Every year, BJP-online asks a selection of industry leaders to recommend the photobooks, exhibitions, and projects that stood out to them most. Here, we introduce Goto’s selection of five remarkable photographers in 2019

Yumi Goto is an independent curator, editor and researcher who specialises in photography made in areas of conflict, natural disasters and human rights abuses. Based in Tokyo, Japan, Goto often works with human rights advocates, NGOs, and international photo festivals and events throughout Asia.

To mark the end of 2019, Goto selects five artists who caught her eye at workshops, festivals and fairs around the world. “They have all engaged with their subjects to such an extent that the work has affected their lives,” Goto comments. “The distance between the photographer and subject has diminished so that the photographer is able to have a better understanding, which is then reflected in their work.”

Arun Vijai Mathavan

Millennia of Oppression

Engineer turned photographer Arun Vijai Mathavan’s project, Millennia of Oppression, is an evocative depiction of the lives of Dalit workers in India, the people who are responsible for dissecting corpses during post-mortem examinations.

“In India, the reality of this process is shockingly different from our perception. In almost all hospitals, a range of tasks, sometimes even the opening of the torso with the Y-incision, is done by semi-literate, low-level staff,” Mathavan explains. “My project proposes to shine a light on this unknown, shrouded world and to look at how this caste evolves during the time which takes shape in new practices”.

Millennia of Oppression was on show at this year’s Chennai Photo Biennale in eastern India, where the 30-year-old photographer exhibited 50 images that capture the lesser known side of death in India.

Paola Jiménez

Rules for Fighting

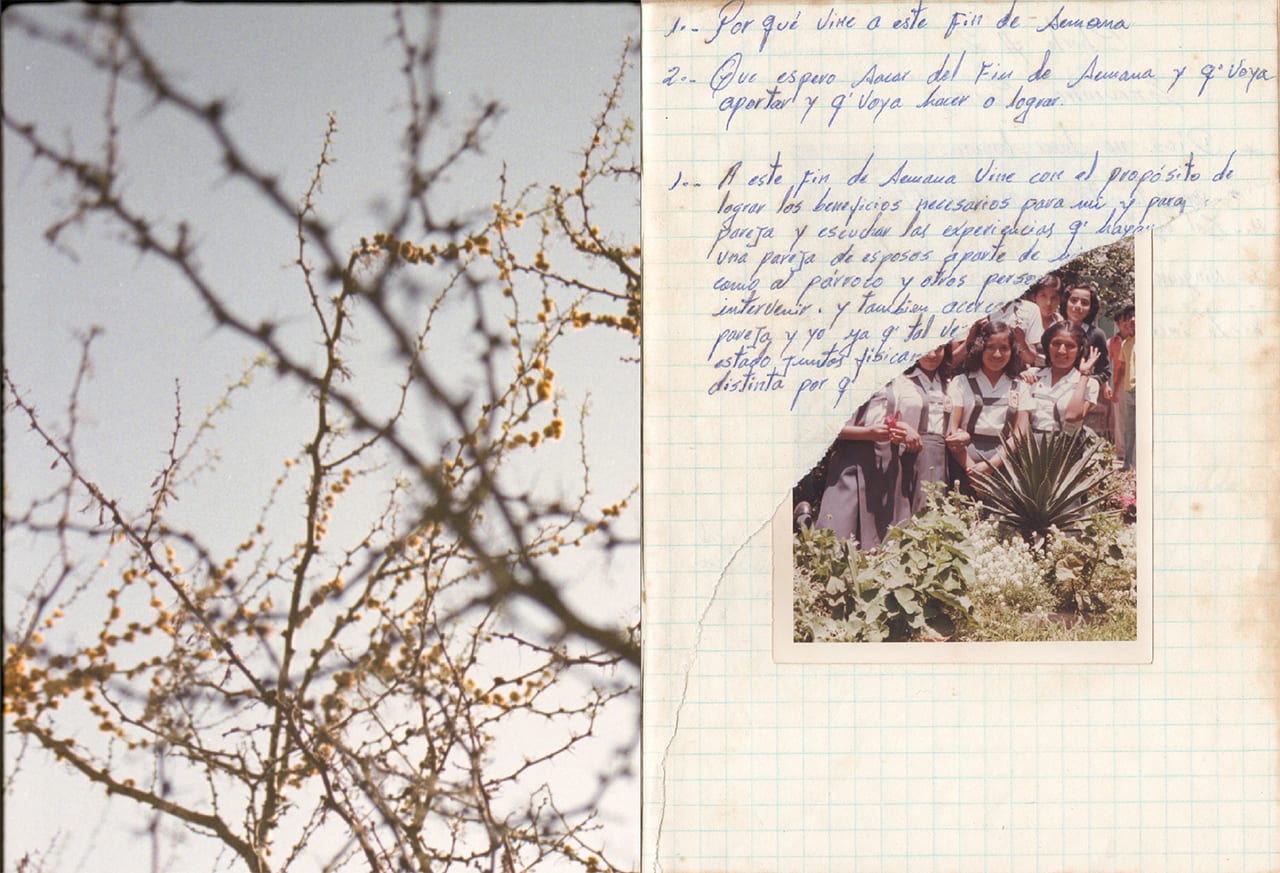

In February 1998, Paola Jiménez’ father was murdered in Lima, Peru. “My family was really shocked and they didn’t talk about the issue, so I grew up questioning lots of stuff about him and what happened,” write Jiménez, who was five years old at the time.

As an adult, Jiménez began to search for clues within her house, uncovering objects that belonged to her father, a police report, and a plastic bag full of undeveloped film rolls that amounted to 706 images. Combining these with her own images, archival materials and diary entries, Rules for Fighting is Jiménez’s attempt to communicate with her father after all these years.

Gao Shan

The Eighth Day

Gao Shan’s Paris Photo/Aperture award-winning photobook The Eighth Day, takes its title from a personal history: the day Shan was adopted by his mother. According to the photographer’s afterword, his relationship with his adopted mother was characterised by coldness and indifference, but recently he has begun to regard her as more than just a presence in his life. Using his camera not for cold observation but as an active tool in their relationship, Shan presents an intimate photographic document of their lives.

Seba Kurtis

Immigration Files

For the last decade, Argentinian photographer Seba Kurtis has been applying a personal and experimental approach to his continued exploration of immigration, partly instigated by the years he spent living as an illegal immigrant in Spain. His first book, Drowned (2011), was a series of sea-weathered negatives, echoing the tragic experiences of those who attempt to cross from Africa’s north-west coast to the Canary Islands. Heartbeat (2012) was an investigation into the immigration detection systems implemented by the UK Border Police — a human heartbeat detector.

In his latest series, Paraíso (2018), Kurtis captures the landscape where refugees arrive after the journey across the Mediterraean Sea. Using glitter and abstract shapes in the place of statistics and graphs, Kurtis redraws the death toll of those who attempt this dangerous route.

Liang Yingfei

Beneath the Scar

In 2015, Liang Yingfei’s close friend, H, was sexually assaulted during a charity hiking trip. When she reported it three years later in July 2018, it instigated the beginning of the me too movement in the charity sector, encouraging more people to come forward with their experiences.

Behind the scar is Yingfei’s attempt to record and present the traumatic experiences of sexual abuse, and the impact of it on future life and work. The project is divided into three parts. The first is a collaboration with H, using words and polaroids to record life after abuse. Part two is a reconstruction of memories by other victims, and part three is a video piece in which strangers read out collected experiences about sexual abuse. “I hope this can serve as an entry into the hearts of sexual assault victims, while the viewers will develop a more comprehensive understanding of sexual assault through empathy,” writes Yingfei.