Goodman Gallery presents four days of films by Shirin Neshat from 20 to 24 June; the various films, many of which have not been screened for years, will be available from 7 pm each day — a full programme can be found here. To mark the event, we share an interview with Neshat, from earlier this year, in which the artist reflects on her oeuvre and her most recent body of work — Land of Dreams.

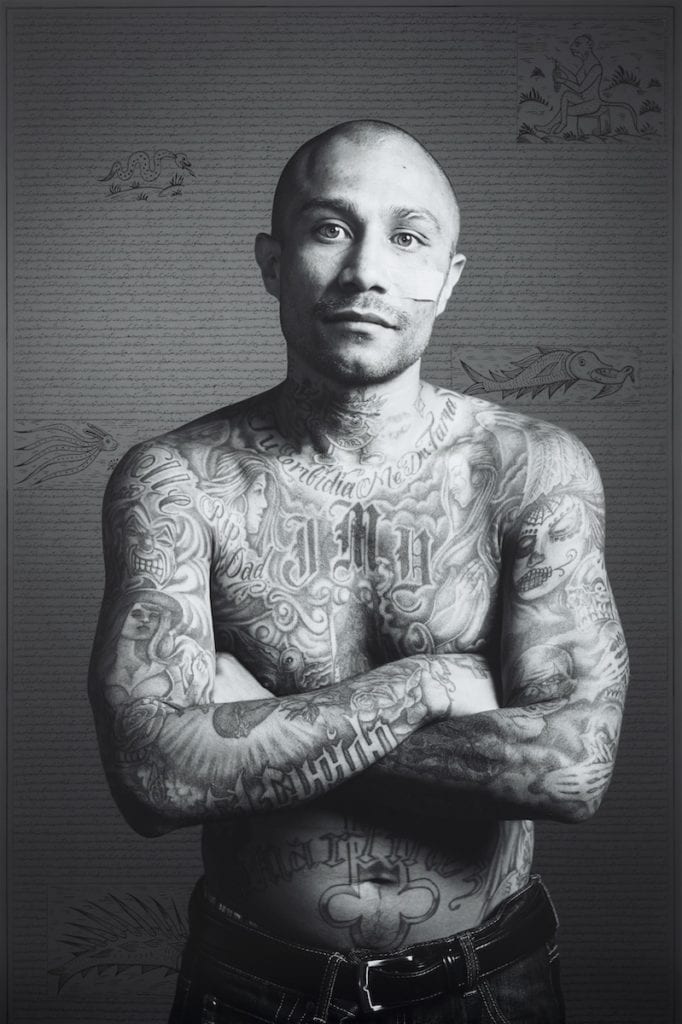

Shirin Neshat wanders across the upper floor of the Goodman Gallery in London, gesturing around her. Dozens of faces gaze down, staring out intently from the walls of the space. An ex-convict with a tattooed torso, arms folded; a serene-looking man with mental health problems, neck gently crooked; a woman, whose blonde, blow-dried locks fan outwards, clutching a pup to her stomach. “It is like a portrait of America,” says Neshat, referencing the salon-style installation. “It is not about the single person but the whole – I find that very moving when you are in a room surrounded by faces that are looking at you.”

The experience is profound: despite the subjects’ anonymity, locking eyes with them is intimate — they surround us, and it is hard to look away. As Neshat, who oozes elegance with thick, black kohl framing each eye, glides across the space, she speaks of her subjects with fondness. “This guy, look at his face, isn’t he beautiful,” she exclaims, “and this woman, I love her. That guy, he owned the restaurant, where we shot the photographs in Albuquerque.” The images depict an assortment of characters who Neshat recruited and who found her by chance. Hispanic, Native American, white, black, rich, poor, young, old, mentally ill, homeless — collectively, the individuals represent a segment of American society, monumentalised in the artist’s often almost life-sized frames.

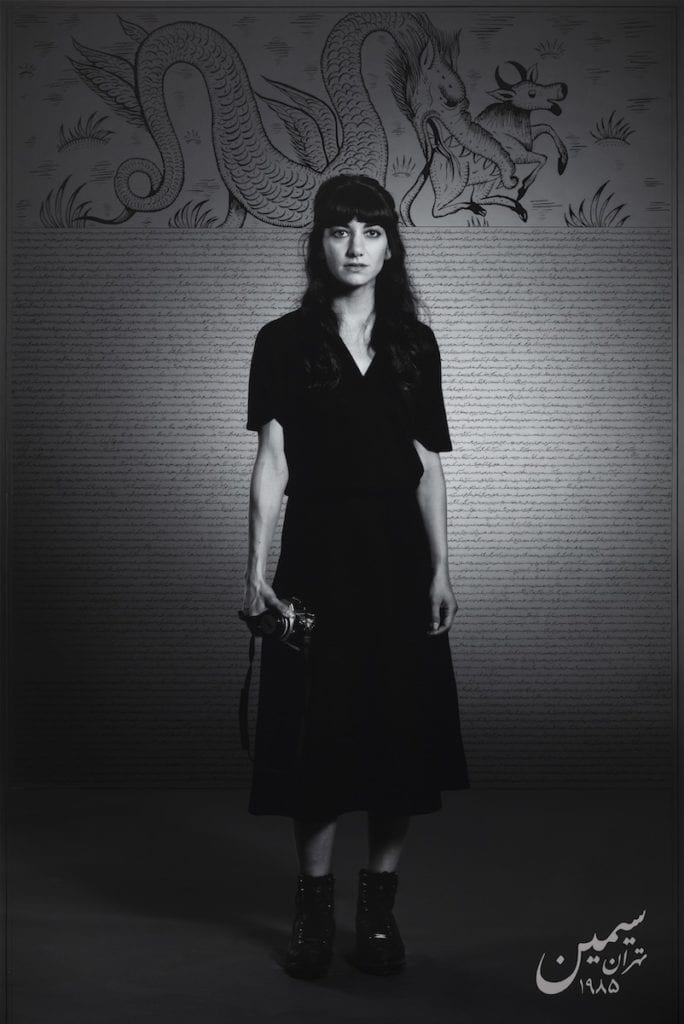

The photographs, over 60 of which were on show at Goodman Gallery, London, were taken by Neshat, who will be Master of Photography at Photo London 2020. They are a fragment of the 111 portraits that make up her most recent project Land of Dreams, however, in the context of the series, the images belong to someone else — an Iranian photographer named Simin: the fictional protagonist of two video installations exhibited on the lower floor of the gallery space, which comprise the remainder of the work. The films follow Simin, a covert Iranian agent, posing as an art student, as she photographs individuals at home across New Mexico, recording, and eventually, penetrating their dreams. Simin is one of many Iranian agents reporting back to a secluded bureaucratic colony where Americans’ dreams are collected and analysed to reveal the country’s “malice”, as Neshat describes it. “In many cultures, especially those that are religious, governments have been interested in dreams because they are regarded as a way of reading the future: as though God projects the future through people’s dreams — calamities, rivalries, environmental catastrophes,” she explains.

“I felt exhausted by the criticism and judgement. Employing magical realism, political satire, and dreams, is a means to escape all of that”

The narrative is fictional, but dips in and out of reality, a device embraced by Neshat since she began experimenting with it for her first feature film Women with Men (2009) —an adaptation of a 1989 Shahrnush Parsipur novel of the same name, which follows the unsteady lives of four female characters in pre-revolutionary Iran during the 1953 US and UK-backed coup that ousted the democratically elected leader Mohammad Mosaddegh. The story centres around Munis, Faeseh, Fakhri, and Zarin, and the effects of political upheaval on them. Neshat employs elements of magical realism, with the characters and their storylines veiled in symbolism, to make political statements that extend beyond the literal plot. “I felt exhausted by the criticism and judgement,” she says, referencing her earlier and more overtly political work, “employing magical realism, political satire, and dreams, is a means to escape all of that.”

Magical realism is rife in Land of Dreams, which is replete with symbols, metaphors, and layered meanings. The clinical and claustrophobic colony, where uniformed employees work silently and abide by strict rules, is emblematic of the suppressive culture of Iran. While the sweeping, open planes, traversed by Simin to find her subjects, embodies the myth of the American Dream, which is shattered by the difficult realities and nightmares of the individuals that she encounters. The character of Simin is herself a surrogate for Neshat, and visually she evokes her: a slight woman with ebony hair dressed in black; a camera slung around her neck as she moves from house to house searching for subjects — an approach that mirrors that which Neshat took to make the work. “Everything that you see [in the video installations] is my story — and the photographs depict the people I found,” she explains.

Neshat has always been present in her work, whether directly or via some other form — a muse, or a reference to her culture or past, which has been tumultuous. Born in 1957 in the city of Qazvin, just north-west of Tehran, Neshet grew up in a religious yet largely liberal Muslim household. In 1975, aged 17, she was sent to Los Angeles to finish school, before attending the University of California, Berkeley in San Francisco. Four years later, the Iranian Revolution shook Neshat’s home as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s conservative regime repressed a society that had become increasingly open to Western influence. The following year the Iran-Iraq war, which was provoked, in part, by the establishment of Khomeini’s Islamic Republic, began, and, in America, which actively supported Iraq, anti-Iranian sentiment intensified.

Neshat could not return home and found herself exiled in a place that was becoming increasingly hostile towards her. She built a life in New York, working at the independent art space the Storefront for Art and Architecture run by her former husband; she was, however, making little art of her own. In 1993, Neshat returned to Iran for the first time and was shocked by what she discovered: a country transformed under the tyranny of Khomeini. In response to this, and her attempts to make sense of it, Neshat’s artistic vision began to take shape.

In one of Neshat’s earliest series, the politically-charged Women of Allah (1993), the artist is the central protagonist. The haunting images — which depict veiled women, their bodies inscribed with modern poetry written in Farsi, holding, or standing aside, gleaming pistols — address conceptions of femininity in the context of the Islamic fundamentalism and militancy that had pervaded Neshat’s home. However, the artist’s breakthrough came with her black-and-white video installations Rapture and Turbulent (1999), the latter of which won a Golden Lion at 1999 Venice Biennale. Exploring a theme that would continue to dominate Neshat’s work, Turbulent interrogates the strictly defined roles of men and women in Iran with a female singer challenging societal restrictions via an impassioned performance, which interrupts that of her male counterpart.

Neshat’s work has largely focused on Iran and her complex relationship with it as a woman living in exile. However, the ascendency of Donald Trump, and the discrimination that has accompanied it, changed that, compelling her to turn her lens to America. She speaks of the shift she has observed across her host country: a divisive and discriminatory atmosphere driven, in part, by the current administration — Trump’s Muslim ban, for instance, or his unwavering commitment to constructing a border wall between Mexico and the US. The president has also exacerbated the historically fraught relationship between Iran and the US, with his economic sanctions, withdrawal from the nuclear deal negotiated by Obama, and, most recently, with the assassination of the country’s most powerful military commander, Major General Qasem Soleimani. “I felt that everything was changing in America,” reflects Neshat, ”a place where I had felt very safe and secure as an immigrant, despite knowing that there has been a long antagonism between Iran and the US”.

Likening the current political situation, in both the US and Iran, to “a theatre of the absurd,” Neshat decided that employing absurdity would be the most fitting way to approach the subject. “The way that Trump is acting in America parallels the absurdity of the Iranian government,” she explains. The resulting work is extraordinary. The dreams, around which the films’ narratives centre, are fantastical and transcend social divisions: “When you delve into such realms, the narrative becomes universal — all people dream. It is not possible to tie surrealism to one nation,” she explains. The dreamers, however, who are, or who are based on, individuals Neshat met while travelling across New Mexico, represent a sample of US society. A white, middle-class, Christian woman in her elaborately-decorated home, and an elderly, lower-middle-class man anxiously dreaming of a nuclear holocaust. A Native American mother whose nightmare of having her child taken away unfolds in an empty convent, where the US government systematically relocated Native American children to assimilate them. And finally, a displaced Bosnian woman verging on the edge of insanity, whose dreams and memories have become one.

“When you delve into such realms, the narrative becomes universal — all people dream. It is not possible to tie surrealism to one nation”

The female protagonists who populate Neshat’s work have always resisted repression, rebelling and escaping in myriad ways, from protest to madness. The film’s protagonist Simin is no exception: she eventually enters into her subjects’ dreams, despite being forbidden from doing so, and, on returning to the colony attempts to make sense of them in secret. “The biggest fighters in Iran today are women. The most unafraid people in Iran are women. I’ve always tried to say this,” Neshat explained in an interview with the LA Times, speaking of her commitment to challenging the Western perception of Muslim women as victims. In Land of Dreams, Simin disrupts the regimented world of the Iranian colony by allowing her curiosity to prevail: “She took her camera and she was free,” says Neshat. Simin may be read as a symbol of the refusal of Neshat, and Iranian women at large, to fall in line — to bow to social or political repression. The artist’s work has always signified defiance, and Simin’s dramatic exit from the colony, camera in hand, after her transgressions are discovered, likely represents this.

Ultimately, despite addressing the current situation in the US, Land of Dreams goes deeper. It stems from Neshat’s history of exile but speaks to the experience more broadly: exploring how fear and displacement are universal, crossing borders and social divisions. With the ascendancy of far-right politics and discrimination worldwide, the artist calls for her fellow artists to be politically conscious and aware of how their work fits into the contemporary discourse. With her distinct visual language – at once poetic and political, factual and fantastical — Neshat does just this. She addresses a host of urgent subjects in nuanced and thought-provoking ways.

Shirin Neshat Land of Dreams was on show at Goodman Gallery, London, until 28 March. Neshat will be Master of Photography at Photo London 2020.