The British artist sheds a mesmerising light on the degradation and contamination wrought by plastic particles in today’s natural environment

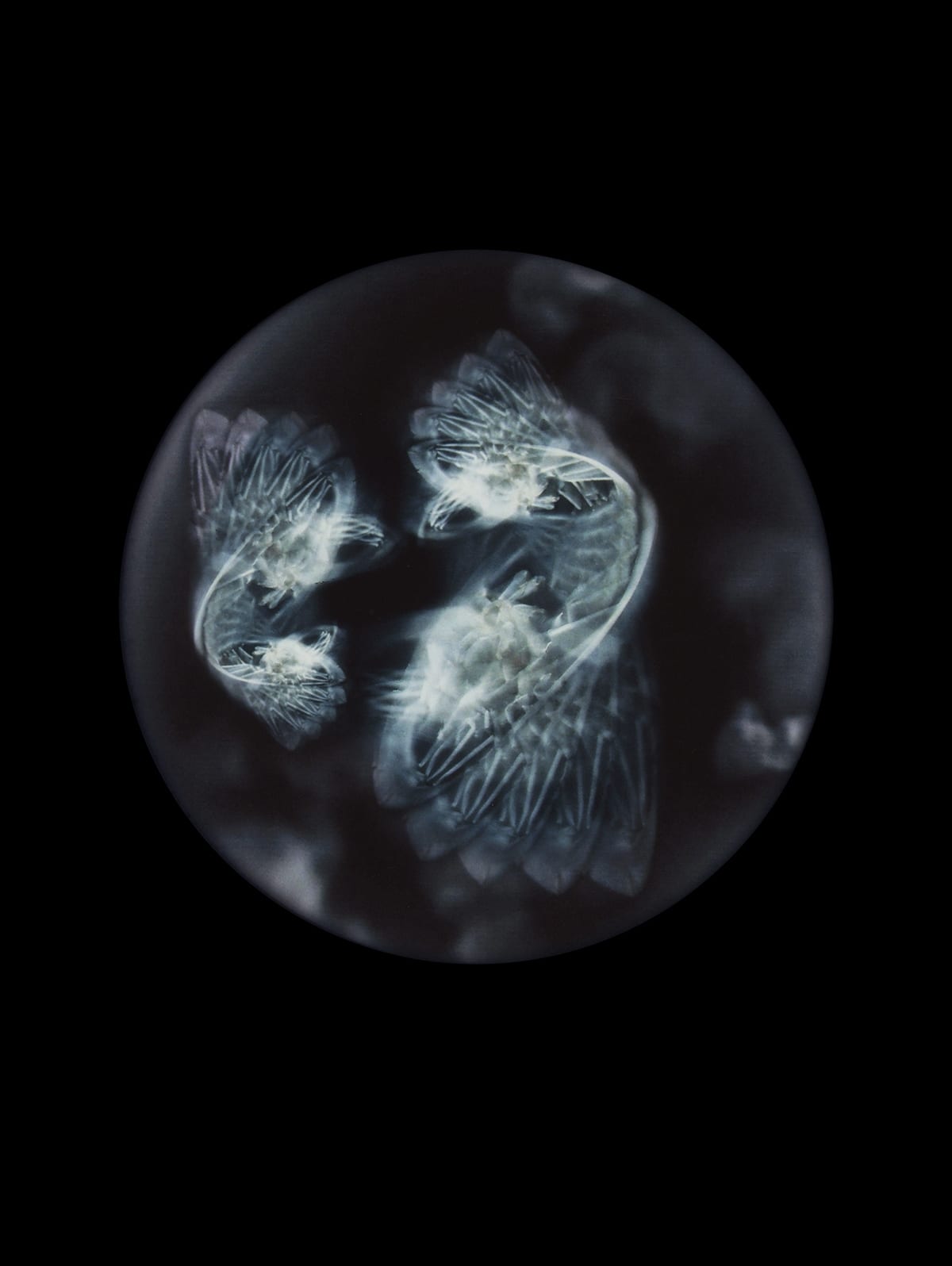

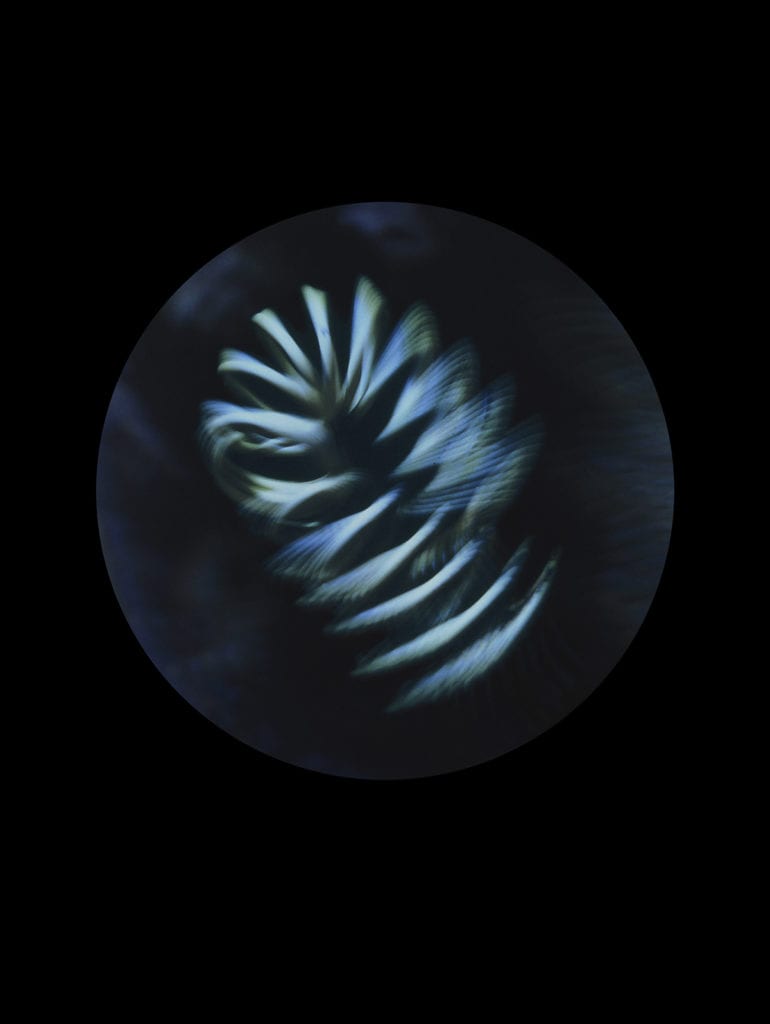

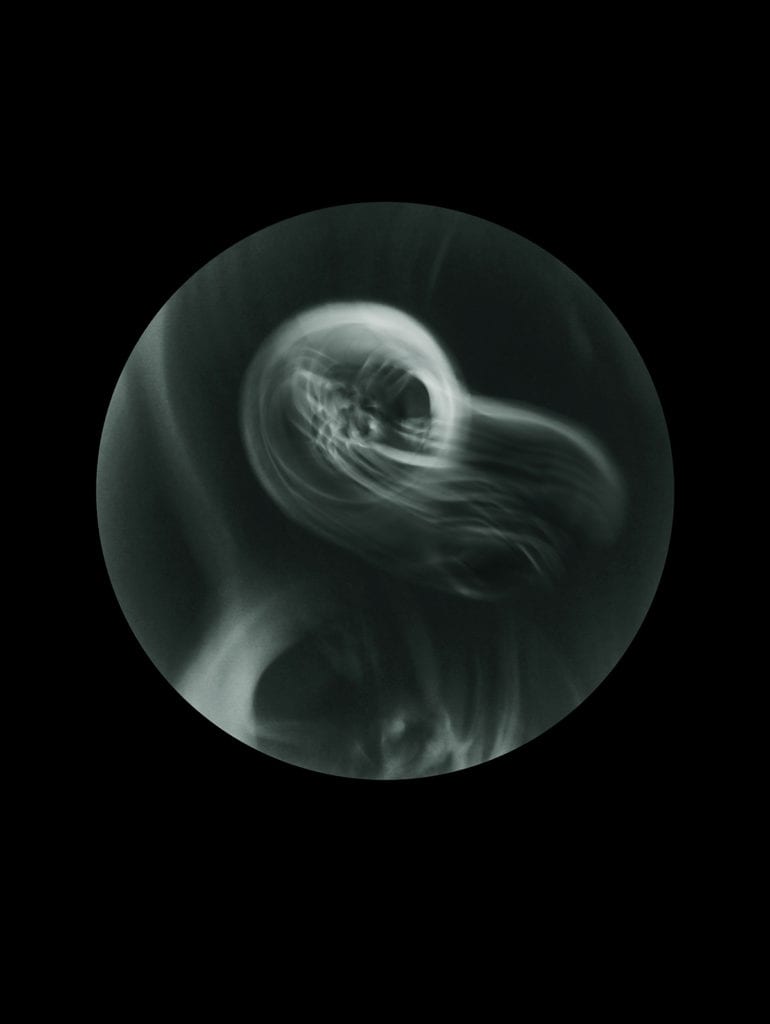

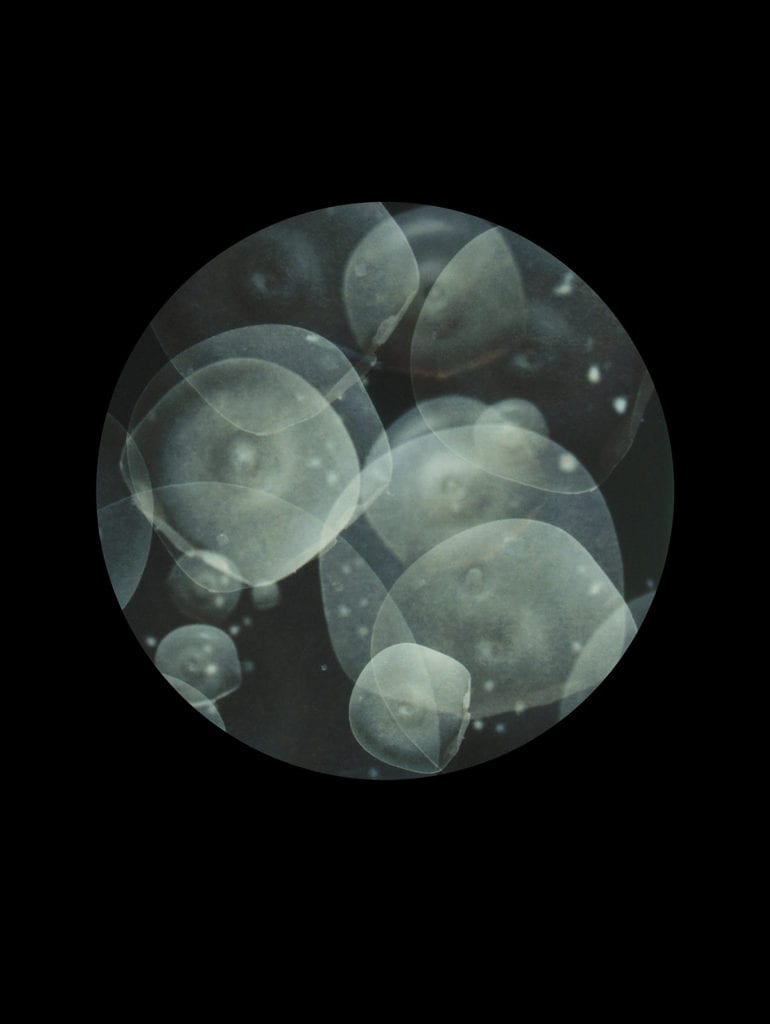

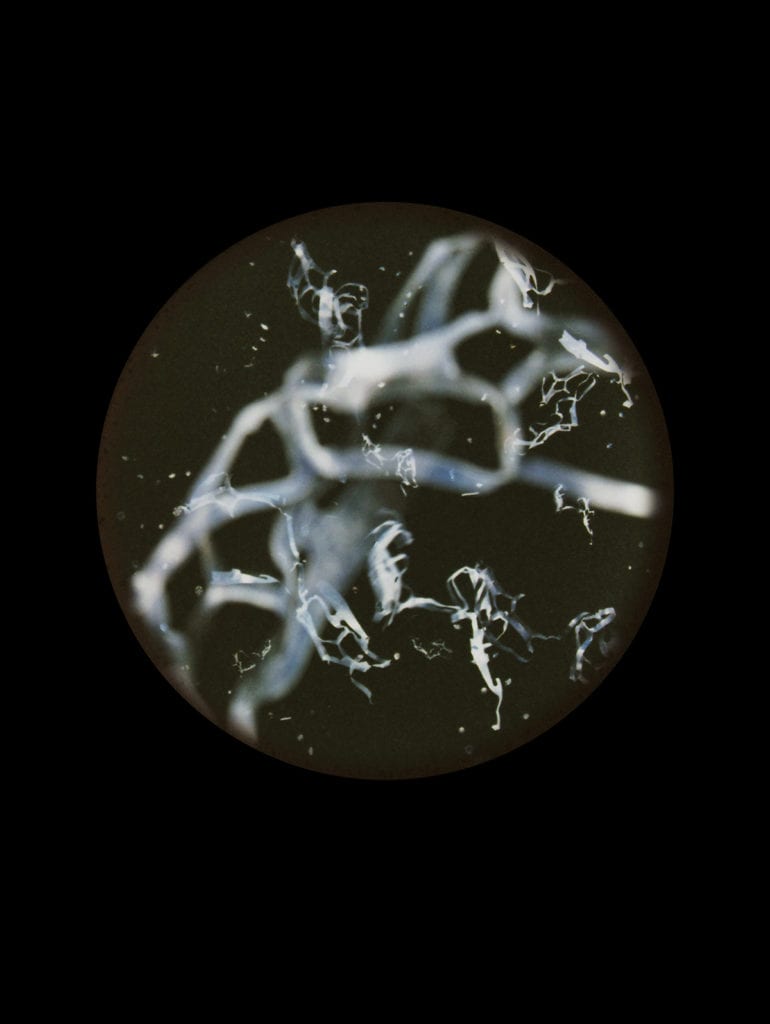

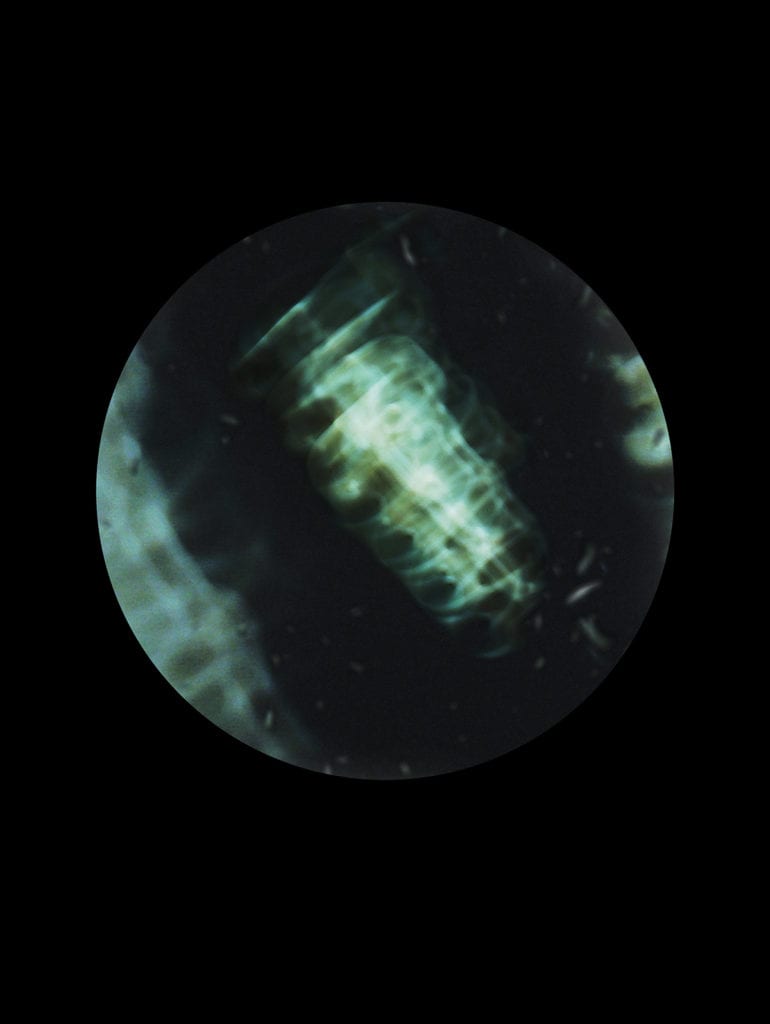

Milky, indiscernible forms float amongst enveloping blackness in Mandy Barker’s Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals. The 26 “specimens” — presented as microscopic samples, akin to the aesthetic of a 19th century science album — are at once eerie and ethereal to observe; upon first glance, they whisper of wonder, intrigue and discovery. But a closer look reveals a more sobering reality: Beyond Drifting is, in actuality, a survey of washed up plastic collected by the British artist on the shores of Ireland.

Today, no part of our planet is free of plastic waste. Enough plastic has been manufactured since the end of the Second World War to coat the entire earth in plastic wrap: around 5 billion tons; close to the weight of the entire human population at this moment. In Barker’s Beyond Drifting, the likes of doll arms, shoe soles and tricycle wheels recovered from Cork’s beaches are obscured through the use of long exposures, faulty cameras and expired film, alluding to the millions of tons of plastic debris that now permeate our oceans — and crucially, its insidious relationship with plankton.

“Without these remarkable creatures the oceans would be a barren wilderness. There would be no fish in the sea, we would have no reserves of oil or gas and the earth’s climate would be very different.”

“Plastic pollution in the ocean is set to treble by 2025,” says Barker, “and there’s going to be more plastic in the sea than fish.” One of the lesser-known ramifications of this crisis, as revealed by scientific research in recent years, is that plankton ingest micro-plastic particles, mistaking them for food. Plankton are plant-like cells, many smaller than the diameter of a human hair; they drift in the sea, underpinning the marine food chain, providing the world with oxygen and playing an essential role in the global carbon cycle. “Without these remarkable creatures the oceans would be a barren wilderness,” the artist says. “There would be no fish in the sea, we would have no reserves of oil or gas and the earth’s climate would be very different.”

Since plankton rest at the base of the food chain, they are themselves a crucial source of food for many larger creatures. “The potential impact of plankton’s plastic ingestion and the resulting effect on marine life and, ultimately, man itself, is of vital concern,” says Barker. “Microplastics within plankton could end up on our plates, with the fish that we eat.”

With this in mind, Beyond Drifting — published as an acclaimed photobook in 2017, and nominated for the Prix Pictet in the same year — mimics Victorian naturalist John Vaughan Thompson’s early discoveries of plankton in Cobh, Cork Harbour, in the 1800s, 200 years before Barker wandered the same shores. Movements of her recovered plastic objects, recorded with a camera over several seconds, represent the movement of individual plankton in the water column, while the added elements of expired film and faulty cameras “highlight the ‘imperfection’ in both technique and subject matter.”

“The plankton samples in this series represent imperfection in terms of man-made microplastics being able to infiltrate a natural organism,” Barker writes in her photobook. “Microplastic particles are not normally visible to the human eye, and their contamination of the food chain reflects an unnatural threat to the biodiversity of our planet.”

The book includes subtle references to the original text and figures recorded in Thompson’s research memoirs of 1830 (titled ‘Zoological Researches and Illustrations; or Nondescript or Imperfectly Known Animals’), harking back to an age when plankton were free from microplastic corruption. Barker even employs nomenclature — the practice of devising new scientific names — in her captions, assigning each specimen a name that imitates early latin origins. True to the artist’s wider deception, a closer look reveals each name contains the letters of the word “plastic” hidden within its title.

Observed in its entirety, Beyond Drifting: Imperfectly Known Animals is an ingenious metaphor for the ubiquity of plastic in the anthropocene, encapsulating in miniature the much larger problem of an imperfect world. Barker’s intention — namely, for beguiling her viewers by way of beauty — is to shock them with the urgent reality of what it represents. “I’m tricking them,” she says, “and I want them to remember it enough so that when they’re buying plastic, they’ll be mindful to reduce their plastic footprint.”

We have ten years to save our planet. Photography has a vital role to play. Decade of Change — the global award and collaborative exhibition dedicated to documenting the climate crisis — is now open for entry.