When Vogue 100: A Century of Style opened at London’s National Portrait Gallery last month, featuring Josh Olins’ portraits of Kate Middleton for June’s edition of British Vogue, The Guardian’s art columnist, Jonathan Jones, questioned whether they should be classed as works of art. “A Vogue cover shot is not a serious portrait,” he wrote on 2 May. “Nice face, nice clothes… but is a glossy picture of Kate Middleton in any way a serious work of art?”

Can the same ever be asked of, for example, Alberto Korda’s images of Che Guevarra? Among the most iconic portraits of a revolutionary ever taken, are they not portraits worthy of a gallery hook?

His portraits have been shown in 58 exhibitions over the course of five decades; indeed, many are held in private collections and museums around the world. Are Hinz’s images of Muhammed Ali not serious portraits? What about his portraits of Andy Warhol?

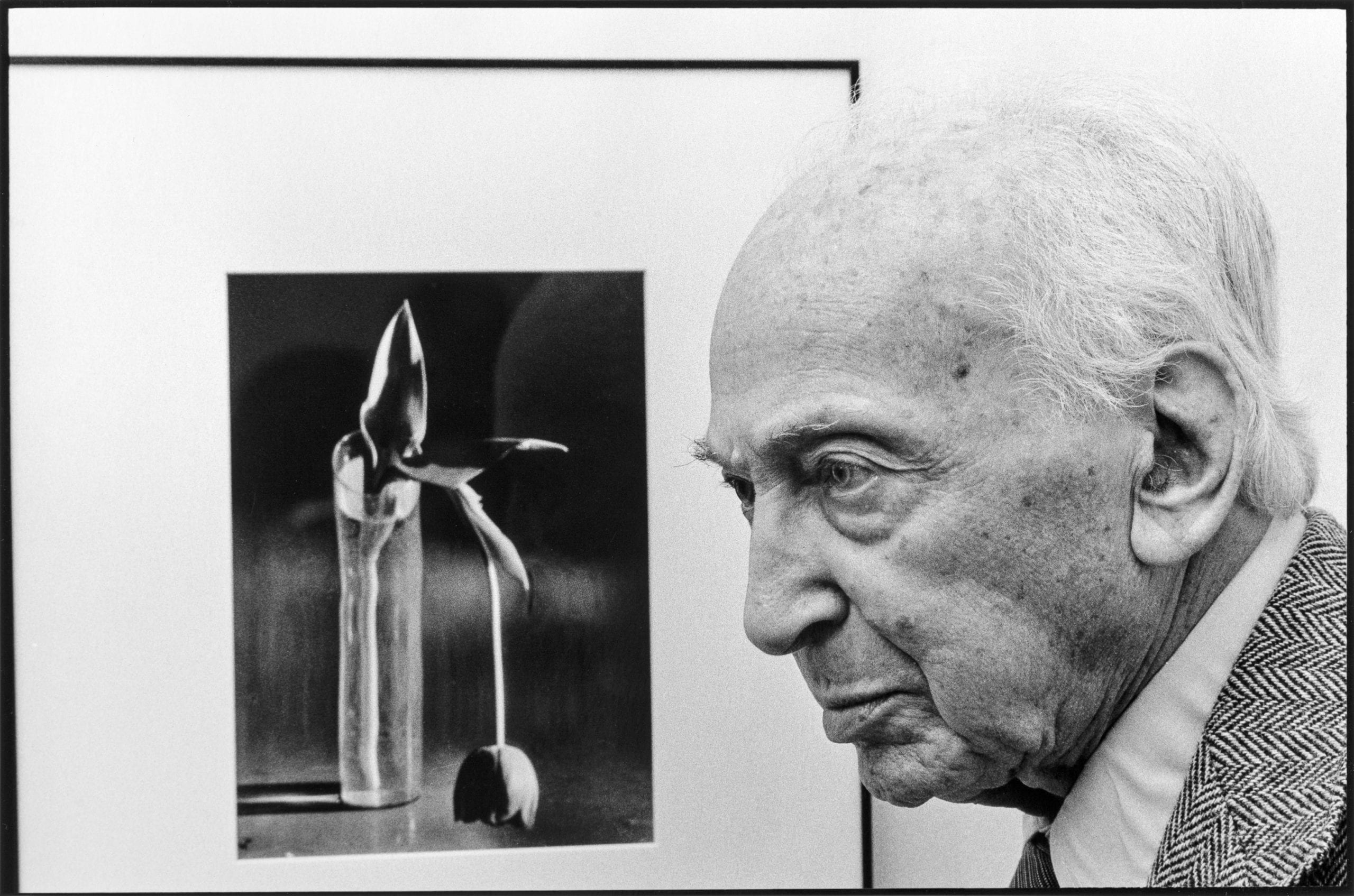

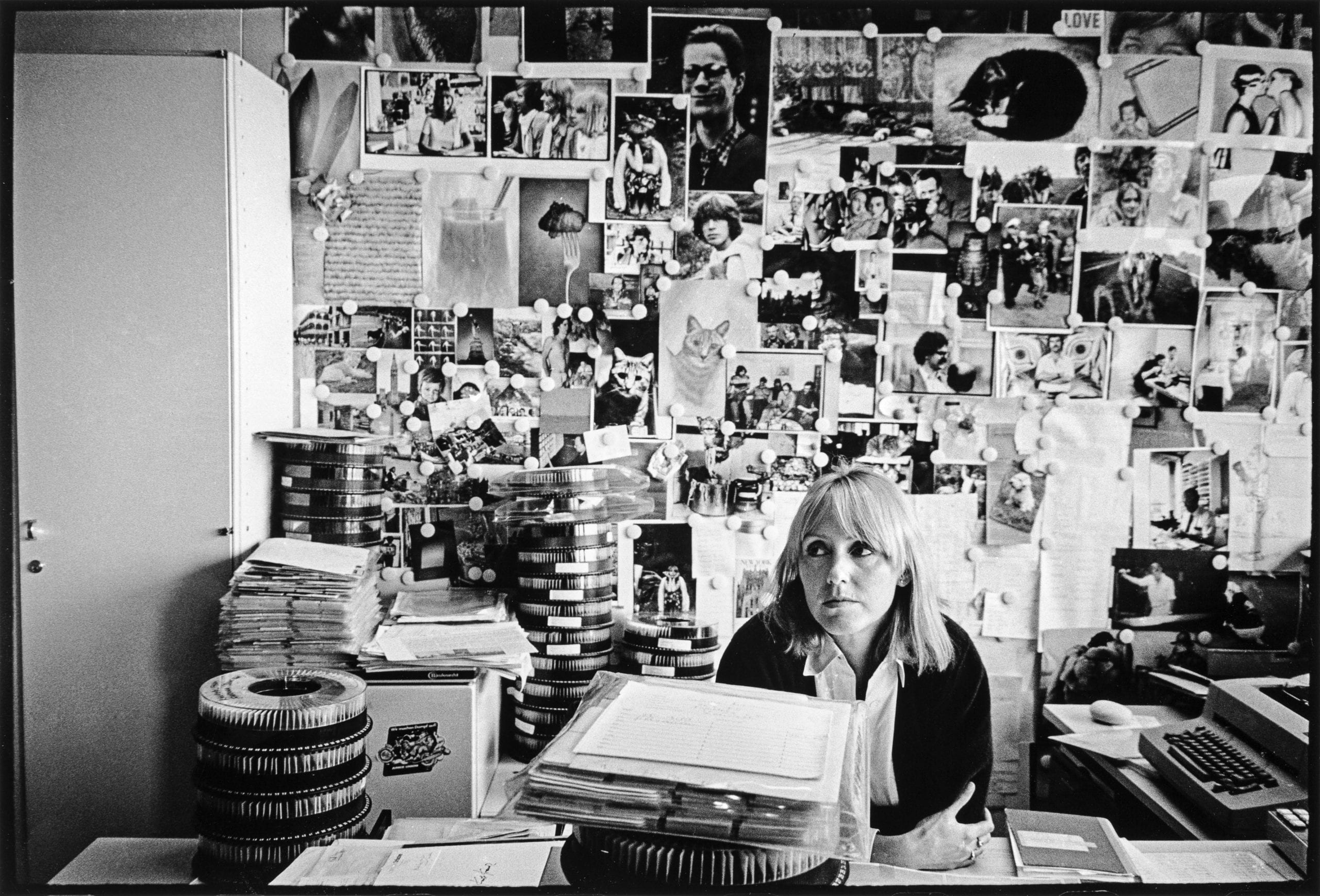

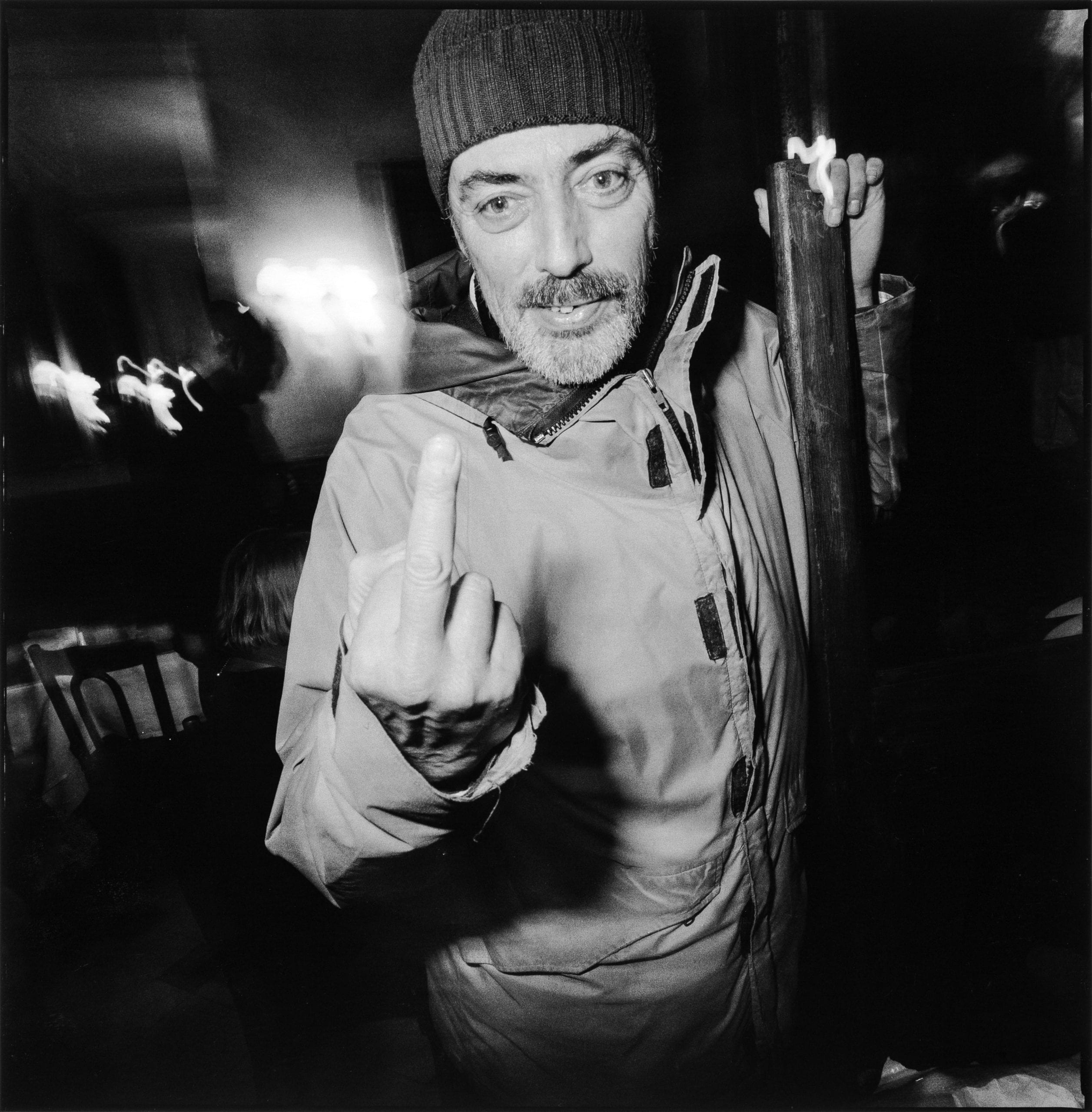

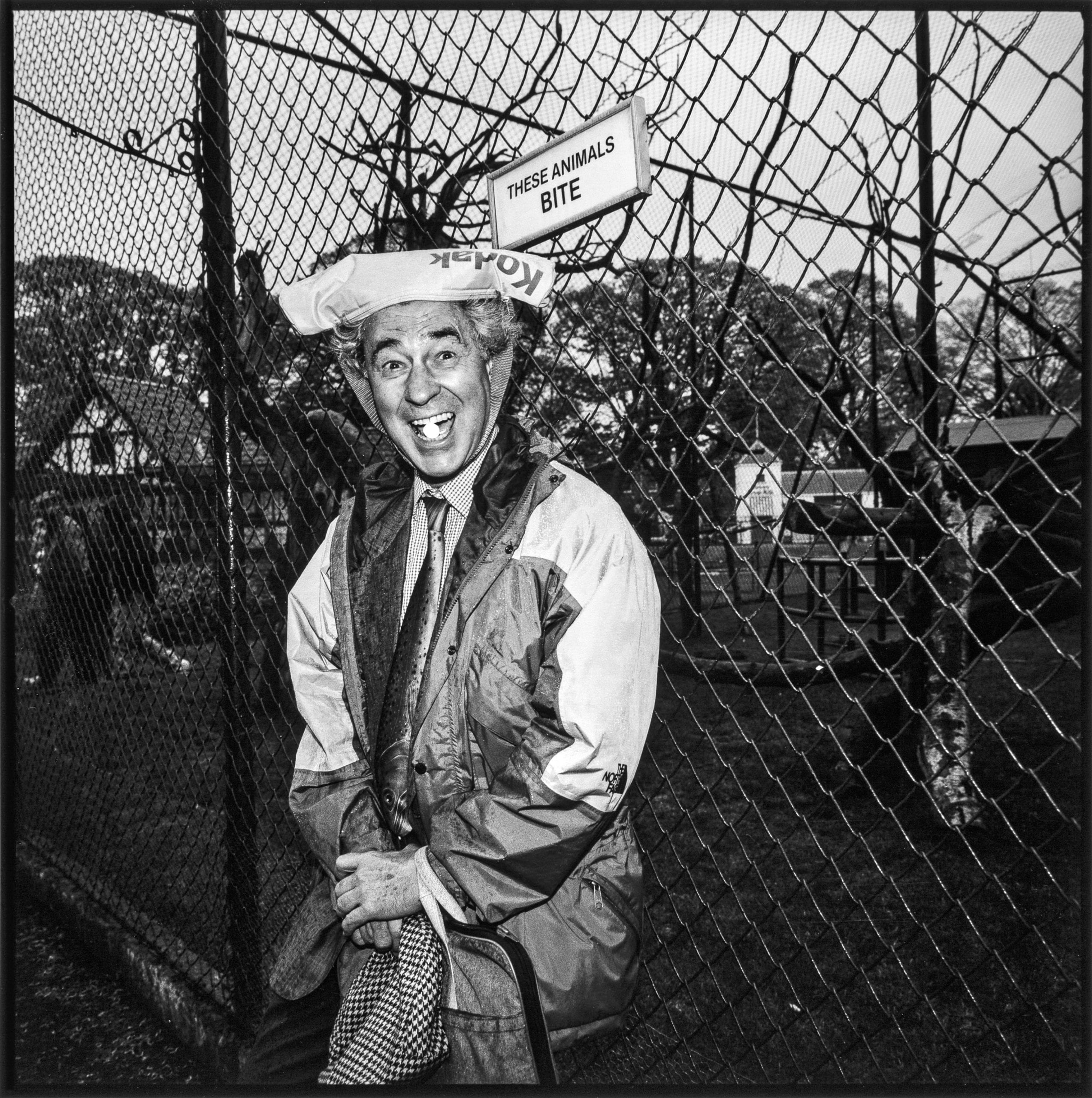

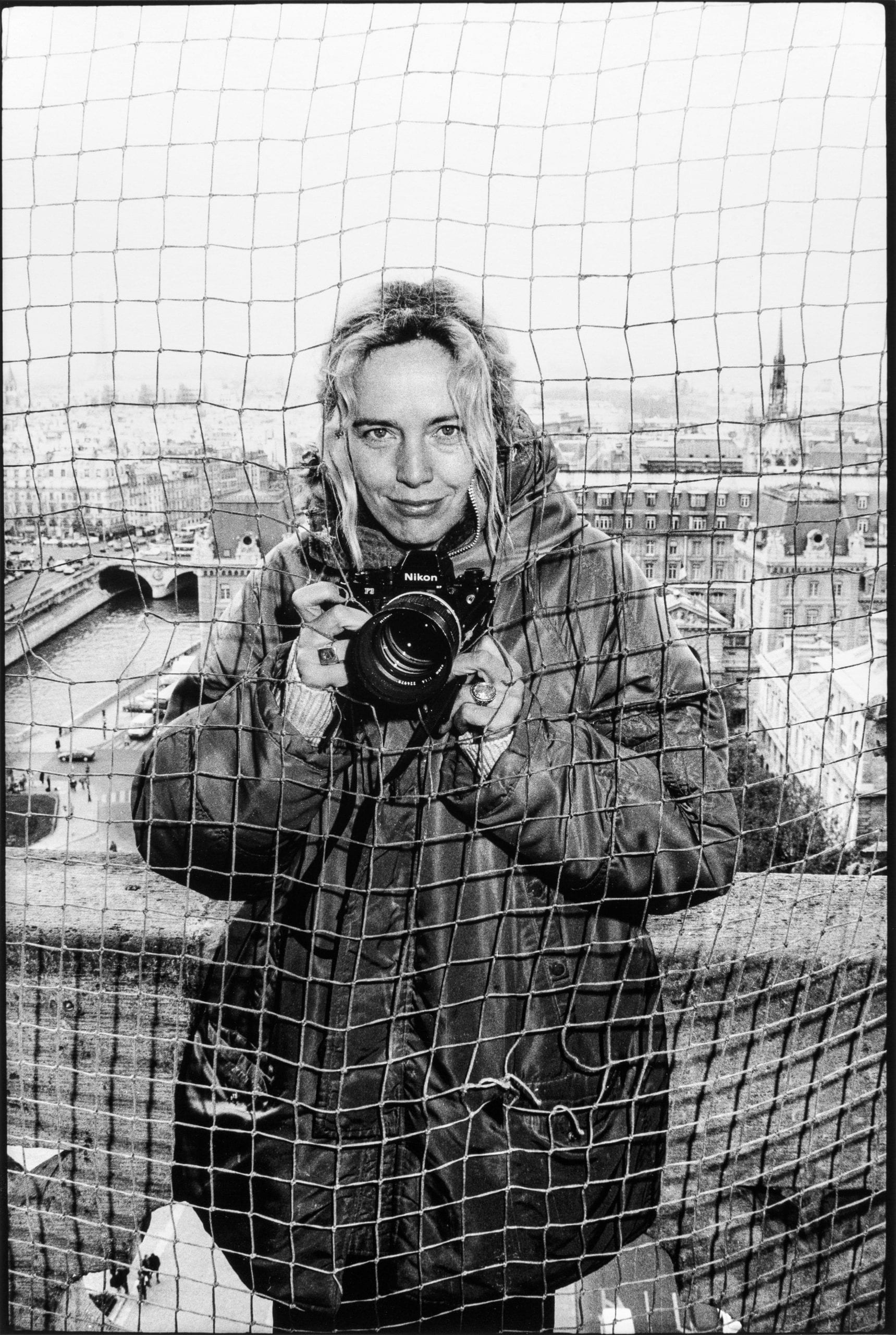

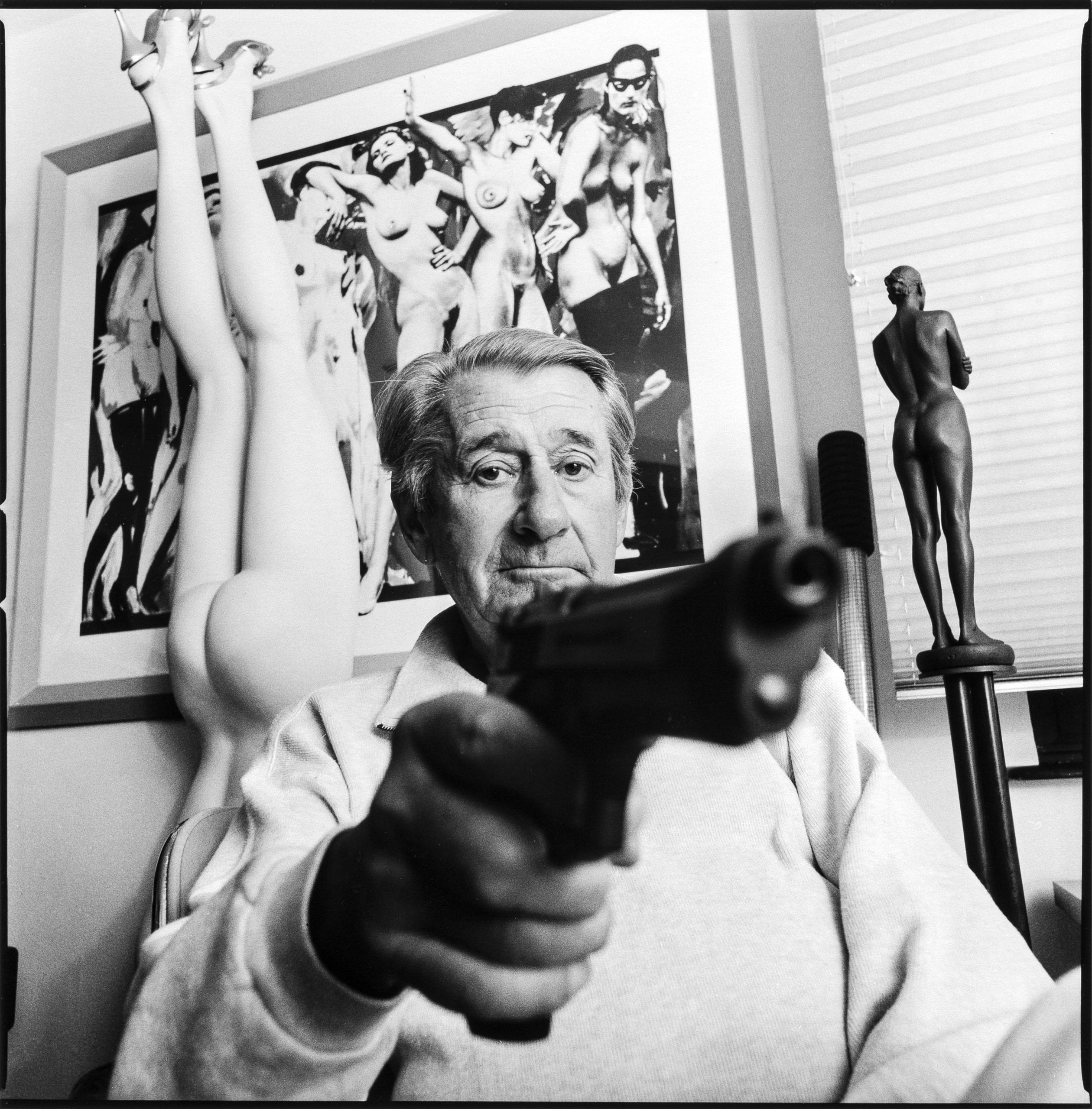

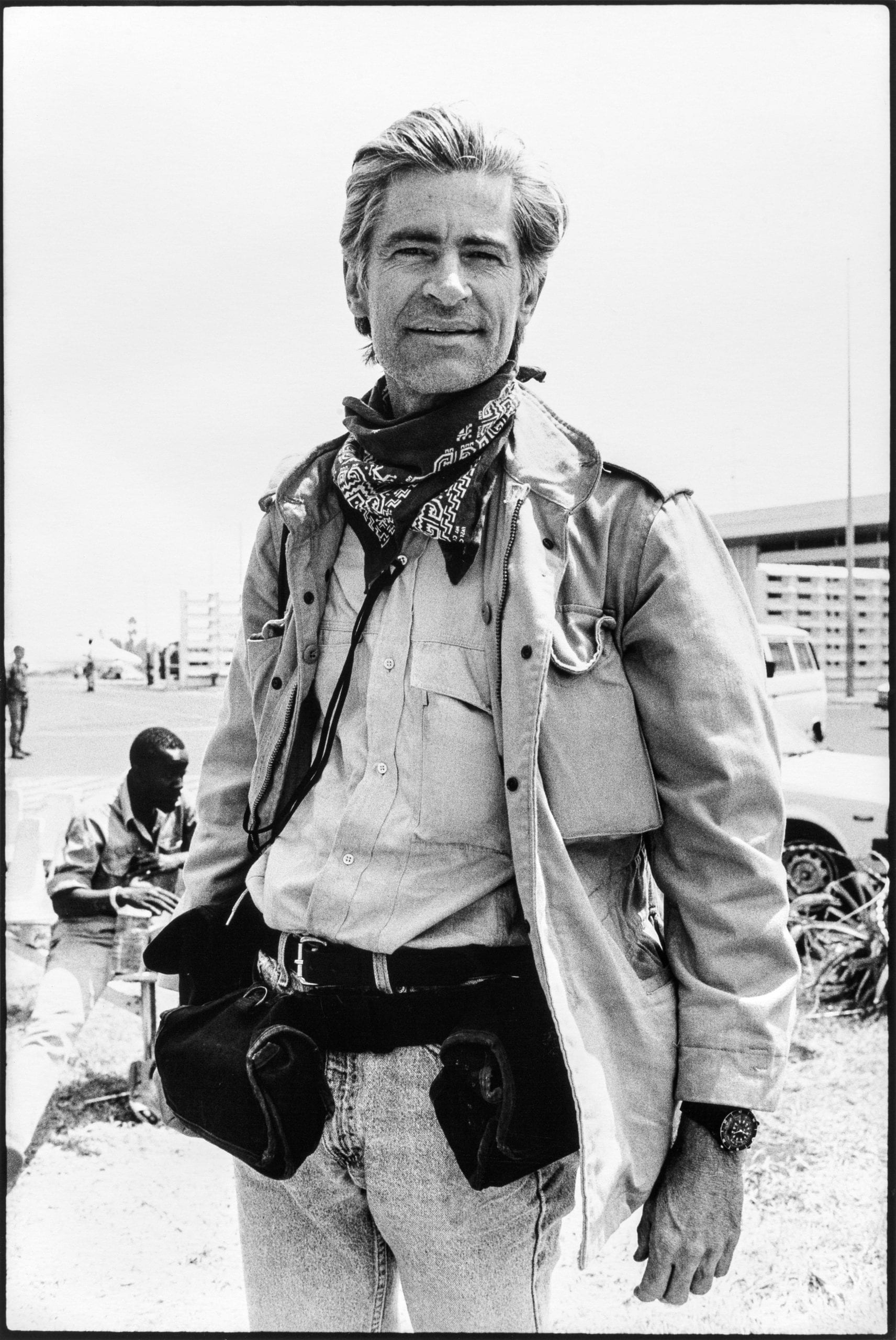

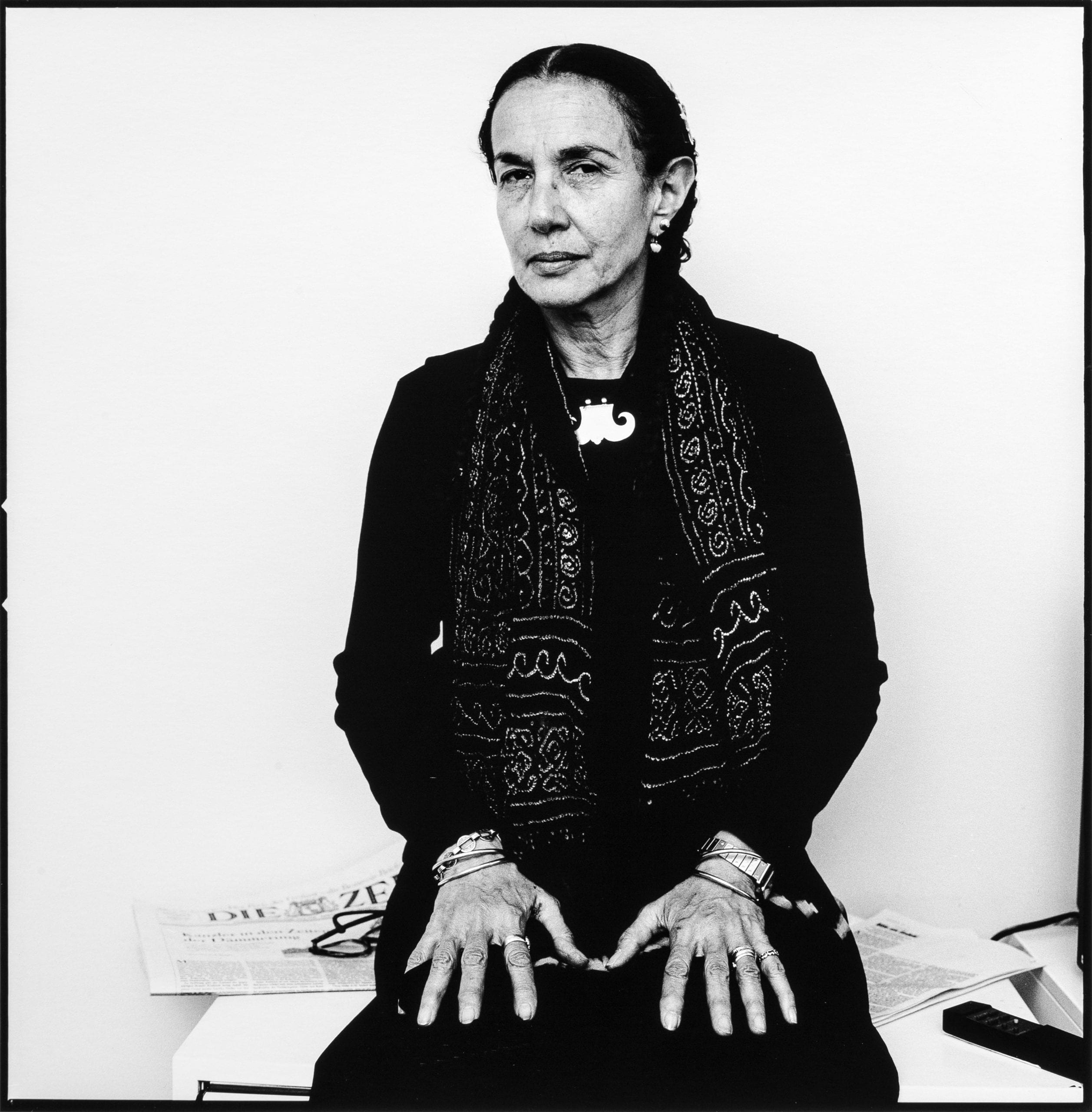

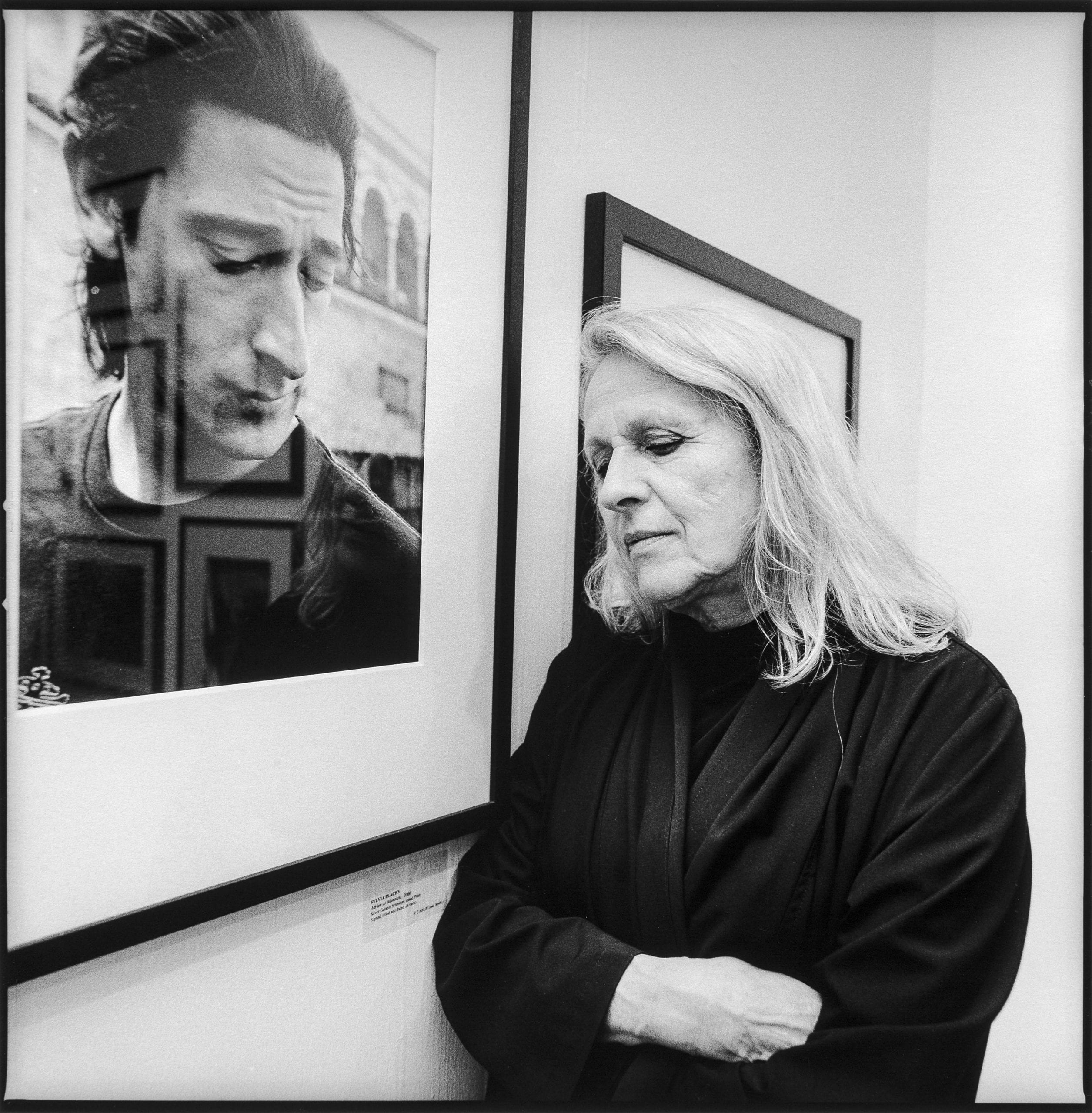

Over the years, while carving a name for himself as one of the most talented ‘people’ photographers of modern times, Hinz also turned his lens on fellow photographers – chroniclers who, like him, captured some of the most compelling images of the age.

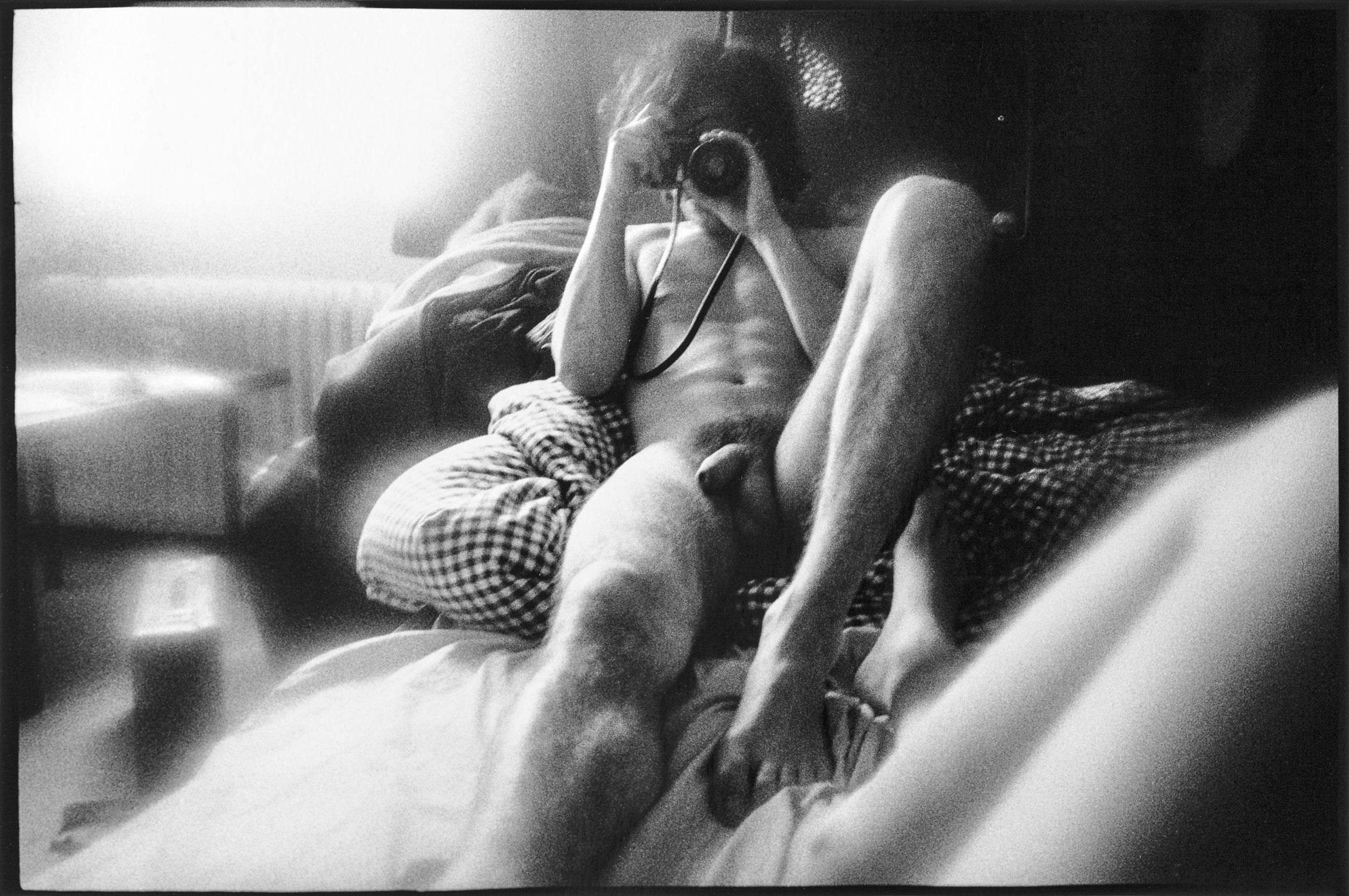

He captured fellow image-makers in quiet moments, at work in their studios, and casually in the street. He often captured “stolen moments” – snapping fellow image-makers unawares – and has even turned the lens on himself.

“It’s a unique collection of the most renowned photographers of the second half of the 20th century and early 21st century,” according to the book’s publisher, Lammerhuber, describing it as “a summit meeting of individuals who sustain humanity’s memory with their images”.

As a child, Volker and his sister would spend the day playing at the beach, or swimming in the river. “From time to time I caught little fishes,” he recalls. “It was an idyllic childhood.”

“Even my mother, in later years, started to paint and exhibit at local venues. But photography as art was not familiar to me as a child – certainly not before I first saw the magazine Twen. It was an exciting, popular monthly magazine that featured photography in double pages for the first time in Germany.”

Under conscription, Hinz was drafted into the army, where he served for 18 months. “I met a comrade who was a photographer – he explained to me the function of a camera. It was during that time that I bought my first camera and took my first pictures of my comrades. This was in 1968, in the city of Rendsburg.”

Later he offered me a job as a political photographer in Bonn. Two years later, the art director of Stern, Rolf Gillhausen, noticed my work and asked me to join as a staff photographer. After four years at Stern, I quit and went to the US. Four months later, I was reassigned to Stern to cover North and South America for eight years until 1986.” Hinz took his last photo for Stern in 2012.

Lois flew to my home in Hamburg from Vienna, and we both dived into my archive: 40 years of photography, 180 square meters of prints, slides and negatives. We looked through some prints and found a picture of Richard Avedon’s shoetrees, taken at the Paris workshop of the famous shoemaker, John Lobb. Lois asked me if I had more pictures of photographers and my answer was yes,” says Hinz.

Lois came to see me again in Hamburg, looked through the pictures, and took 480 prints with him to Vienna. Then I flew to Vienna and, together with the graphic designer, Lois and I put together a final selection for the book.”

Over nearly half a century, Hinz gathered what is clearly a treasure beyond his workday assignments – a treasure of shots of international photographers whose own art impressed him. But it’s perhaps this description of Hinz that sticks in my mind.

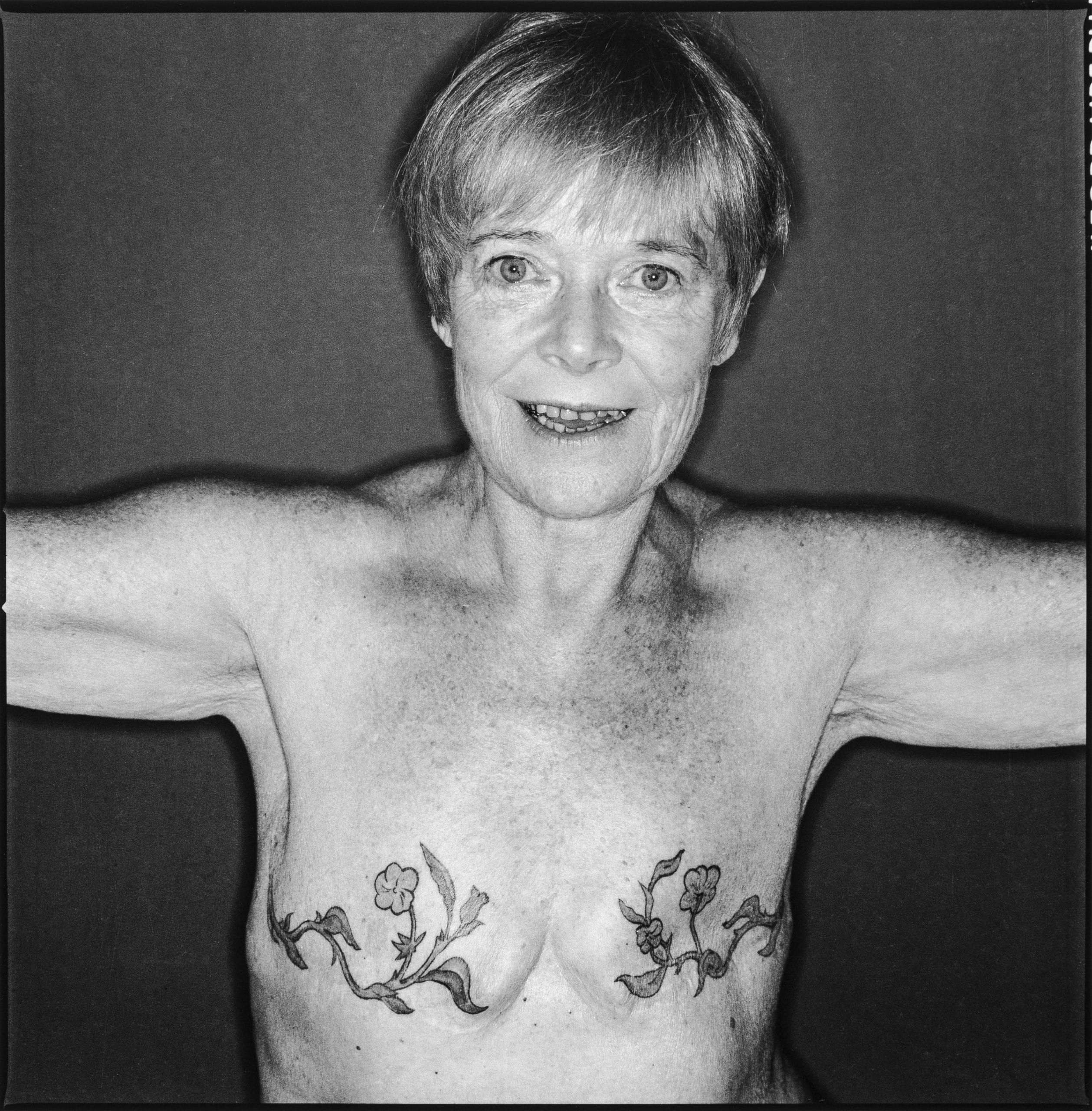

The stick fell down. Volker stood it up again before pressing the shutter button, the stick now several metres away from the erect, great old lady, but still in the frame. A classic Hinz mix of respect for an icon and the desire to let the photograph give a disrespectful answer.”

If, as Hinz says, “an image is a piece of art if it tells the viewers something about the person he is picturing”, then it’s fair to say his images say as much about him as an image-maker as they do about his subjects.

In Love With Photography by Volker Hinz, foreword by GEO editor-in-chief Peter-Matthias Gaede, is published by Edition Lammerhuber.

It is available in limited-edition, signed and numbered copies here.