“We’ve had five great extinctions,” says Edward Burtynsky. “Now our species is having a similar…

“We’ve had five great extinctions,” says Edward Burtynsky. “Now our species is having a similar…

Alighting at Peckham Rye train station in south London, a short walk across a busy market street takes you to the Bussey Building complex, a former cricket-bat factory that is now home to an assortment of bars, music venues, yoga studios and art spaces, including the Copeland Gallery. This bright exhibition space is once again the main site of Peckham 24 festival of contemporary photography, celebrating its third edition this year and running over the weekend of 18 to 20 May to coincide with Photo London – more than the 24 hours with which it launched and gave it its name. “Last year we were literally pushing people out of the door at midnight,” laugh the co-founders, Vivienne Gamble, whose Seen Fifteen gallery is in a nearby space, and artist Jo Dennis.

“This isn’t something new or something connected to a particular part of the country,” says Sarker Protick, speaking about his recent work, Of River and Lost Lands, which deals with the contemporary relationship between people and nature in Bangladesh, in the context of the devastating damage and loss of land caused each year during monsoon season. “The seasonal rising and falling of the many rivers in our country is part of our culture. It’s the first thing we learn at school; we are a country of rivers. Music, poetry, philosophy, folklore, religion – all have key elements connected to the river.” Protick’s photographs, on show at Hamburg Triennial of Photography as part of Enter, curated by Emma Bowkett and Krzysztof Candrowicz, were all made along the powerful Padma River. “When the famous Ganges flows over the border from India into Bangladesh, it becomes the Padma; a river that many along its banks depend on for their livelihood, but paradoxically the river is also the main cause of destruction.”

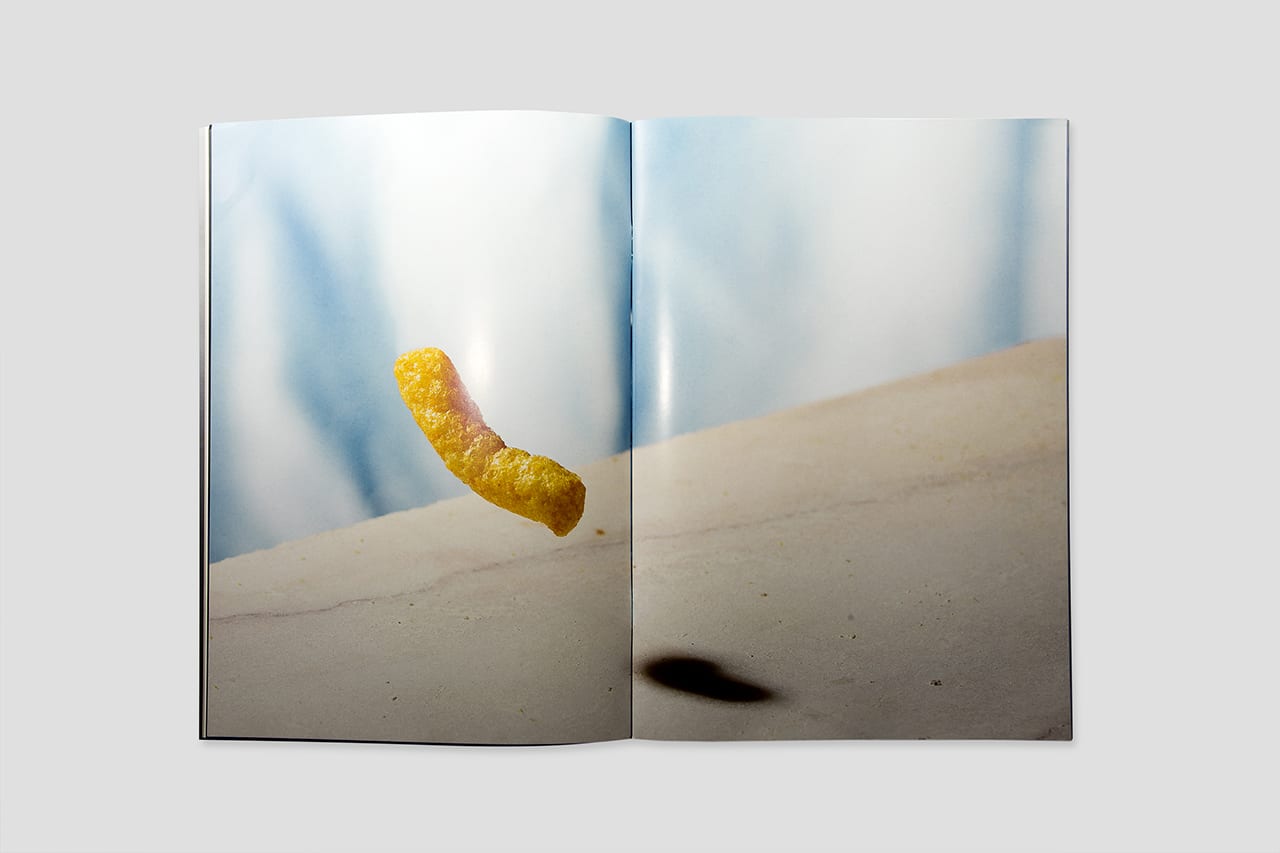

“People always try to find the most incredible thing, it’s always about perfection and the extraordinary,” says Max Siedentopf, co-founder of Ordinary magazine, “but there are so many things around us that we’re not aware of, all these mundane boring objects that we don’t even notice.” This is the philosophy behind Ordinary, brainchild of Siedentopf and designer Yuki Kappes, which has returned to print after a year’s hiatus. Each issue, the magazine asks 20 photographers to reimagine an ordinary object – be it a kitchen sponge, plastic cutlery or a single white sock – as something extraordinary. The object featured in each issue is gifted to the reader as an “extra” in a plastic bag on the front cover. This time though, the bag arrived empty.

Rubber Factory is a contemporary art gallery on New York’s Lower East Side, focusing on…

“One could easily say there’s nothing to photograph there, because it’s just like any other park,” says Latvian photographer Arnis Balcus of Victory Park. Situated in the Latvian capital Riga, Victory Park [‘Uzvaras Park’ in Latvian] was officially opened in 1910, in the presence of Tsar Nicholas II and the Mayor of Riga. But, as Balcus explains, “it is a park with a complex history”. First built to commemorate Latvian independence, the park was given its current name after the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany in WWII, and as such “embodies the historical trauma of a small Baltic nation”, says Balcus. It’s famous for its Victory Monument which, at 79m high, looms over Riga’s skyline and provides a daily reminder of the controversial issue it signifies.

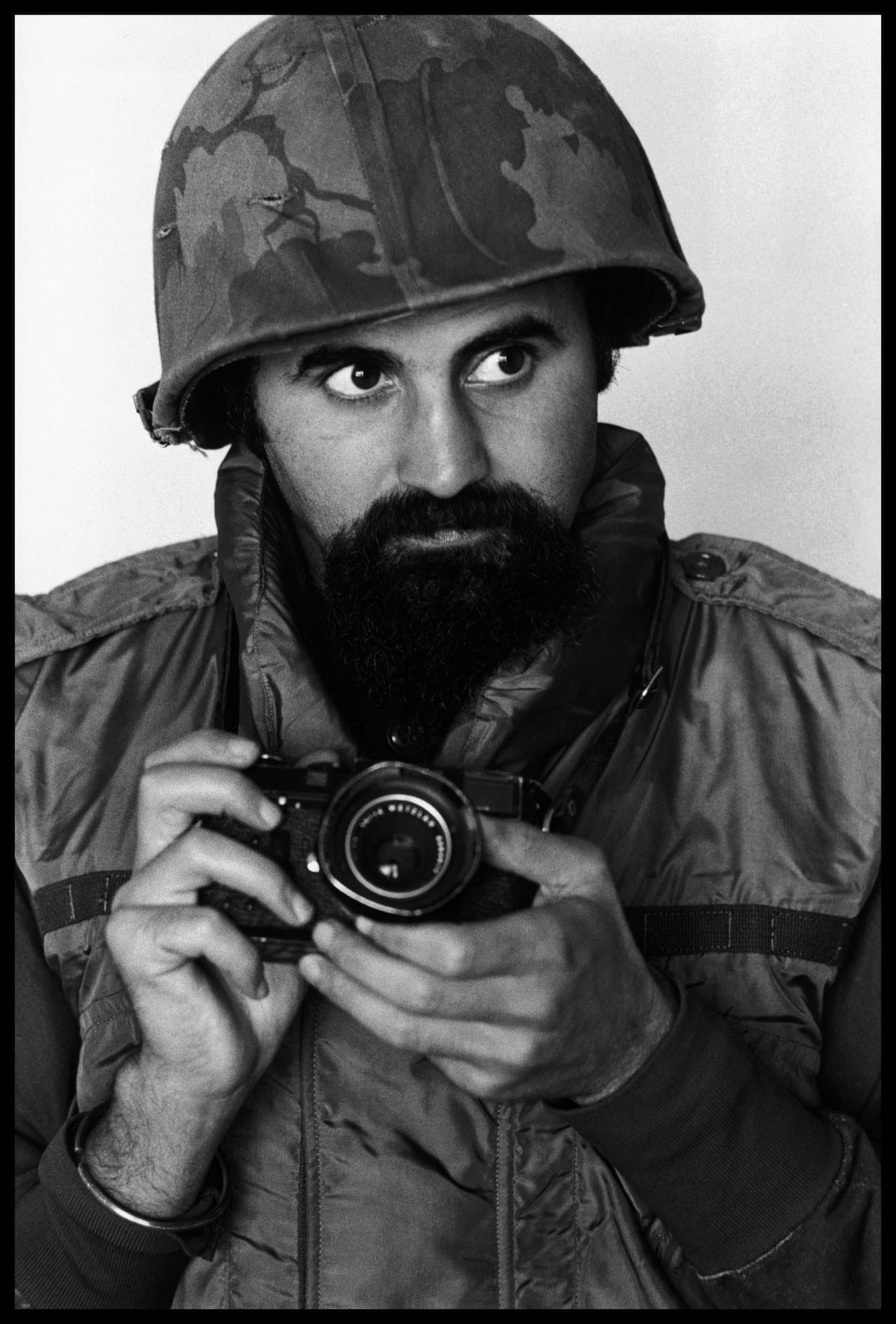

“I used to describe myself as a photojournalist, and was very proud of it,” wrote Abbas in 2017. “The choice was to think of oneself either as a photojournalist or an artist. It wasn’t out of humility that I called myself a photojournalist, but arrogance. I thought photojournalism was superior, but these days I don’t call myself a photojournalist because, although I use the techniques of a photojournalist and get published in magazines and newspapers, I am working at things in depth and over long periods of time. I don’t just make stories about what’s happening. I’m making stories about my way of seeing what’s happening.” Abbas has been described as a “born photographer”, who over his 60-year career covered war and revolution in Vietnam, the Middle East, Bangladesh, Biafra, Chile, Cuba, Apartheid South Africa, and Northern Ireland. He also pursued a lifelong interest in religion in his work, shooting in 29 countries to create the book and exhibition Allah O Akbar: A Journey Through Militant Islam, and publishing long-term series on Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, and animism.

Running since 2013, the PHM Grant has a reputation for finding interesting new photographers such as Max Pinckers, Tomas van Houtryve, and Salvatore Vitale. Now the 35-strong shortlist for the 2018 has been announced, with the winners due to be announced on 08 May and four prizes up for grabs – a first, second and third in the main award, plus a New Generation Prize. Each winner gets a cash prize plus a publication on World Press Photo’s Witness, a projection at Cortona On The Move and at Just Another Photo Festival, and promotion via PHmuseum. The jury handing out the awards is made up of photography specialists – Genevieve Fussell, senior photo editor at The New Yorker; Roger Ballen, photographer and artist; Emilia Van Lynden, artistic director of Unseen; and Monica Allende, independent photo editor and cultural producer. The jury is able to give Honourable Mentions, up to six in the main prize, and up to three in the New Generation Prize.

With its dungeon-like chambers, ghostly corridors, and casemates on which guns would have stood, Coalhouse Fort in East Tilbury, Essex, is an unlikely art gallery. But on 28 April 2018, the 144 year fort on the edge of the Thames Estuary will open its doors to the public for a pop-up exhibition, featuring artists such as Felicity Hammond, Dafna Talmor, and Corinne Silva. Caught between a military past and its current use as a tourist attraction, the fort’s identity is shifting. The building is deteriorating and being reclaimed by nature – the antithesis to its original role as a robust military base. A team of volunteers is working with the local council to restore it, and keep it from falling into obscurity. But while it may be ramshackle, it is a space full of artistic possibility, and that is what captured my imagination when I was invited by artist and lecturer Michael Whelan to curate a pop-up exhibition there. Whelan had been working with Thurrock Council to digitise its rich archive of photographs, documents, and military-related artefacts and, noticing the site’s potential as a space to show art, decided to put on an exhibition.

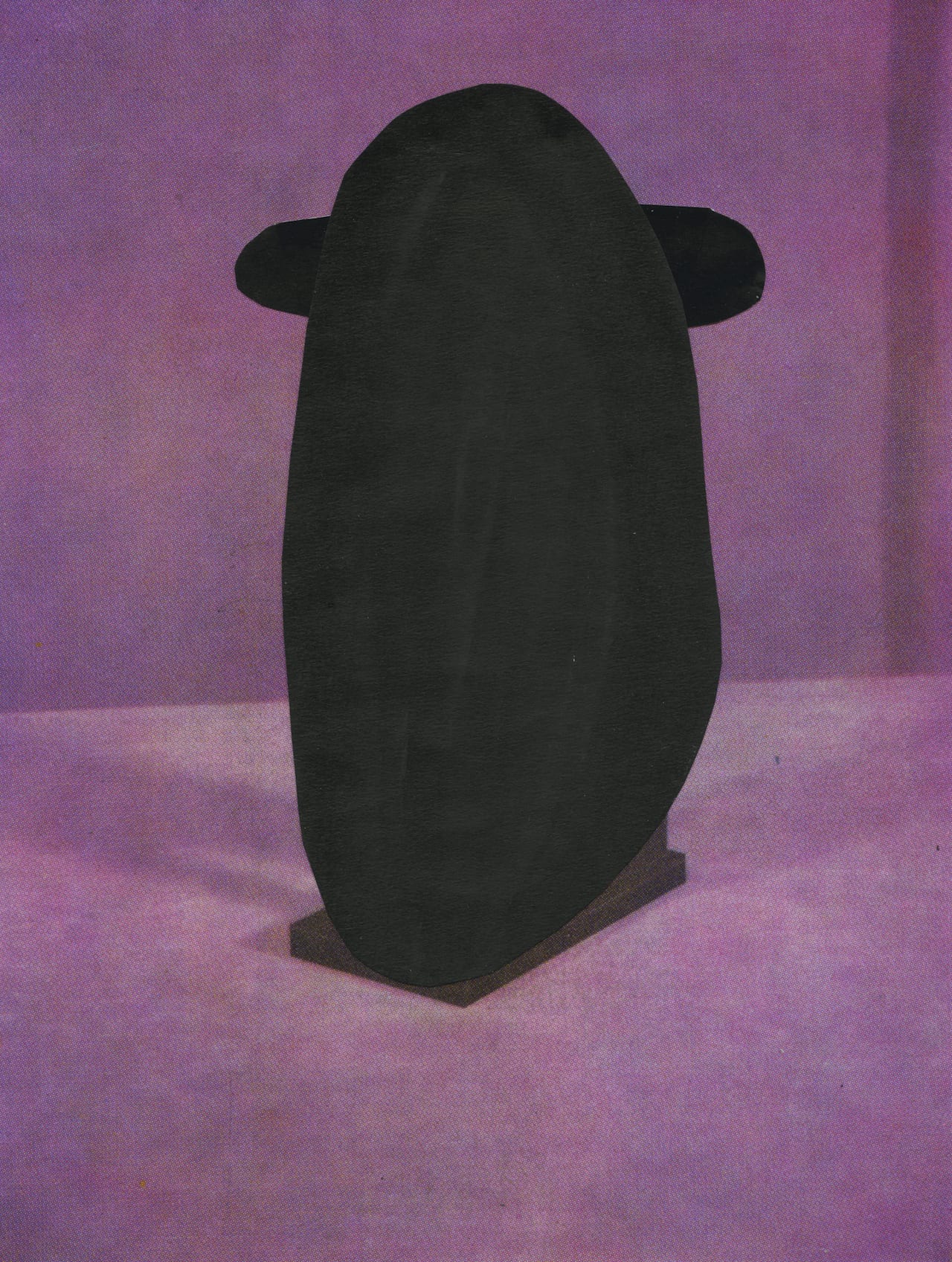

“I’m reclaiming my blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other,” says South African photographer Zanele Muholi. Born in 1972 in Umlazi, a township close to Durban, Muholi defines herself as a visual activist using photography to articulate contemporary identity politics. In her latest series, Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness, she uses her body to confront the politics of race and representation, questioning the way the black body is shown and perceived.