Shortly before I’m due to conduct a long-distance telephone interview from Manchester to the Los Angeles Police Museum, with the self-proclaimed Demon Dog of crime fiction James Ellroy and his temporary collaborator Glynn Martin (executive director of the museum), I open an email from a mate with an attachment to Werner Herzog’s 5 Favourite Films. Above the list there is a quote from Herzog himself that stands out like a bruise on a child: “I believe the common denominator of the universe is not harmony, but chaos, hostility and murder.”

I make an instant note of it, but my 30 minutes are up before I can ask Ellroy if this is how he sees the universe. I’m guessing it is: his body – or his cadaver – of work is the written equivalent of a dumping ground. Murder – including the unsolved murder of his own mother in 1958 – corruption, tortured cops, bent authorities, flawed femme fatales: these are his obsessions (he is a chronic obsessive on and off the page). But then Ellroy is a professional performer (again, both on and off the page): a slick self-dramatiser from the ‘Hollyweird’ (his phrasing) school of acting, who wisely opts to maintain his own myth over and above candour, so his seemingly straight answers may not be as straight as they first seem.

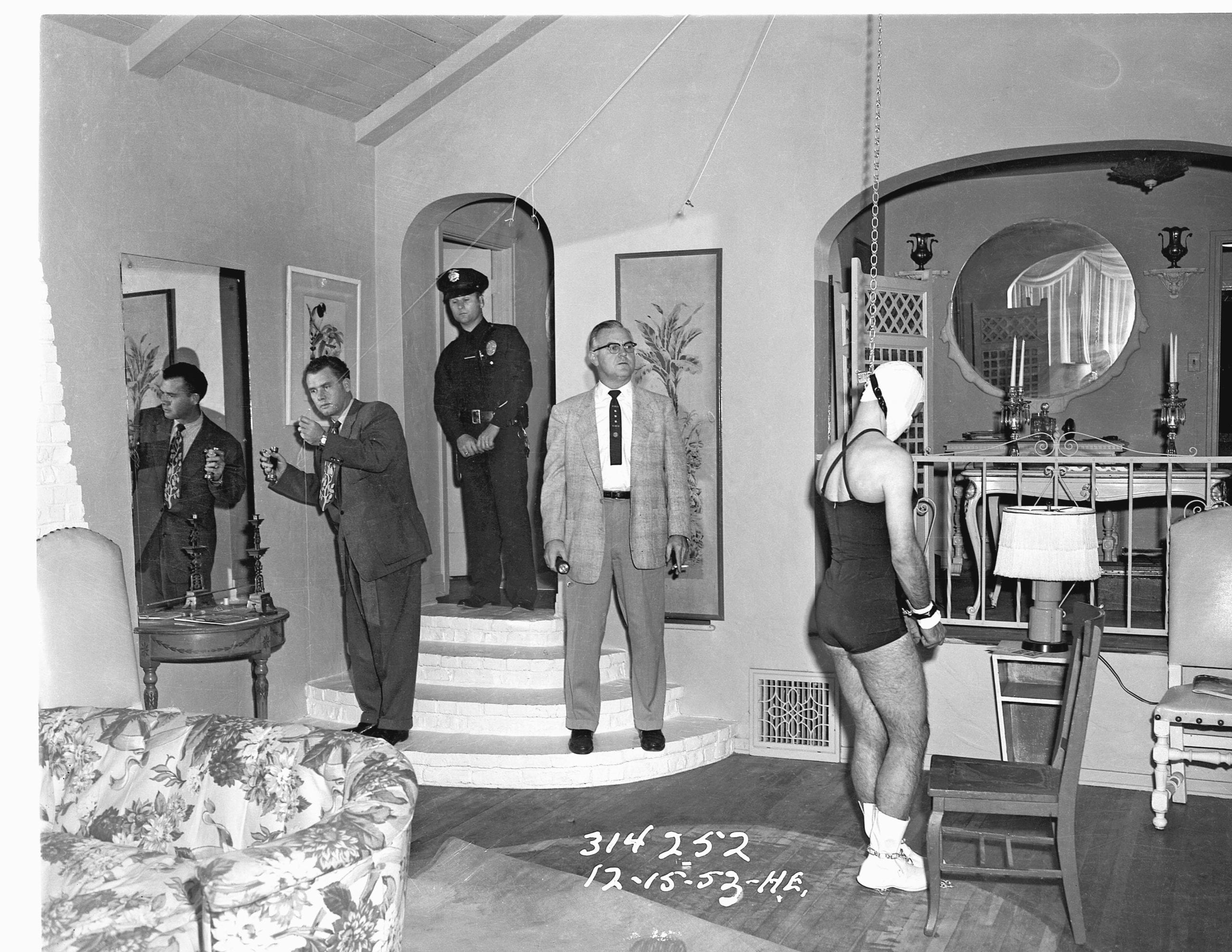

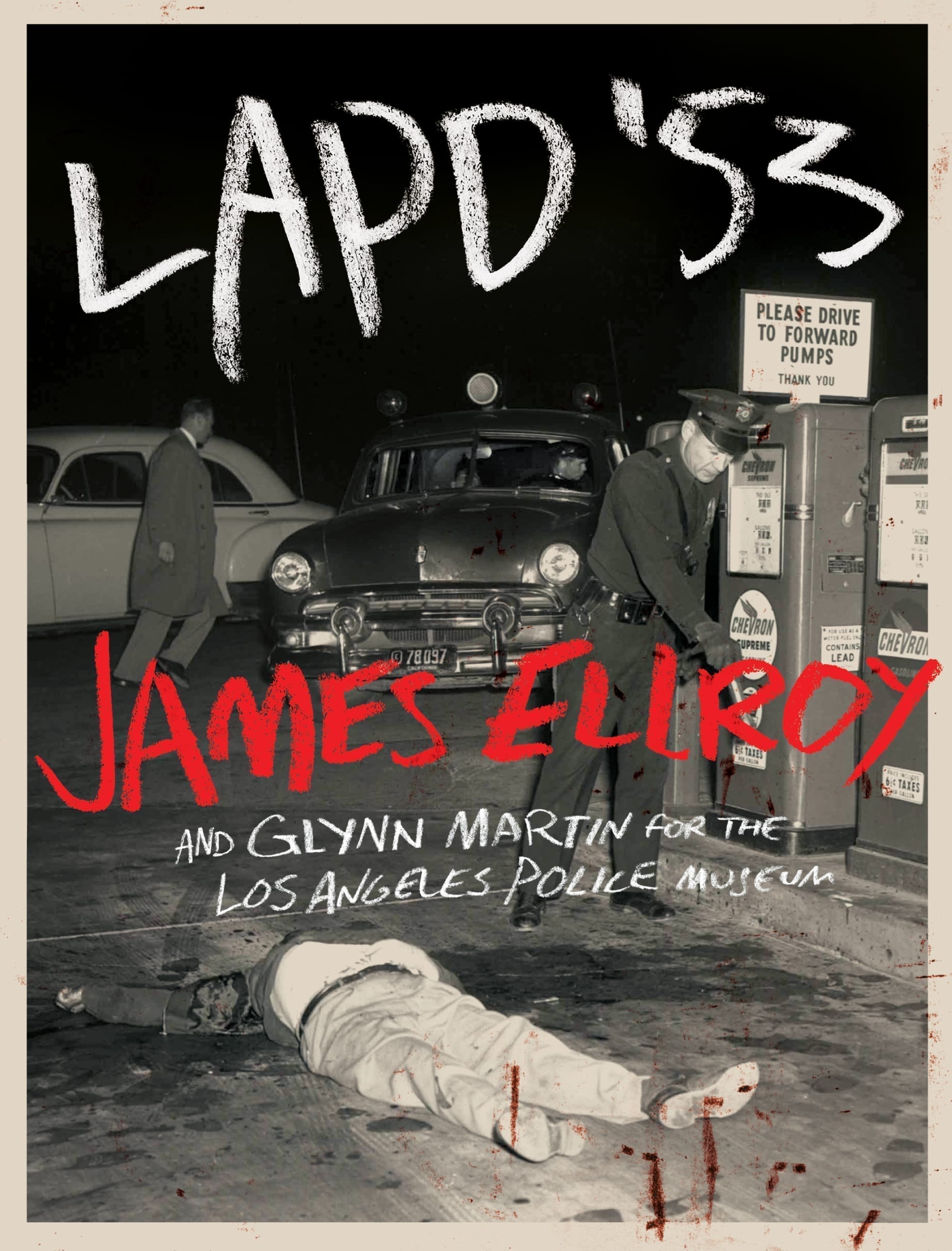

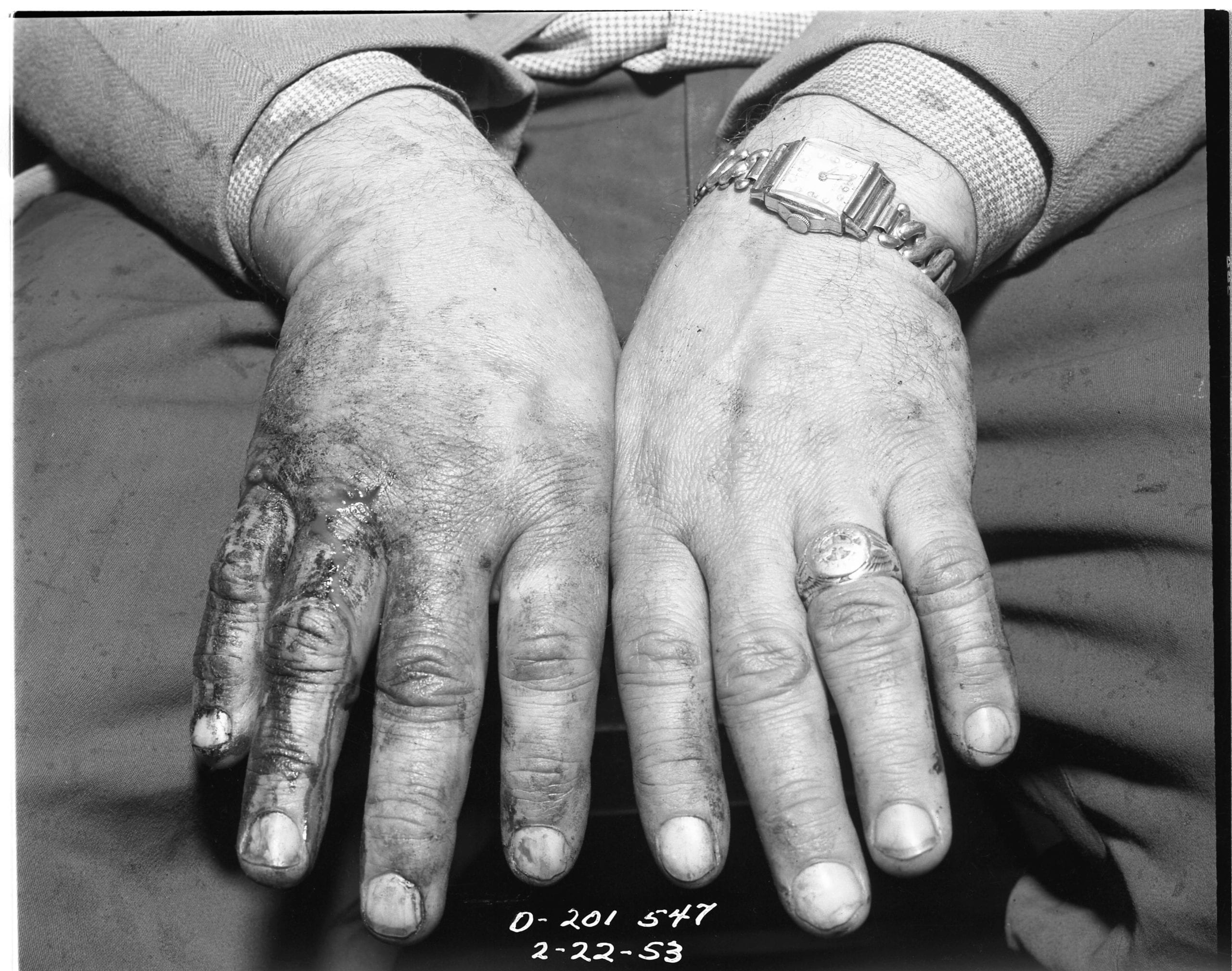

His latest book, LAPD ’53, is an absurdly comic and hypnotic display of magical memory that is neither history as fiction nor history as non-fiction but something altogether different and more aggressively poetic. Aided by Martin, who served on the LAPD from 1982 to 2002, he has meticulously sifted through the Los Angeles Police Museum archive and curated a selection of powerful crime-scene photographs taken throughout the City of (fallen and bloody) Angels in 1953. The themes are familiar: murder, manslaughter, suicide and home invasions. The format is less familiar.

“Every photograph I looked at provided me with a visual narrative,” he says. “I’m a basic narrative writer. I describe the thing as it is. I believe I am always right on my judgement with crime. Make sure you are right, then go ahead. I always make sure I’m right – usually far-right.”

“James has been a great part of the museum for a long time,” says Martin. “We understand his literary style and his art. LA Confidential and his most recent novel Perfidia – they’re absolute masterpieces. We are nothing but proud of working with him.”

Alongside each severe black-and-white still, he purposefully and playfully muddies the already murky waters of crime nostalgia by writing himself into the narrative as a dope-fiend, slang-talking, Lenny Bruce-befriending, Charlie Parker-watching perverted five-year-old boy (he was born in 1948 so the chronology is true at least) complete with his “voyeur’s cap on”.

Here’s an example (emphasis his own): “Dig this, fuckers – I’ve personally observed every crime scene depicted in this book. I was there when those flaming flash bulbs popped. That’s why my coruscating opinions carry so much weight… my superpowers have metamorphosed into magical memory.”

Not for the first time, the tabloid-like alliteration and manically self-centred nature of these extended and sometimes inflammatory captions has obviously divided opinion. The New Statesman praised the unarguable beauty of the book but questioned his hyperactive line in “reactionary nostalgia”, as he calls it, writing: “…[he] never seems overly concerned with penetrating to the human heart of the crimes.” To the detractors, he takes way too much pleasure in documenting the carnage.

“This is the first time I’m a baby-crime lord and a dope fiend at the age of five,” he tells me. “There are two ways of looking at it: maybe I have a very good memory, or maybe I made it all up. This is how it was: look at the photographs and come up with some high-flying shit that sounded good. Glenn wrote his introduction. I wrote my introduction. It’s been kicking around in my head for a while. I decided very early on that we should have fun with this book, that we should celebrate the language of the time, celebrate the police work of the time, the policemen of the time, and demonise the criminals of the time. This is a potpourri of crime. It’s pathetic, it’s transgressive, it’s vile, it’s human.”

“The concept belongs to James,” Martin adds. “He’s the master of this. He didn’t want to make a book of splatter shots. He wanted to accentuate the artistry of the photographs that were taken by regular flat-footed policemen and not skilled photographers. The photographs are all about putting the bad guy in jail and arriving at justice for the victim of the crime. These officers were professionals, and I think many of them took the most direct photograph possible. It turns out that that’s the best. These would have been tenured officers who no doubt saw bad things often.”

The general idea behind LAPD ’53 is commercial. Ellroy and Martin hope to make enough money off the back of it to publish their own museum books in the future. In this context, Ellroy’s showboating may well have hit its mark as it was an instant bestseller in America.

“The chances are excellent for producing a sequel,” says Ellroy. “There will be a lot of pimp shit in it, death shit, racial shit, kid shit. I don’t know from which decade. We need an offer first.”

In many ways Ellroy is a museum piece himself. Throughout the book he repeatedly compares the LA of NOW to the LA of THEN, with all the subtlety of capitals themselves. He is not impressed. “I think everybody’s fucked up on the internet,” he says. “I think the world is a strange motherfucking place. LA is too explicit, too many people, too many cars. There’s a giant safe sex billboard a couple of blocks from where I live with a picture of a condom and the words, ‘Why Worry?’ emblasoned on it. That’s too explicit for me.”

Getting him to elaborate a little more on why modern LA doesn’t match up to THEN, I try to steer the conversation away from his pet subject – the past – by asking him about images of contemporary race-related American police violence that have recently spread across the internet and the news, and also the moral vacancy and abject humanity of modern TV news itself and how this may reflect and/or affect Obama’s legacy. The question wasn’t written in such a long-winded style, but as soon I broached the subject I sensed tense aloofness down the phone and was seized with an air-filling compulsion to ramble.

“It is not my job to comment,” he says. “I was five years old in 1953. Obama was minus eight. I live in my imagination. My imagination is richly, equally, voluntarily destroyable. As far as I’m concerned, I’m writing the second book in my [second] LA Quartet [the first published between 1987 and 1992]. In my mind it’s the winter of ’42 now.”

“You’re talking to the wrong guy about this,” interjects Martin. “James has neither a television nor a computer.”

“I owned a TV once,” Ellroy says. “It was black-and-white. Just black people and white. That was in the 1960s.”

A standout paragraph in the book takes an equally dismissive line on the over-analysis of the cinematic genre he’s mostly closely associated with, as a crime writer who has had several of his books adapted for the screen. “The great theme of film noir is, ‘You’re fucked’.” But as always with Ellroy, wry wisdom undercuts the petulance: “Were the police photographs collected in this book suggested by the film noir style, or was film noir a stylistic offshoot of cop pics? Crime Wave [directed by Andre De Toth] suggests a reciprocal synchronicity. It was shot in ’52 and released in ’54. It’s got that transitional look that so informs LAPD ’53.”

The obvious and major difference here is that Crime Wave (a film he lovingly describes at length), and all film noir for that matter, were never as explicit (that word again) as the images in the book are, nor as kinky or crazed or mundanely horrific. How could they be? For in these times of NOW there are fewer censors. The book is the real deal, the elephant in the living room, the skeleton in the cupboard, the black sheep of the family, the you-name-it, caught on camera.

The apparent sincerity of their endeavour and the mutual appreciation between Ellroy and Martin is also honest and captivating. They share common crime ground, and like any classic TV or film cop partnership, they are opposites of a certain degree, who work well together and riff off each other, seemingly because they are too long in the tooth to try to change one another and let each other do and say what they want. Ellroy knows the publicity game inside out. Interviews bring the best and worst out of him. Thus, he can – and does – play up to it with demonic zeal. Martin is new to the game and is understandably more reticent and exact. But both are deeply passionate about their chosen subject, the brute glamour of the LAPD, THEN.

This passion is at its most heartfelt in the profile pictures that close the book out like the end credits of a film: Hansen, ‘Mr Homicide’, LAPD’s lead investigator on the most celebrated unsolved murder case in American History – The Black Dahlia; Thad Brown, Chief of Detectives, a ‘great detective’; ‘The Hat Squad’, four strapping 6’ 2” plus (the set height requirement for the job) white fedora-wearing (straw for warm weather, felt for winter days) cops who targeted men with guns and pulled some wild-and-wooly shit. The proud and protective tone of Ellroy’s prose as he describes these stern authoritarians is similar to hearing a mother extolling her children’s very best qualities to an attentive stranger at the bus stop.

“I love those photographs. I love The Hat Squad. I love Deputy Chief Thad Brown. It was like ending the book on a series of honorariums.”

For all the contentious buttons that Ellroy delights in pushing, including the cult of the modern hipster – “I love hipsters when they buy the book,” he tells me. When I ask him the definition of the word, he doesn’t miss a beat: “The men need to shave and the women need to bathe. They are by and large rock ’n’ roll shitheads who haven’t figured out that rock ’n’ roll is kids’ shit they haven’t grown out of. They are more or less like everyone in Great Britain. It’s kids’ shit. It’s nothing.”

For all his mischievous bluster and thunderous insecurities, he makes it clear to me that “there is always hope and heroism in my books” and that he does not deal in “nihilism”.

“I am actually a very nice guy unless you pull the Demon Dogs’ tail or pat him the wrong way,” he says.

The glaring contradiction at the heart of his dislike of NOW is that he needs the benefits of its in-built perks – hindsight and perspective – in order to write about THEN, in his distinctively modern style. Yet the saddest aspect of LAPD ’53, among many other sad aspects, is that the argument between THEN and NOW is little more than a dinner-party, pub or office tiff when confronted with the timelessly gruesome image of a corpse lay cruciform next to an oil pump at a gas station. An image like that could be from any age. Death, destruction and wasted bodies: these horrors are beyond anybody’s clock.

LAPD ’53, by James Ellroy and Glynn Martin for the Los Angeles Police Museum, is available from IndieBound and most online booksellers.