Three years ago, Lorenza Bravetta, director of Magnum Photos in Paris, started to feel “a strong need to come back to Italy.”

After living abroad for 17 years, she decided she wanted to return home to Turin, Italy, and create a “lasting and dramatic” photography institution.

After a lot of work, her idea has been realised to remarkable effect. She is now the director of Camera, the Centro Italiano per la Fotografia; a specialist photography gallery in the heart of the city which boasts 2000 square meters of floor space.

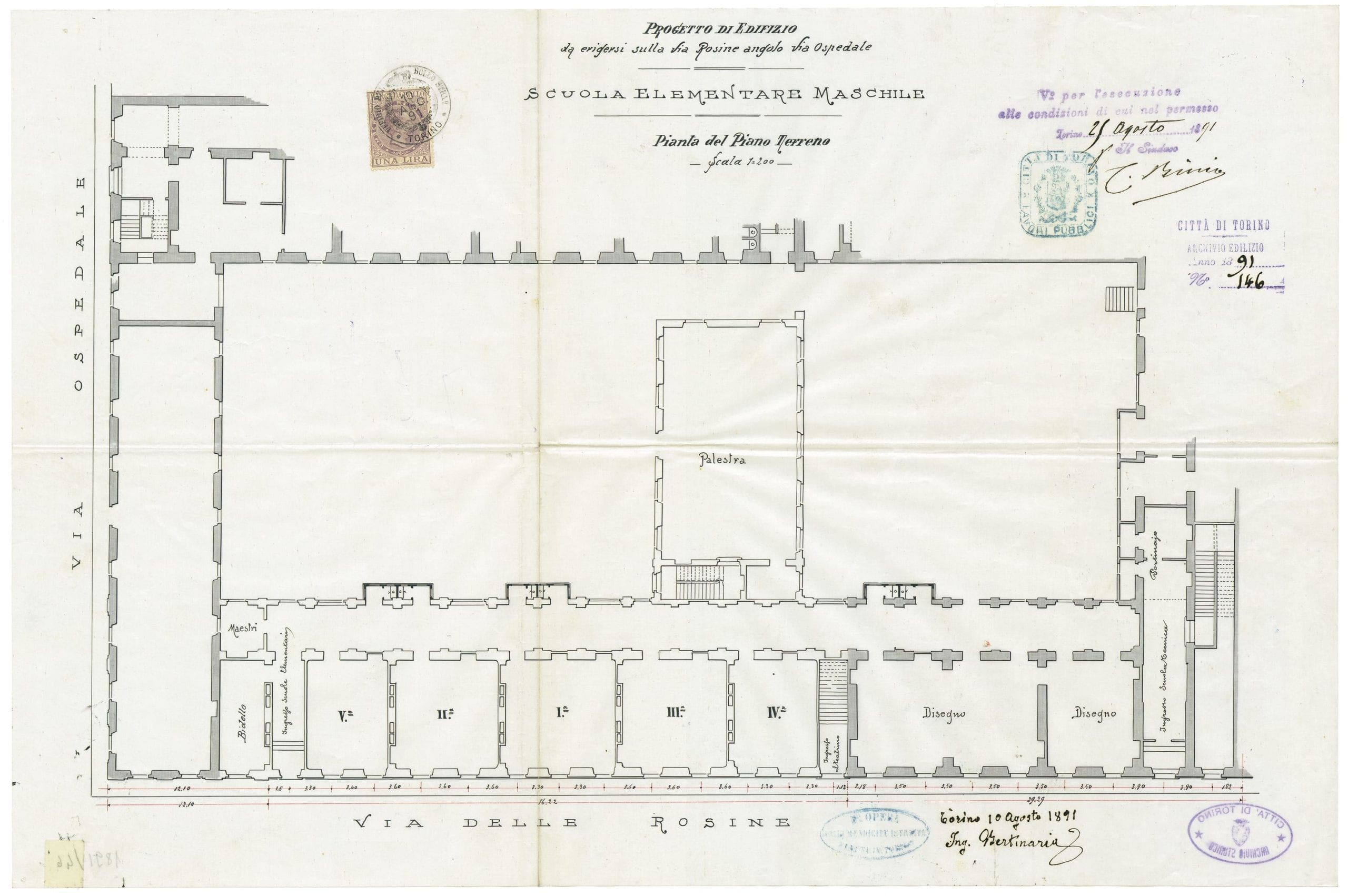

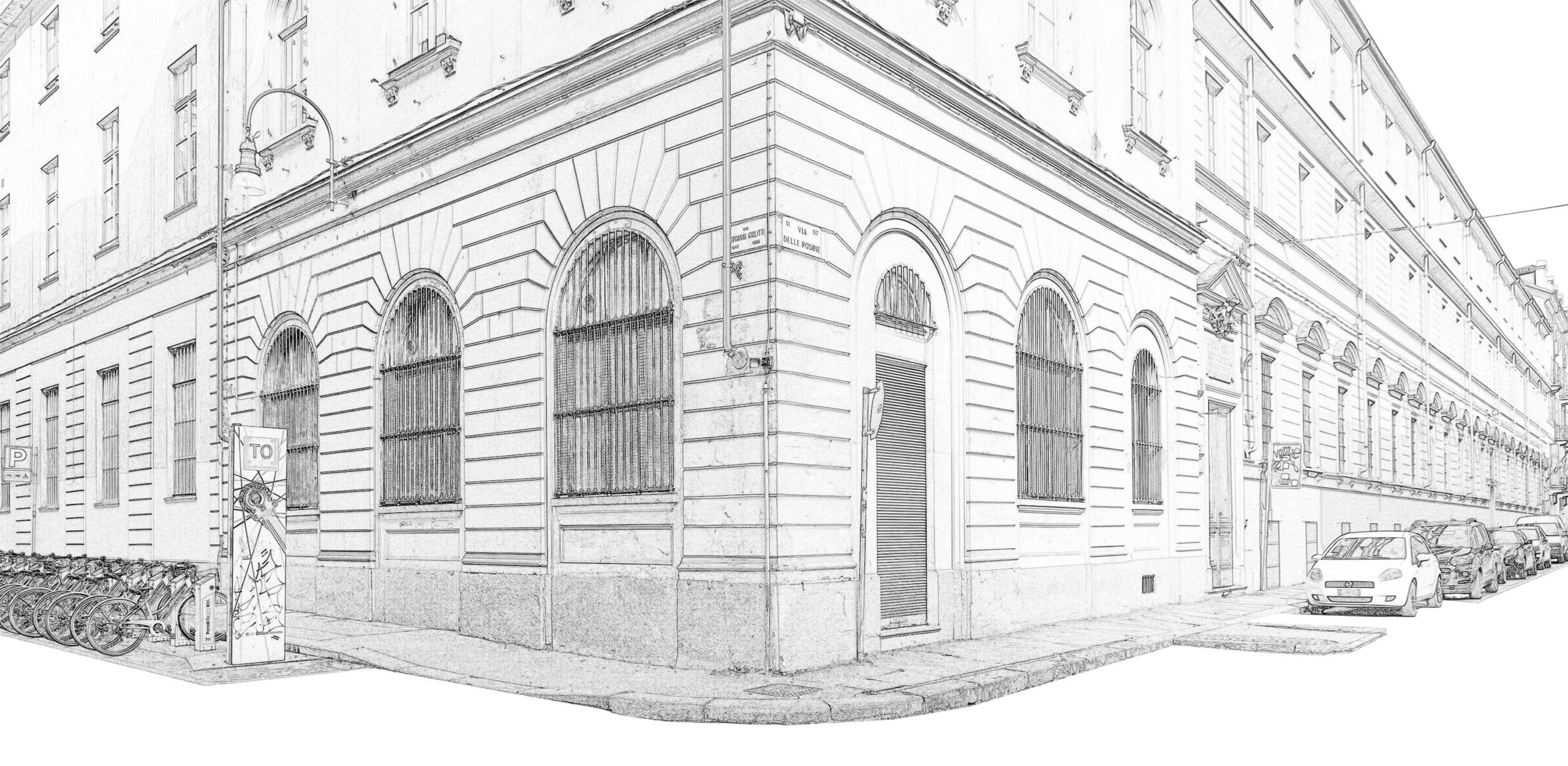

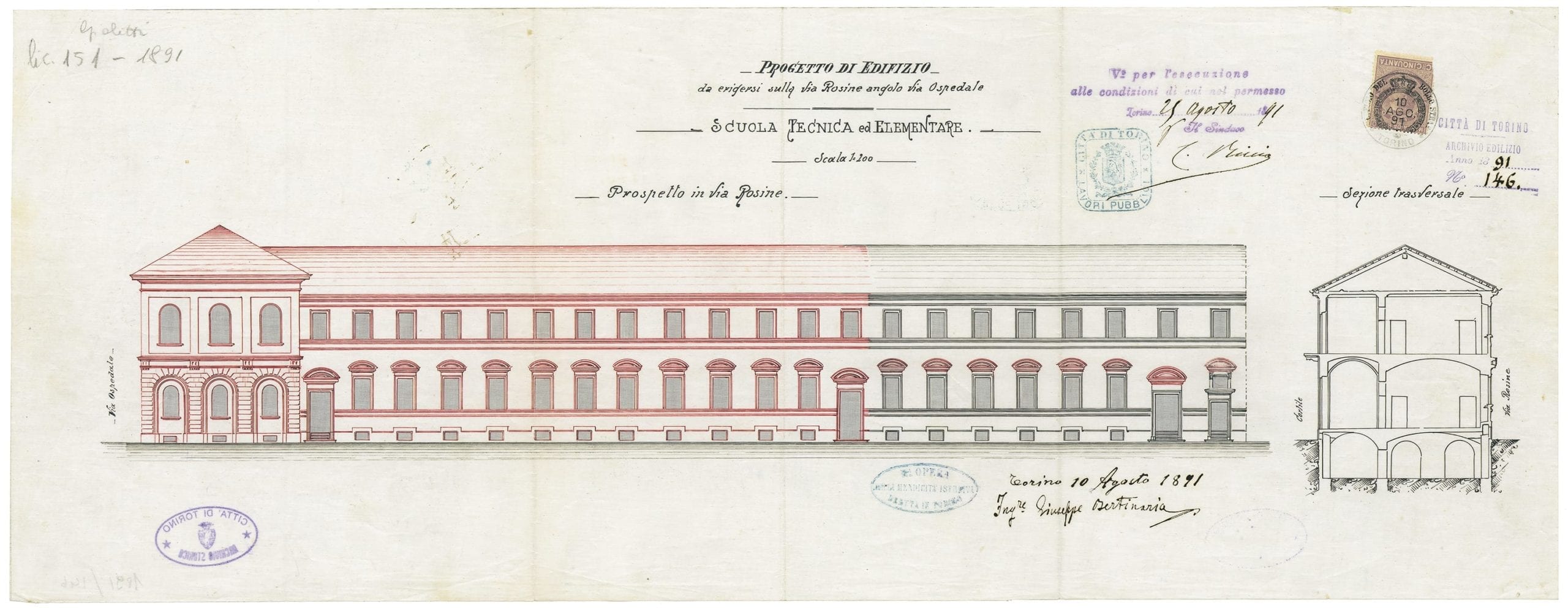

Based at number 18 Via delle Rosine, in premises leased from the local Opera Munifica Istruzione (an Institution of Public Aid and Charity) known as the Isolato di Santa Pelagia, Camera has repurposed a 19th century building where the very first public school of the Kingdom of Italy was founded. “Architect Benedetto Camerana has entirely renovated the space for us, but the original structure is still vey much visible, with a corridor around 70m long constituting its backbone,” says Francesco Zanot, Camera’s chief curator, who has been working on the project for the last two years.

“So it is a very challenging space, combining the intensity of history with all the requirements necessary for a modern museum. It will be interesting to see the mutual dialogue between the building and the photography included in our exhibitions.”

Camera, which includes a school of photography and an archive of Italian photographic history, is built on a shared vision, “to investigate photography both as an artform and as a social-political tool; to explore photography’s relationships to other media and disciplines, to act as an observatory on the latest uses and abuses of photography, and to share our vision with the broadest possible public,” Zanot says.

As such, Bravetta and Zanot have developed an ambitious programme of exhibitions. Eight shows will be staged per year, comprising of three main exhibitions and five supplementary events. Italian works will alternate with international shows, but each exhibition will aim to investigate “the various relationships between photography and other media, aiming to activate a dialogue with other contexts,” Zanot says, adding that: “We are interested in going deeper into the links between photography and politics, technology, economics and social media.”

Camera’s first exhibition, which opened on 01 October, is a case in point – an extensive retrospective of Boris Mikhailov’s work. Mikhailov, a former engineer in the-then Russian city of Kharkiv, was blacklisted by Russian authorities after the KBG discovered naked pictures of his wife and accused him of distributing pornography. Working hand-to-mouth in a series of unofficial jobs, th Ukranian continued to compulsively photograph, creating a decades-long chronicle of the region before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The artist has “recounted, described and deformed” the arc of history, says Zanot, and the forthcoming show will focus on his use of media, his ability “to use print cut-outs to painted photographs, the way he couples photography with writing, his use of staged images contrasting with the most hardline documentary style”.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a photobook, housed in the final room of the exhibition space, and co-edited by Camera and the Cologne-based publisher Walther König, which includes over 500 photographs collected by Mikhailov over the course of his career.

From there Camera will explore Italy’s own complex history, with the exhibition Italia 1968–78 which opens in January 2016. It investigates “one of the most complex and delicate periods of Italian history”, the so-called ‘Years of Lead’, which saw a series of terrorist attacks for which no-one was prosecuted – and which severely disrupted the country’s political establishment for decades. The exhibition will explore “photography’s role as an instrument for social and historical investigation” during the era, combining photojournalists’ images with eyewitness photographs, from the imagery of official media to the private productions of militant groups, to the works of self-defined artists of the time.

The show will be curated by a host of different experts, including BJP’s Photocaptionist author Federica Chiocchetti and her co-curator Roger Hargreaves who, working with the Archive of Modern Conflict, created the award-winning Amore E Piombo in 2014. The exhibition, Zanot says: “Gives us the possibility to state that, since the very beginning, photography is everywhere around us. Its viral nature was a key element of the Years of Lead, and is one of the main issues as we will look into in the future.”

Other shows in the pipeline are exhibitions dedicated to Stephen Shore, Erik Kessels, Vincenzo Castella, Gerard Fieret, Valerio Spada and Francesco Jodice; but if the exhibition programme is impressive, it’s only part of Zanot and Bravetta’s offering. Just as significant is the archive of Italian photography it will house, collated both from private and public collections. Italian historians are helping the gallery with “the reordering, cataloguing, meta-dating of imagery”, Zanot says, with the aim of creating exhibitions that explore Italian culture through such archival and found imagery. “The long-term objective of the project is to build a platform which will allow researchers, cultural operators and the public to access the visual contents of Italian photographic collections through a shared digital system,” Zanot says.

The archive will also play a key part in Camera’s educational programme, which includes workshops, seminars, master classes and educational partnerships with local schools, each designed to complement the ongoing exhibition programme and development of the archive as a public resource. “We want to involve those sections of the population that, for social reasons, do not usually visit art exhibitions and events, so we are thinking to different strategies to open to them without only waiting for them to fall into our space,” Zanot says.

Camera is a private project, made possible by funding from two institutional partners – the Italian banking group Intesa Sanpaolo and ENI, the Italian multinational oil and gas company headquartered in Rome. Leica, the camera manufacturer, and Lavazza, the Italian coffee company, have also agreed to partner and provide sponsorship for the gallery launch. “You need to find the perfect balance,” Zanot says of the gallery’s funding. “We would like to be totally independent and develop our vision, but at the same time we know that we will always need to find somebody who shares our ideas and helps us to make them real.”

Find more information here.