Tira was a 48-year-old transgender woman, disfigured by surgical operations, and Dayang was an outcast street boy with no family. They lived in a squatted courtyard near an airport, just off a very busy junction in Jogyakarta, Indonesia. They are the subjects of Luca Desienna’s personal project, My Dearest Javanese Concubine.

Born in Italy, Luca Desienna has been a freelance photographer since 1998. One of the co-founders of Gomma Books in 2004, he has produced four Gomma magazines plus two publications devoted to black-and-white photography, MONO volumes I and II, working with image-makers such as Roger Ballen, Antoine D’Agata, Trent Parke, Daido Moriyama, and Anders Petersen.

Petersen has described Desienna’s My Dearest Javanese Concubine as “a story full of vitamins and warm energy”, and the series was shown at the official selection of the 2012 Arles Voies Off. Now, as My Dearest Javanese Concubine is made into a book by BlowUp Press, we revisit this Q&A originally published on BJP-online in February 2018.

–

BJP: How did you get into photography?

Luca Desienna: I graduated in Graphic Design and Photography in Italy, but I got truly into photography way after that. I started taking pictures because I needed to for myself – during a delicate time of my life, the camera quickly became my companion, my friend, my ally. I remember I sold my motorbike and bought a camera and a Vespa instead and that was it, my initiation really. London was my stage at that time, after the streets, I started taking the camera into people’s life, into hermetic parties and households. I always felt the need to show how certain concealed realities live.

BJP: Many of your projects are in black-and-white – why did you get into monochrome?

LD: I always liked the fact that I am the one who develops my own films. I love this kind of 360 degrees ownership of the creative process. I also like the chemical side of it, the mixing of the devs, the little adjustments you can try to personalise your style a bit further, the never-ending experiments. I like the touchability of the process. I found it very romantic.

Other than that I think black-and-white photography has the ability to transfuse the photographer’s inner moods. In a way it’s a more artificial represention of the world, because the world does exist in colour, but at the same time it’s more faithful to the photographer’s inner vision of the world itself, because he’s able to imprint his own perceptions, his feelings and his longings.

BJP: When did you start work on the Javanese Concubine series? Where was it shot?

LD: I started in 2010 and it ended in 2012. It was shot on the outskirts of Jogiakarta, Central Java.

BJP: How did you find the subject? What’s her story?

LD: I was shooting and following the life of Maryani Oriono, a local transgender woman who opened the first Islamic school for LGBT people in Java. What was supposed to be a two-day commission became a longterm project. I saw a community and a reality completely new to me. Coming from Europe, I had a misconceived idea of what it means to be transgender, and also what it is really like living in a Muslim country. There I started to see transgender people who adopt children from the street, who unite together in order to broaden their social acceptance, who gather together to pray to Allah, and who teach the Koran. All of this was quite mind-blowing for me.

I met Tira and Dayang while following Ines, one of Maryani’s pupils. As soon as I saw Tira and Dayang, I was completely blown away by their relationship. Tira was tidying the picture frames in her one-room house while Dayang was sleeping on the mattress on the floor. After a short while, she sat beside him and by the way she lowered down close to him I felt their unique bond. She sat down as a lioness would sit beside her beloved – a mixture of tenderness and protection, and a distrust of the outside.

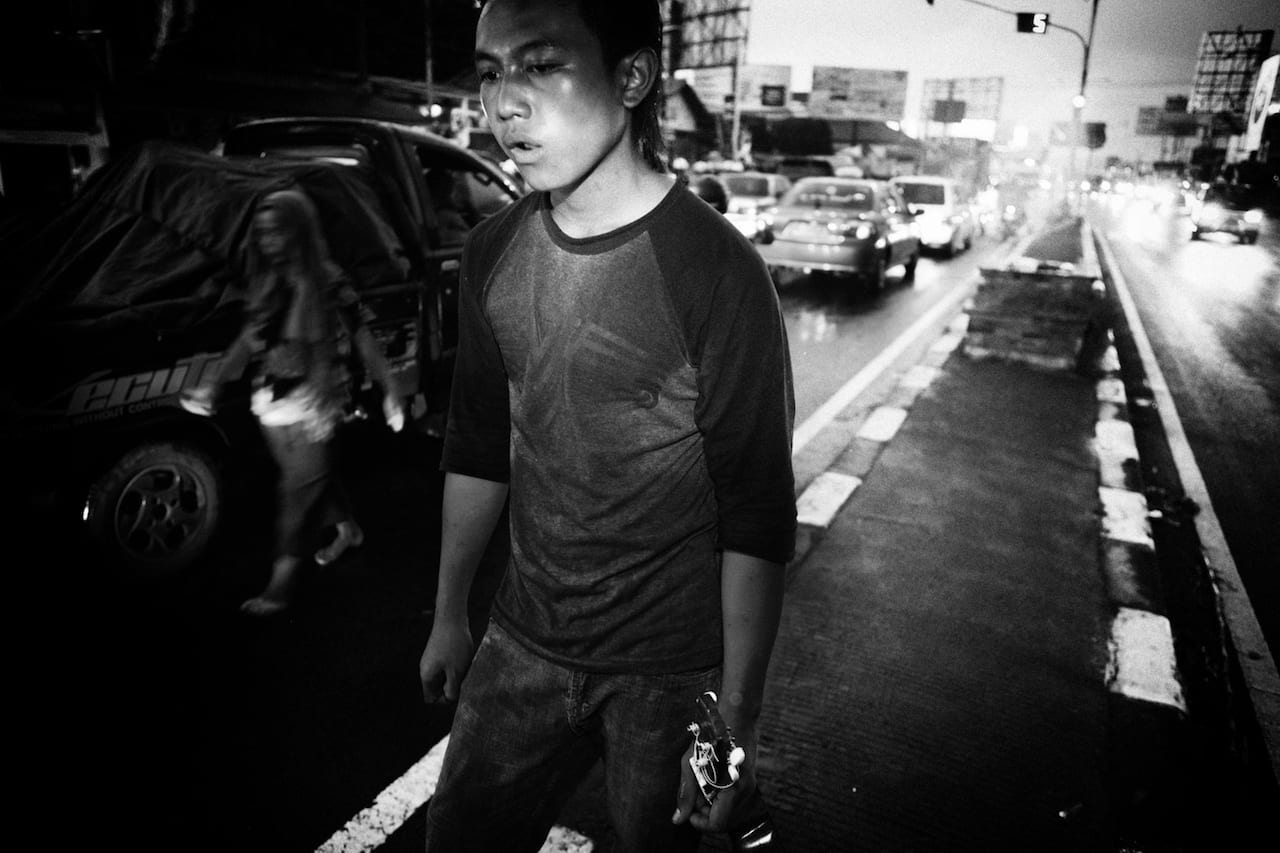

Tira was a 48-year-old male to female transgender, disfigured by lousy surgical operations; Dayang was an outcast street boy with no family and no place to stay. They lived in a squatted courtyard near an airport, just off a very busy junction. They had met four years before on the street, and since then had been sharing everything – their home, their pains and their hopes. Dayang and Tira were two people living together, supporting and loving each other through an uneasy life.

BJP: How did you build up enough trust to shoot them?

LD: I think you need to be a human before being a photographer, simple as that. The images are a contour of the relationship you are building. You also need to feel attracted to the people you photograph. Interweaved. This has nothing to do with physical attraction, it has to do with something that goes under the skin. For example with Tira and Dayang, I felt we had the same vision of what love really is and can be.

It takes time, and you need to forget time. Time is an obstacle that needs to be replaced with a sense of belonging. And you can’t belong to a place if you have a plane to take. So I changed all my schedule and plans, and completely submerged myself in the moment. I lived with them, I got drunk with them, I shared a part of my life with them, and I still feel honoured to have witnessed such a unique existence. For me Tira and Dayang were and always will be two modern heroes, heroes who have struck a pathway through what we regard as normal and accepted.

BJP: How did you work?

LD: I didn’t use a big camera, so I just followed her constantly. Everywhere, all the time. I felt I had to document everything, I couldn’t portray only a slice of her life. During one of our first meetings Tira told me: ‘Luca, people don’t know what I am, and they don’t want to know…they just stop at the entrance and stay there, staring…staring at the surface’. So I didn’t want to stay there at the entrance. I had the privilege to enter Tira and Dayang’s world, to go beneath the surface to a world made of pain, joy, intolerance, poverty, scars, prostitution, mortality, and God.

BJP: Some of the images are really intimate – how did you shoot them? Why did you want to include them?

LD: In that small space that they called their home they could be themselves. I didn’t want to put barriers or limitations to what could or couldn’t be shot and neither they did. So during shooting I just kept shooting, everything, all the time what was happening. The intimate moments are an important element in someone’s life, they show the bond, the eagerness, the longings. I was so immersed into the shooting that I don’t think I was totally aware of what I was actually shooting, I kind of lost myself into it, like a Stanislasvki actor. In post-production I decided to add a few of those images to the story because I feel they represent a part of their life.

BJP: Could you say more about the book?

LD: This story has to be shown in a form of book. This has nothing to do with egotism, it has to do with the responsibility I have towards Tira and Dayang. Misinterpretation and misjudgement are too easy when we enter certain delicate territories. I worked hard on the text – I wanted to add something about this experience. The first time I saw Tira I saw what everyone else could see, but with time I entered her world. I felt her soul, her persona, and by the end of the shooting I forgot about the surface and truly saw her. I hope I can transmit this to the viewers, and the best means to achieve this is through a book.

BJP: What do you hope to say with this project?

LD: I want the moments of tenderness to hit the viewer in the guts. I want to challenge our comfort zone, our conception of the nature of love and the meaning of beauty. One of the first things I felt when I met Tira and Dayang was respect – respect for their strength and tenacity, and especially for their effort to retain a joie de vivre. I hope I can show that along with all their drama and pain.

BJP: What does Tira make of the story?

LD: Unfortunately she passed away in 2012.

mydearestjavaneseconcubine.com

blowuppress.eu