All images courtesy of the artist; The Modern Institute/ Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow; Anton Kern Gallery, New York; Galerie Neu, Berlin; and Gladstone Gallery, Brussels

The New York conceptualist has long turned the camera on itself to question visual cultures. A new show deepens her inquiry into the nature of spectatorship – both human and machine

If the feeling of being watched is an anxiety relying on setting and suspicion, the real thing at least brings with it the comfort of certainty. Confirmation of being observed offers the opportunity to react – to relish, reject or engage with the act of being watched; to create some kind of bond with the viewer. Anne Collier taps into these possibilities in her latest exhibition, Eye, creating a world of spectatorship using her artworks featuring eyes. Some are self-portraits, others fragments from adverts or vintage comic books. All say something about the nature of looking and being looked at – the power and potential of visibilities.

Collier has long made use of eyes in her found imagery and portraits, allowing her to question the photographic process but retain human connection. Her most incisive works probe the relationship between the two while gesturing towards, but never fully succumbing to, some of photography’s fundamental questions – what constitutes ‘the photographer’s eye’, or the punning inquiry into the nature of lenses, both human and machine. The Los Angeles-born artist’s work is wry and restrained, wielding slithers of visual material to interrogate photography and the cultures it partakes in – without needing to offer answers to the craft’s deeper crises.

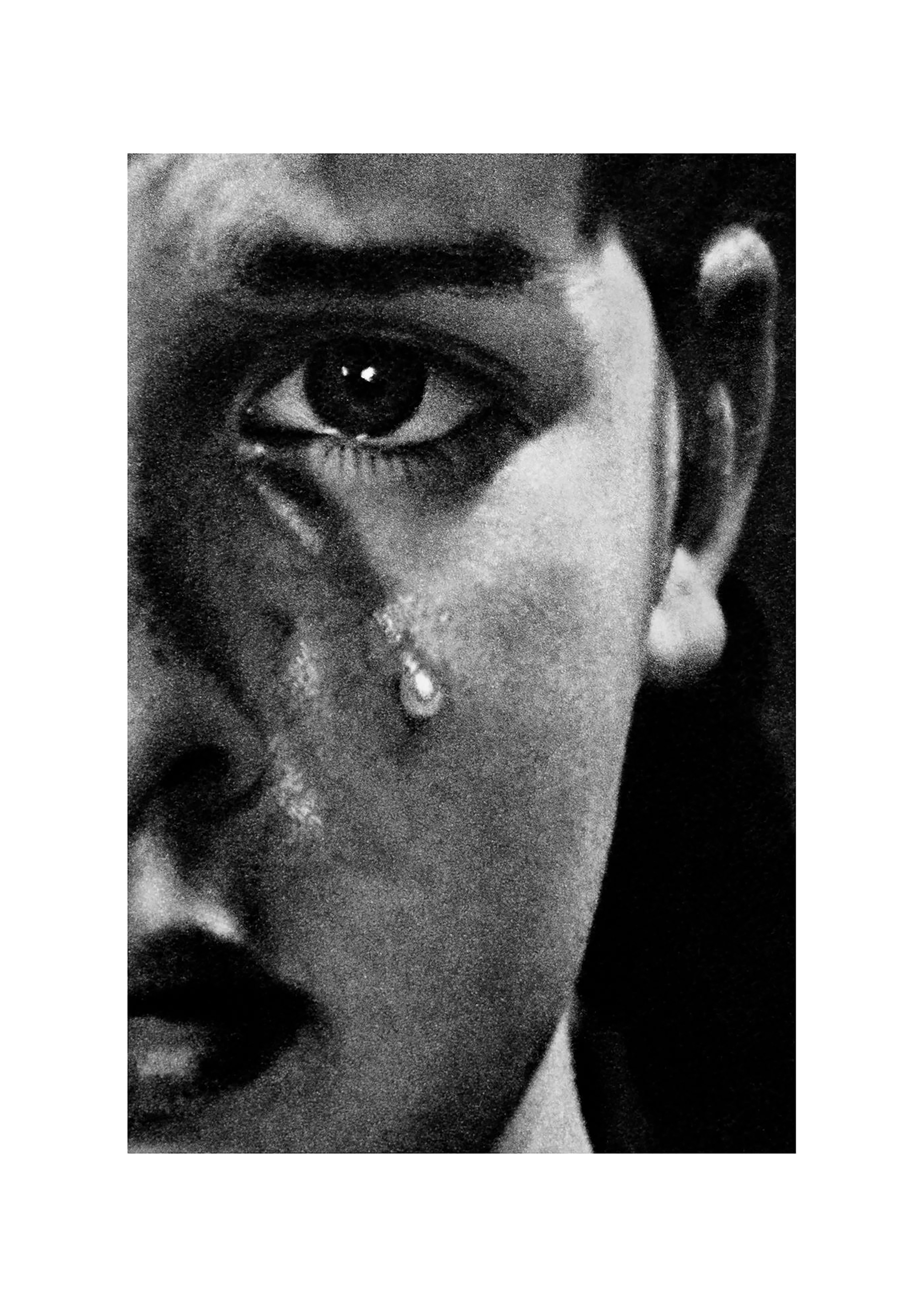

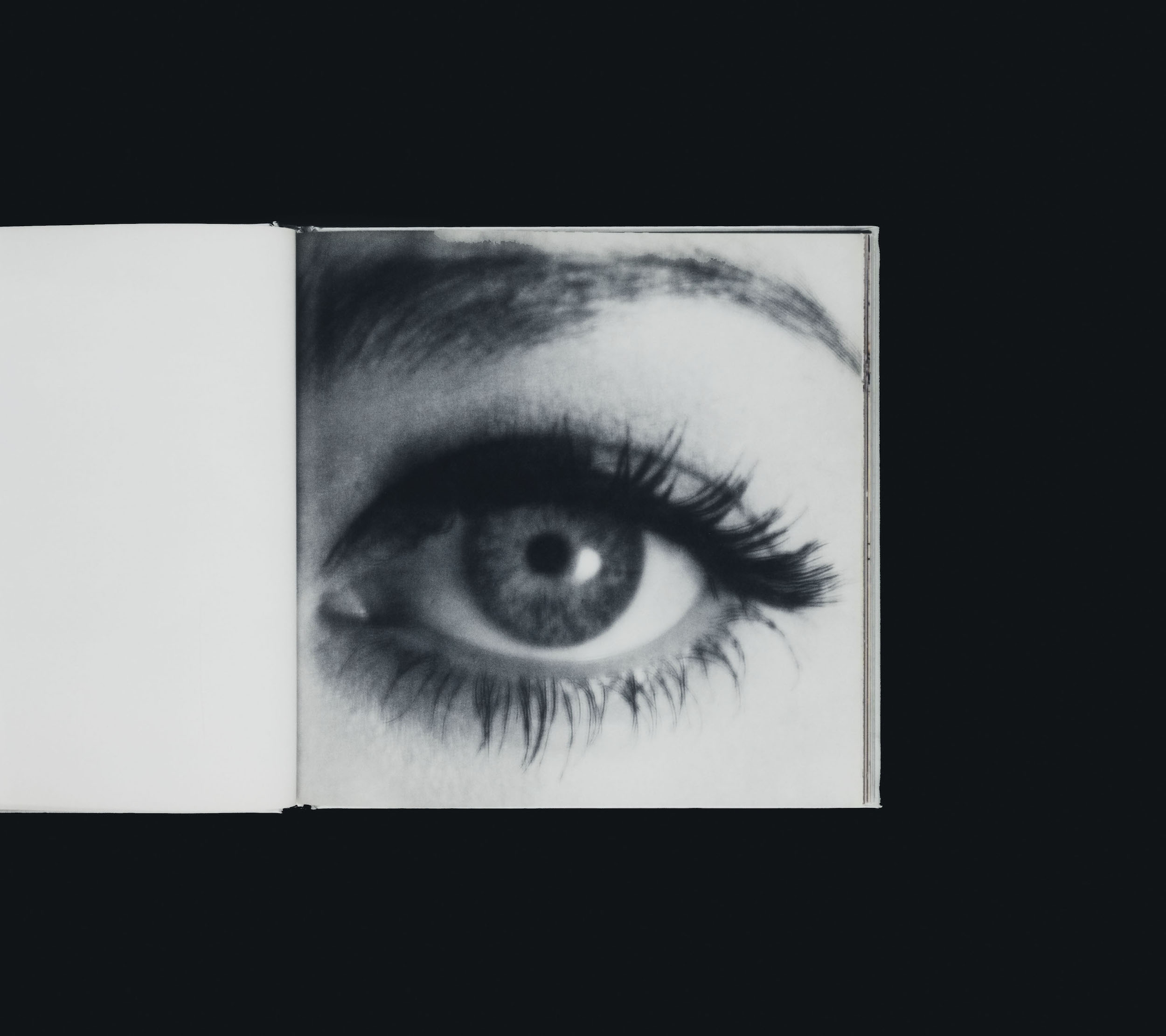

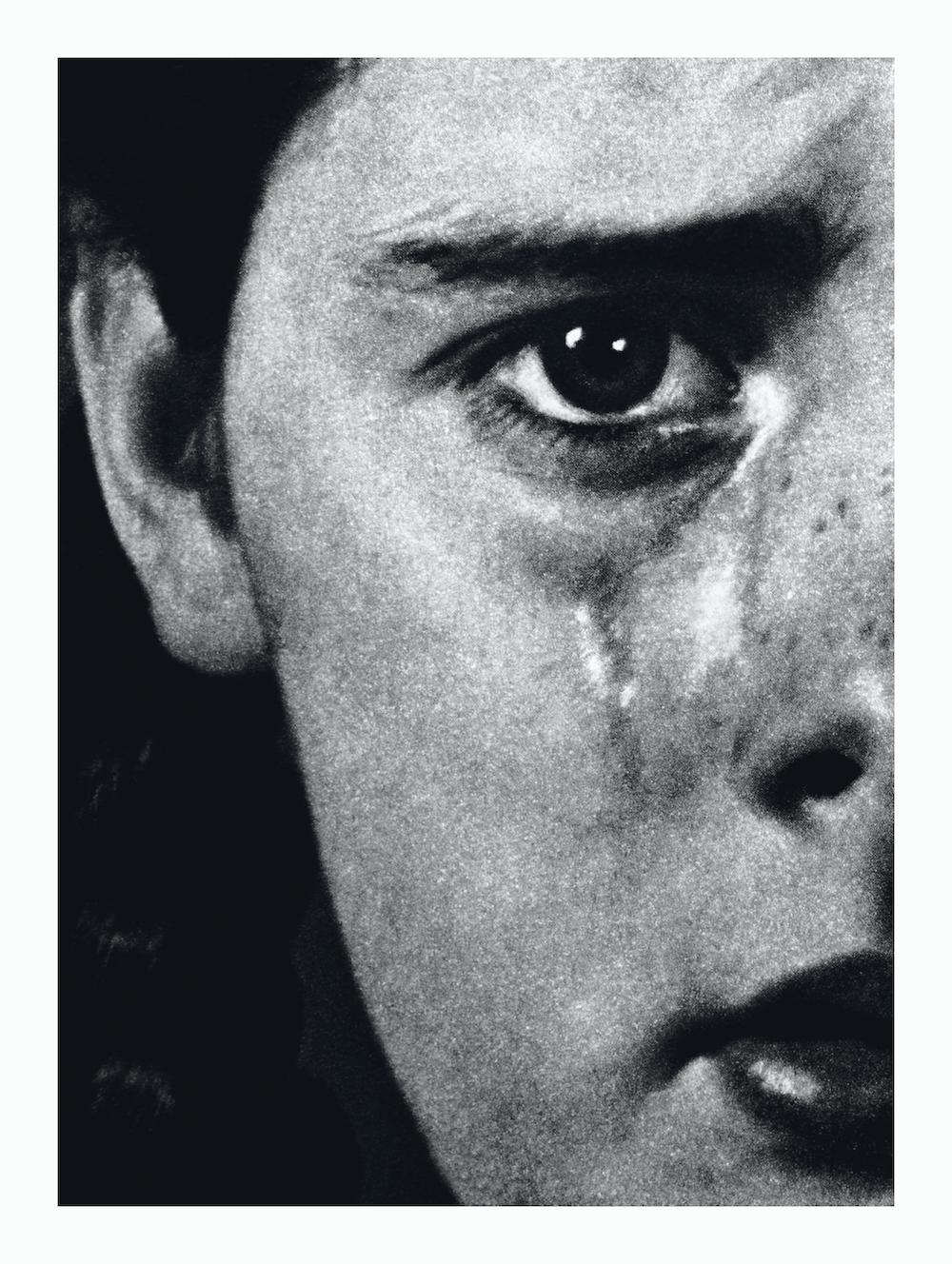

The show at Lismore Castle Arts in Ireland includes three of Collier’s self-portraits centred on the development and display of print photographs. Developing Tray #2 (Grey) and Cut feature her own eye as subject material in the darkroom, while Eye (Soft Contours) is an image of a photobook, Collier’s pupil enlarged and piercing. Eye #1 features the artist holding a small print of her own eye, her arm emerging from the base of the work to add an extra layer of self-reflexiveness.

Collier’s decision to use her own body in the pictures lifts them from conceptualism to something more affective. If, on the one hand, eyes are essential instruments of the photographic process – just one device among many in the artist’s toolbox – they are also portals of emotion and ageing. Although Collier detaches and isolates her eyes from the rest of her body in the pictures, their ‘looking’ back at the viewer is an invitation into a world of speculation. Suddenly we wonder what these eyes (and our own) have seen or missed. To be with these works – each made between 2009 and 2014 – is to witness and ponder time’s passing; to ruminate and recollect via the artist’s diaristic organ.

This combination of technicality and affection has defined Collier’s work for over two decades, holding it between concept and confession. Collier’s 2014 solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago included works that directly reference the artist’s late parents, an explicit call to reflect on loss. Michael Darling, who curated the show, remarked that Collier leads viewers “to this precipice of mourning and psychological frailty”, an artist deeply in touch with fear, anger, despair and guilt – emotions all present in her pictures of self-help cassette tapes from 2002, which were included in Chicago.

“To be with these works – each made between 2009 and 2014 – is to witness and ponder time’s passing; to ruminate and recollect via the artist’s diaristic organ”

Eye’s invitations are broader and more obscure. Instead of mining Collier’s own life for emotional prompts, the exhibition relies heavily on the eye as a variable symbol – capable of sparking deep introspection while also reflecting the state of Western visual culture, and particularly the role of gender. Psychological inquiry is widened, replaced with cultural critique and melancholic overtones. It is a similar formula to Women With Cameras (Anonymous), Collier’s 2017 project of 80 found pictures of women taking photographs. On the surface, the eye has replaced the camera as the recurring motif. In reality, Collier’s inquiry depends on the inextricability of the two.

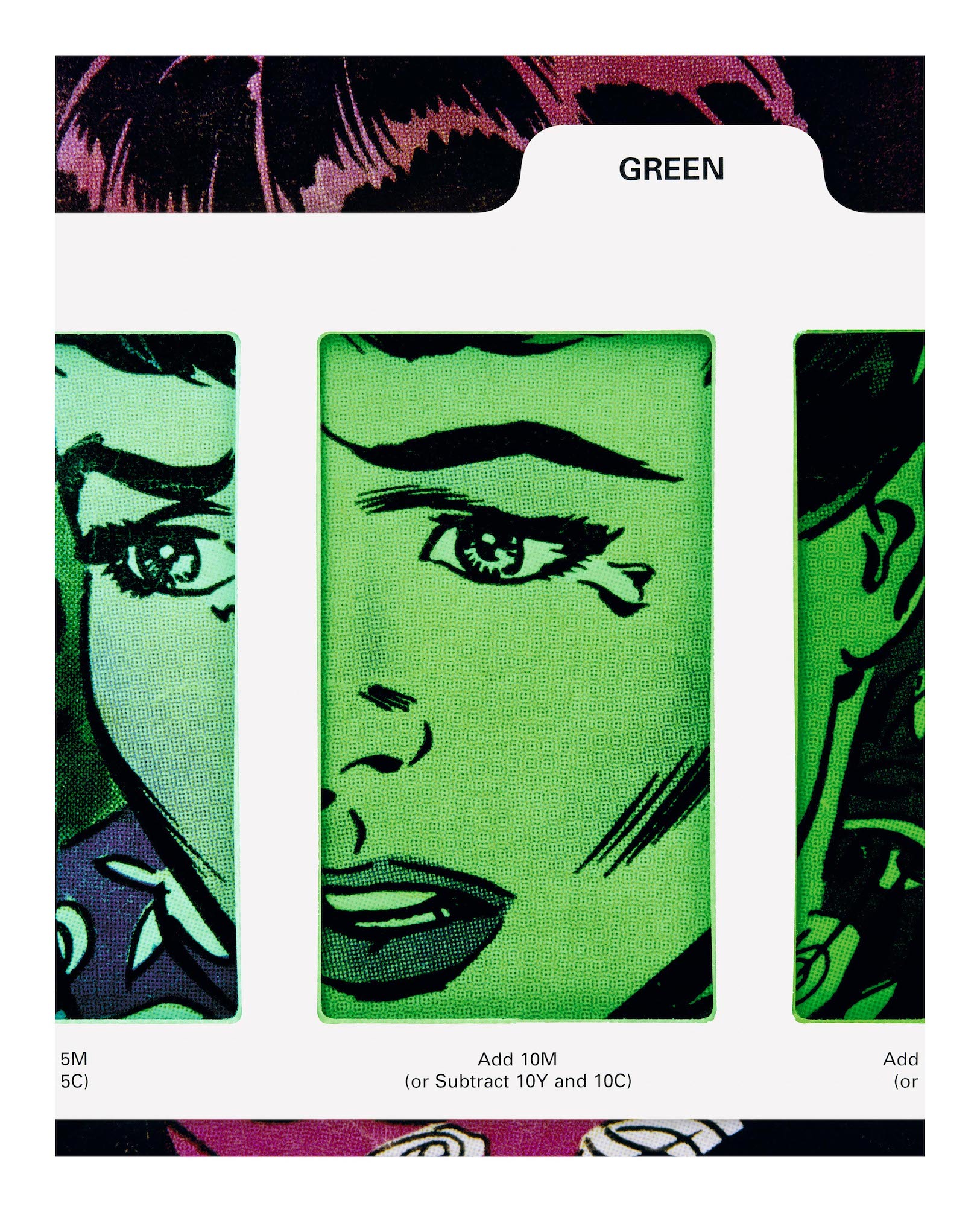

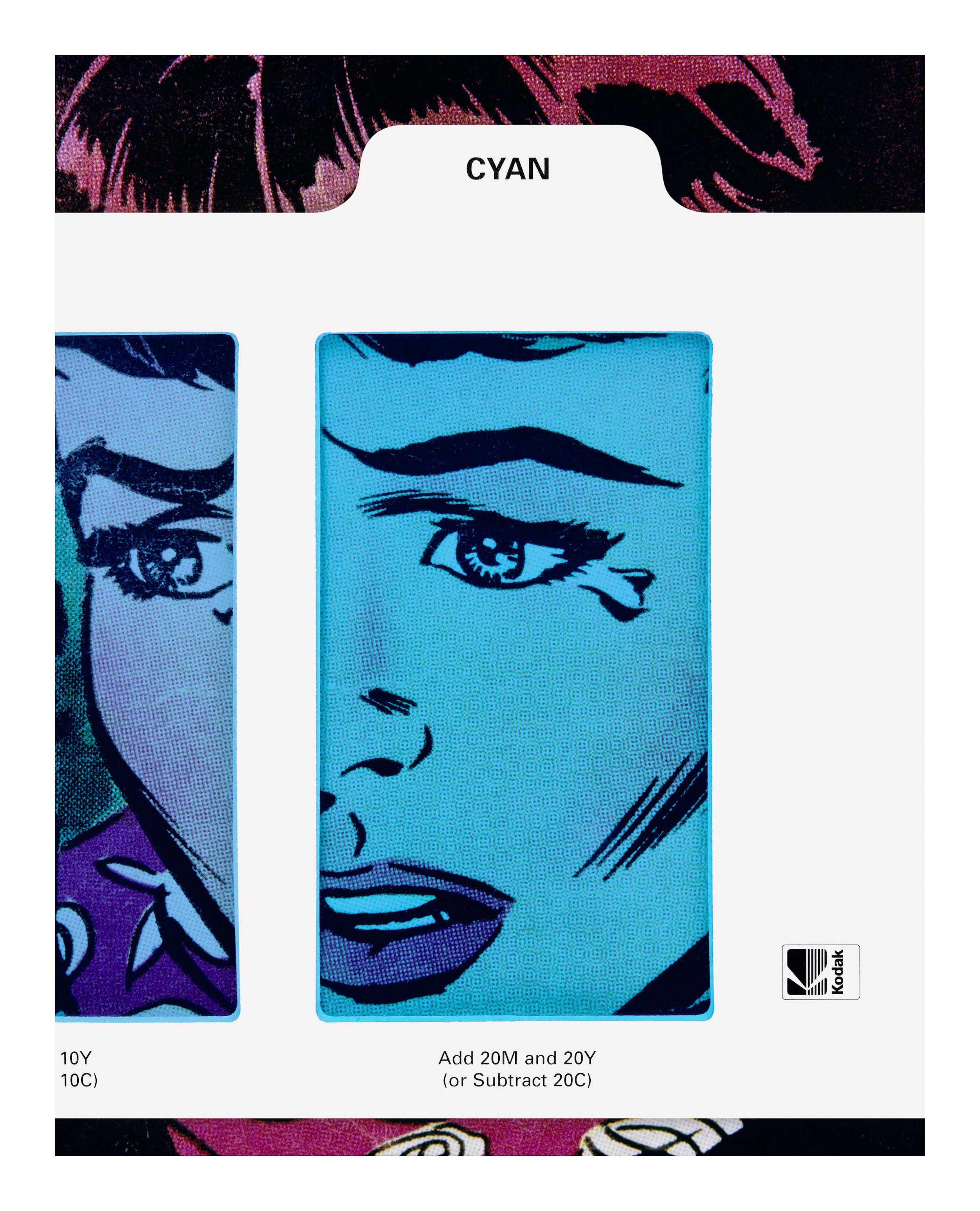

Collier’s 2021 Filter #4 series is the epitome of this shift, a close-up of a crying woman from a romance comic book framed by a Kodak Colour Print Viewing Filter. When displayed in series, the six variations create a sense of incremental but constricted change – a nod to the production skills crucial to developing photographs, but also the static, frustrated ways visual culture depicts women as emotionally vulnerable. Minor adjustments draw attention to that which refuses to evolve. Not quite, as the exhibition text suggests, a “liminal space between the photographic and the cinematic”, but a stuttering, iterative exploration of visual culture’s dogma – and a veiled call for image-makers to consider radical alternatives.

Collier started building up an archive from photo manuals, adverts, film stills, album sleeves and comics in 2006. She lets the images speak for themselves, rarely imposing a narrative beyond the technical processes invoked in the Filter works. Lifting the pictures from their original contexts brings them into new, uncertain spheres of meaning. Products are stripped from adverts, pages cut from manuals – allowing signification to meander in the space between image and viewer. Woman Crying #20 and Woman Crying #21 appear to show despair in harrowing black-and-white. In reality, the shots are lifted from a mayonnaise advert. The Photographer’s Eye is completely unaltered, its objectification of a female subject requiring no explanation. Here is a deeply sexist visual culture, thriving on spectatorship, with photography as one of its most potent and implicated tools.

The artist has previously described her work as “deflected self-portraiture”, where her aim was to “find objects or artefacts that could somehow operate as ‘surrogates’ for aspects of my own identity and personality”. Eye signals a shift from this method, where both the eye and camera are held in deliberate ambiguity. Both are organs, tools and invitations at once. In this sphere of uncertainty, fragments of visual media are brought into Collier’s new schema of gendered and photographic self-critique. The result is a show of deep interconnection and (in)sight.