“They were unconscious: we undressed them and when the captain of the flight gave us the order we opened the door and threw them out, naked, one by one,” says Adolfo Scilingo, a former Argentine naval officer.

Over 5000 people were killed in this way by the Argentinian dictatorship during the so-called Dirty War of 1976 to 1983, in which it attempted to wipe out all opposition. Suspected dissidents and subversives were sedated and put on planes for so-called Death Flights; their journey ended when their unconscious bodies were thrown into the Rio de la Plata or the sea.

Argentina’s desaparecidos – or “disappeared” – have stories that are almost beyond belief, and it’s only thanks to the testimony of survivors that justice has started to be done. Miriam Lewin is one such witness. A political activist who fought the dictatorship, she was just 19 when she was kidnapped and taken to a detention centre, where she stayed for one year.

She was then transferred to the infamous ESMA facility – originally the Navy School of Mechanics (“Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada”), but then the dictatorship’s largest secret detention centre. She was one of the few to come out alive. “We were deprived of all our rights, we were neither alive nor dead, no one knew where we were,” Lewin told RAI (Italian Radio Television) on 26 April this year. “We have been victims of all kinds of crimes and tortures.

“When we were in the concentration camp, every Wednesday a group of prisoners were taken to a location in Patagonia, so they told us – but it was a lie, they brought them to die,” she continued. “As Jews who did not believe to be destined to the concentration camps, we could not believe this reality. We deceived ourselves to stay alive with the illusion of a better destiny. ”

Miriam Lewin, former Desaparecida, portrayed in her former cell inside Virrey Cevallos, the concentration camp in which she was detained in for almost a year by the Argentine Air Force. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Lewin is now a journalist and has collaborated with Italian photographer Giancarlo Ceraudo, on Destino Final, an investigation that has led to the arrest of three pilots, and has now been published by Schilt. Originally trained as an anthropologist, Ceraudo first went to Argentina in 2002, after the country’s economic collapse, at a time when “the question of dictatorship was on you even without searching for it”.

Miriam Lewin, former Desaparecida, portrayed in her former cell inside Virrey Cevallos, the concentration camp in which she was detained in for almost a year by the Argentine Air Force. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Lewin is now a journalist and has collaborated with Italian photographer Giancarlo Ceraudo, on Destino Final, an investigation that has led to the arrest of three pilots, and has now been published by Schilt. Originally trained as an anthropologist, Ceraudo first went to Argentina in 2002, after the country’s economic collapse, at a time when “the question of dictatorship was on you even without searching for it”.

Keen to find answers, he contacted Lewin and suggested they try to track down the Death Flight planes. Initially she was surprised by his proposal, and not particularly enthusiastic. “No one had ever thought of where the aircraft used for the Death Flights were taken when it was over,” she says. “I was wondering how could help us to locate them, at that time it seemed to me a madness. He replied ‘To get to the killer pilots’.”

They started to collaborate from 2003, starting a global hunt which resulted in finding five aircraft – two in museums in Argentina, and three sold to a Luxembourg company (of one one remains in Luxembourg, another was sold on to the UK, and the most important ended up at Fort Lauderdale in Florida). Their book depicts the aeroplanes and some of the evidence they built up, as well as other aspects of the dictatorship’s crimes and their aftereffects.

“One plane, used for the postal service, was found with the original flight plans that, once decoded by Enrique Pigneto, allowed us to identify the suspect flights departing on Wednesdays,” Ceraudo explains.

“For example to cover Buenos Aires-Punta Indio, a distance of 150 kilometers, four hours flight had been allowed. The following charge lead to the arrest of three pilots, who are currently waiting for judgment.”

Destino Final by Giancarlo Ceraudo is published by Schilt Publishing, available in stores and online for £40.

Skyvan PA-51, one of the five planes of the Argentine Naval Prefecture used for death flights during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship. According to the investigation, this aircraft operated the flight on 14 December 1977. Fort Lauderdale, Florida, United States, 2013 © Giancarlo Ceraudo, courtesy of the artist

Skyvan PA-51, one of the five planes of the Argentine Naval Prefecture used for death flights during the 1976-1983 military dictatorship. According to the investigation, this aircraft operated the flight on 14 December 1977. Fort Lauderdale, Florida, United States, 2013 © Giancarlo Ceraudo, courtesy of the artist

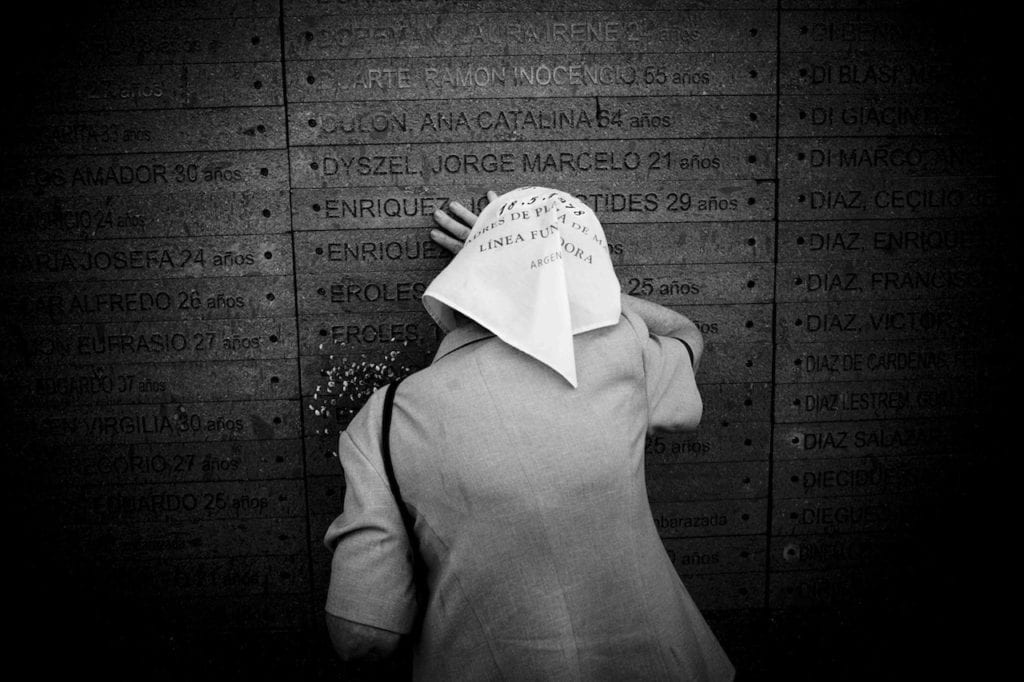

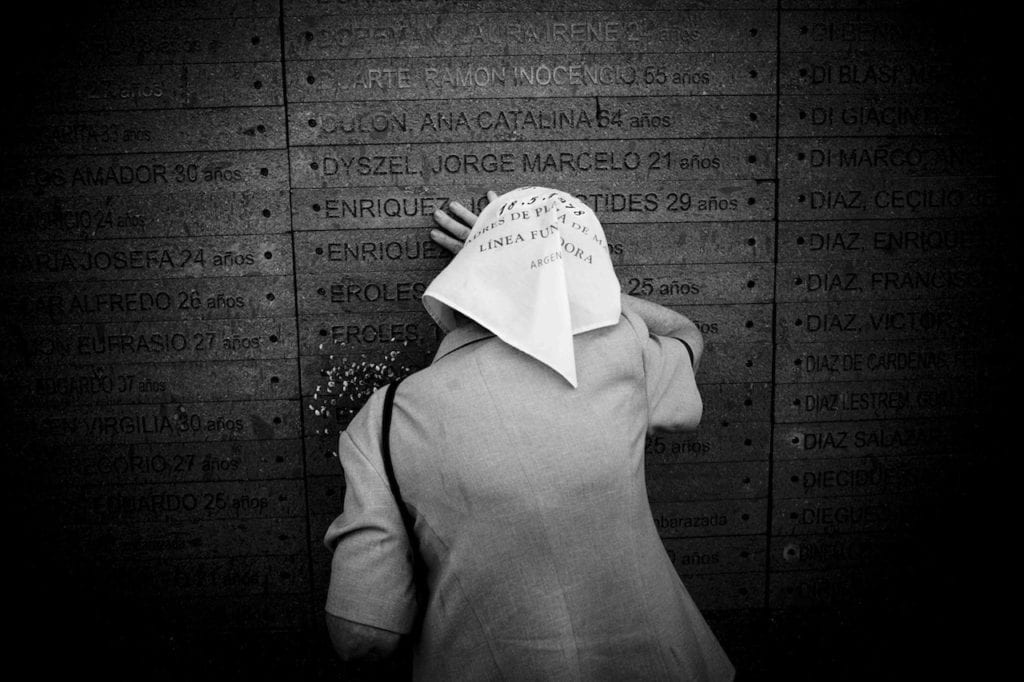

One of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo – a group of mothers whose children disappeared – cries on her son’s name, which is inscribed on the wall of the Park of Memory, the Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism located along the coastline of the Río de la Plata river. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

One of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo – a group of mothers whose children disappeared – cries on her son’s name, which is inscribed on the wall of the Park of Memory, the Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism located along the coastline of the Río de la Plata river. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Von Wernich, wearing a bullet-proof vest, enters the courtroom before the verdict. The court found him guilty of complicity in seven homicides, 42 kidnappings, and 32 instances of torture, and sentenced him to life imprisonment. La Plata, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Von Wernich, wearing a bullet-proof vest, enters the courtroom before the verdict. The court found him guilty of complicity in seven homicides, 42 kidnappings, and 32 instances of torture, and sentenced him to life imprisonment. La Plata, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

People holding some photographs of Desaparecidos at a public rally during the anniversary of the 1976 military coup. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 24 March 2011 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

People holding some photographs of Desaparecidos at a public rally during the anniversary of the 1976 military coup. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 24 March 2011 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

A forensic anthropologist examines the remains of a body recovered from a mass grave. The Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team is a non-governmental, not-for-profit, scientific organisation that applies forensic sciences – mainly forensic anthropology and archaeology- to the investigation of human rights violations in Argentina and worldwide. EAAF was established in 1984 to investigate the cases of at least 9000 disappeared people in Argentina under the military government that ruled from 1976-1983. © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

A forensic anthropologist examines the remains of a body recovered from a mass grave. The Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team is a non-governmental, not-for-profit, scientific organisation that applies forensic sciences – mainly forensic anthropology and archaeology- to the investigation of human rights violations in Argentina and worldwide. EAAF was established in 1984 to investigate the cases of at least 9000 disappeared people in Argentina under the military government that ruled from 1976-1983. © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

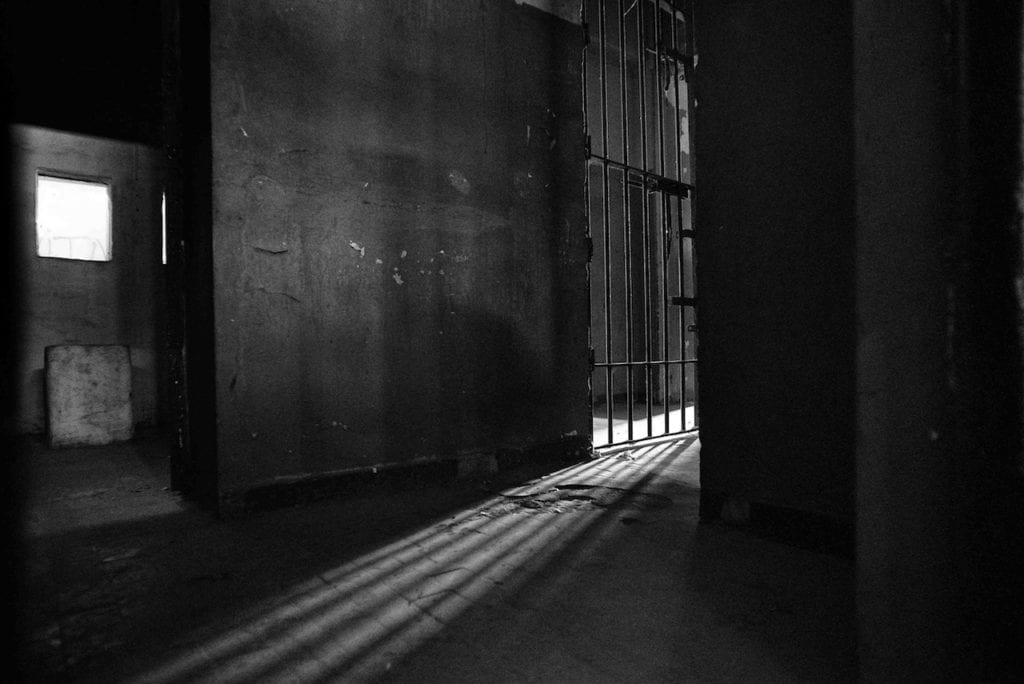

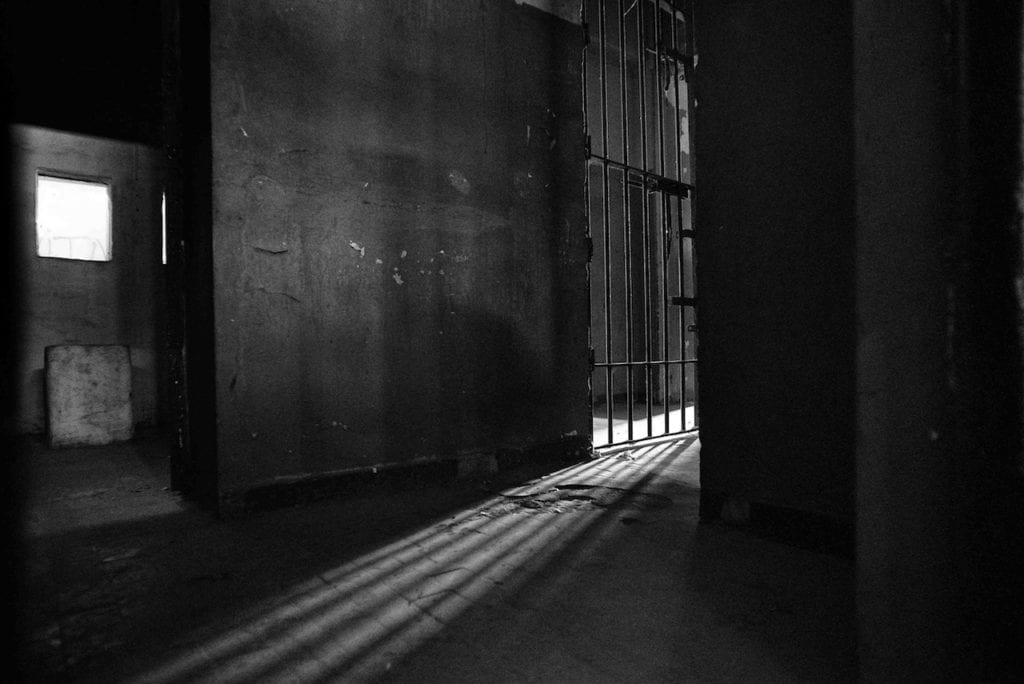

Inside view of Pozo de Banfield, a concentration camp where around 300 people were held prisoner, including many pregnant women. Their babies were taken at birth and given to families connected with the military regime to adopt. Banfield, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, 2015 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Inside view of Pozo de Banfield, a concentration camp where around 300 people were held prisoner, including many pregnant women. Their babies were taken at birth and given to families connected with the military regime to adopt. Banfield, Buenos Aires Province, Argentina, 2015 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Horacio Bau’s funeral. Forensic anthropologists returned his remains to his family 30 years after his disappearance during the dictatorship. Trelew, Chubut Province, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Horacio Bau’s funeral. Forensic anthropologists returned his remains to his family 30 years after his disappearance during the dictatorship. Trelew, Chubut Province, Argentina, 2007 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/ Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

A group of policemen at the entrance of the Tribunal Oral y Federal Nº 5 during the third trial for crimes against humanity committed at the ESMA. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

A group of policemen at the entrance of the Tribunal Oral y Federal Nº 5 during the third trial for crimes against humanity committed at the ESMA. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Victor Basterra was kidnapped and brutally tortured at the ESMA. He has been photographed in the office of Miguel Adolfo Donda, one of the most brutal torturers of the barracks, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist

Victor Basterra was kidnapped and brutally tortured at the ESMA. He has been photographed in the office of Miguel Adolfo Donda, one of the most brutal torturers of the barracks, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008 © Giancarlo Ceraudo/Schilt Publishing, courtesy of the artist