It is a cool midsummer’s evening in Mayfair’s Cork Street – the nucleus of London’s contemporary art world. Number 33 is the professional home of Prahlad Bubbar – collector of Indian and Islamic art – and the location of his new exhibition, The New Medium: Photography in India 1855-1930.

The New Medium is a neat survey of the birth and rise of photography as a major art form in the subcontinent. Twenty-five photographs are ordered chronologically around the bright, airy rooms of the gallery, each one chosen to reflect a distinct decisive moment in Indian photographic history.

Driven by Bubbar’s background in art history, his recognition of context binds the project together as the beginnings of a technological and artistic revolution in the context of one distinct and, in itself, rapidly evolving culture.

In the middle of the 19th century, photography took over from painting as the new mode of representing the world – hence the name, The New Medium.

The exhibition frames an era in which the diverse customs of India – the temples, animals and people – could all be experienced with objective photographic clarity for the very first time, above and beyond the limits of any painter’s eye.

The exhibition begins with landscape shots of famous architecture – the Taj Mahal, Golden Temple, et al – commissioned by the East India Company when the camera first arrived on Indian shores in the mid-nineteenth century. In one image, taken by John Murray after the Indian rebellion in 1857, a pyramid of cannonballs are piled high in front of the Pearl mosque in Agra, reflecting a period of reinvigorated British colonial dominance.

As the practice of photography evolved, a contrasting style developed alongside the predominantly European influence on the art form. This turn is most notable in the work of Raja Deen Dayal, India’s most celebrated 19th-century photographer, whose appointment as court photographer to the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad allowed him unique access to the inner circles of aristocratic life.

“British photographers had preconceived ideas about what constituted a beautiful landscape or portrait,” Bubbar tells BJP. “But Dayal didn’t have the same conditioning. This made his work distinct. He was the pre-eminent Indian photographer.”

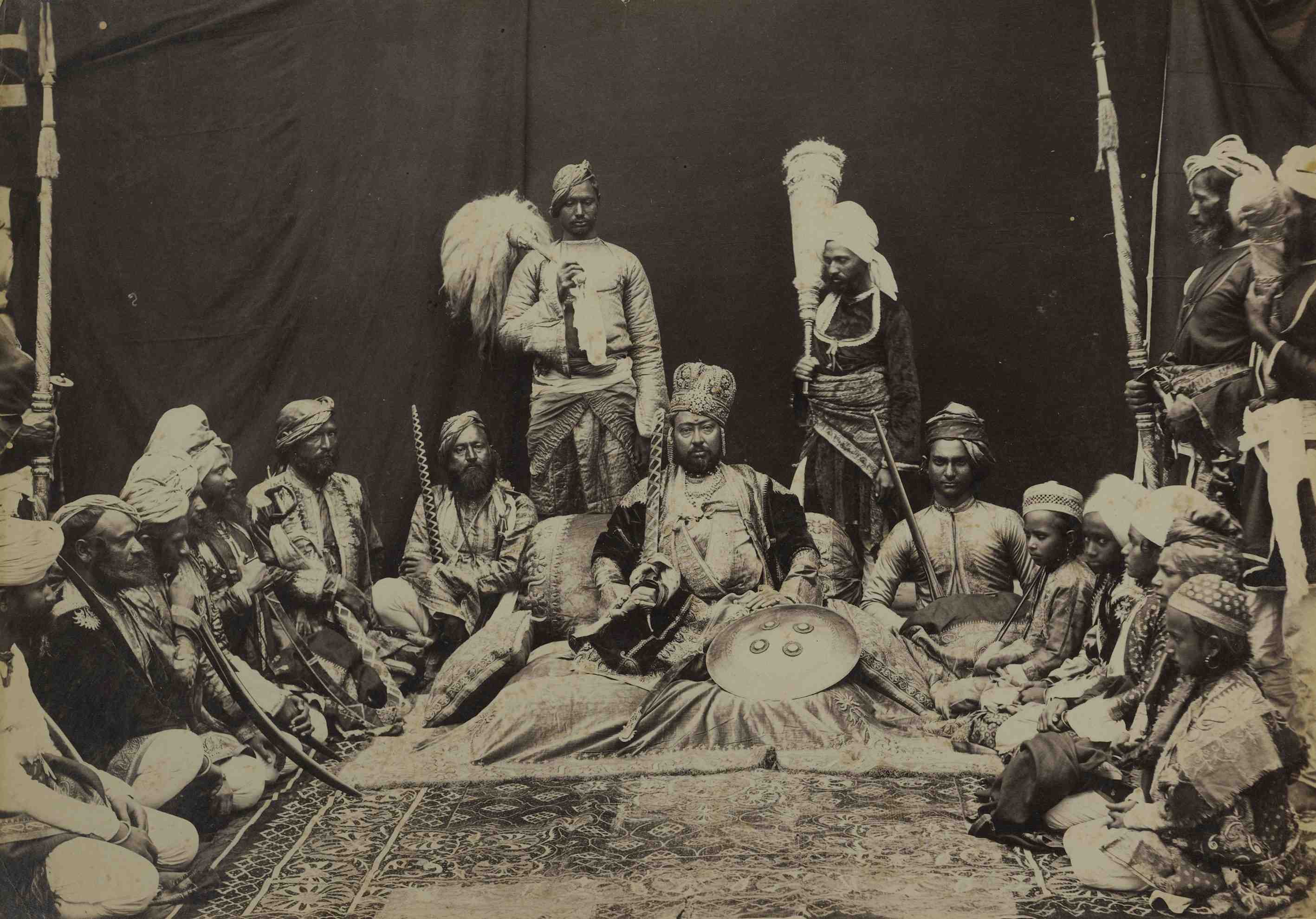

One of Dayal’s portraits, taken in 1882, depicts the Maharaja of Bijawar sitting cross-legged, surrounded by servants. This moment – what Bubbar calls “the great encounter” – that would have had unprecedented significance for its subjects, for they are traditional leaders from remote parts of India, facing the long exposure of an original camera for the first time in their lives.

Juxtaposing these portraits with more modern equivalents is a core achievement of The New Medium. After the turn of the 20th century, an increasingly commercial demand for portrait photography led to the opening of studios in major Indian cities. This translated into different stylistic conventions, such as the use of elaborate, Victorian-style indoor props – ornate wooden stools, painted curtain drapes – in an attempt to emulate a European environment.

The biggest contrast to Dayal’s early portraits is Bubbar’s favourite image of the collection: American photographer Man Ray’s intimate photograph of Maharaja Holkar of Indore, dressed in a suit and tie, circa 1930. He says: “Holkar was ahead of the game; a truly 20th century guy. He wanted to create his entire own modern identity, so he surrounded himself with all the newest things and finest people.”

The globalising, empire-driven nature of the early 20th century meant the shift towards photography was taking place all over the world. Initially, many of the prints in Asia would have taken months and travelled many thousands of miles to be developed. But regardless, India’s internal market had its very own nature. “These wealthy maharajas dotted across the country were consumers; they wanted the techy stuff, too – not just art and jewels, but cameras and bicycles,” Bubbar says.

Perhaps this trend of technological consumption is what eventually evolved into one aspect of the India we see today: a ballooning supereconomy and an empowered middle class.

But, coming from a perspective framed by digital imagery in 2015, The New Medium’s rearview investigation shines a light on how much the trends of photography have evolved since the still camera took over. What will be the 21st century’s ‘new medium’ be?

Stay up to date with stories such as this, delivered to your inbox every Friday.