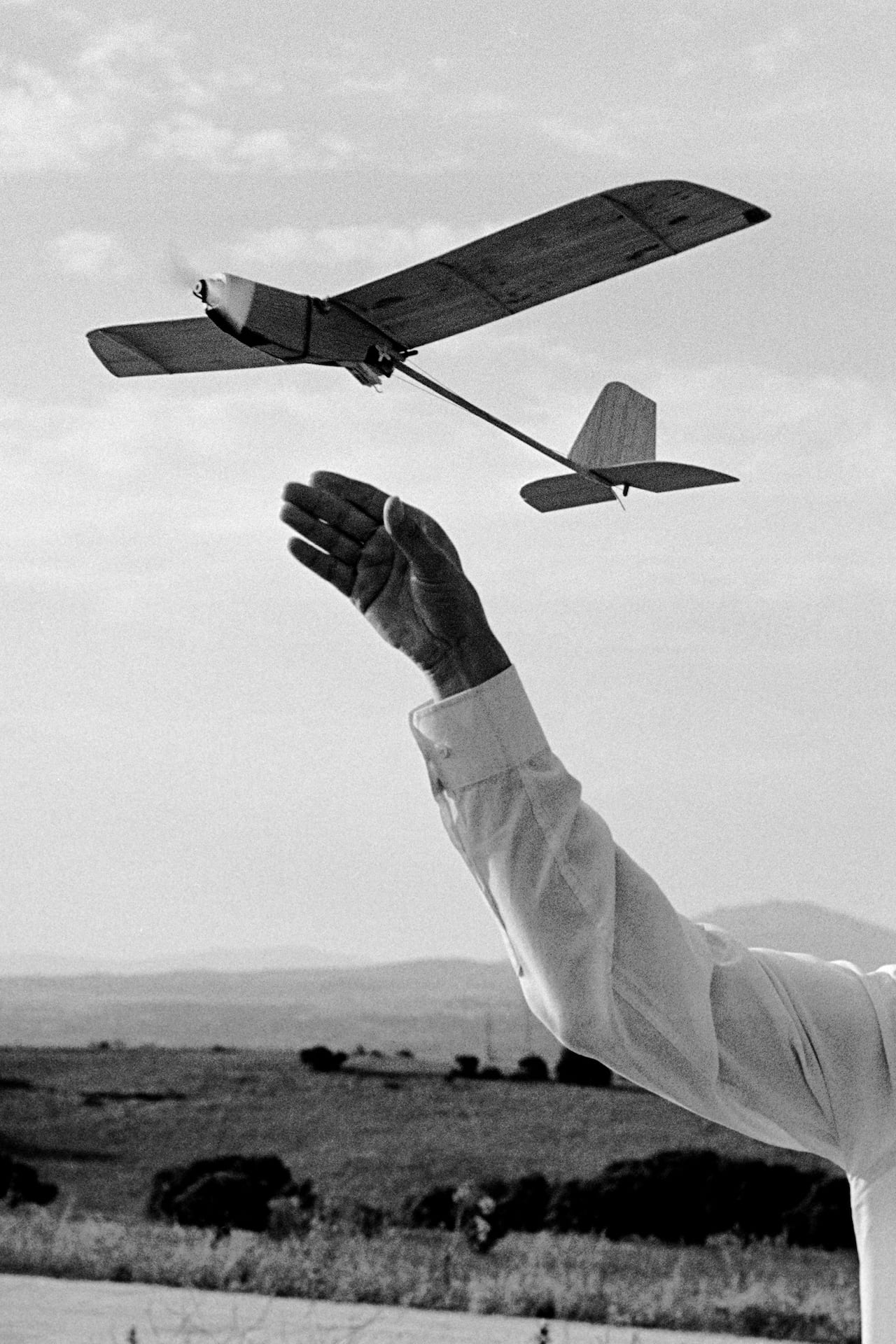

“It was a moment where I could step out of my ordinary and rather boring existence, and shape it into something different,” says Federico Clavarino, who’s photographs from his foundational years at Blank Paper in Madrid are now published as a book

“It was a moment where I could step out of my ordinary and rather boring existence, and shape it into something different,” says Federico Clavarino, who’s photographs from his foundational years at Blank Paper in Madrid are now published as a book

Rhiannon Adam spent four months immersed in the UK fracking debate. Her intimate portraits offer a glimpse into life on the frontline of the fracking resistance

Adrienne Surprenant’s portraits of patients at a wound hospital in western Cameroon seek to remove the stigma of chronic wounds

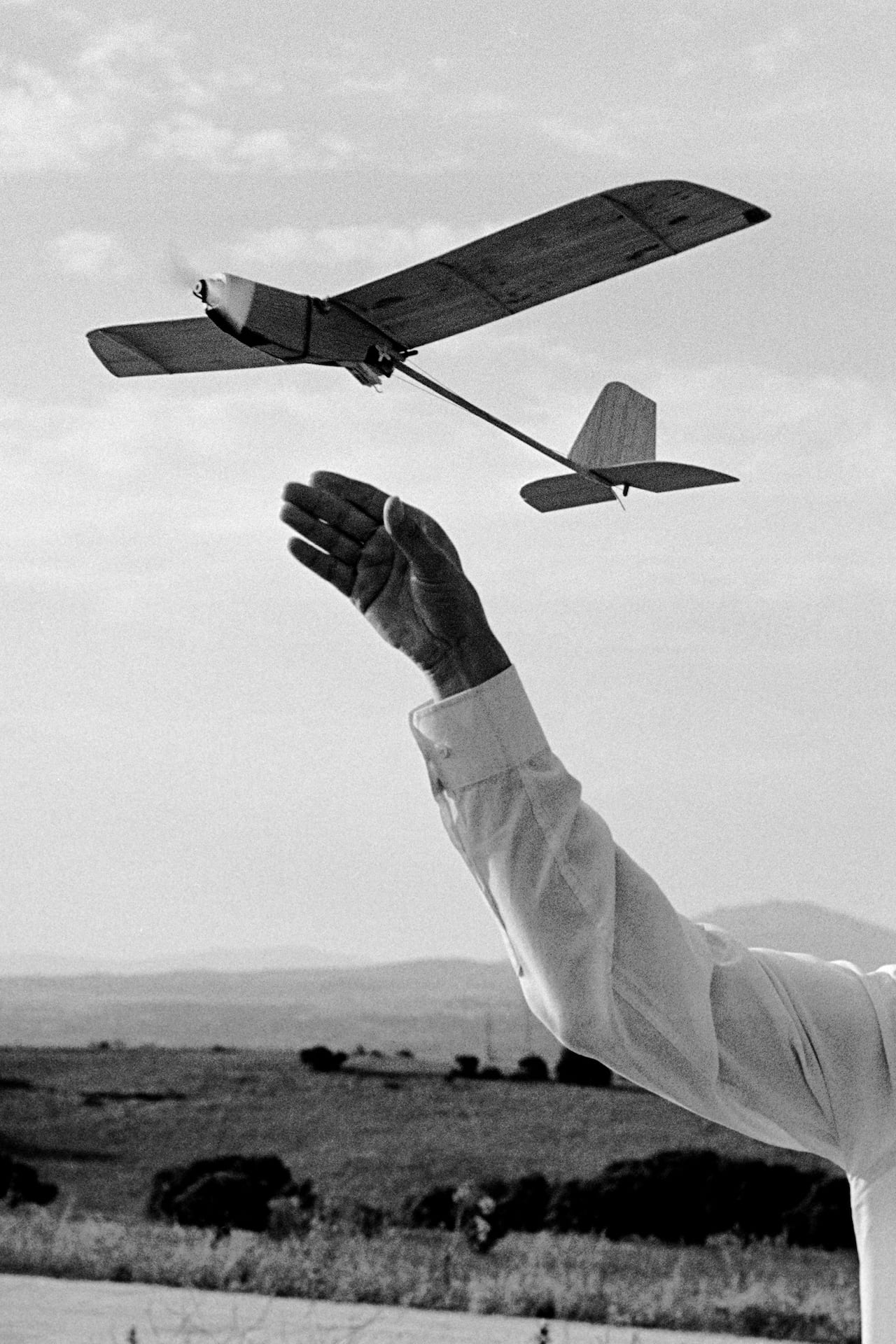

As a medical student specialising in youth and cognitive neuroscience, Claudio Majorana is not a typical documentary photographer. Having grown up with a mother in fine arts and a father in medicine, his attraction to the symbiosis between art and science was initiated at a young age, and his interest in photography – an artistic medium rooted in scientific process – came to him naturally. “Throughout my childhood, I spent tiSme painting in my mother’s atelier, or helping my father develop X-rays in his radiology darkroom. That’s where my interest in images began,” he reflects.

When Majorana was accepted into medical school at 19, he also began photographing voraciously. In the summer of 2011, he encountered a group of kids in the suburbs of Catania, his hometown in Sicily, and began documenting moments in their daily life, rooted in skateboarding culture and the general struggles and raucous habits that colour adolescent life. The result is his series, Head of the Lion.

A hairdresser, Vivienne Westwood and an 87-year-old activist: a photographic series that tells the stories of those for and against the controversial practice

Brant Slomovic leads a double life: he is both a photographer and accident and emergency doctor. A recent commission in California allowed him to reflect on his relationship with the former

In his latest book, Gap in the Hedge, Dan Wood looks at how a place affects the way you see the world around you, how it can open your mind to new vistas, create spaces for your imagination to run wild, and make an identity that is rooted in the landscape in ways that can be expanding or limiting.

The title refers to Bwlch-y-Clawdd, the mountain pass that joins Bridgend to the former mining communities of the Rhondda Valley. Built in 1928, the road was Wales’ biggest construction project at the time, intended to lift the Rhondda out of its over-reliance on coal mining. And it was some reliance. At its coal-mining peak, South Wales produced one third of global coal exports, with large numbers of migrants moving in to mine the coal, making it a surprisingly diverse community for a place that is still regarded as quintessentially Welsh.

“It’s a bit hard to find words for this – You don’t look Native to me won the PHmuseum Women Photographers Grant,” says Maria Sturm. “I feel exponentially happy and glad to be sharing the list with other women photographers whose work I admire.”

Sturm has won the prize in a strong year for the PHmuseum Women Photographers Grant, with the 31 shortlisted photographers including Magnum Photos’ Diana Markosian, Sputnik Photos’ Karolina Gembara, and Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize-winner Alice Mann. But her long-term project You don’t look Native to me, which shows young Native Americans in Pembroke, North Carolina impressed the judges with its sensitive approach to its subjects.

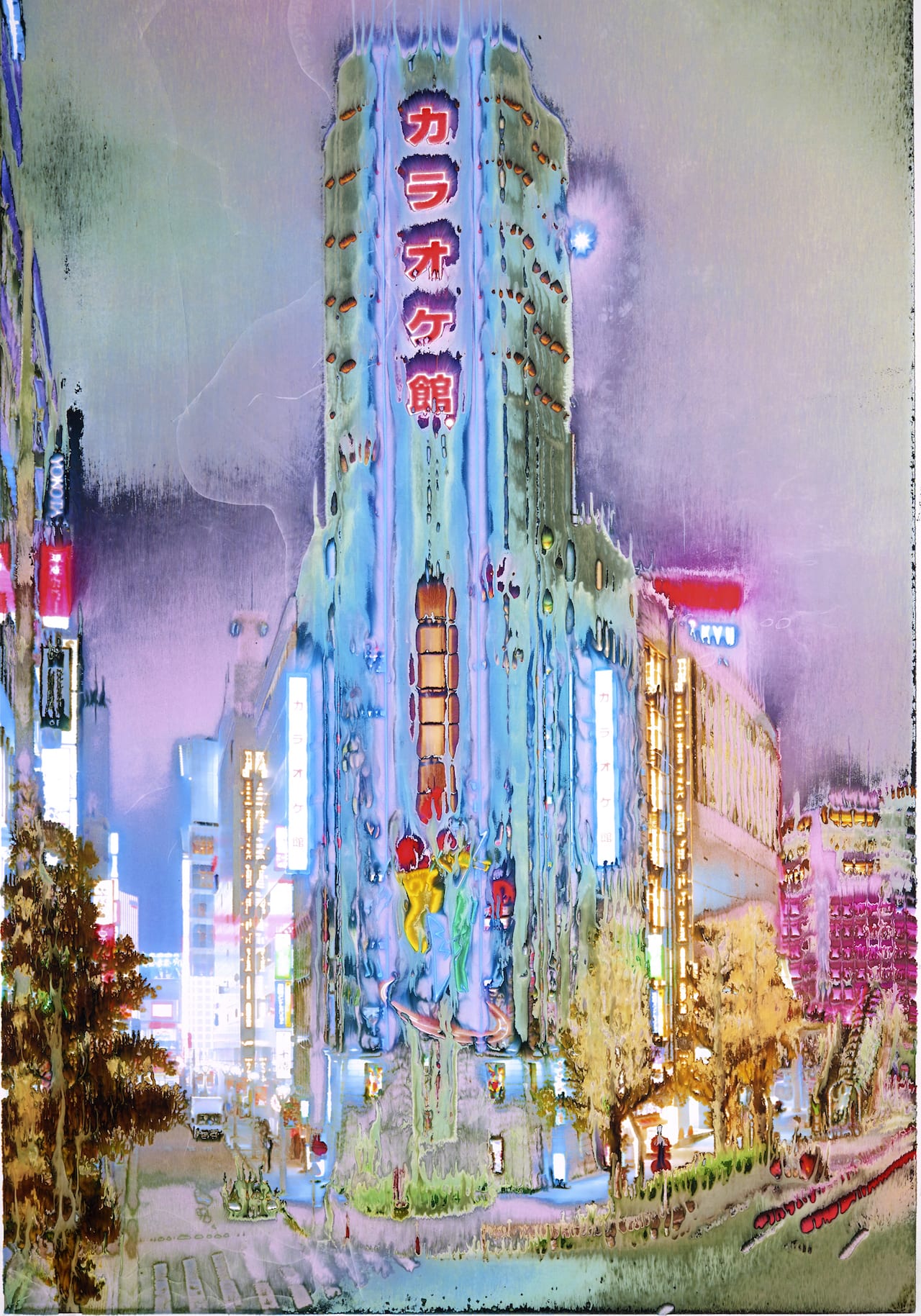

“I love how the city is in perpetual metamorphosis. It’s always moving and glowing,” says Jean-Vincent Simonet, who visited Tokyo, Japan for the first time in 2016, and quickly decided he would shoot at night. “Giving a liquid feeling to the photographs made sense to me. It reinforced the psychedelic experience of being in the city”.

People in Japan describe Tokyo as a “living entity” – not just because of the earthquakes and typhoons that regularly stir the capital, but because it is a city in constant flux. At all hours of the day and night, streams of people and cars rush down its huge neon streets, which sprawl out like tributaries into pedestrianised roads, stacked 10 stories high with shops, restaurants and karaoke bars. Vibrant city centres seem to emerge right off the back of darker inner-city suburban streets, which are all connected by colossal highways, and an elaborate train network that dwarfs most other capital cities’.