Over the course of his glittering career, David Bowie sold over 140 million records; receiving nine UK platinum discs and five in the US. He was inducted into The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, the same year attaining the Brit Award for an Outstanding Contribution to Music.

When considering the iconography of this artist, there is just something wrongheaded about a Sir David Bowie. Despite his many personas, Bowie’s image remains one of extraterrestrial otherness – and admission into the British ruling class not only presents the potential for accusations of ‘selling out’, but seems to place him geographically within the UK. His artistic locale feels altogether more indistinct.

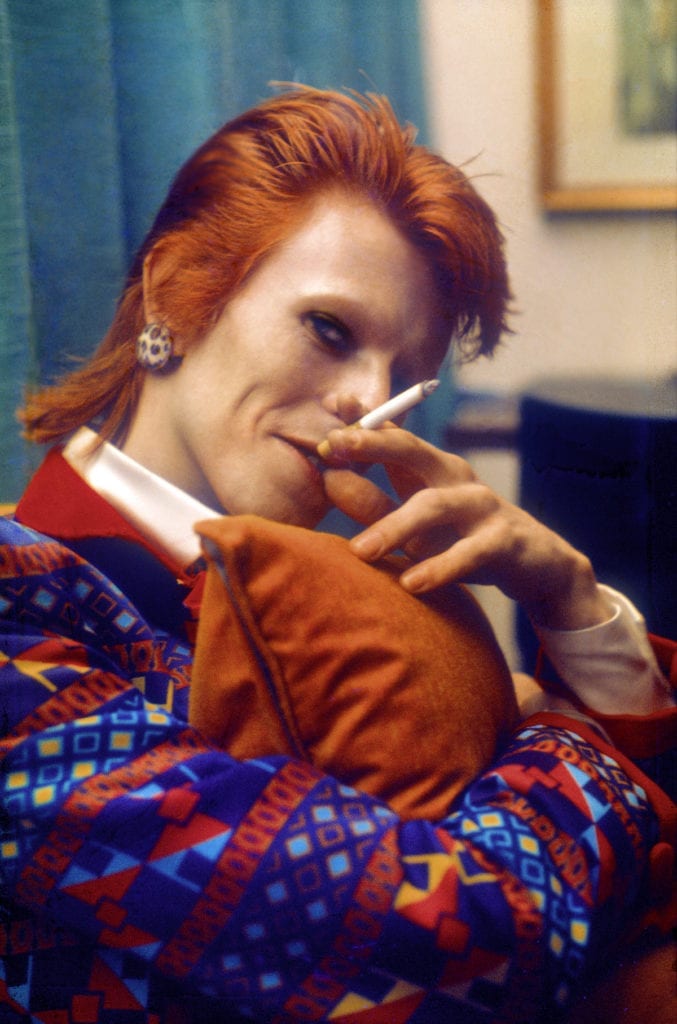

A still from the promo for The Jean Genie, San Francisco, October 1972 © Mick Rock

This is summarised in the movie, ‘Hedwig and the Angry Inch’ (2001), when the eponymous lead – a transgender punk-rocker from East Berlin – highlights the cultural impact of Bowie: ‘Late at night I would listen to the voices of the American masters; Toni Tennille, Debby Boone, Anne Murray – who was actually a Canadian working in the American idiom. And then there were the crypto-homo rockers: Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, [and] David Bowie – who was actually an idiom working in America and Canada’.

Icon, idiom or artist? How about all three?

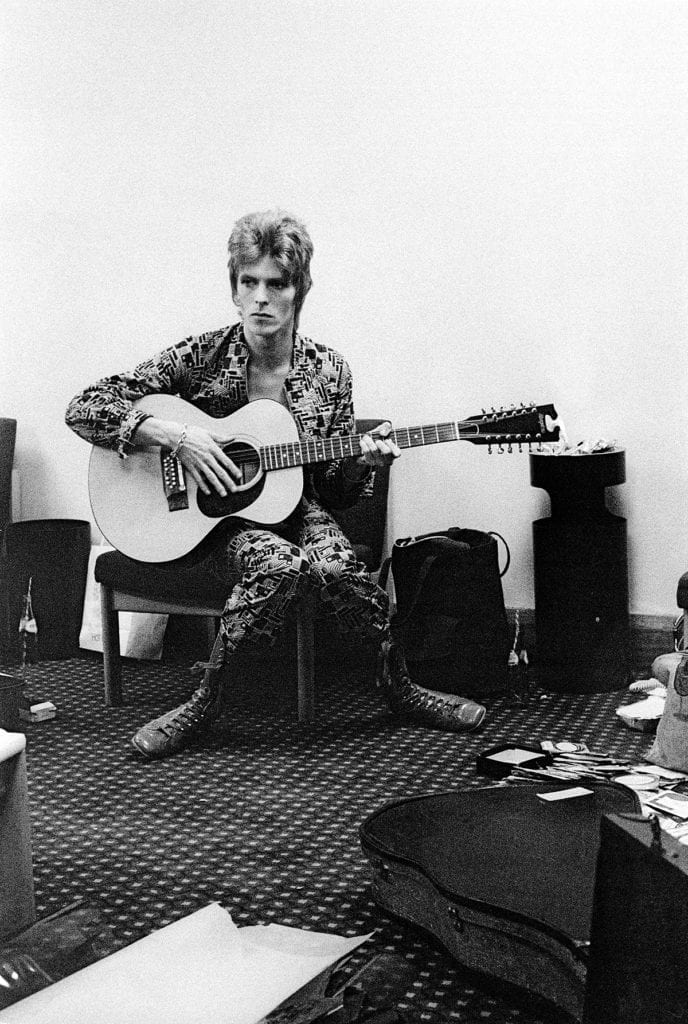

What is certainly clear, is that the ubiquitous acceptance so clear after Bowie’s death was not present when the Ziggy Stardust persona took to the stage in the 1970s, and this is the period Mick Rock’s photos tell us about. The photos depict a deeply divisive performer – one who is keen to carve out their own oeuvre, sponging up as many different influences as possible.

Rock himself describes this artistic drive in the intro to the book; ‘David used to talk of himself as a Xerox machine, picking up impressions all over the place. He brought in a lot of elements: the Warhol thing, The Velvet Underground, Jacques Brel, Kabuki, the Living Theatre, A Clockwork Orange. Lindsay Kemp was a huge influence. And of course the futuristic space thing, which Roxy Music got into as well.

‘David absorbed things so fast. He made the concoction so rich and thick.’

His songs provided a public intellectual voice for many people who felt they didn’t otherwise fit in – most specifically within the LGBT community. His outrageous sartorial choices and sci-fi musical theatre placed him off the beaten track – as the essential outsider’s poster boy: An image of otherness that those communities felt they owned, and a brilliant artist whose story morphed and reinvented itself with each album.

As Danish film director, Lars von Trier put it in a 1999 interview ‘When I was younger, I was fascinated by David Bowie […] He’d managed to construct a complete mythology around himself. It was as important as his music.’

David Bowie now stands as the archetypal art pop musician: a multi-instrumental creative director whose vision is borne out as much in the artwork, performance and videos as in the recorded music itself. This is both the basis and legacy of his iconography.

Maybe the final word should go to Rock again, who remained friendly with the singer up to the end.

Mick Rock: ‘Initially I was inspired by his music, and then I was fascinated by his aura. I felt hypnotised by all the mutating and shifting around. In truth, the persona interested me more than the personality, coupled with the naked ambition.

‘It’s all there in the Ziggy lyrics. He wasn’t thinking about money, he was thinking about stardom. He was projecting powerfully. And of course when he made Ziggy Stardust, which is all about stardom, he was not a star. That was the record that made him a star.

‘You’ve got to remember how young we all were. I first met David forty-two years ago, when the world was a very different place. Psychologically it was a very impressionable time. What everyone now accepts as modern pop culture was brand-new, and certainly my brain was wide open.

Too much LSD and hatha yoga, no doubt!’

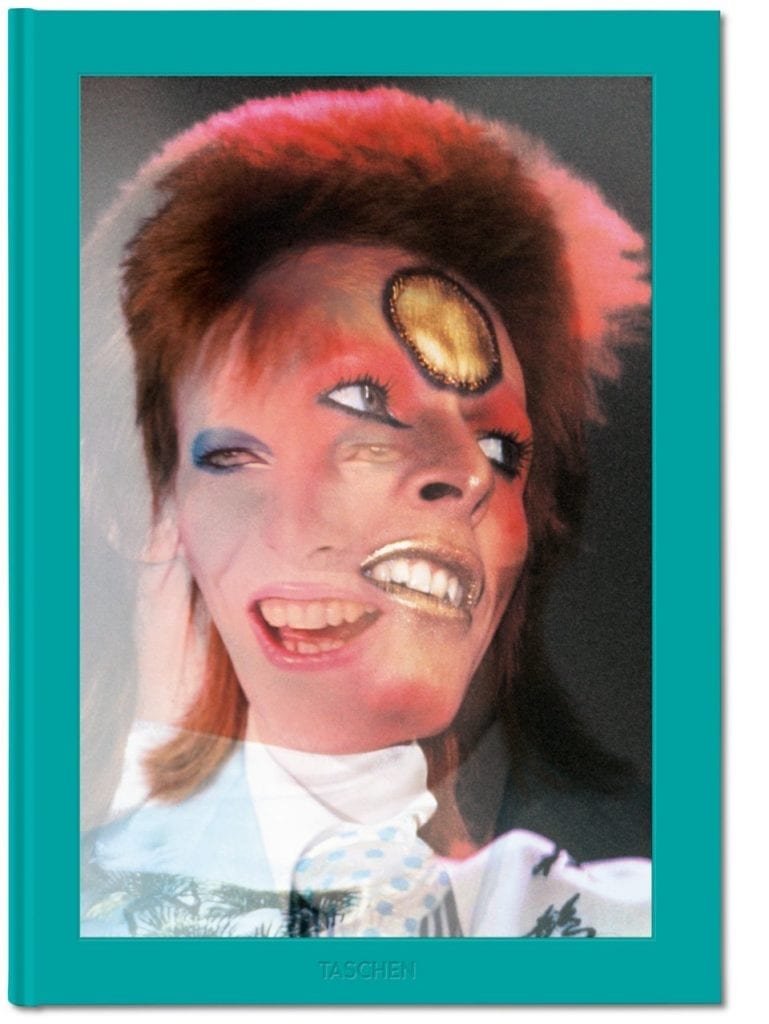

Mick Rock. The Rise of David Bowie, 1972-1973 is released by Taschen priced at $4,000 (Edition of 1,772 + 200 APs). For more info, visit here.