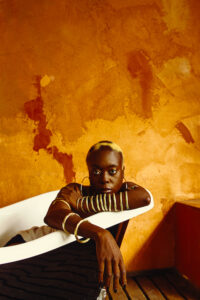

© Jialin Yan.

Genesis Báez, Jialin Yan and Anne Vetter use the camera to reflect on the self, drawing on self-portraiture but also documenting the people and places that directly shape their unique identity

The documentation of self has been foundational to photography. Evolving out of studios in the 19th century, early photographers including Louis Daguerre (1787–1851) took advantage of self-portraits to explore the camera’s potential. The self-portrait has since become a staple of photography, led by artists such as Samuel Fosso [pages 82–98], Gillian Wearing and Zanele Muholi, who have turned the camera on themselves as an act of empowerment, performance or activism.

Portraits, in the classic sense of the word, are not the only way to represent the self through photography. Genesis Báez, Jialin Yan and Anne Vetter use the camera to explore their sense of self by making selfportraits, but also by documenting the people and places that shape who they are. This includes ruminating on diasporic identity, as Báez does in La Luz También Viaja (Light Also Travels).

The book brings together work about her sense of belonging through depicting matriarchal bonds alongside places that remind her of Puerto Rico and the US. Yan records quiet moments in her project Family Fragment to rebuild closeness with her parents, work through past traumas and become at peace with herself. Meanwhile, Vetter photographs themself alongside their family and partner in Love is not the last room to understand their “own gender in my own body in relationship to the people who I love most”. Vetter sees the project as “tides or waves” as it ebbs and flows, capturing different moments, spaces and places in time.

A sense of movement recurs throughout all three of these photographers’ work. By looking at their images we might also find moments to reflect on our versions of self, the places and spaces we call home, and the people we surround ourselves with, the big and little things that make us, us. Below, we take a closer look at the artists work, which expands on what it means to portray the self through photography.

Genesis Báez

Born in Massachusetts and raised in the US and Puerto Rico, Genesis Báez reflects on her diasporic identity by photographing the women in her family, as well as people who remind her of them. Much of her work, such as the project A Bridge of Mirrors, is made in both countries, although particular places are not identified. “It’s not geographically specific, but more about that lack of geographic space that is diaspora,” she explains. Báez sometimes appears in fragments: a hand reaching to hold a rope or lifting a water container with her mother, bare feet, the sunlight bouncing off the water creating curves on the floor. In another, Báez’s mother plaits her hair, their silhouettes multiplied, caught mid-plait [below].

Báez’s images of people often start with “a premeditated gesture that feels symbolic in some way”. In one, four students from a Latinx sorority stand in a circle, hands resting on each other in a protective gesture of care [left]. In another, a girl whispers to her friend as she makes rings around the edge of a glass of water. “They reminded me of my family, we built a bond, and so we started making pictures together,” Báez explains. Although she is creating images that relate to her family and identity, “not all of the people are related by blood, but one of the fundamental themes in my work is about visualising these invisible threads that connect people, through time and distance because diaspora is so much about dispersion”. This movement and fragmentation recurs throughout the project. Báez comments that although “the images may feel a little fragmented, I see it as being somewhat akin to diasporic life as you’re trying to make sense of your world, your language and yourself, through fragments.”

Jialin Yan

Quiet moments and gestures can be found in Jialin Yan’s project, Family Fragment. Yan’s mother draws back the curtains in one image, her hand covering her reflection in another, or tenderly holding the artist’s hand as she reaches over. The work was made in and around her hometown of Fuzhou, China, where she returned in 2016 after spending time in the UK. The images work through past traumas and unpack how the place that she grew up influences and contributes to the version of self that she is today. Family Fragment is about “how I deal with myself. This place where I grew up, the people around me, they shape me in a lot of ways. And if I can’t face them, that means I can’t face the past part of myself.”

Yan also uses her camera to reconnect to her family. Growing up “I wasn’t close to them because I was the only kid due to the one-child policy [in China] in my generation,” she explains. “For a very long time I was far away from my family, both mentally and physically. I have always been rebellious and my parents are traditional Chinese parents who focus on collective values… whenever I was with them, I always felt too self-assertive and we often had arguments.”

After moving into her grandmother’s home during the pandemic, Yan turned the camera on herself and her family. There’s a quietness that is felt throughout Family Fragment: a singular car parked outside an apartment block, a dining room table surrounded by four empty chairs. Yan’s mother and grandmother appear throughout the project, often in moments of reflection. In one image, her grandmother sits cross-legged on the bed, looking down in contemplation, while in another, her mother is captured resting her head on her hand as she looks over water. The camera records these moments, but also acts as a catalyst to start important conversations. “Once I started talking about this project with my mother, she started to unfold herself in front of me, sharing her vulnerable side – talking about her perspective on death and how she lost important people in her life. I feel like at that time, she was not only my mother, she was a daughter, she was a woman. She is everyone, she is the future version of me.”

Anne Vetter

In Love is not the last room, Anne Vetter turns the camera on themself and those around them to look at the fluidity of identity, alongside the intimacy and playfulness of their family and loved ones. The project began with a focus on leisure, space and time, but as Vetter continued to shoot, “I realised that the work was so much about queerness in my family,” they explain. “What’s a queer relationship with a parent or with a sibling?” In one image, we see Vetter’s father and brother exercising in the garden. Caught in motion, their bodies are tense, faces looking down in concentration. “I became really interested in how my dad was forming his sense of masculinity, his sense of gender, his sense of ‘straightness’. And how my brothers and mum do the same.”

Vetter’s brother Douglas plays a key part in the project. He is portrayed alone, with their father or with friends. Since 2020, Vetter has been making “self-portraits, with him as me”. In Self Portrait, Self Portrait as my Brother Douglas [opposite, top], an image of the artist and their brother are paired together. They are both wearing a Star of David necklace, posing the same with tilted heads holding our gaze. Vetter is wearing a white T-shirt, while Douglas is topless. Vetter’s hair is long, falling down their back; Douglas’ is short and wavy. “I was pretty certain that he was representing this part of me that I would never see because I’m gender fluid. But the more that I’ve made the work, the more [I see] Douglas as me, the more I become ambivalent [to it]: what does this actually mean about what I want?” Vetter uses the camera to understand and reflect on self-representation and aspiration, alongside those around them. Looking back on these images has encouraged them to question “how I actually want to see myself”.